Recognized as ‘alaxulux’en in the Chumash language, the Chumash Painted Cave once operated as a ceremonial site. Due to colonization and the establishment of Spanish missions in Chumash territory, traditional use of the cave ceased over 300 years ago. Vibrant hues of red, white, and black adorn the cave walls, depicting figures, animals, and shapes believed to have been painted by shamans. Today, members of the Chumash community are working to revitalize their languages and traditions, with the cave remaining an important heritage landmark that connects them to their ancestors.

Discovering the History of the Chumash Painted Cave

The Chumash Painted Cave, part of the Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park, is known to the Chumash as ‘alaxulux’en. Located at the edge of the traditional Barbareño Chumash territory, or present-day Santa Barbara, California, the small cave can be viewed by visitors from a distance. Once serving as a ceremonial site, ‘alaxulux’en represents some of the last preserved wall art of the Chumash people, offering modern descendants a connection to their ancestors.

The Chumash have lived in central and southern coastal regions of California for over 10,000 years. Before European contact, the Chumash lived in a network of up to 100 villages encompassing modern-day Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, San Luis Obispo Counties, and nearby islands, with a population of over 15,000. Spanish missions were established in Chumash territory in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, leading to the forced conversion of many Chumash people to Catholicism. This period resulted in significant changes for the Chumash community, including the loss of land, the erasure of languages and cultural practices, and a devastating decline in population due to introduced diseases and violence.

As the Chumash Painted Cave has been subject to harm from graffiti and flash photography, CyArk collaborated with California State Parks and Barbareño Chumash Elder Ernestine Ygnacio-De Soto to virtually preserve ‘alaxulux’en using 3D documentation. Ygnacio-De Soto is the great-great-granddaughter of Maria Ygnacia, the daughter of the last wot, or chief, of Syuxtun, a large Chumash settlement. Her mother, Mary Yee, was the last surviving first-language speaker of Barbareño, one of the Chumash languages once widely spoken in the region, which Ygnacio-De Soto is active in documenting.

Life Between the Mountains and the Sea

The rich culture of the Chumash tribe has strong ties to the land and sea, with their ancestors having resided between the Santa Ynez Mountains and the Pacific Ocean. Coastal towns thrived from the abundance of resources. As a maritime culture, the Chumash had extensive trade partners, with trade facilitated by shell bead money and trail systems. Skilled craftsmen constructed planked oceangoing canoes, called tomols, for fishing and trading, as well as delicate beadwork, bows, bowls, and baskets.

Hunting, gathering, and fishing were fundamental to the Chumash of the mainland coast, using extensive knowledge of various plants and animals. Their spiritual belief system is central to their everyday life and is deeply intertwined with nature, with the belief that the Sun and Earth are in balance. Oral storytelling, an elaborate tradition of the Chumash people, is central to cultural transmission, allowing future generations to retain cultural knowledge.

Members of the ‘antap society, who held high-ranking status in a tribe, directed the spiritual life of a group. Shamans within the ‘antap were responsible for ceremonies, including solstice observances and cave paintings. The ‘alchuklash, astronomers and priests of the ‘antap, possessed knowledge of the celestial cycles and calendars. In particular, the summer and winter solstices held significance, with accounts of rituals, leaving behind rock art with symbolic remnants of ceremonies.

