Born in the late 1470s, it did not take long for Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco to make his name in Venice. He soon rose to prominence as one of the city’s great talents, making it even more strange that he left behind so few works: there are only six paintings that are indisputably attributed to him. Nonetheless, his artistic legacy was immense and would go on to influence the later paintings of the Italian – and arguably the European – Renaissance.

10. Giorgione’s formative years followed the same pattern as many of his peers

The magnetic pull of Venice brought Giorgio to the city from his hometown of Castelfranco at a young age. Separate sources record that he took up an apprenticeship under Giovanni Bellini, in whose studio he is likely to have associated closely with many other successful and aspiring artists.

Although details about Giorgio’s youth are hazy, it seems that he quickly established himself as a unique talent and began producing works under his own name, the augmentative ‘Giorgione’, or ‘big Giorgio’.

9. Surprisingly, little of Giorgione’s surviving work is dedicated to religious themes

Like most of Italy, Venice was (and is!) filled with churches, and yet it is doubtful whether any of them were ever touched by Giorgione’s brush. In 1504, he painted the altarpiece of the Matteo Costanzo cathedral in Castelfranco, and he is recorded to have made miniature Madonnas, but little other religious work survives.

In fact, one could argue that Giorgione was among the first to create ‘art for art’s sake’, a motto that would only find its place in mainstream art several centuries later. His paintings often denied the viewer the moral, message or story they were so accustomed to seeking, and instead evoked feeling and atmosphere through their use of shape, color and subject matter. For instance, Giorgione has been credited with painting the first landscape in the history of Western painting, The Tempest. Of course, it is possible to find meaning and symbolism in any art, but Giorgione’s natural vista takes a step away from the moralistic, religious work of his contemporaries.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterSince the Church was generally better than private owners at preserving and recording its paintings, this might explain why so little of Giorgione’s work was recorded for posterity: the domestic paintings he did on private commissions are likely to have been lost or destroyed.

8. Giorgione worked at the forefront of the latest Renaissance development in portraiture

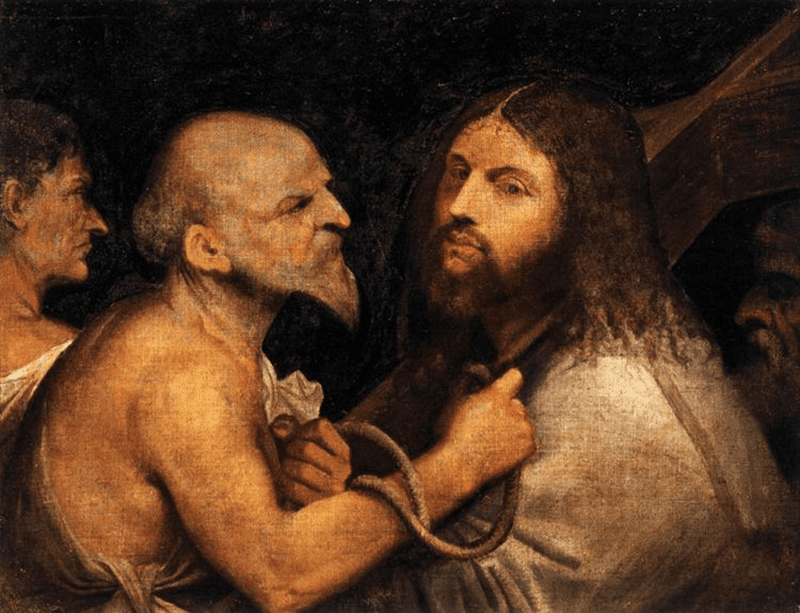

Along with his close associate, Titian, Giorgione transformed the genre of the portrait. His models no longer bear the serene, passive faces of former portraits. Rather, Giorgione strives to convey the emotion and personality of his subjects, some of whom stare directly at the viewer.

These are characters with whom we can interact, their expressions anxious, mocking, or in the case of Laura, defiant. The painting of the young girl bridges the gap between dignity and shame: her face proud and sophisticated, but her body exposed. Giorgione’s portrait work was so successful that at only 23, he was asked to paint the Doge of Venice.

