Christmas poems can be traced back hundreds of years, with verses acknowledging the birth of the Christ Child evolving over decades into modern odes to Christmas trees, holiday shopping, and even Christmas dinner.

Read on below to discover eight classic Christmas poems, spanning 300 years of literature.

1. Christmas (1954) by John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman was a celebrated English poet, writer, and broadcaster who served as Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death in 1984. His poetry is synonymous with clarity, a yearning for a bygone England, and a focus on the architecture and class structure of English society. Betjeman wrote regularly on suburban life, the middle class, and a waning national faith. His poetry often blended satire with spirituality, resulting in a stark, profound effect. Much of his work is melancholic; a sentiment that translates to the festive season seamlessly.

Christmas opens with a review of the commercialized excesses that dominated the holiday season in Britain in the mid-20th century. The “tinsel and the bells and the beer” are presented as distracting indulgences that lie in stark comparison to a simple, timeless Christmas that honors Christianity at its center. He juxtaposes the frivolity of consumerism with the enduring solemnity of the Nativity:

“And is it true? And is it true, This most tremendous tale of all,

Seen in a stained-glass window’s hue, A Baby in an ox’s stall?”

Betjeman leaves the reader to meditate on the tipping scales of Christmas meaning. How do we acknowledge reverence and religion in an increasingly commercialized arena?

2. Christmas Trees (1916) by Robert Frost

Robert Frost was, and remains, one of the most prominent names in American poetry. Famed for his careful descriptions of rural New England life and his cerebral meditations on autonomy and chance:

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both.”

Frost’s use of accessible language to explore philosophical multitudes cemented his voice as a public favorite. Born in San Francisco in 1874, Frost moved to Massachusetts with his mother and sister after the death of their father from tuberculosis when Frost was eleven years old. His time in Massachusetts was one of literary discovery. After high school, he attended Dartmouth and Harvard. In 1912, Frost and his wife Elinor Miriam White (with whom he shared valedictorian honors in high school) moved to England. Here, Frost’s literary career took off, and he published his first two full-length poetry collections.

By the time he returned to the States in 1915, he was one of the most celebrated poets in America, and with each new book, his honors only increased. His career was full of glittering highlights; he became the only poet to win four Pulitzer Prizes. He recited The Gift Outright at John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inauguration, received the Congressional Gold Medal, and received over 40 honorary degrees.

In his 1916 poem, Christmas Trees, Frost’s thoughtful verse describes a man from the city visiting the narrator’s farm. The city man wants to purchase the narrator’s entire stock of fir trees for profit. The poem unfolds conversationally from here, with the speaker contemplating such an unexpected interest in his ordinary evergreens. But to cut down so many trees would surely be a mistake? Frost contrasts the inherent natural value of the country with the mercenary manufacturing of the city:

“A thousand Christmas trees!—Come, I was wrong.

Come, I consider: What is one man’s want?”

With this, Frost asks whether beauty can be bought. And if so, is it worth the cost?

3. A Christmas Childhood (1943) by Patrick Kavanagh

Iconic poems such as The Great Hunger and On Raglan Road established Patrick Kavanagh as a vital Irish voice in the post-Yeats era. Born in County Monaghan, Kavanagh was self-educated, having left school at the age of 12 to work on his family’s small farm. Thereafter, Kavanagh taught himself about words, literature, and poetry. When he moved to Dublin in 1939, after a brief stint in London, he settled in the city for the rest of his life.

Kavanagh began his career amid the final years of a cultural movement known as the Irish Literary Renaissance, characterized by rising nationalism, which would eventually lead to Ireland’s independence from Great Britain after World War I. Freed from the shackles of traditional English literature, Kavanagh concentrated on Irish subjects that felt familiar, yet undiscovered. Cultural independence was the goal.

Made richer by this context, A Christmas Childhood is a poignant, nostalgic piece that recalls the awe and simplicity of Kavanagh’s earliest rural Irish Christmases. With child-like sincerity, he recalls tangible, sensory details such as the smells of burning peat and the sounds of harsh winter winds. He anchors the detail in earthiness, avoiding shallow waters:

“I can remember the fierce energy of the stars

That fell with the turf-sods on the fire,

The parsimonious glitter of glow-worms.”

Kavanagh notes that the spiritual truth of Christmas does not necessarily lie in strict religious doctrine, but rather in the innocent imagination of a child experiencing the world. Perhaps, he suggests, the most lasting form of magic can be found in the melancholic recollection of a simple, happy past.

