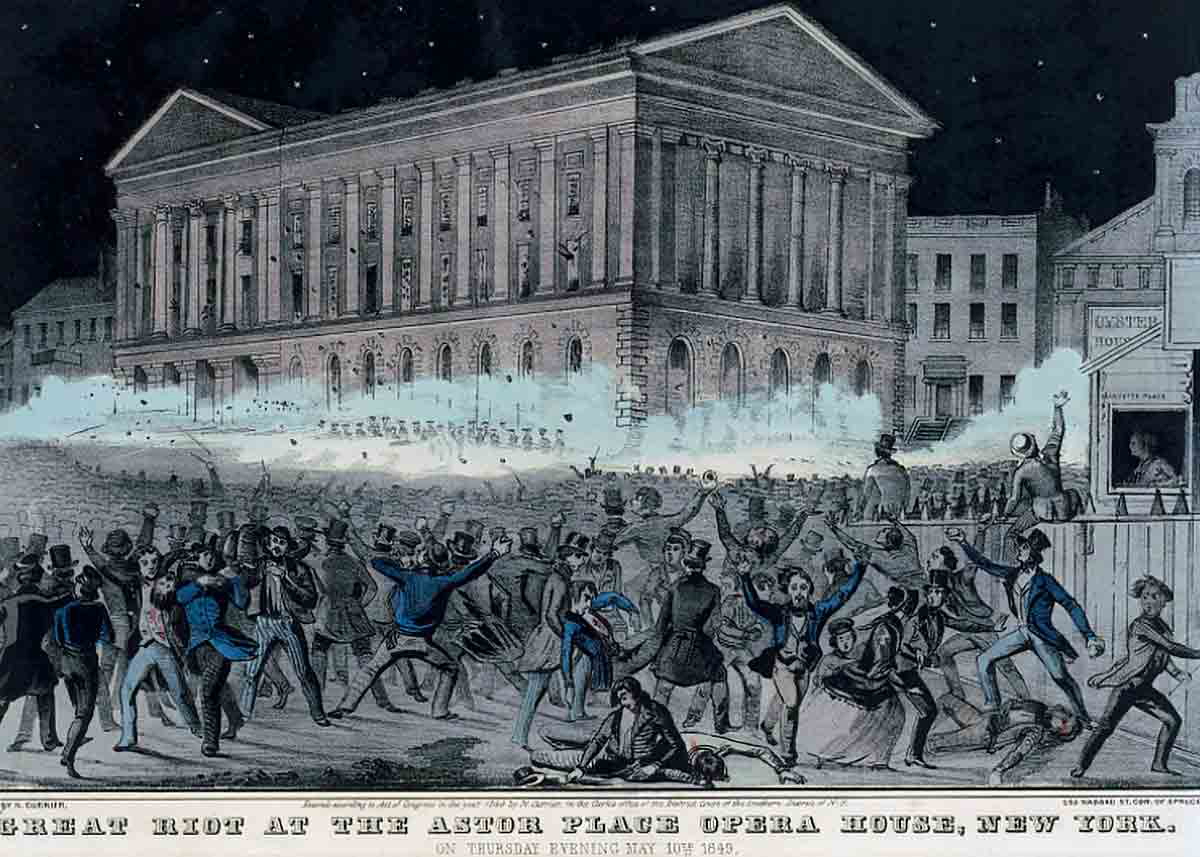

In antebellum New York City, a rivalry between Shakespearean stage actors spiraled out of control. Supporters of the actors violently clashed in the streets in front of the Astor Place Opera House in May 1849, leading to nearly two dozen dead, 150 wounded, and 177 arrested. How do we make sense of this event? Did people really die in defense of an actor’s reputation? Let’s explore the Astor Place Riot, which was less about artistic differences and more about class tensions.

The Actors: Who Was William Macready?

William Charles Macready was one of the most famous actors of his age. An Englishman, he grew famous across the pond as well, first touring American cities in 1826. He hadn’t always wanted to be an actor—he considered the law first—but grudgingly began performing with his father’s theater company and debuted as Romeo in 1810. As the years passed, he garnered more popularity and became well-known for his Shakespearean roles, including Hamlet, King Lear, Richard II, and Iago.

