There are many ways that philosophy can be communicated. Here we look at some of the most common vehicles for philosophical expression. We begin with what will be the most familiar, the philosophical essay. After that, we look at some of the more creative ways philosophers can communicate their ideas, including the thought experiment, dialogues, and aphorisms. The goal is to be able to make a distinction between literary philosophy and philosophical literature. The former is closer to dialogue and thought experiment, the latter to aphorism.

The Philosophical Essay

The first person to sit down and write an essay was the French thinker Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592). More accurately, he was the first to call this type of writing and thinking an ‘essay’.

In English, the French word ‘essayer’ means ‘to try’ or ‘to attempt’ something. Accordingly, when a philosopher chooses to write an essay, what they are doing is attempting something. This could be attempting to convince readers that something is or is not the case. Of course, it is not just philosophers who write essays, but it is philosophy that we are interested in here. All essays, in all disciplines, are, at their very core, attempts to understand and communicate something.

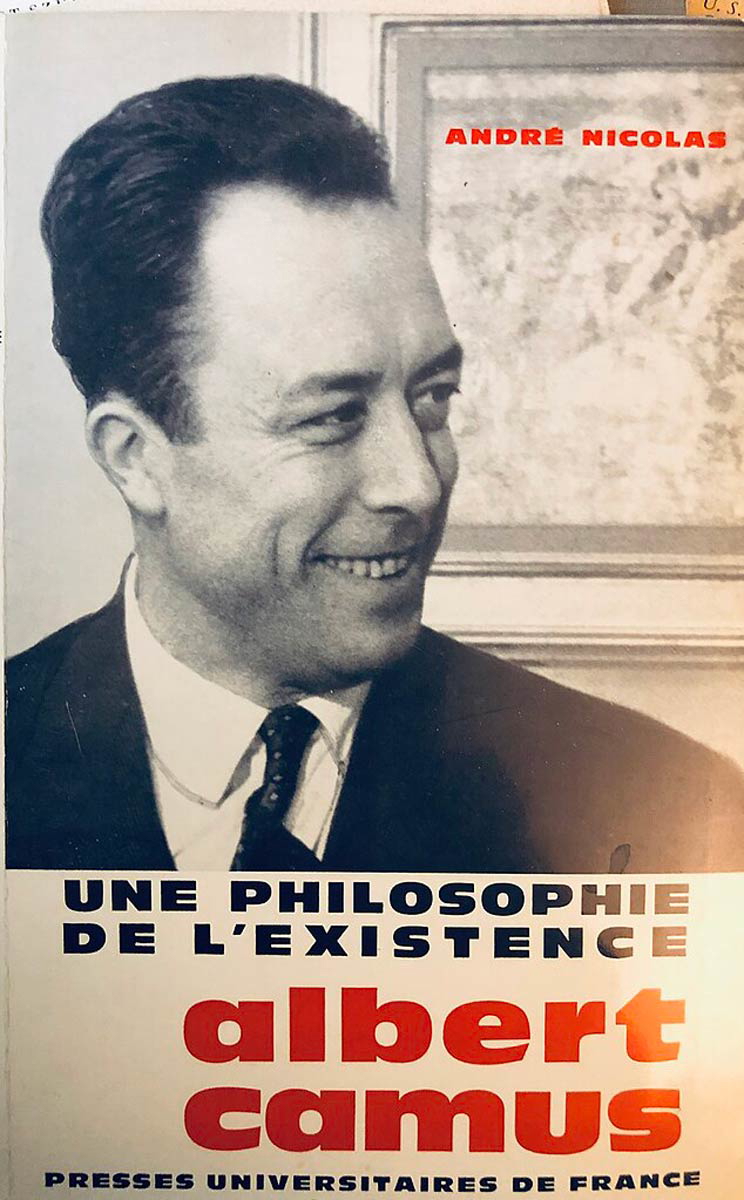

In philosophy as we know it today, essays typically appear in three forms: in academic journals, in edited collections, and as book-length works. Journals are published regularly, with editions coming out at regular intervals. Journals can be very broad and publish essays on all kinds of philosophy, but they can also have a very narrow focus, such as essays on the work of a particular philosopher. Edited collections are also typically focused on a particular subject area, but unlike journals, are not published regularly. In addition, the contributors are usually invited to submit their essays by the editor, whereas journals typically have blind submissions. Book-length essays are exactly that: they are published as standalone books and are often sold in bookstores. Albert Camus’s texts The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel are both book-length essays.

