Autogolpes, or self-coups, occur when a leader who came to power legitimately overthrows themselves as president in favor of an illegitimate but all-powerful leadership position unburdened by his country’s legislature or judiciary. While the best-known autogolpe in the Latin American region occurred in Peru in 1992, successful and attempted self-coups have plagued the region since independence. Is Latin America especially susceptible to autogolpes, and if so, why?

Latin America: Birthplace of the Autogolpe?

While various forms of government overthrow have abounded around the globe, the autogolpe, the name itself born in the region, seems to be especially prevalent in Latin America. The key to this phenomenon may lie in how independent governance evolved in the wake of colonization and the rise of caudillismo.

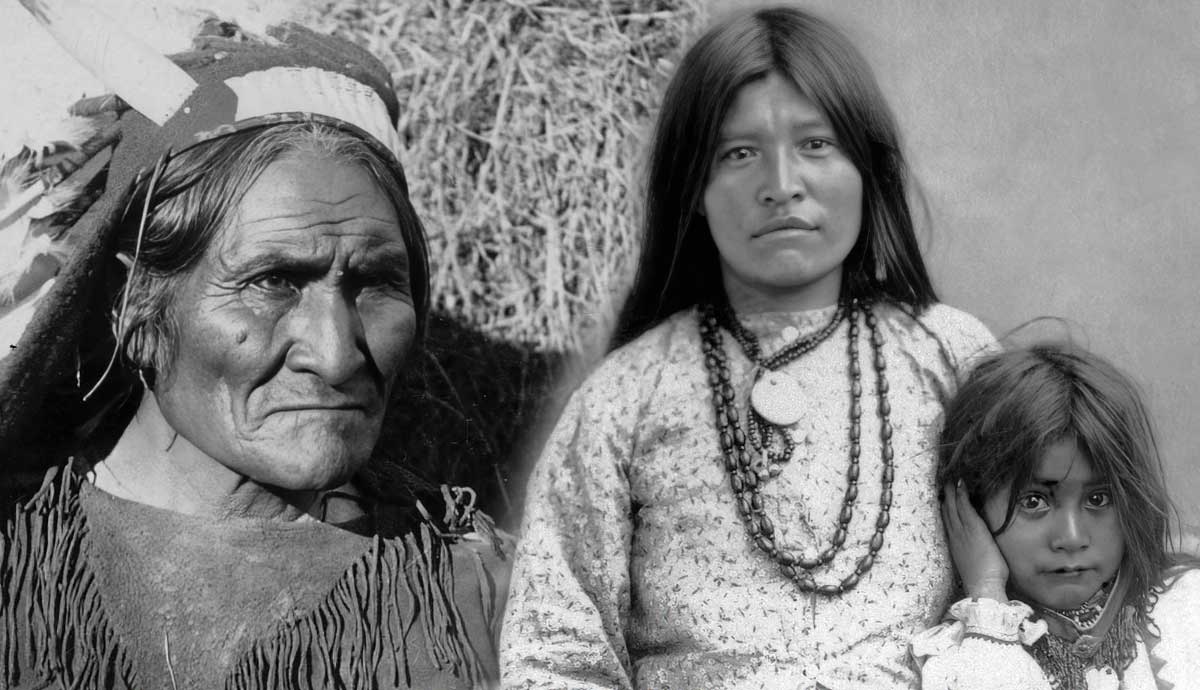

In the power vacuum left behind after Spain’s withdrawal from the continent, former military leaders often took charge, having gained influential wealth and power from the lands they were granted in reward for their service. In this period of instability, people looked to strong rulers who could protect them. These caudillos, steeped in military traditions of unquestioned authority and strict adherence to orders, led the only way they knew how: with an iron fist. Caudillos might pursue policies that were progressive or conservative, but their governance style was authoritarian.

While caudillismo ultimately fell out of favor with the global push toward participatory democracy, it had left its mark: a practice, both among politicians and the populace, of obedience to a single, strong-willed leader. This tradition was necessarily at odds with the multi-pronged structure of democratic governance, as well as the development of institutions to hold the government accountable. As a result, democracy was slow to take hold in Latin America, undermined by military coups, authoritarian power grabs, and outright dictatorship throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries.

