The African mask-making tradition has existed for centuries and is shared by many cultures on the continent. However, we do not know enough about it due to the absence of written sources. These masks represent ancestors’ spirits and deities that are invoked to oversee initiation rituals or bring success to the community. Read on to learn more about African masks, their meanings, and their functions.

African Masks and Their Origins: Mask-Making as a Cultural Practice

Masks have had many functions and meanings throughout history. Some cultures, like the Greeks, used them for theater, while others kept them as signifiers of benevolent spirits’ presence. Some, like Ancient Egyptians, used masks to cover the faces of their dead so they would retain their facial features in the afterlife. Regardless of a practical function, a mask always signifies the transformation of a person wearing it. A mask hides its wearer’s old identity and gives them a new one, transforming them into a spirit or a deity, or, like in the case of Egyptian burials, indicates their change of status.

During a ritualistic performance that involves the use of masks, the mask wearer sets aside their own identity and assumes one of a deity, a spirit, or another supernatural being their mask represents. Temporarily, their body becomes a vessel for the spirit, transforming the way the person usually moves and behaves. In many African cultures, ritual masks are used in initiation rituals that accompany a person’s transition from childhood to adulthood, marriage, or other transformative processes. They are also present in rituals related to harvesting and hunting.

The Western notion of art differs widely from that of other cultures, and for that reason, forms of art traditional to Africa were for a long time underresearched or even dismissed as curiosities. Fortunately, in recent decades the situation transformed, and today African masks are studied and presented not only by foreigners but by native African curators as well.

Preserving Stories and Beliefs: Masks’ Practical Function

Every sixty years, the Dogon people in West Africa perform the ritual commemorating the death of their first ancestors. For the ceremony, masters carve long masks representing the ancestor who was reincarnated as a snake. Curiously, this type of mask is not supposed to be worn and is simply carried around during the ritual. Other African cultures have similar ways of commemorating their ancestors through masks, like the Bambara, who see an antelope-like water spirit as their ancestor who taught humans to work in the fields. In that sense, such masks serve not only as ritual objects but also as instruments of protecting the culture’s mythology and history.

Unfortunately, our knowledge of the practical and ritualistic function of these masks, as well as the mythological connotations they bore, is severely limited by the lack of written or otherwise materially preserved sources. Another issue is the longevity of the material and the practical use of these masks. Most African masks were made from materials like wood or straw and naturally disintegrated during their practical use. Some stories were lost because there was no one left to tell them, as cultures either died off as the result of colonization and wars, and some assimilated into urban communities that distanced themselves from their traditional practices.

Partially, they mesmerize us exactly because we do not know enough about them. Concealed meanings and secret rituals are appealing to the human mind, which aims to reveal the secret and to stay enchanted by it for as long as possible.

What Do African Masks Look Like?