In the modern age, thanks to advances in technology, how essays are published and for whom is changing rapidly. Essays are published online (the one you are currently reading, for example) and even delivered as spoken pieces on podcasts or filmed as YouTube videos.

Thought Experiments

Academic essays use thought experiments—hypothetical situations created to test our intuitions. One of the things the creator of a thought experiment is trying to do is avoid any biases or prejudices readers might bring with them to a particular problem. For example, if the topic of inquiry is, say, abortion, readers might have such entrenched positions that as soon as they discover what is at issue, they refuse to consider the subject outside of their preconceived notions.

Judith Jarvis Thomson (1929-2020), in her 1971 essay “A Defence of Abortion,” created a famous thought experiment involving a ‘famous unconscious violinist’. She asks her readers to imagine that they wake up one day to discover they are in a hospital room attached by tubes to a world-famous violinist. He has an extremely rare problem with his kidneys and will die unless he is kept alive by someone whose kidneys match his own. You are the only match.

A ‘Society of Music Lovers’ has tracked you down and hooked you up to the violinist. Here is the kicker: if you choose to stay in the hospital attached to this man for nine months, he will become strong enough to survive on his own; however, if you pull out the tubes attaching you to him, he will die.

Thomson uses the thought experiment to show that while it may be a kindness for you to choose to allow the violinist the use of your kidneys, you are not obligated to do so. He has a right to life, but not a right to use your body. By detaching yourself, you do not deprive him of the right to life, but of the use of your body. There are obvious parallels to pregnancy and the use of a woman’s body.

Philosophical Dialogues

Philosophical dialogues resemble play—there are characters and a set scene. The most famous philosophical dialogist must be Plato (c. 428-348 BC). He is credited with writing thirty-five dialogues, with most involving his former teacher, Socrates. In fact, most of what we know about Socrates and his philosophy comes from Plato’s dialogues.

Why did Plato choose to write dialogues? One possible answer is that Socrates disapproved of written philosophy. In Phaedrus, one of Plato’s dialogues, we hear Socrates say that, unlike conversation, which is ‘living and breathing’, written words are final and dead. In addition, Socrates worries that written philosophy would lead to the death of argument and become simply about memorizing texts. By presenting Socrates’s philosophy in conversational, dialogical form, Plato avoids these problems.

Plato was not the only philosopher to use dialogues to express his ideas. Bishop George Berkeley (1685-1753) published his Three Dialogues in 1716. These dialogues take place between two characters called Hylas and Philonous. The first begins early one morning. Philonous is surprised to see Hylas up and about so early. Hylas says that he is so preoccupied by a conversation from the previous evening that he cannot sleep. He asks Hylas if he minds discussing the issues raised because he finds that talking ideas over with someone else makes them easier to understand.

Of course, we get to ‘eavesdrop’ on their conversation and pick up Berkeley’s ideas for ourselves. The first dialogue ends when they hear the college bell. They agree to meet the following morning, which introduces the second dialogue. The same goes for the third and final dialogue.

Berkeley uses the dialogic form to communicate his belief that material substance does not exist. This view he gives to his character Philonous. Hylas is incredulous that Philonous would propound such a bizarre notion.