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that when democracy did get a foothold, elected leaders struggled to function under a system designed to impede unilateral rule. While they believed in democracy enough to get themselves elected, such a belief often did not extend to their actual time in office. From here, then, the autogolpe is born.

Self-Coups Without a Name: Early Autogolpes

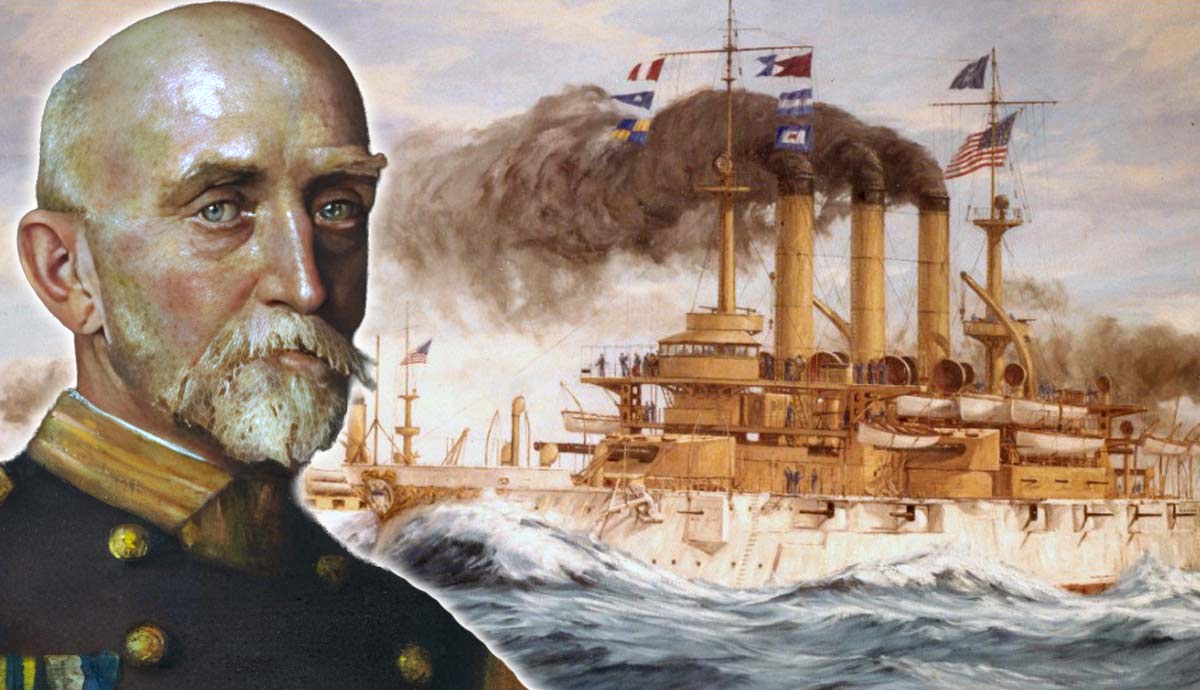

The term “autogolpe” did not enter the political discourse until, arguably, the late 20th century, and the majority of government overthrows in Latin America prior to that were orchestrated by the military, sometimes with the help of the CIA. Still, there are several historical events for which the term could be applied in retrospect. Mexico’s famous Santa Anna, for example, pursued a number of autogolpe-like tactics during his numerous presidencies, including the dissolution of congress in 1834 and repeal of the constitution in 1835. However, given that representative governments had arguably not been fully consolidated in these countries, these power grabs were often seen as missteps along the path to fully implementing democracy, rather than coups.