4. On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity (1645) by John Milton

John Milton was born in 1608 in London to a prosperous and educated family. Most famously known for his epic Paradise Lost, Milton produced copious publications throughout the 1600s, all while slowly losing his eyesight. He worked as a poet, political writer, government official, and university professor. His writing reshaped the possibilities of the English language and was grounded in his lifelong belief that words could carry moral weight and political potency.

During the English Civil War, Milton wrote reams of paper defending freedom of speech, religious tolerance, and the civil right to challenge authority. When Oliver Cromwell took power in England, Milton joined the new government as a civil servant specializing in foreign languages, translations, and the drafting of new state papers.

Though it was published much later in 1645, Milton wrote On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity in 1629, while still a student at Christ’s College, Cambridge, utilizing his deep grasp of both classical texts and Christianity. The lengthy ode reflects on the impact of Christ’s birth on the spiritual world, and envisions a sublime peace falling over the world, quietening the false pagan deities faced by divine light. He comments on the immense, universal scope of the event:

“But peaceful was the night

Wherein the Prince of Light

His reign of peace upon the earth began:”

The poem reaches further than recounting the Biblical story, but rather, it posits a major theological statement. Did the Nativity mark a point in cosmic time where harmony briefly overpowered the darkness inherent in the subsequent human world?

5. [little tree] (1920) by E. E. Cummings

Edward Estlin Cummings was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1894. He grew up in a household that encouraged creativity and saw him study at Harvard. During World War I, Cummings served in an ambulance unit; an experience which cemented his belief in individuality, an idea which would run through almost everything he wrote in the postwar period.

Cummings bent the rules of grammar, punctuation, and structure. His experiments were ground-breaking and exhaustive. By the time of his death in 1962, Cummings had become one of the most recognizable voices in modern American poetry.

He gave his 1920 Christmas poem a stylized title with an unconventional use of lower-case letters, which was by now typical of Cummings:

[little tree]

In the poem, the speaker addresses a Christmas tree directly. The tree is delicate, fragile, and requires tenderness. The little action revolves around the act of bringing the tree inside the house and decorating it. The innocent speaker feels protective of the little tree:

“little tree

little silent Christmas tree

you are so little

you are more like a flower

who found you in the green forest

and were you very sorry to come away?”

In personifying the tree, it takes on a human quality and encourages the audience to acknowledge the connection between the natural world and the human one, particularly during the holiday season.

6. The Twelve Days of Christmas (1780) by Unknown

For such a well-known poem, The Twelve Days of Christmas has a bizarrely obscure history. The earliest documented version appeared in a 1870 children’s book called Mirth Without Mischief. It makes sense that the poem was designed for children, as it operates as a cumulative verse, easily memorized and recited. The original author remains unidentified.

The catalog of gifts received from the speaker’s “true love” allows for a window into the domestic and upper-class life of the period, with gifts encompassing everything from quite ordinary poultry to high-value jewelry.

The poem consists of an expanding concertina of extravagant presents given each day over the twelve days of Christmas—namely, between Christmas Day and Twelfth Night (January 5). Traditionally, this marked the journey of the Magi to Bethlehem to see the Christ Child.

The famous stanzas are simply repetitions, with each verse introducing a new gift while reiterating the previous ones. It has been suggested that the poem might have first been intended as a parlor game, or a memory game of sorts. The idea is that each player remembers as many items as possible or pays a penalty.

The ever-growing bounty of generosity begins with:

“On the first day of Christmas, my true love sent to me: A partridge in a pear tree.

On the second day of Christmas, my true love sent to me: Two calling birds and a partridge in a pear tree.”

The joyful, playful rhythm is a natural fit to music, but it was not given such a score for another 100 years. In 1909, English composer Frederic Austin set the words to melody, including a drawn-out and climactic “five gold rings.”

Still sung every December, The Twelve Days of Christmas is a guiltless celebration of lavish romantic pursuit and festive abundance.