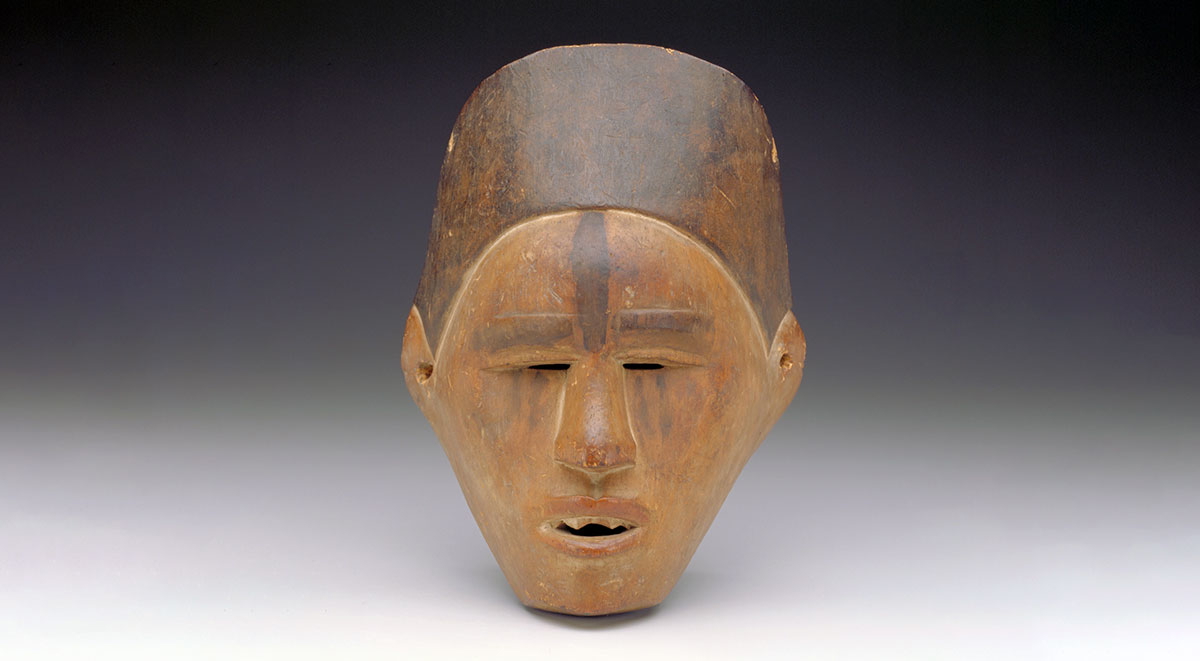

Although Westerners are used to perceiving these objects as a broad category of African art, the masks have major cultural and regional differences. African art experts can rather easily distinguish the culture in which a mask was created by looking at its proportions, ornaments, facial features (or lack thereof), decorative elements, and materials. Not all regions of the continent preserved their traditions of mask-making. Today, the majority of discovered and researched objects are attributed to West and equatorial Africa.

Although the concept of masks is in our mind mostly associated with an object covering one’s face, African masks are often more complex. Some of them also cover the wearer’s neck or shoulders, or exist simply as headdresses, leaving the face uncovered. African masks usually represent beings that look similar to humans (men, women, or even androgynous figures), or various animals that are significant to the culture of their creation. In many cases, masks represent the spirit of ancestors watching over their people and participating in their rituals. Despite the gender diversity of deities and spirits, in most cultures, mask wearers are exclusively male. Women can create masks and participate in rituals, but they rarely put them on. The only exception encountered by researchers was a women’s initiation society in Sierra Leone that performed initiation rituals for girls using masks both made and worn by women.

African masks are always stylized but rarely abstract. However, masks made in Dogon and Igbo cultures are usually the furthest removed from realistic depiction. Dogon masks frequently feature abstract geometric designs. Art historians attribute this fact to the spread of the Islamic faith on the territory of Mali, where the Dogon population is most prominent. Instead of suppressing local beliefs and practices, Islam blended in with them, incorporating the tradition of non-figurative painting into traditional Dogon art.

Masks with human faces often represent ideal genderly marked beauty. For instance, wooden masks of feminine deities carved by the Yombe people prevalent in Congo and Zambia often have distinctive carefully filed teeth that signify health and beauty. In other cultures, researchers indicated long necks, scars, or thin noses and beauty ideals found represented in masks. Feminine figures representing ideal beauty usually are invoked to bring fertility and good harvest.

African Masks & Modern Western Art

African art established its presence in Europe during the late 19th century when most of the continent was conquered and colonized by the Western powers and divided into zones of influence. Present-day political maps of the African continent are mostly based on these former zones rather than on actual ethnic, cultural, or social distinction, thus the artificially installed borders present a challenge for local museums and historians.