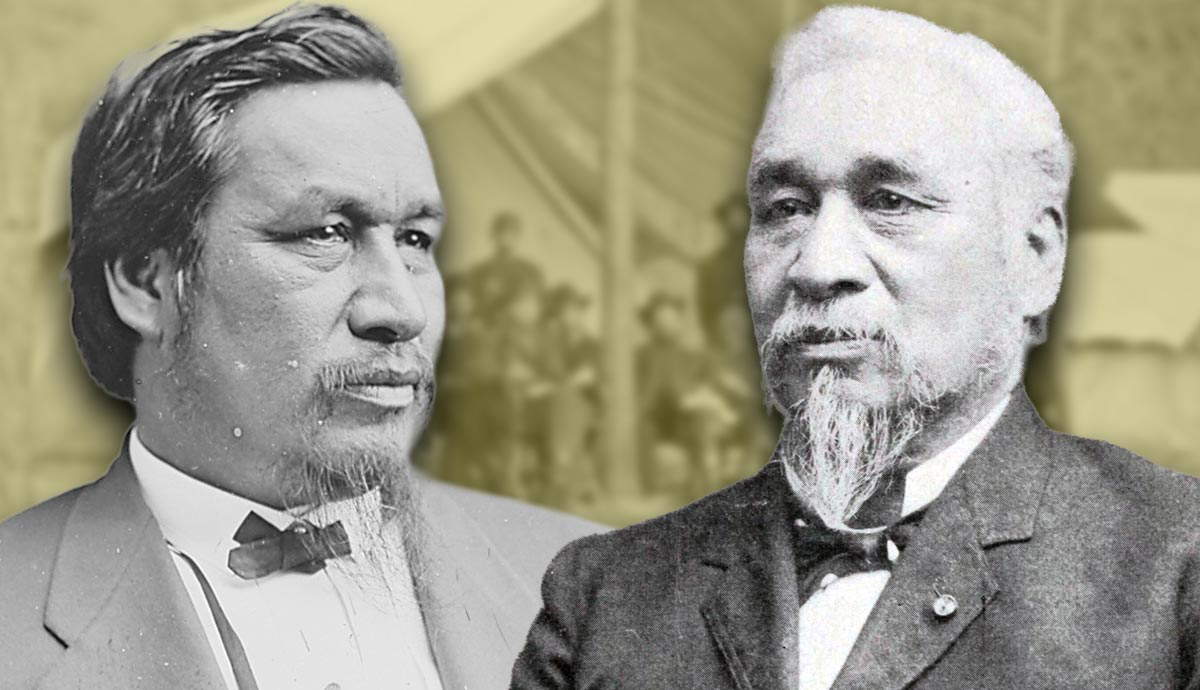

One successful autogolpe took place in Brazil in 1937, when the democratically elected Getúlio Vargas moved to install himself as a dictator. Though his rule, begun in 1930, had already been marked by authoritarian moves like suspending civil rights and declaring successive “states of emergency” that gave the government outsized policing powers, it finally came to a head when he “convinced” congress to sign a new constitution. With that done, the upcoming presidential elections were cancelled, opposition candidates arrested, political parties banned, and the media censored. For the next eight years, the country was largely ruled by decree until the military deposed Vargas in 1945.

Uruguay also faced not one but two events that could be termed self-coups, the first in 1933. Gabriel Terra had been elected in 1931 and faced a spiraling economic situation. He proposed reforming the constitution and dissolving the agency that set economic and social policies. Deciding that these reforms weren’t coming to fruition quickly enough, Terra dissolved the general assembly and began ruling by decree, censoring the press and silencing the opposition. Although a new constitution was ultimately adopted and a constituent assembly elected, Terra won an illegal second term and continued in power until 1938.

Again in 1973, the democratically elected candidate, Juan María Bordaberry, already employing a variety of authoritarian tactics, including the suspension of civil liberties and imprisonment of opposition candidates, moved to rule as a dictator. After just one year in office, Bordaberry dissolved congress and suspended the constitution. Awarding extraordinary powers to the country’s police and military, he ruled by decree, advised only by his security council, until he was forced to resign.

Despite these earlier examples, it was ultimately the dramatic government overthrow orchestrated by Peru’s president Alberto Fujimori in 1992 that brought widespread recognition to the term autogolpe.

