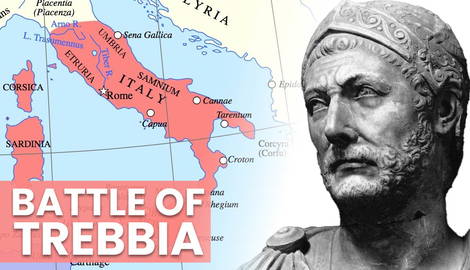

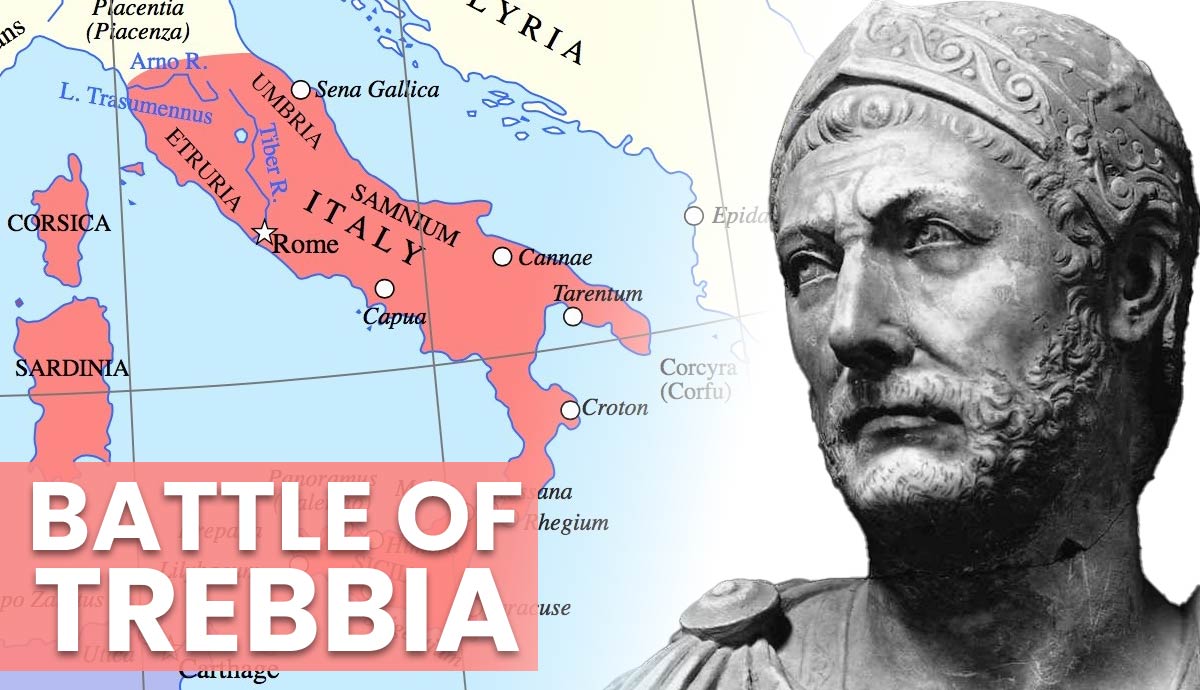

In 218 BCE, the Second Punic War erupted when Carthage captured the Spanish city of Saguntum, an ally of the Roman Republic. The war was one of the ancient world’s largest conflicts. It was fought across Spain, Italy, and Africa, eventually spilling over into Greece and Asia. During the early stages of the war, Rome suffered devastating losses at the hands of the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca. The Battle of Trebbia was the first of these terrible defeats, foreshadowing Hannibal’s military genius.

Before the Battle of Trebbia: The Impossible Route

Once the Roman Republic declared war on Carthage, they prepared their forces to invade Carthage’s territories in Iberia (modern-day Spain and Portugal) and North Africa. The Romans were, however, outmaneuvered by a stroke of genius, which many considered to be an act of madness at the time. Hannibal gathered his forces in Iberia, numbering 50,000 infantry, 9,000 cavalry, and 37 elephants. The Carthaginian general crossed the Pyrenees with his army and then ascended the impenetrable Alps in late autumn, crossing in two weeks. The entire journey was costly, and his army suffered terrible losses to ambushes from hostile tribes, and the harsh climate of the mountain passes. When Hannibal arrived on the other side of the Alps in Italy, he had a mere 20,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and only a small number of elephants left.

Nevertheless, Hannibal caught the Romans completely off-guard. Taking an army across the Alps was considered impossible. The Romans had planned to fight the war on enemy territory. Now, there was a hostile force right in their own backyard. While the Roman army heading to Iberia continued on its original mission, its main commander, the consul Publius Cornelius Scipio, returned in haste to take command of the Roman forces left in northern Italy.

Battle of Ticinus

Scipio gathered his army and set out to confront Hannibal. The two armies encamped close to one another on a plain on the right bank of the Ticinus River. The following day, both commanders set out with a strong reconnaissance force to inspect the enemy’s army. Hannibal’s forces consisted of Libyan and Iberian heavy cavalry and contingents of the elite Numidian light cavalry. Scipio, on the other hand, had a mixed force of Gallic and Roman cavalry supported by a force of javelin-armed velites, which were light infantry.