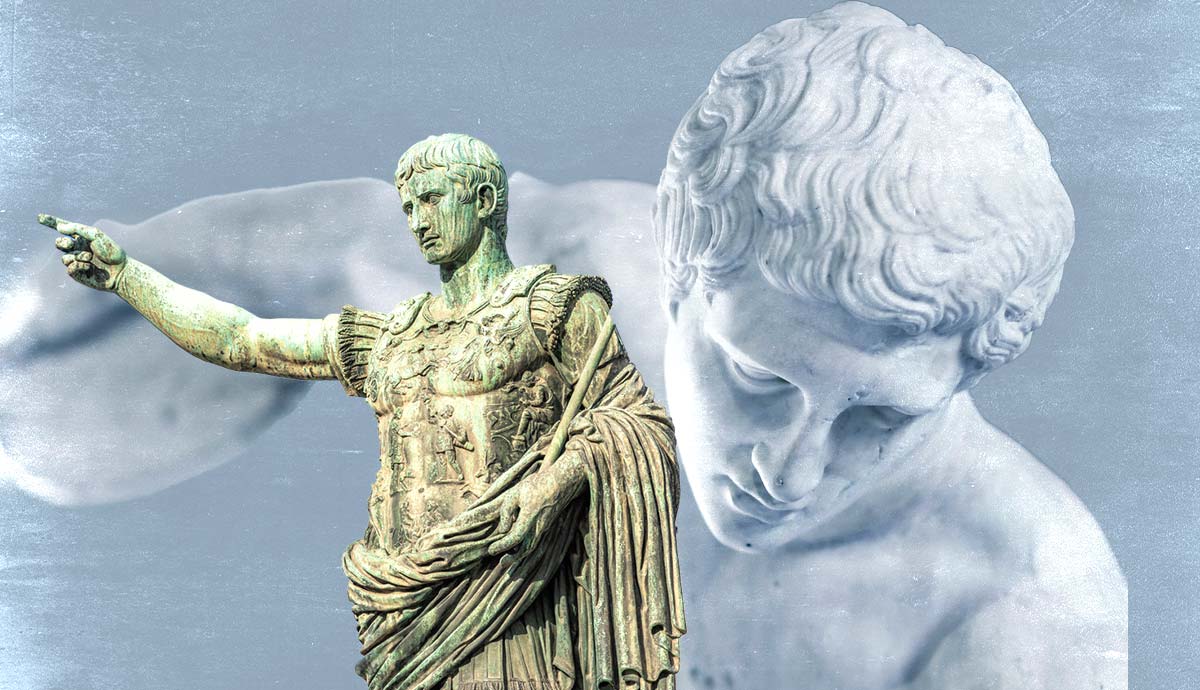

African masks, sculptures, and other objects that ended up in Western collections had different backstories. Some of them were legally purchased from their creators and owners, while others were looted from the places of their origin. At the time, very few art collectors were interested in them, and the majority of the public treated the masks simply as curiosities produced by “primitive” people for their ceremonies. In other words, the research on these objects was limited to a reductive anthropological point of view. However, there were rare exceptions who saw them as aesthetic alternatives to the Western visual canon. Among these exceptions was Pablo Picasso, the artist who invented Cubism by relying on the expressive use of line and form in African art.