Fujimorazo: The Quintessential Self-Coup

The quintessential self-coup, the one that cemented the word autogolpe in the lexicon of history, was Fujimori’s overthrow of his own legitimate government in Peru. Elected two years earlier in a country plagued by terrorist attacks from the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) guerrilla movement, Fujimori struggled to move his agenda through the country’s legislature, where his party was in the minority. In particular, opposition parties resisted the adoption of economic austerity measures being pushed by financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank.

On April 5, 1992, Fujimori suspended the country’s constitution, dissolved the legislature, dismissed senior judges, and placed prominent opposition officials under house arrest. Former president Alan Garcia barely escaped arrest and sought asylum in Colombia. Fujimori quickly adopted Decree Law 25418, giving himself all legislative powers and overriding the country’s constitution.

Often overlooked in recounting the autogolpe, the country’s military had, years earlier, drawn up plans for a “traditional” military coup, the so-called Plan Verde, which Fujimori adopted to launch his self-coup. It then comes as no surprise that all branches of the military promptly signed a communiqué supporting Fujimori’s new Government of Emergency and National Reconstruction—it was their own plan all along. The military took control of the nation’s media outlets and occupied government buildings, tear-gassing a group of politicians attempting to hold a session after Fujimori’s announcement disbanding the legislature.

International response to the self-coup was underwhelming. Although the general opinion was against Fujimori’s illegal moves, Peru was not suspended from the Organization of American States for violating the Inter-American Democratic Charter. Within two weeks, the US formally recognized Fujimori as Peru’s legitimate president. Domestically, Peru’s politicians and journalists rejected the autogolpe, but the Peruvian people, though perhaps limited in their understanding of events by media blackout, largely supported Fujimori. In fact, they would go on to re-elect him in 1995 in what were broadly considered free and fair elections. The Fujimorazo was a success.

