Hercules, Perseus, Theseus, Odysseus – we know all these names well. However, it’s time for Atalanta to take the stage. Despite being abandoned as a baby in the wilderness by a father who wanted a son, Atalanta survived and grew up to become a fierce and renowned huntress. Atalanta’s mythology shows that you can take the woman out of the wild, but you can’t take the wild out of the woman.

Atalanta’s Mythology

Just like many of her fellow heroes, Atalanta’s story had a striking beginning. Her father wanted sons and when Atalanta was evidently not a boy at birth, her father ordered her to be exposed.

In Ancient Greece, infant exposure was, troublingly, not uncommon. There was a cultural acceptance that parents could leave an unwanted child in the wilderness, as they could be picked up by a stranger who wanted a child. This way, adults could absolve themselves of guilt for potentially leaving the child to die since there was a possibility that someone else would adopt the child. However, children were not always rescued.

Atalanta was abandoned near a cave and deep within a forest. The story goes that she was found by a she-bear and suckled as the bear’s own. In many interpretations, the bear was seen as Artemis’ blessing for her.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

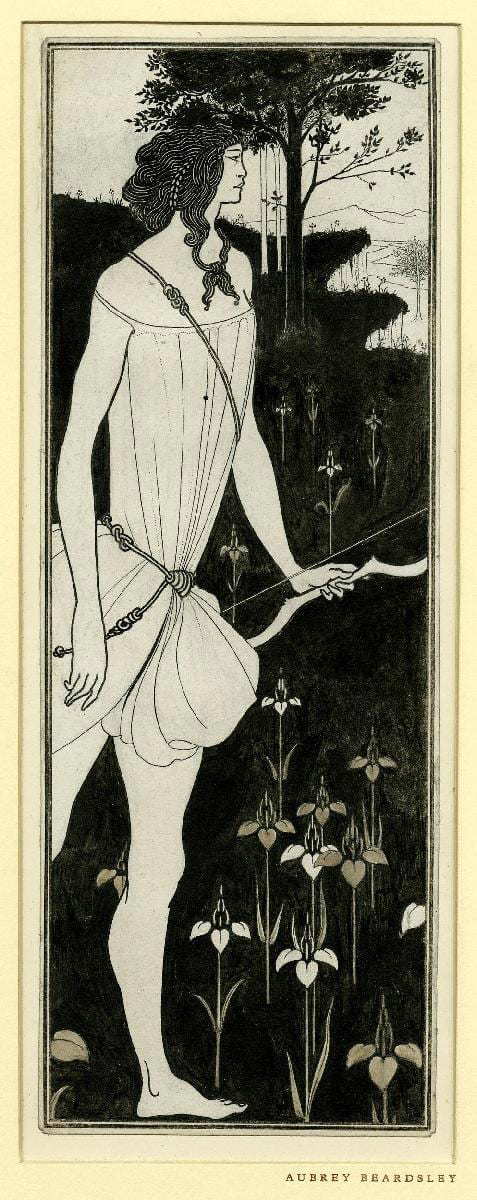

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterIn Ancient Greek religion, Artemis was the Olympian Goddess of the Hunt, Wild Animals, and Chastity. Artemis became Atalanta’s idol. In keeping with the goddess’ example, Atalanta rejected the company of men, just like the maiden goddess, and honed her skill with the bow and arrow becoming an expert huntswoman.

Atalanta’s Harmony Invaded

Eventually, a group of hunters found Atalanta, took her back into society, and raised her until young adulthood. Aelian, a Roman author, records that she created a beautiful home in the forest for herself, teeming with bountiful wildlife. , describes Atalanta’s grove:

“At the bottom of the valley was a large and very deep cave […] Ivy encircled it, the ivy gently twined itself around trees and climbed up them. In the soft deep grass there crocuses grew, accompanied by hyacinths and flowers of many other colors, […] a feast for the eye; in fact their perfume filled the air around. In general, the atmosphere was of festival, and one could feast on the scent. There were many laurels, their evergreen leaves so agreeable to look at, and vines with very luxuriant clusters of grapes flourished in front of the cave as proof of Atalanta’s industry. … The spot was full of charm, and suggested the dwelling of a dignified and chaste maiden.”

Aelian Historical Miscellany, 13.1

In Atalanta’s mythology, it is recorded that she lived peacefully there until one day, two centaurs designed to force themselves on her. She sighted the two centaurs wreaking havoc armed with fire torches as they charged towards her home. Atalanta fearlessly took two arrows and shot them both down.

Atalanta the Swift of Foot Huntress

Atalanta became renowned throughout Greece for her hunting skills and also for her speed on foot. She gained the fitting titles along with the variation of “fleet of foot” and “most swift-footed among mortals.” Aelian writes that she was a rare sight to behold and that she did not often show her face among society. Instead, she preferred the solitude and freedom that nature could provide.

“To meet her was remarkable, especially since it happened rarely; no one would have easily spotted her. But unexpectedly and unforeseen she would appear, chasing a wild beast or fighting against one; darting like a star she flashed like lightning. Then she raced away, hidden by a wood or thicket or other mountain vegetation.”

Aelian, Historical Miscellany, 13.1

Atalanta and the Calydonian Hunt

Atalanta’s mythology is connected to other heroes too, as she was the only woman called to help hunt the fearsome Calydonian Boar.

In this story, the King of Calydonia, Oineus, had forgotten to include the goddess Artemis in the annual sacrifices that year. This provoked Artemis’ wrath who sent a boar of extraordinary strength and size to destroy the village.

King Oineus summoned the noblest men of Greece to help hunt the gigantic boar that was terrorizing Calydonia. Among these were: Jason, Theseus, Meleager (King Oineus’ son), Peleus (the father of Achilles), Castor, Polydeuces, and others.