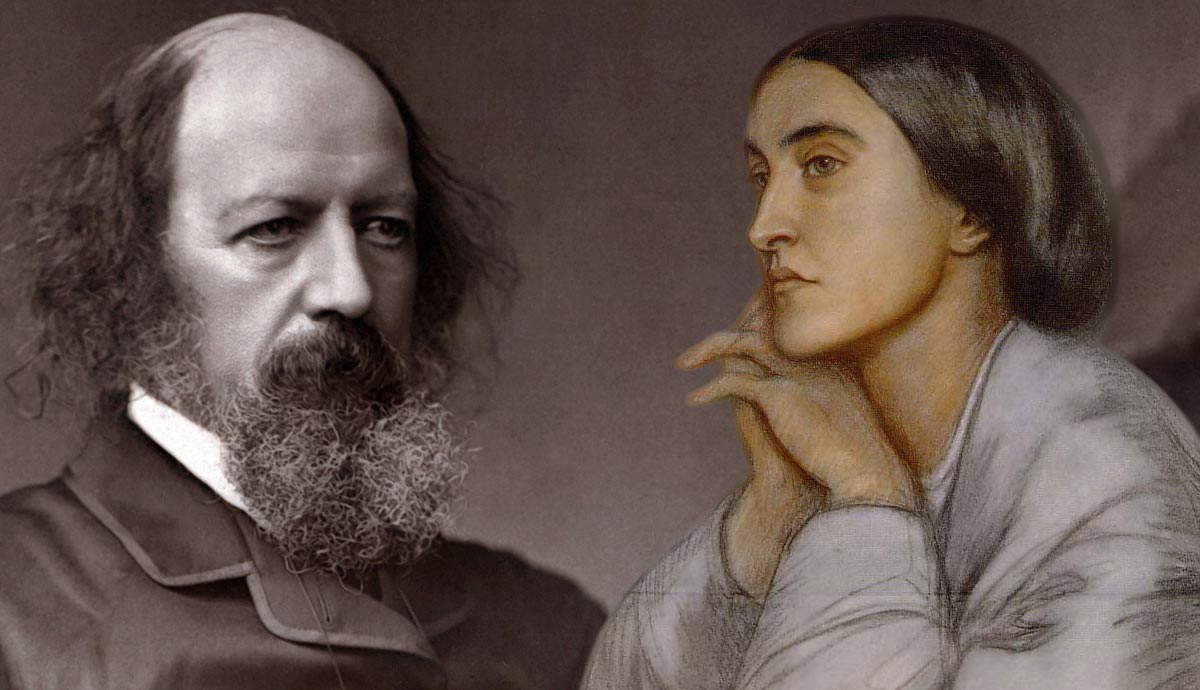

7. Christmas Carol (1911) by Sara Teasdale

Sara Teasdale, born in 1884 in St. Louis, Missouri, was an American lyricist celebrated for her deeply personal poetry on the inner life, nature, and love. Her language was simple and highly musical, and frequently explored themes of love, beauty, solitude, and mortality.

She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1918 for her collection Love Songs, and her presence in the 20th-century poetry scene was prominent. Teasdale battled depression throughout her life and would articulate this struggle in her poetry.

Her 1911 Christmas poem, Christmas Carol, deliberately moves away from traditional tellings of the Christmas story and instead concentrates on the serene minutiae of the comings and goings within the Nativity:

“The shepherds came from out of the north,

Their coats were brown and old;

They brought Him little new-born lambs—

They had not any gold.”

The comings and goings are described as though a stream of visitors is entering and exiting gently through a maternity ward to see a new mother and her newborn baby:

“The kings they knocked upon the door,

The wise men entered in,

The shepherds followed after them

To hear the song begin.”

In so doing, Teasdale reduces the Christmas story to the confines of the stable, in which well-meaning visitors come to give their love, and, though the world outside awaits, those in the stable are safe, at least for now, from its inevitable interference.

8. Talkin’ Turkeys (1994) by Benjamin Zephaniah

Talkin’ Turkeys was written in defense of the Christmas bird eaten in millions of homes on Christmas Day. Benjamin Zephanah was a writer, dub poet, and musician born in Birmingham, UK. His poetry tackled the everyday lives of Britons and was heavily influenced by Jamaican music, poetry, and culture. Zephaniah pioneered performance poetry and, as well as an accomplished actor, he became one of Britain’s top poets. All this despite having left full-time education at the age of 13. Famously, Zephaniah turned down an OBE in 2003, saying, “I get angry when I hear the word “empire”; it reminds me of slavery, it reminds me of thousands of years of brutality.”

Talkin’ Turkeys includes a confrontation with a personified turkey, who asks Zephaniah, “Who put de turkey in christmas? Zephaniah replies:

“I am not too sure turkey

But it’s nothing to do wid Christ Mass

Humans get greedy an waste more dan need be

An business men mek loadsa cash”.

A life-long Rastafarian and a vegan, Zephaniah invites us to consider traditions through a new lens. By anthropomorphising the turkey and presenting the birds as sentient beings with mothers and families, we are encouraged to empathize with them and their animal kingdom. The turkeys ask whether, just this year, we might try something new…