It was Macready who helped restore the full text of King Lear to the stage. Beginning in 1681, when Nahum Tate created an adaptation of the play, the Fool had always been omitted and the characters given a happy ending, with both Lear and Cordelia living. Macready did not think he could be true to the character of Lear in this truncated, altered version, and he brought the full text back. The Theatrical Examiner enthused, “We never saw any tragedy, in so far as we could judge, affect an audience more deeply than the manner of the whole management of this tragedy of Lear. It was indeed a triumph for the stage.”

Macready was known as a “traditional” actor. His delivery was measured, grand. The poet Robert Browning, with whom Macready corresponded, said Macready was “one of the most admirable and indeed fascinating characters I have ever known: somewhat too sensitive for his own happiness, and much too impulsive for invariable consistency with his nobler moods.”

Rival: Who Was Edwin Forrest?

American Edwin Forrest was the workingman’s actor. In his impassioned portrayals of frontiersmen and Native Americans, he elicited ardor and loyalty from lower-class theatergoers. He also played notable Shakespearean leads such as Macbeth, Hamlet, and King Lear.

Forrest was born in Philadelphia in 1806 and began acting in the 1820s, attaining fame for his portrayal of Othello in New York City. He was a political figure, of sorts, and even delivered the keynote speech at the 1838 Democratic convention in place of the actual President of the United States, Martin Van Buren. In particular, Irish immigrants saw him as the embodiment of their working-class values.

He disliked the British theater scene, considering it elitist and insular, and eschewed the mannered, intellectual style of English actors. Forrest’s biographer claimed “no one carried the democratic fever to the stage with such fierce passion,” and his supporters heralded his “vital, burly Americanism.” Though he loved Shakespeare, he thought it important to bring attention to American playwrights and their works, holding a yearly contest for original plays about Americans. One of the winners was Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags, in which he played the lead role not long before the Astor Place Riot.