Philosophical Aphorisms

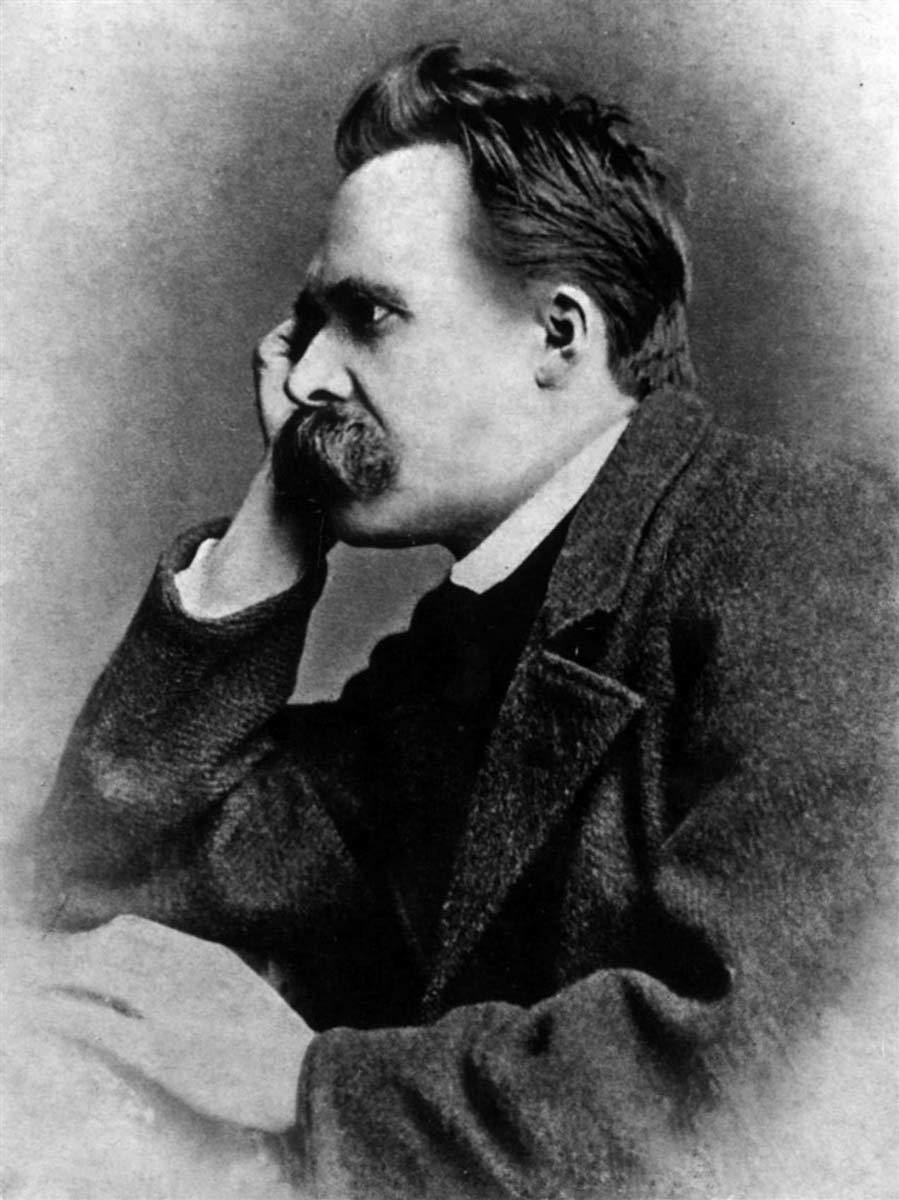

Aphorisms are short expressions of some perceived truth that require interpretation by the reader. An aphorism can be a single sentence or several pages long. Some philosophers are particularly known for their aphorisms. Two well-known examples are Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) and Blaise Pascal (1623-1662).

One famous example from the former is: “That which does not kill me, makes me stronger.” This idea will be familiar to most, but perhaps they do not know it’s Nietzsche. The line appears in his text Twilight of the Idols (1889). In one section of the text, Nietzsche groups forty-four short aphorisms under the heading: ‘Maxims and Missiles’ (Sprüche und Pfeile). This aphorism is number eight.

While individual aphorisms typically focus on a single idea for the reader to interpret, several aphorisms on a theme can be grouped together. Here, the author wants us to take in many different ideas on the same theme.

Sometimes, short extracts from longer aphorisms are taken and become standalone thoughts. For example, from Pascal we have: “All men’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone.” This is taken from a longer aphorism in Pascal’s posthumously published text Pensées (1670).

Philosophers have their reasons for writing in aphoristic form. Sometimes it is purely practical. Nietzsche, who had problems with his vision and suffered terrible headaches, found it easier to write in aphorisms. However, he also wanted to present his readers with ideas that they had to interpret for themselves. One of his most famous aphorisms comes from his Gay Science. Aphorism asks the reader what it would take for them to long for nothing more ardently than for time to endlessly repeat itself. The fact that this aphorism has caused so much controversy in philosophy demonstrates the power of the form.