The Vibrant Pictographs of the Chumash Painted Cave

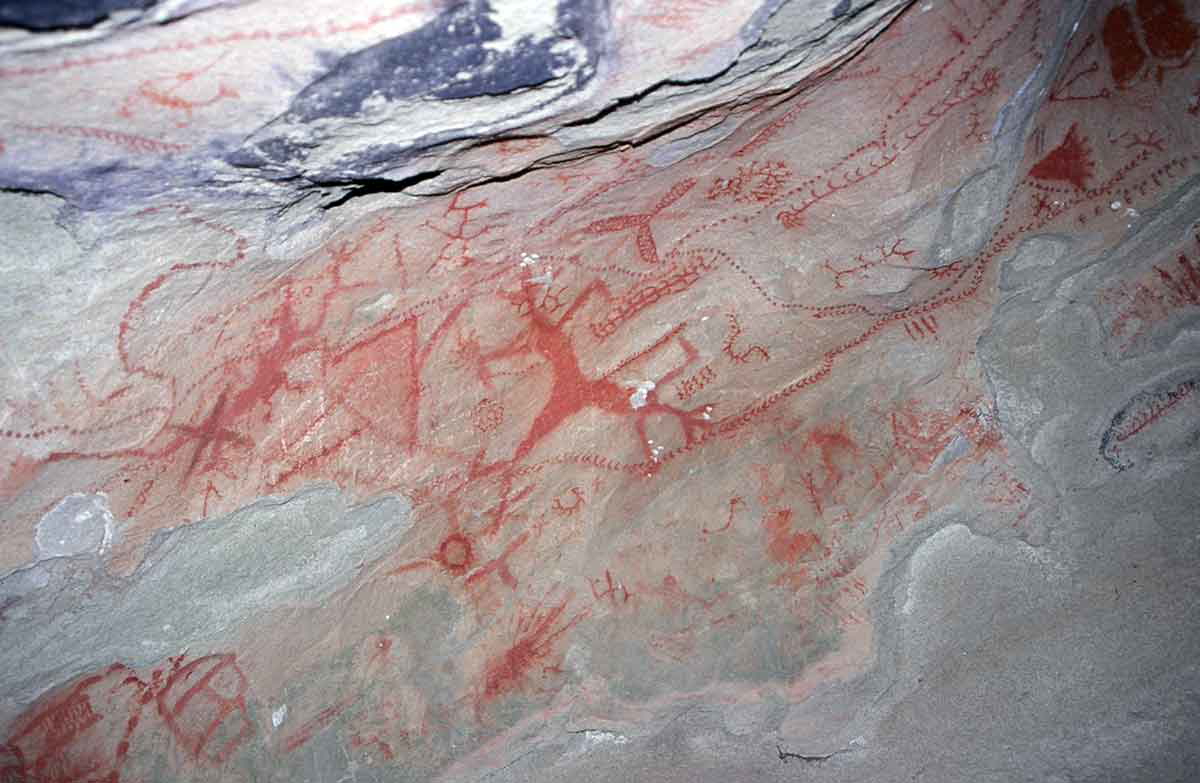

The paintings, tracing the contours of the sandstone walls, remain vivid in bold hues of red, black, and white. Archaeologists have determined that the artists concocted the pigments used to paint the cave with a variety of minerals. They mixed the bold red pigments using red ochre, or hematite, while the white used either gypsum or diatomaceous earth. To produce the bold black pigment, the artists would have used charcoal or manganese oxide. After grinding the pigments, the Chumash painter would mix them with a binder containing animal fat, sap, water, blood, or saliva, then use their fingers or a brush made from an animal tail to stain the cave walls.

On the walls are pictographs—illustrations made on rock—that depict human-like figures, animals, and abstract geometric shapes. Despite their age, the circles, spirals, figures, and celestial symbols remain vibrant in color. Anthropologists estimate the rock art to date back to the 1600s at the latest, with layers of the painting dating earlier than others.

The Distinct Styles of ‘Alaxulux’en

Researchers studied pigments from the paintings to identify four distinct styles in the cave. The first and oldest layer was painted using only charcoal, consisting of narrow lines and cross-hatching. These lines are faint, particularly due to the overlapping red lines of the second identified style, which were created with ground ochre.

The most complex and widespread of the four, style three represents anthropomorphic figures, animals, and geometric shapes. The third layer of the rock art consists of black and white centipede-like striped shapes and red figures with arms extending outwards. Rather than standing alone, the last style appears to add to the previous styles, supporting that people sought to maintain and improve upon the earlier rock art.

The Ceremonial Art of Shamans

As a result of the effects of colonization, the Chumash tradition of storytelling has been largely erased, including passing down the meanings behind pictographs. While many attempts have been made to interpret cave paintings, it is important to note that our modern interpretations are largely biased, and we should approach such artwork with the understanding that we will never fully perceive the intended meaning.

An earlier, now outdated theory from the late 1800s saw the circular designs of Chumash rock art as bundles of tied blanket bundles. During the same period, elder Ernestine’s great uncle Pedro Ygnacio described what he had learned from his elders. Pedro saw the paintings as representations of tomols that took the souls of the dead to the afterworld shimilaqsha and the centipede-like figures as illustrations of the cause of death.

Another belief is that the rock art was often created in response to crises, painted by shamans to appease the universe during difficult or unexplainable events. This approach is supported by the apparent increase in ceremonies in the inland following the arrival of the Spanish. Further ethnographic evidence suggests that the images were created as part of rituals to request fruitful harvests, rainfall, and fertility, as well as to ward away storms.

Many interpretations, reflecting on Chumash culture and traditional practices, indicate that members of the ‘antap society were the creators of the paintings. Taught by her grandparents, Chumash healer Cecilia Garcia expressed that the pictographs were primarily used as healing images. Patients would travel to caves close to streams, where the ‘antap painted pictographs to relax patients as part of the healing process or to show patients parts of the human body.

Mind-Altering Properties of the Datura Plant and the Red Harvester Ant

Momoy, a hallucinogenic plant called datura, was named after an older woman who personifies the plant in the Chumash culture. The ‘antap prepared momoy for ceremonial and medicinal purposes, including the initiation of young boys into adulthood. Chumash shamans took momoy to create a state of altered consciousness, leading the user to see the present or future more clearly through vision quests.