Setting the Stage: The Astor Place Opera House

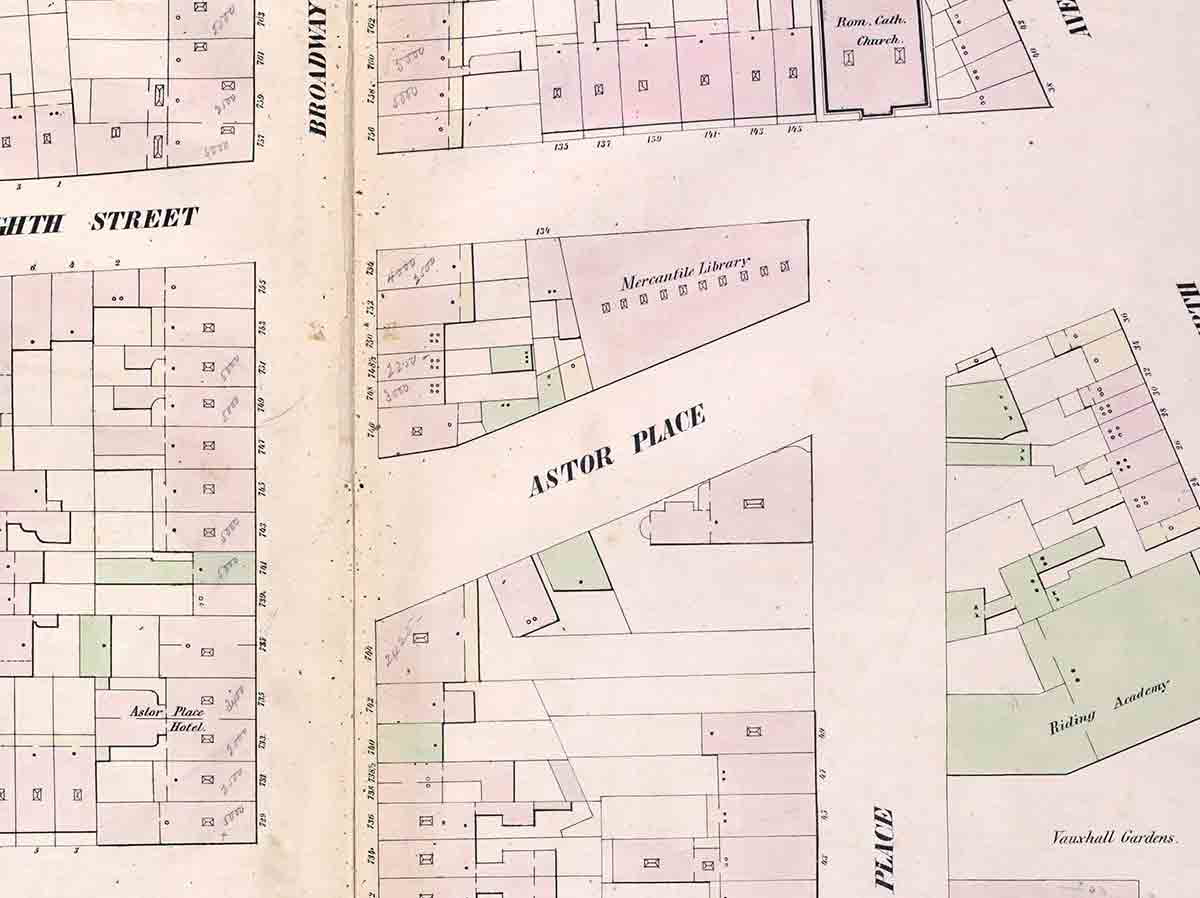

The location of the Astor Opera House is one of the biggest reasons the riot turned as deadly as it did. The neighborhood was crossed by two thoroughfares, Broadway and the Bowery, that abutted and met at the Opera House. While both were populated with theaters, halls, taverns, and various other amusements, Broadway was seen as catering to the upper classes and the Bowery to the lower.

The Opera House was built in 1847 and was clearly intended to bring in more decorous, elite audiences. It was imperious in its appearance, and the seats were comfortable and luxurious. There was a dress code, and the seats were arranged in a way that made opera-goers’ dress conspicuous. The New-York Tribune explained that “opera must have an elegant environment if it is to succeed,” and another cultural critic lauded it as “one of the most attractive theatres ever erected.”

Unsurprisingly, there were also some criticisms of the opera house and its snootiness. Godey’s Magazine and Lady’s Book sniffed, “The monopoly of the best seats by certain subscribers and stockholders of the Astor Place Opera House, has been the great objection and great drawback to that establishment. To the masses of the rest of the community, it has an appearance of exclusiveness and monopoly which will not be tolerated by them.”

A Rivalry Turns Violent

Throughout the late 1830s and 1840s, Macready and Forrest developed a rivalry that spread to, and was exacerbated by, their fervid supporters. When Forrest visited London in 1845 to play Macbeth, a cool reception led him to assume that Macready had besmirched his reputation, so Forrest “hissed” at Macready from the audience while the older actor was on stage playing Hamlet. They took their growing animosity to the press, which gleefully printed and reprinted their harangues.

By 1848, Macready was preparing to retire and decided to embark on a farewell tour in the United States. Unfortunately, it seemed like all anyone wanted to talk about was his feud with Forrest, which was wearying to the actor.

Macready kicked off his farewell tour at the Astor Place Opera House on October 4th, 1848. It went well, and he continued the tour in other American cities. Occasionally, he was met by taunting Forrest supporters, though, and he could not resist sniping back at Forrest, one time referring to him just as an “actor” and not calling him by name. The New York Herald said they “resemble[d] two children.”

Macready decided his last engagement would be at the Opera House in New York, where he would play Macbeth. Forrest was not far away, in residence at the Broadway Theatre, also playing Macbeth. When Macready took the stage, he was met with a cavalcade of criticism, as people hissed, booed, and threw things onstage. At one point, someone threw a chair from the second tier, which landed in the orchestra, and then three more were thrown. Macready exited the stage, and the Tribune deemed the night a “disgraceful row.”

Macready decided not to return to the Opera House the next night, but Forrest went on as scheduled, playing the role Macready was supposed to have performed. Forrest then staged Metamora while the Opera House hosted The Merry Wives of Windsor without Macready. Elite New Yorkers signed a petition begging Macready to return and promised no trouble, so he agreed to return for Macbeth.

The petition from the elites was picked up by the newspapers and was seen as a further affront to the Forrest supporters. The new mayor, Caleb S. Woodhull, planned to attend Macready’s final bow and requested a police presence. Unfortunately, the Chief of Police said his force was not large enough to ensure containment of a serious riot, so Woodhull then asked a regiment of the State’s militia to be stationed at Washington Square Park. The stage—literally—was set for a clash.