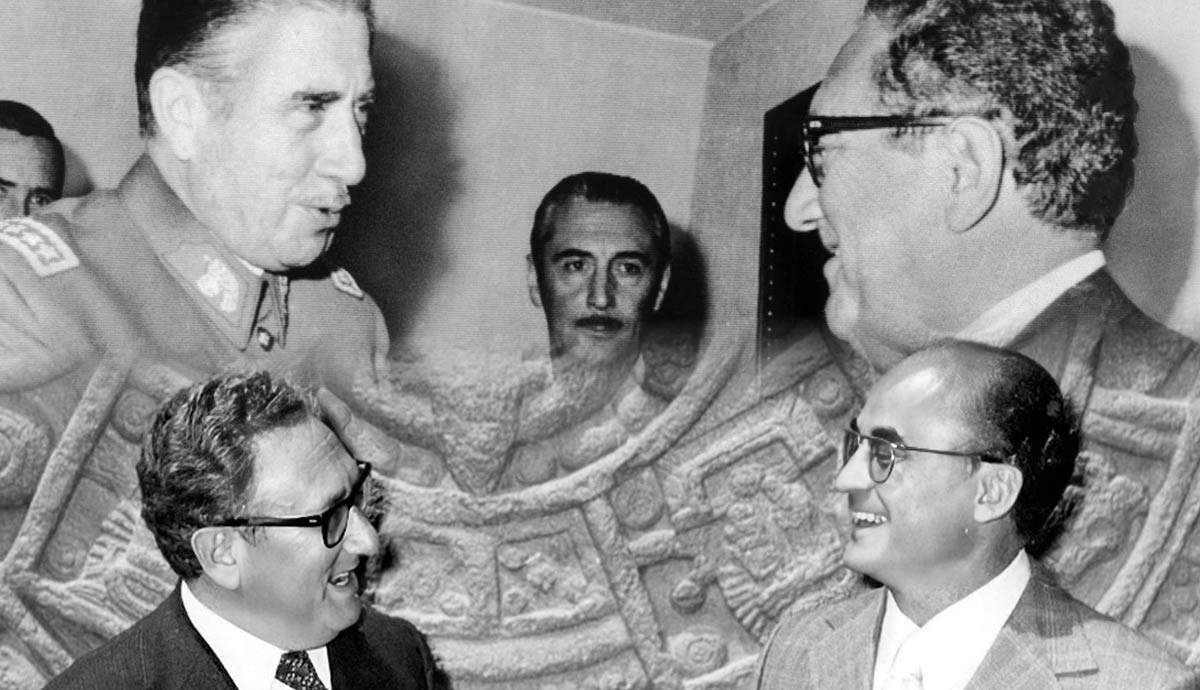

Guatemala 1993: The Failed Copycat Autogolpe

In 1993, the beleaguered president of Guatemala, Jorge Serrano Elías, who had apparently watched Fujimori’s autogolpe with great interest, attempted a similar power grab. Just two years earlier, Serrano’s accession to the presidency had marked the first peaceful and democratic transfer of power from an incumbent to the opposition in 40 years, a promising start. Yet, with the country amid a prolonged civil war and his party holding just 18 seats in the legislature, he was primed for a difficult term.

During his first two years, the country saw modest economic growth, and Serrano was able to reestablish civilian control over the military. Yet, he failed to sufficiently address the issue of human rights abuses by the military and right-wing paramilitaries and made little progress in securing peace with the leftist rebels, both key campaign promises.

Despite his party’s success in the 1993 mayoral elections, Serrano remained relatively weak politically, so his next step has long puzzled political scholars. On May 25, 1993, Serrano suspended the country’s constitution and closed congress, as well as the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court. Like Fujimori, Serrano proclaimed himself a champion of democracy, implementing these measures in order to root out the corruption in the very institutions of governance that were preventing democracy from thriving.

Unlike Fujimori, Serrano gravely overestimated his popularity and support, particularly with the military, which had been so key in Fujimori’s takeover. Widespread opposition to his maneuvers quickly coalesced among civil society, including key players like the press and the Catholic Church, international organizations condemned his takeover, and foreign governments imposed sanctions. By June 1, Serrano had resigned and fled the country. Democracy, though temporarily thrown into chaos, prevailed.

Autogolpes in the 21st Century

Despite the widespread consolidation of democracy throughout the Western Hemisphere, autogolpes have continued into the modern era, though they have evolved over time. Rather than outright disbanding the co-institutions of government, today’s self-coup often involves illegally co-opting the legislature and judiciary, undermining and ultimately rendering impotent the other branches of government, or simply ignoring them and daring anyone to stop them. There have been quite a number over the last two decades, including another attempted self-coup in Peru in 2022.

With Hugo Chavez’s death in 2013, Nicolas Maduro, then-vice president, took over Venezuela’s presidency. Venezuela was arguably already in dictatorship territory prior to Chavez’s passing, but the vestiges of democracy remained. Even those quickly fell apart. After the opposition won control of the National Assembly in 2015, Maduro quickly moved to fill the country’s Supreme Court with allies during “lame duck” assembly sessions and oversaw the removal of opposition candidates from the new legislature due to supposed electoral irregularities, ending the opposition’s supermajority.

The packed court, cancelling a recall referendum, awarded Maduro more and more authority, until he ultimately ordered it to take over the assembly’s legislative powers in 2017. After elections, widely regarded both at home and abroad as rigged, produced a Constituent Assembly favorable to Maduro, he declared the 2015 assembly dissolved. He remains in power today.

El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele has often referred to himself as the “world’s coolest dictator,” and the dictator part, at least, is not hyperbole. Elected in 2019, his party initially didn’t have enough legislative representation to push his agenda. His response, on one occasion, was to send soldiers into the legislative assembly to intimidate it into approving a loan request. After his party won the majority of seats in 2021, Bukele moved swiftly to ensure his ongoing authority. The five judges on the country’s Constitutional Court were removed, along with the attorney general, and new, Bukele-friendly judges took over. By 2022, Bukele had invoked the country’s infamous “state of exception,” suspending civil liberties like due process and jailing tens of thousands of “gang members” in order to bring order to a country plagued by violence. Despite a constitutional ban on consecutive terms, Bukele was inaugurated for a second time in 2024.

One unifying element of 21st-century autogolpes is that they are commonly referred to as “constitutional crises” until their success or failure is determined. These two examples of modern self-coups were without a doubt successes, but a number of constitutional crises elsewhere present additional threats to the supremacy of democracy over autocracy in the hemisphere.