Philosophical Literature

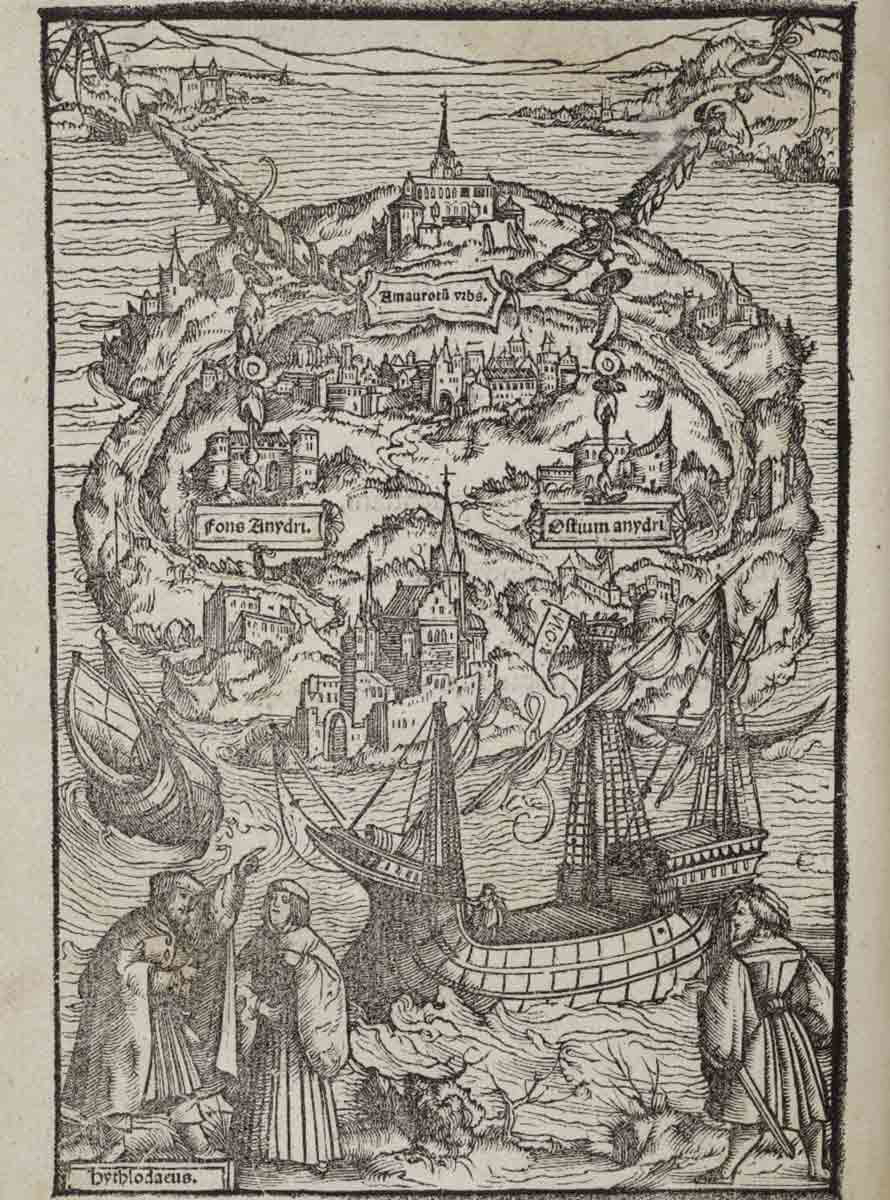

In 1516, Thomas More published Utopia. Within the pages of this short book, More presents a fictional island that is what he considered a perfect state. More used his book as a criticism of how society around him was run for the benefit of the rich. Some of the views expressed within would not be welcome in very many places today. For example, More allows the practice of slavery in his utopia.

A more modern critique of society, as well as the manipulative use of language, is found in George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). Many of the phrases found in both these novels have found their way into the English language to express political ideas. From Animal Farm, we get the expression, “… but some animals are more equal than others.” This is uttered whenever someone suspects preferential treatment by the government for people or groups.

The phrase comes from an amendment to the animals’ seventh commandment: ‘All animals are equal.’ Nineteen Eighty-Four has given us a whole host of terms, including ‘doublespeak’ and ‘thought crime’. Indeed, the term ‘Orwellian’ now refers to the idea of a situation being dangerous to a free and open society.