Historian Fran Leadon provides some of the larger context: “Two famous, aggrieved actors arguing—so what? But it mattered very much that Forrest was American and Macready was British, at a moment when British-American relations were at a low point…Siding with Forrest became a populist badge, even if hatred of Macready and his supposedly pro-British, elitist fans had forged an unlikely (and temporary) alliance between Nativists and the Irish immigrants they despised. Everyone was on edge anyway, as the Macready-Forrest rivalry played out against a backdrop of social unrest that had begun the previous year with revolutions sweeping across Europe.”

Street Brawl: The Astor Place Riot

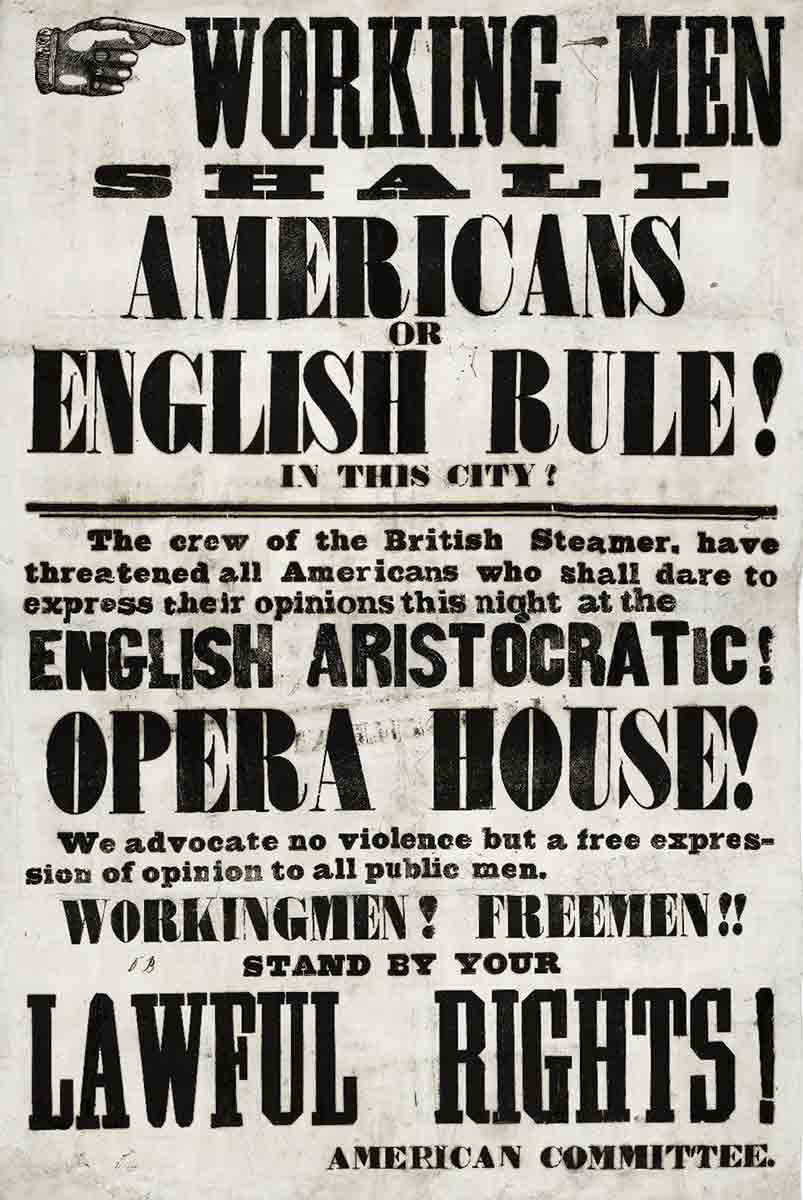

Forrest’s supporters bought tickets and distributed an inflammatory handbill throughout the city that deemed the Astor Opera House an “English aristocratic” space and urged “Workingmen” and “Freemen” to “stand by your lawful rights!” Many of them entered the theater, where they proceeded to heckle and boo Macready. Police stationed inside arrested some, and the apprehended attendees remained inside until the morning.