When the armies made contact, they drew up their battle lines. Hannibal placed his heavy cavalry in the center and his light Numidians on the wings. The Roman line had placed the Gallic horse and velites in the frontline with the Roman cavalry in the rear. As the velites advanced to discharge their javelin at the enemy, Hannibal’s heavy cavalry unexpectedly charged forward, driving the Roman light infantry back before they could cast their missiles. The Romans responded by charging the Carthaginian horse. A fierce hand-to-hand combat ensued, with many horsemen dismounting and continuing the battle on foot. The battle was won when Hannibal’s Numidians outflanked the Romans and charged their rear. According to the historian Polybius:

“Numidian horse, however, having outflanked the Romans, charged them on the rear: and so the sharp-shooters, who had fled from the cavalry charge at the beginning, were now trampled to death by the numbers and furious onslaught of the Numidians; while the front ranks originally engaged with the Carthaginians, after losing many of their men and inflicting a still greater loss on the enemy, finding themselves charged on the rear by the Numidians, broke into flight (3.65.10-11).”

Scipio barely survived, suffering a severe wound. He was saved only by the bravery of his 16-year-old son, also named Publius Cornelius Scipio. The younger Scipio would be awarded the agnomen Africanus for his later victories in North Africa. The surviving Romans withdrew to their camp, and the army retreated under the cover of darkness.

While Ticinus was only a minor engagement, it shocked both the senate and the army under the consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus, who was heading for Africa. He was recalled to defend Italy. Hannibal’s army was reinforced with a great number of Gallic and Ligurian warriors who flocked to his side to join his cause.

Preparations For Battle

Sempronius’ army joined up with Scipio’s in December 218 BCE. The two armies were encamped a few kilometers apart on either side of the Trebbia River. In Sempronius, Hannibal faced an ambitious general who was glory-hungry and eager for a pitched battle against the Carthaginians before his term as consul was over. Scipio, however, having seen what Hannibal was capable of, was against open engagement.

The Romans won a small skirmish against one of Hannibal’s raiding parties, which only served to embolden Sempronius. Hannibal himself was also eager to engage the enemy in pitched battle. He wanted to prove to his new Gallic allies that they had backed the right horse and to boost the morale of his own men with a decisive victory. Having carefully chosen an open plain beside an overgrown, dry watercourse, the ideal terrain for maximizing his cavalry superiority, Hannibal provoked the rash and impetuous Sempronius into battle.

The Battle of Trebbia

On a cold, snow-covered December morning, just as dawn was breaking, the Romans were awakened by the war cries of howling Numidian riders attacking their camp. Sempronius immediately ordered his cavalry, supported by 6,000 elites, to engage the brazen Numidians, who retreated to their camp. He then assembled his entire army and marched them out to meet the Carthaginian host.

The Roman army, which marched out without breakfast, made the difficult crossing over the freezing Trebbia River that came up to the infantry’s chests. By the time the army formed on the other side, the soldiers were visibly shaking and fatigued. According to Livy:

“But when they entered the water which had been swollen by the night’s rain and was then breast high, their limbs became stiff with cold, and when they emerged on the other side they had hardly strength to hold their weapons; they began to grow faint from fatigue and as the day wore on, from hunger (21.54.9).”

In contrast, the Carthaginian army they faced was well-fed, well-rested, and kept warm by their fires. Furthermore, the night before, Hannibal had selected 2,000 of his best infantry and cavalry to set an ambush for the Romans. The 2,000 soldiers were concealed in the old, overgrown watercourse, waiting for the right moment to spring their trap.

The Romans numbered 36,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry. Hannibal had 8,000 light infantry, 20,000 heavy infantry, and 10,000 cavalry. The armies were thus similar in size, but the Carthaginians had the superior cavalry arm. Both armies placed their heavy infantry in the center with their cavalry on the wings. The Carthaginian heavy infantry, being inferior in number to the Romans, had their flanks protected by the few remaining elephants that survived the crossing of the Alps. Both armies had their main force screened by light infantry.

The battle commenced with the light infantry engagement. Here, the Carthaginian slingers and javelin men got the better of the Romans due to the velites having spent most of their javelins in the engagement with the Numidians. Sempronius thus ordered his heavy infantry to engage. The light troops on both sides retreated through the ranks of the heavy infantry. The Romans charged the Carthaginian lines, and a brutal melee engagement ensued. On the wings, the Carthaginian cavalry, being well rested and outnumbering the Romans, were quick to drive off the Roman horse on either flank of their infantry. With the Roman flanks exposed, the Carthaginian light troops outflanked the Roman infantry and attacked them in the flanks. The Roman infantry were now facing enemies to their front and on both flanks.

Suddenly, the Romans heard the terrible sound of war cries from their rear as 2,000 horsemen and infantry charged down upon them, causing great chaos and distress. Hannibal had sprung his ambush. The Romans were now surrounded, fighting on all fronts and taking heavy casualties. A contingent of Romans in the van, numbering 10,000, managed to cut their way through the Carthaginian line and retreated to the safety of the city of Placentia. According to Polybius, “of the remainder, the greater part were killed near the river by the elephants and cavalry.” Those who survived were saved only by an intense storm that stopped the Carthaginians from pursuing their defeated foes any further.

Hannibal had won a great victory over the Romans. He had now beaten two Roman consuls in the space of a few weeks. Unfortunately, the sources do not specify the number of casualties on either side, but Hannibal’s army was mostly intact, having lost very few of his African and Iberian veterans. His heaviest casualties were suffered by his newly gained Gallic allies. What elephants he had left after his crossing of the Alps, however, succumbed to the cold and wounds. Only one of the beasts remained. The Romans suffered far greater losses and were severely beaten on home soil.

Battle of Trebbia: Aftermath

Hannibal had shown his military genius by using a variety of superb military tactics at the Battle of Trebbia. Not only did he use the natural elements and the terrain to great effect, but he also used the rash character of the Roman general against his enemy. This was, however, only the beginning. Hannibal would continue to win a series of brilliant victories over the Romans that would cement his legacy as one of history’s greatest military minds.