Philosophical literature is closer to thought experiments and dialogues. The ideas contained within these works of literature have already been thought out by the authors. They are then expressed in literary form. Aphorisms require far more interpretation and are usually not presented as closed and finished ideas.

Literary Philosophy

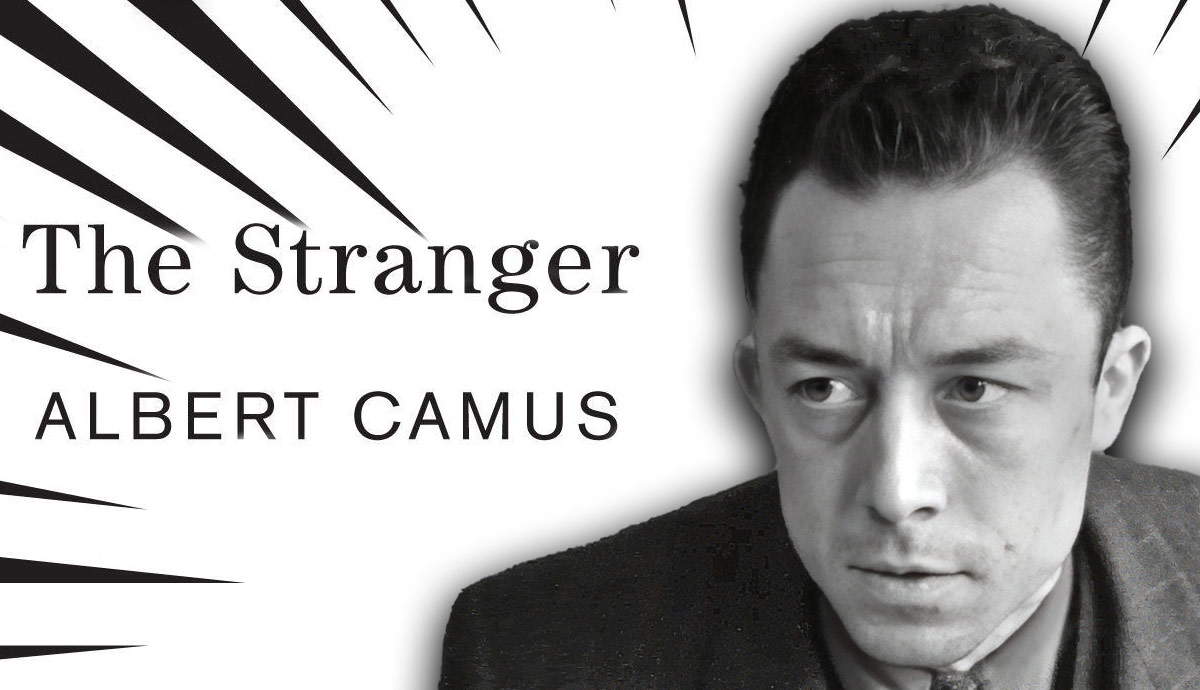

We can make a distinction between philosophical literature and literary philosophy in the following way. In the case of the former, the author presents philosophical ideas in their writing; whereas in the latter case, the author is philosophizing through the act of writing. That is, with literary philosophy, the author explores philosophical ideas through the narrative they create.

When we attempt to tackle philosophical fiction, knowing whether we have philosophical literature or literary philosophy will help us understand how to approach the work.

With his short novel The Stranger (1942), Albert Camus explores the idea of living in a modern society without committing oneself to anything one does not know for sure is the case. The novel itself is the product of a previous experiment, A Happy Death. Camus abandoned this novel (which was published posthumously in 1971) because he failed to find the answers he was looking for. In other words, the book did not work. When literary philosophy works, the novel becomes the starting point for the reader’s own philosophising. The idea is that when the reader engages with The Stranger, she ‘lives’ the philosophy for herself and through her interpretation, she contributes her own philosophy.

Friedrich Nietzsche does something similar with his Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-1892). Here, the literature is designed to induce a kind of revelatory experience in its readers that is similar to that experienced by Nietzsche earlier in his life. The idea is that the reader and author achieve a rapport after which philosophical issues can be explored ‘together’.

Unlike essays and philosophical literature, the finished product with literary philosophy is not the author’s final word on the subject but rather an invitation to others to contribute their own interpretations. Understood this way, literary philosophy is closer to what aphorisms hope to achieve.