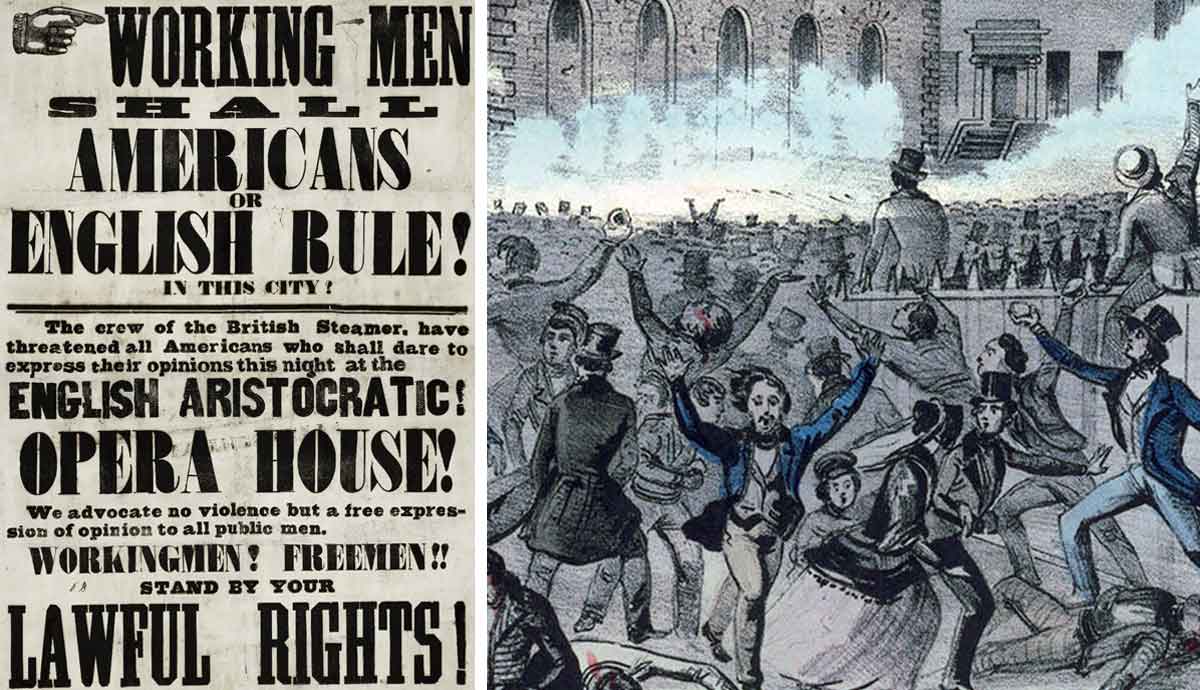

Outside, though, the crowd, which grew to 10,000, began assaulting the building, and Major General Charles W. Sandford of the militia realized he did not have enough manpower to control them. The gas lamps were doused by rioters, the crowd surged, and the troops, who had been forced onto the sidewalk in front of the theater, were struck with stones and other projectiles. Sandford ordered his troops to use fixed bayonets, but the crowd tried to yank them away. Many onlookers were in the triangular space in front of the Opera House, and as soon as the troops began firing on the crowd, they began running in terror. (Macready, it’s noted, finished his performance and snuck out the back, blending into the crowd and departing before the carnage broke out.)

One bystander who managed to escape explained to the press, “I don’t know how long I stood there, I was so frightened…I stood there until I heard another banging of muskets, and then I started and ran home as quick as I could; I should not have gone there, if I had known they were going to use lead; I went to see what was going on, like many others.” Historian Fran Leadon writes that the real tragedy of the riot was that “almost all of the people killed were bystanders” and seven were under 21 years of age.

Aftermath: Lessons Learned?

After the riot dissipated, the extent of the violence was clear: 18 died in the riot while four additional victims died by the end of the week, and 150 were injured. There was a mass rally at City Hall the next day, but when people made their way up to Astor Place, the militia again threatened them with muskets, and they dispersed. The elites of the city went back to business as usual almost right away.