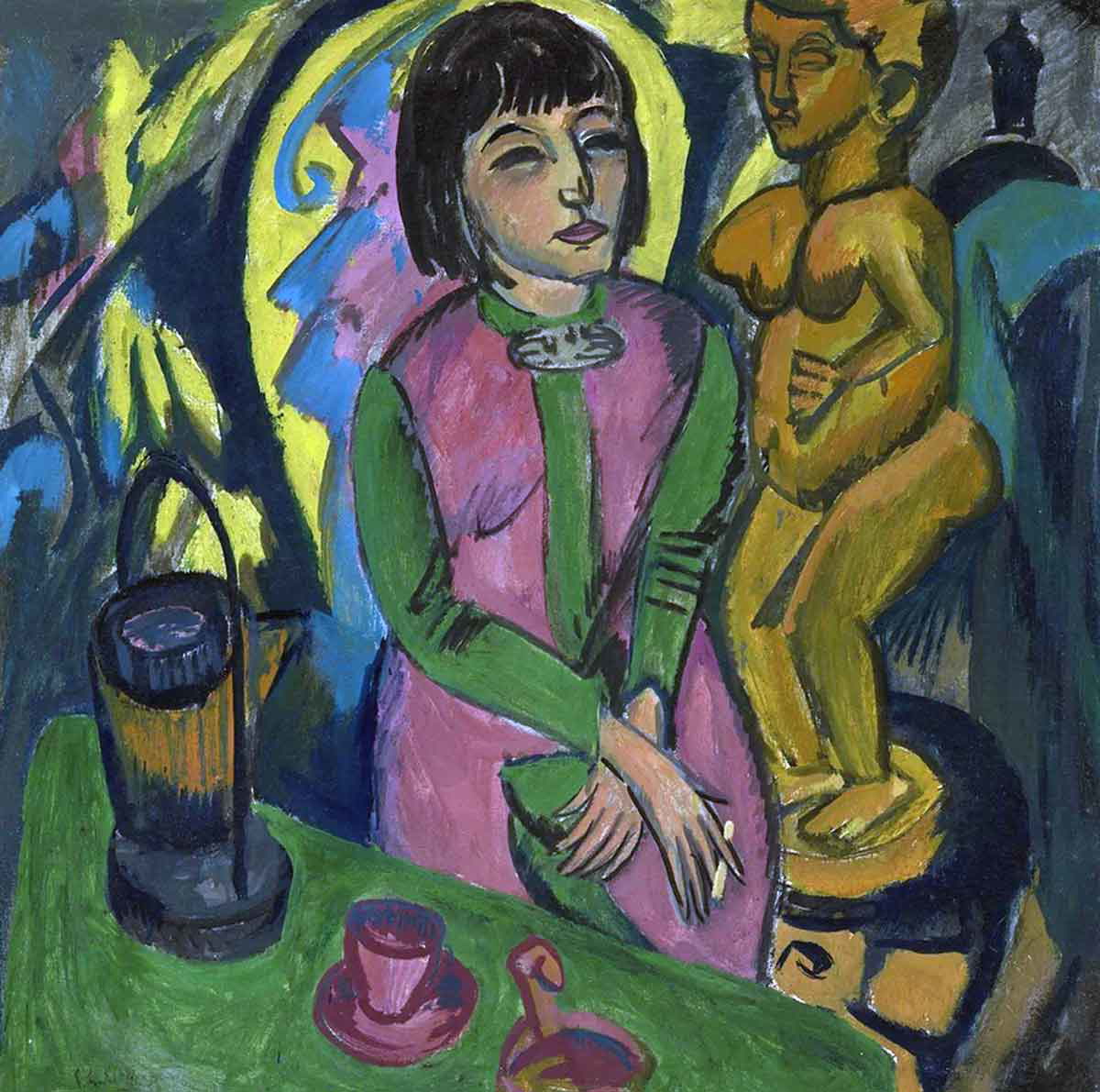

Another art movement that borrowed a lot from African art was Expressionism. Launched in Northern Europe in the early years of the 20th century, it prioritized subjective artistic expression over the objective experience of reality. Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde found in African sculptures the raw and direct emotional force that allowed them to put more expressive power into their works.

Preserving African Masks: Ethical and Technical Issues

In a generalized understanding of African art, the masks are usually carved from wood. However, wood is not the only available material. African masters from various cultures use clay, straw, shells, natural pigments, animal parts like horns, teeth, bones, cloth, and other materials available in their region. However, natural materials are hard to preserve, thus most of the masks in private and museum collections are younger than 150 years.

An exception from that rule applies to the famous Benin masks made from ivory and bronze, which date up to the sixteenth century. These objects became known not only for their long history, but also because of the 1897 Benin Expedition of the British forces, during which many Benin civilians were killed, and the royal palace was looted. The stolen artifacts ended up in the collections of various museums in the West. In the recent decade, many Benin artifacts were restituted and they now belong to Nigerian museums.

However, the act of restitution on its own does not end the ethical issues around the masks’ display in museums. Unlike many traditional works of art that were created to be admired by the public, these masks had a practical function for those who created them. They acted as stand-ins for their ancestors and deities and assisted them in their routines. In some cultures, ritual masks are disposable, and thus are burned or otherwise destroyed immediately after a ritual. Others were used for years and, after their destruction, received proper human-like burial. In this context, their preservation in museums goes directly against their intended function, making them unavailable and useless for those who created them.