Red harvester ants, used by many indigenous groups in southern and south-central California for their hallucinogenic properties, were similarly ingested in the Chumash culture. Considered safer than momoy, the ants, known as shutulhul, were administered to induce sacred dreams or hallucinations for initiation ceremonies and traditional remedies.

While many have advocated for the theory linking the influence of hallucinogens like datura to the creation of rock art, there has been a lack of concrete evidence to support this. That was until archaeologists discovered wads of chewed datura in the ceiling crevices of a rock site called Pinwheel Cave in the Chumash borderlands of interior south-central California. Researchers believe the pinwheel-shaped painting represents a datura flower and suggest that an insect-like figure nearby could be a hawk moth, known to pollinate datura plants. Rather than a singular shaman, researchers theorized that the cave was used communally, as evidenced by the tools and artifacts discovered below the painting.

The Solar Eclipse of the Chumash Painted Cave

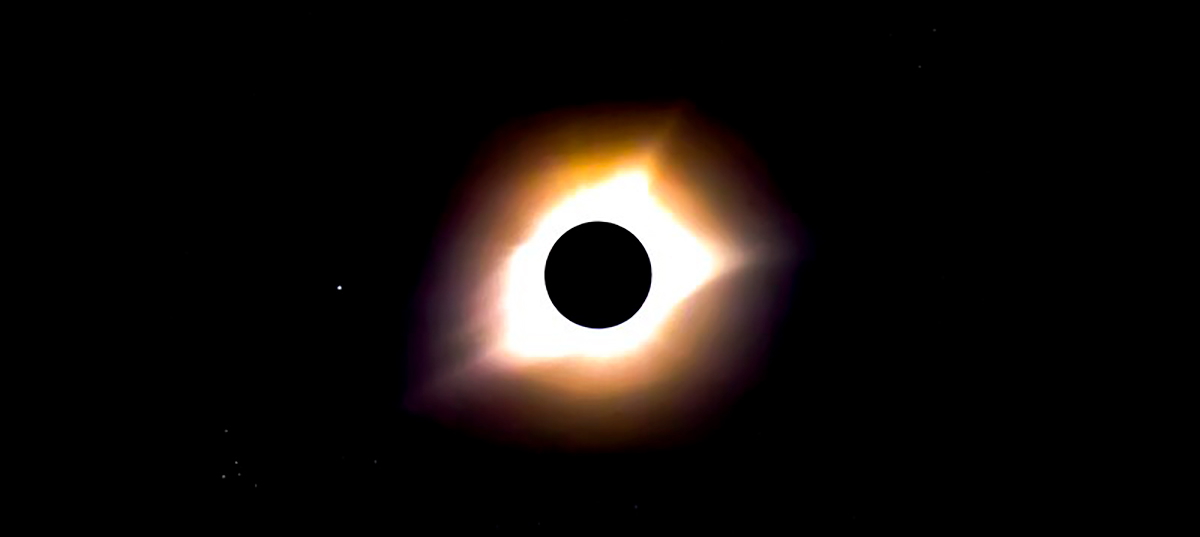

The Chumash identified many of the constellations in the night sky, using their knowledge of astronomy to track both time and seasons. Oral traditions and myths frequently featured celestial bodies, such as the legend of the Milky Way, Alchupo’osh, which saw the galaxy as a pathway to the afterworld. It is thought that the paintings in Chumash Painted Cave may have represented celestial beings, including the Sun, Moon, and Stars. Members of the ‘antap society would have painted such beings to maintain balance in the supernatural forces.

Using Oppolzer’s Canon of Eclipses, astronomer Katherine Bracher determined that a total eclipse would have occurred at the site on November 24th of 1677. Bracher identified a particular scene in the cave, featuring a black circular shape, as representing the solar eclipse. Below the black disk are two red circles, believed to symbolize Mars and the star Antares, which would have formed a visible triangular grouping with the eclipsed Sun. Black pigment carefully scraped from the disk was dated to the time of the eclipse, supporting the theory.

Preserving a Cultural and Historical Landmark

In 1908, officials constructed a protective iron gate to protect the priceless artwork from external threats. Beside the iron gate, the sandstone exhibits hundreds of dates and names thoughtlessly carved by visitors. A similar story can be told for the interior, as the cave walls exhibit acts of vandalism from as early as the missionization period. At present, the painted cave is threatened by wind erosion, steadily causing the ceiling to collapse. A gap within the paintings can be observed upon entering the cave site, which, in time, will expand.

In reference to the efforts made to revitalize many of the traditions and languages that were impacted by past travesties, elder Ernestine Ygnacio-De Soto described the Chumash culture as “sleeping,” rather than being lost. Today, ‘alaxulux’en remains a site of cultural and historical significance, inspiring the protection of the site for future generations. The paintings are deeply respected and symbolize the journey in which the Chumash have come, representing the resilience of a culture that has survived centuries of turmoil.