In 79 CE, the disastrous eruption of Mount Vesuvius destroyed the prosperous cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum near Naples. A densely populated city was buried under ash, lava, and stone, but its life was not over. Groups of survivors went on to rebuild their lives in other places, and Pompeii itself gained a surprising new status. Read on to learn more about Pompeii’s life after death and the survivors’ stories.

Pompeii Days Before the Catastrophe

Today, the remnants of Pompeii are one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world, continuously visited by millions of tourists. In its death, it became much more famous than it was in life. However, in its prime days, Pompeii was a prospering and rather large city that was home to around 30,000 citizens. Located next to the Bay of Naples, it provided opportunities for sea travel and trade, as well as agricultural production. It was the cultural center of the region with well-developed infrastructure that included public baths, fast food places, theaters, and other entertainment. Herculaneum was a smaller town of no lesser importance, used as a trading post. The contemporaries praised the beauty of the place, often specifically mentioning the perfectly symmetrical peak of Mount Vesuvius that loomed on the horizon.

The Eruption

The Pompeii locals knew about Vesuvius’s disastrous potential. Texts written by local naturalists observed volcanic activity and frequent eruptions—although not as catastrophic as the most famous one. Local religious cults included frequent sacrifices to the god Neptune, responsible for earthquakes and eruptions, and deities in the form of snakes, possibly capable of negotiating with the angry earth.

On August 24, 79 CE, Vesuvius exploded, turning the sky black with ash and pebbles. Huge fragments of stone blocked the seashore, which was the only hope for evacuation for many. Later, archaeologists found the remains of 300 people who waited for boats to come to their rescue. Contrary to popular belief, the eruption did not happen instantly. It lasted over eighteen hours and gave some of the locals time to escape. Others, in shock and panic, were not as lucky, caught mid-flight by the layers of volcanic material. So far, no more than 2,000 bodies have been excavated on both sites. This gave archaeologists a clue that the majority of citizens could have survived the disaster.

Survivor’s Records

Archaeologists and historians insist that the general idea that at least some part of the Pompeii population managed to escape was never disputed, yet it was barely studied. Most professionals working on the site noticed the absence of carriages and horses’ remains in stables, indicating that many people at least tried to escape the city. Still, for centuries, the focus of research was put on the immediate victims of the disaster, buried under the ash.

The most famous account of the Pompeii tragedy survivor refers to the ancient historian Pliny the Younger. He described his experience in two remarkably preserved letters written 25 years after the tragedy. He described the eruption in such great detail that present-day volcanologists were able to reconstruct the entire chain of events. He also described the death of his uncle, philosopher Pliny the Elder. Although he was in relative safety, he decided to travel to Herculaneum to study the volcano and to save some of his friends there, ultimately suffocating in toxic volcanic fumes.

Only recently, Miami University professor Dr. Steven L. Tuck conducted years-long research tracing the fates of Pompeii’s survivors and their attempts at rebuilding their community. Tuck gathered a list of names specific to the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum and traced the mentions of them in the nearby Roman towns and settlements. Moreover, he looked for infrastructural facilities that could indicate a large influx of refugees, such as emergency housing.

Over eight years of research, Tuck tracked down 200 migrants from Pompeii in 12 Roman cities. Most of them chose to remain within their native area, settling in cities unaffected by the eruption. One of the families researched was the Caltilius, who settled in Ostia, a well-developed port city near Rome. They found a temple to an Egyptian god they worshiped and joined families with another clan of survivors through marriage.

Some merchant families successfully revived their businesses in new locations, but many were not as lucky. The already poor families became even poorer outside of their native area and tried to hold on to each other, adopting orphaned children of other survivors and sharing resources. Some refugees occasionally returned to Pompeii and Herculaneum to look for their lost belongings, possibly facing groups of vandals and marauders ravaging the area.

Pompeii After the Tragedy

Unlike many other ancient cities rediscovered over the centuries, Pompeii and Herculaneum were never truly lost. Vague records of the lost cities could be found in old written sources. The name of the city was preserved on maps in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period. Still, major excavations of the sites were launched in the 18th century, when workers accidentally discovered the remains of Herculaneum while constructing a summer residence for the King of Naples. Stunned by the quality and the scale of their discovery, the King soon arranged further excavations. Art found in Pompeii villas revolutionized European understanding of antiquity, filling the blanks in their understanding of the progression of painting, sculpture, and architectural styles.

In the 17th to 19th centuries, Italy was similarly popular among tourists as it is today, yet with several important distinctions. The tourists were mostly wealthy young men from all over Europe who traveled to Italy for the so-called Grand Tour. This trip was supposed to finish their classical education based on Antique and Antiquity-inspired understanding of sciences, philosophy, and art. Pompeii was an important part of the journey, granting them the ability to see the everyday reality of Romans. Among these privileged tourists were famous artists who later documented their experiences.