7. His sensual touch led him to paint some revolutionary pieces

As well as kickstarting the genres of landscape and modern portrait, Giorgione was responsible for the first reclining nude in Western painting. His Sleeping Venus shows the goddess sleeping naked on a hillside, her sumptuous body mirroring the undulating landscape. It evokes the erotic ideal promoted by classical literature of the vulnerable woman in a magical pastoral setting.

Although such a bold subject was shocking at this time and place, it became a prominent motif in Venetian painting, and soon afterward, Titan produced his own, remarkably similar, Venus d’Urbino.

6. His close association with Titian has led art historians to debate the authorship of some paintings

The similarities between Titian and Giorgione are no coincidence, since they were both apprentices of Bellini, working together as assistants on a number of projects. They even appear to have collaborated on a number of later works: Titian is thought to have created the landscape of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, and to have completed several other paintings after his colleague’s death.

One-piece, in particular, the Portrait of a Venetian Gentleman, continues to provoke fierce debate between art historians, as they argue over its attribution. Some see Giorgione’s hand in the daring face of the young man, while others are convinced that it bears the characteristic marks of a Titian.

5. Giorione’s environment undoubtedly shaped his work, not least in his portrayal of women

The city of Venice was unlike any other in Italy, its proximity to the water made it a central trading hub that connected the west with the exotic lands of the east. This gave its artist early access to the rich new colors imported from abroad, and also exposed them to different cultures and appearances that often find a way into their work.

Nonetheless, it was still a strictly religious city with great regard for propriety and reputation, so much so that noblewomen were expected to maintain the utmost standards of modesty, rarely appearing in public. To compensate for this, Venice was famed for its escorts, prostitutes and courtesans. It is generally thought that these were the women used by Venetian artists as models for their paintings, especially nudes. It would be rare to find the same breed of passionate, sensual women seen in Giorgione’s work elsewhere in Europe at the time.

4. Certain pieces suggest that Giorgione may have been a keen astronomer

The new knowledge and understanding that was being developed during the Renaissance sparked increased interest in the field of astronomy, as scientists and philosophers alike looked to the heavens to unveil the universe’s secrets. Giorgione also lived at the dawn of the Age of Exploration, when European ships were being launched further and further afield to uncover exotic riches, using stars as an important means of navigation.

In fact, there is evidence that Giorgione may have helped to advance the science that accompanied these technical expansions. There survive a collection of drawings entitled Astronomy, which include an armillary sphere and diagrams of solar and lunar eclipses. Furthermore, the astronomer Aristarchus of Samos appears in his painting, The Three Philosophers. More importantly, however, the sheet of paper held by Aristarchus shows the four largest moons of Jupiter, a century before Galileo is claimed to have discovered them.

3. He certainly shared the contemporary enthusiasm for the classics

The paintings of the High Renaissance often depict the stories and myths of the classical world, replete with naked nymphs, majestic heroes and idyllic landscapes. Simultaneously, the work of Leonardo da Vinci meant that artists began to create human bodies with greater skill and accuracy, reflecting the sculptures of the ancient world. These features come together in Giorgione’s work, as he couples classical imagery with the rediscovered physical forms.

2. As with his youth, any information about Giorgione’s old age remains speculative

Information about Giorgione’s life and death must be inferred from a number of sources. In the Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari implies that Giorgione died during the plague while still in his mid-30s. This is supported by a recently uncovered archival document that records his death on the island of Lazzareto Nuovo, where Venetian plague victims were quarantined.

There is also a letter written by a noblewoman in 1510 requesting that her friend buy her a painting of the late Giorgione, with the reply asserting that the piece could not be brought for any price, suggesting the artist’s momentous popularity. And yet an inventory of inheritance records that the artist left behind little other than his paintings and his reputation.

1. Despite the lack of extant work, Giorgione proved to be one of the Renaissance’s greatest influences

After his premature death, Giorgione’s work continued to influence other artists for centuries. Titian developed his legacy, and together they are considered the founders of the Venetian School of painting. This movement was characterized by its passionate colors, emotional intensity and luxurious depth, as well as its radical approach to the subject matter, incorporating new secular models alongside traditional Biblical scenes.

Giorgione was immediately hailed as one of the greatest Italian artists of the age, and his revolutionary approaches to a painting made him a permanent figure in the canon of art history, continuing to inspire right up until the Romanticism of the early 19th century.