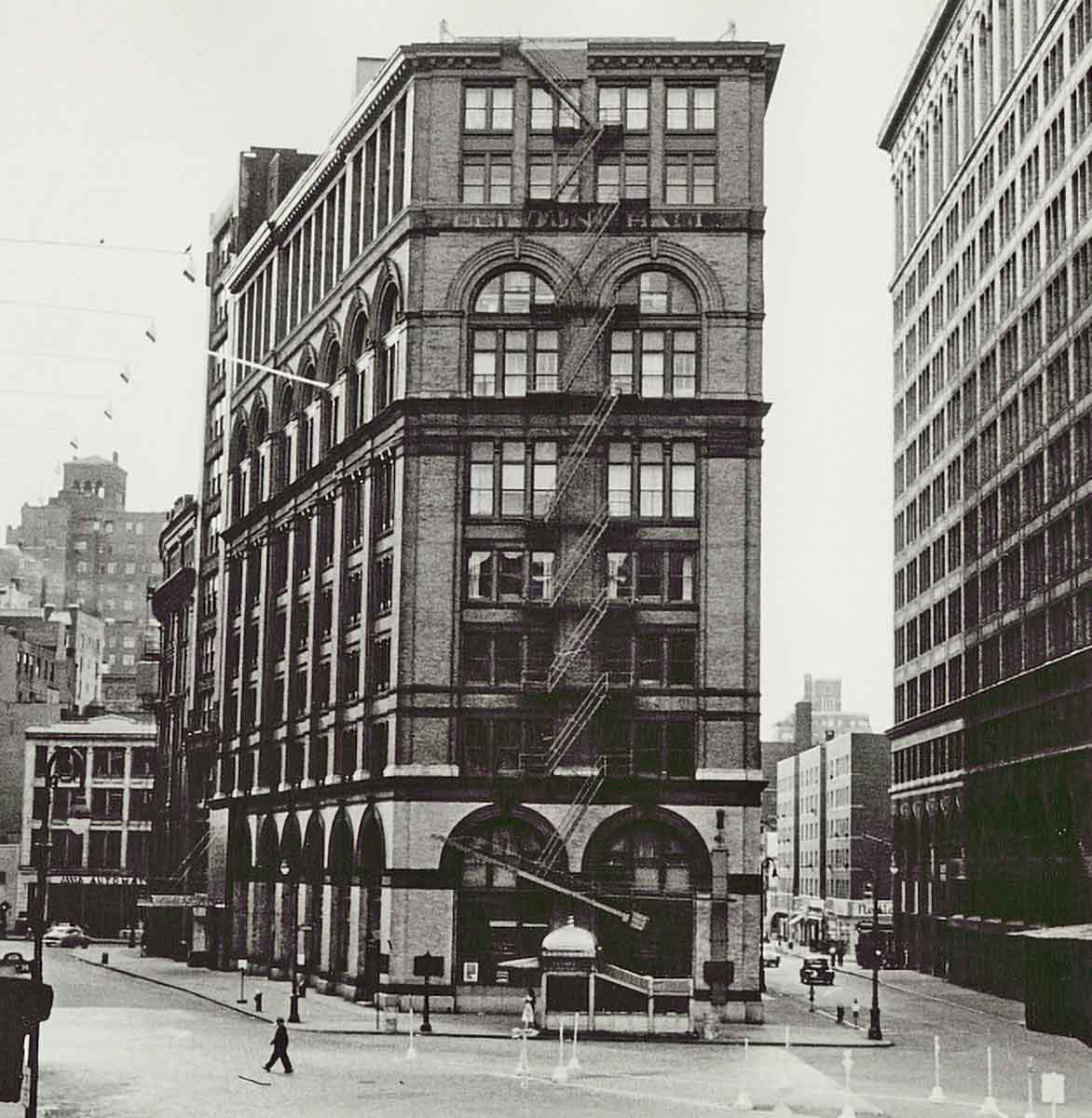

The opera house was not destroyed, but the walls and doors were heavily battered, the windows broken. It received the nickname “Massacre Opera House.” The Academy of Music near Union Square soon replaced it as the elites’ preferred theater. The interior of Astor Place was broken down and sold off, and the building’s shell was sold in 1853 to the New York Mercantile Library for $140,000. They renamed it Clinton Hall, but it was torn down in 1890 in favor of a larger building, which currently stands on the site.

The actors whose rivalry spurred this tragedy largely avoided any sort of blame for the event. Macready went home and Forrest continued to triumphantly take the stage.

Historian Leo Hershkowitz concludes somewhat ruefully about the riot, “For society at large, issues of political division, class antagonism, bigotry, police power, law and order, the prime issue of defining the rules and delineating the bounds of democratic freedom of expression in the face of terrorism, remained to be resolved perhaps at some future time.”