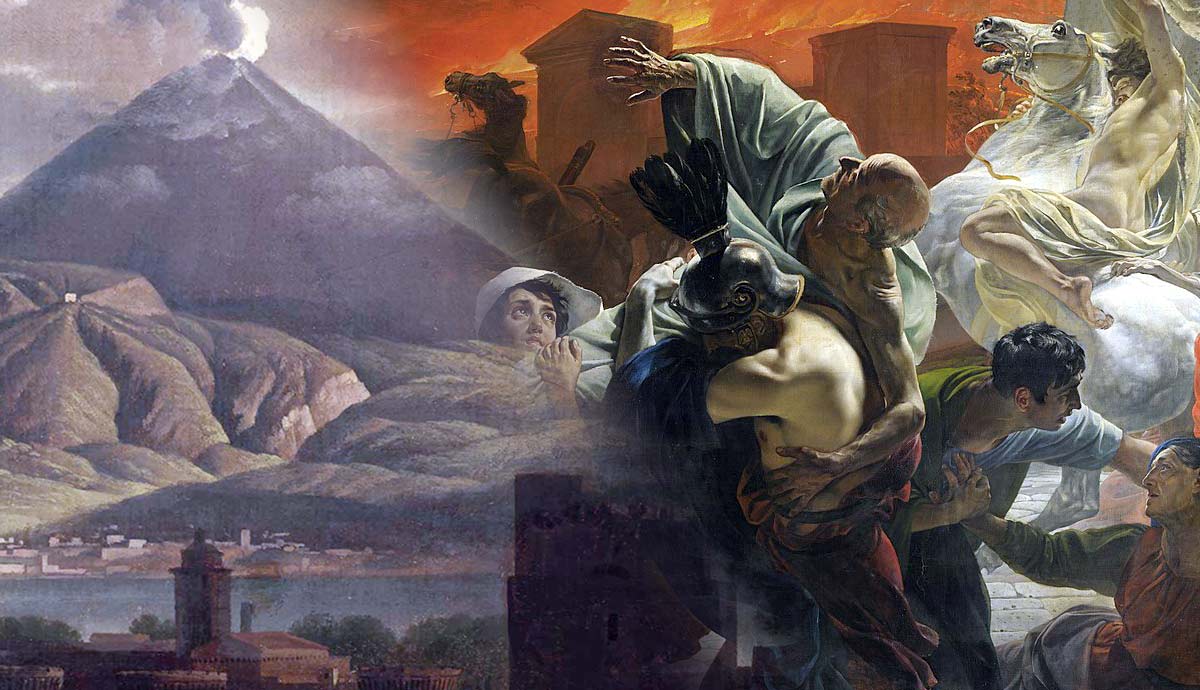

Russian artist of French origin Karl Bryullov was among those artists who went on to study and paint the lost city. Karl Bryullov arrived at Pompeii in the 1820s, less than a century after the excavation started. He was so impressed by the remains of Pompeii that he almost immediately planned the new monumental painting that would make him an internationally recognized master. The Last Day of Pompeii shifted the focus from the natural disaster to human tragedy.

Many of the painter’s characters were real: Bryullov saw them at the already-functioning museum as imprints of bodies in solidified ash. Those included figures of a mother and her daughters in the left corner of the canvas and a woman who fell from her chariot. Pliny the Younger was there as well—in the right corner, he desperately begs his sick mother to leave the city with him.

Archaeologists from various countries have worked in Pompeii for centuries, which, paradoxically, created a lot of obstacles for their present-day colleagues. The standards of archaeology and preservation were radically different in the nineteenth century. Thus, a large part of the city’s treasures disappeared in private hands. Some city structures were disassembled or even accidentally destroyed. Moreover, tourists and researchers of various eras left their marks in the form of forgotten belongings or even graffiti. Still, despite centuries of work, the city excavation is far from over. Only recently, in July 2024, archaeologists made another discovery—a shrine painted vibrant blue, which was a rather rare tone for such an extensive use.

Could There Be Another Explosion?

The Pompeii landscape is ever-changing—not only because of constant human presence and overtourism but also due to the same forces that made this place so famous. All these centuries, Mount Vesuvius did not cease its activity, occasionally erupting and causing more damage. Unlike another famous Italian volcano, Etna, which erupts often and mostly brings little to no harm, Vesuvius is known to save its effort for truly devastating attacks. Since the eruption of 79 CE, it has exploded forty times, with the latest disaster occurring in 1944. Some superstitious locals believe that eruptions occur during other disasters happening in the human world, like World War II or the collapse of the Roman Empire.

Scientists observing volcanic activity believe that major explosions like the one that buried Pompeii only happen once every several thousand years. Still, the possibility of a minor eruption is present and could threaten a densely populated urban area around the volcano. Although today Vesuvius is considered to be rather safe, the local authorities monitor its activity and constantly update emergency evacuation plans.