Just before the hunt’s outset, some men refused to hunt alongside a woman and complained at Atalanta’s presence. Meleager, the King’s son and leader of the hunt, was angry at their discrimination against a woman and commanded them to join. Apollodorus, the Greek mythographer, writes that Meleager was attracted to Atalanta, so his defense on her behalf was in hopes of impressing her.

Nevertheless, the band set out on the hunt. In the encounter with the Calydonian Boar, a few men were struck down straight away and killed. In the crossfire, men were taking down each other, too.

In one version of Atalanta’s myth, written by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, Ancaeus declared a woman would not best him and dived in to attack the beast. In some versions, Ancaeus prayed for Artemis’ blessing on the attack. Still, she ignored his prayer, as clearly Atalanta was a favorite of Artemis and she did not appreciate the insult to one of her devotees. He soon was killed by the boar.

Nevertheless, Atalanta first shot the boar in the back, which meant that another hunter then managed to shoot it in the eye. Meleager delivered the final blow but gave the boar’s skin and head, the customary prize, to Atalanta for drawing the “first blood.”

The Calydonian Hunt: Aftermath

Atalanta was praised by many of the heroes, but some had grievances. The uncles of Meleager, who had been on the hunt, were angry that a woman should get the prize and honor instead of any one of the men. They argued that if Meleager did not want the prize, it should go to them due to their familial relationship. They stole the prizes from Atalanta, which was an insult to her honor. Angered again at the mistreatment of Atalanta, Meleager killed his uncles in a fit of rage and returned the skin.

Ovid, in his Heroides, writes,

“Meleager took fire with love for Atalanta; she has the spoil of the wild beast as the pledge of his love.”

Unfortunately, before he could act on his demonstration of love, his mother, in grief at the murder of her brothers, magically attached Meleager’s life force to a branch and then set it alight. As the wood perished, so did Meleager.

Atalanta’s Adventures with the Argonauts

After this, Atalanta traveled widely with other heroes. One of the stories in her mythology is that she boarded the Argo ship, wanting to be part of the historic expedition. Landing on the deck, she invoked the protection of Artemis. Artemis represented celibate women, so none of the men could pursue Atalanta’s affections without her consent if they did not wish to face the goddess’s wrath.

So, Atalanta joined the crew for the Argonauts, with Jason as the leader, and helped him on his quest. She also took part in the celebratory games held by the Argonauts for Pelias. In these games, she wrestled with Peleus, the father of Achilles, and won.

It was very uncommon for a woman to be so involved in “men’s activities” during her time, but Atalanta continued to pursue activities of her own interest.

Atalanta in Greek mythology appeared to have such a fierce gaze that people often didn’t know if they feared or loved her. She had a commanding presence that she used to her advantage to fight against discriminatory efforts.

To marry or not to marry?

The time soon came when Atalanta’s father recognized and brought her back into his household. He desired that she should marry, but Atalanta was opposed to this. One Oracle had warned her that if she married, it would bring about her doom. Frightened by the ominous prophecy, Atalanta vowed never to marry.

In order to ensure that she would never have to marry, as her father put lots of pressure on her, she devised a plan. Atalanta set her own conditions: whoever was to become her husband must compete with her in a footrace and win. Since Atalanta was the swiftest on foot than any other person alive in her time, she was sure that she would never lose a race. Her terms were that if she caught up with the suitor, he would be sentenced to death. This was intended to be quite a deterrent. However, if the suitor beat her in the race, then she would marry the victor.

Many men were enthusiastic about attempting the challenge, but alas, each one was caught up and killed. The news of Atalanta’s deathly competition became mythical in its own time. A young prince, Hippomenes, heard of the challenge and the many fatalities, and according to Ovid’s version, wondered, “Why seek a wife at such a risk?” But upon meeting her himself, he soon fell in love with her and entered the competition.

Apple of My Eye: Hippomenes Competes for Atalanta

In Atalanta’s mythology, as recorded by Ovid, when Atalanta met Hippomenes, her gaze, once renowned for its piercing and hard stare, softened. She felt attracted to Hippomenes and so was upset that he would die. Atalanta truly was the swiftest of foot in Greece and would inevitably catch up to Hippomenes. By her conditions, she would have to kill him for his failure.

Hippomenes, desperate to win the race and marry Atalanta, prayed to the goddess Aphrodite for help. When she heard Hippomenes’ prayer, she took him aside and gave him three golden apples. She told Hippomenes that these apples were enchanted so that Atalanta would not be able to resist picking them up.

As the race began, Hippomenes tossed a golden apple, and true to the goddess’ word, the beauty of the apple was so irresistible that Atalanta could not help but stop to pick it up. Every time Atalanta stopped to pick up an apple, Hippomenes drew ahead.

The last apple, he threw way off course from the racetrack. Atalanta hesitated, but Aphrodite’s power was too great – she veered from the track. And this time, the final apple was enchanted to be very heavy, costing Atalanta even more time. Hippomenes passed the finish line, and Atalanta became his bride.

Atalanta and Hippomenes: Can You Feel the Love Tonight?

Sadly, Hippomenes’ luck ran out. Engrossed in ecstasy about his marriage to Atalanta, Hippomenes forgot to thank the goddess for her help. Aphrodite was angered at Hippomenes’ forgetfulness; in retaliation, she stimulated an uncontrollable passion in Hippomenes and Atalanta. They began to make love in a nearby temple. The temple was said to be either Zeus or Cybele’s, but regardless, the god or goddess was very offended and so transformed the couple into lions. A fitting form, as she was able to be as fearsome in her new transformation as in her human form.