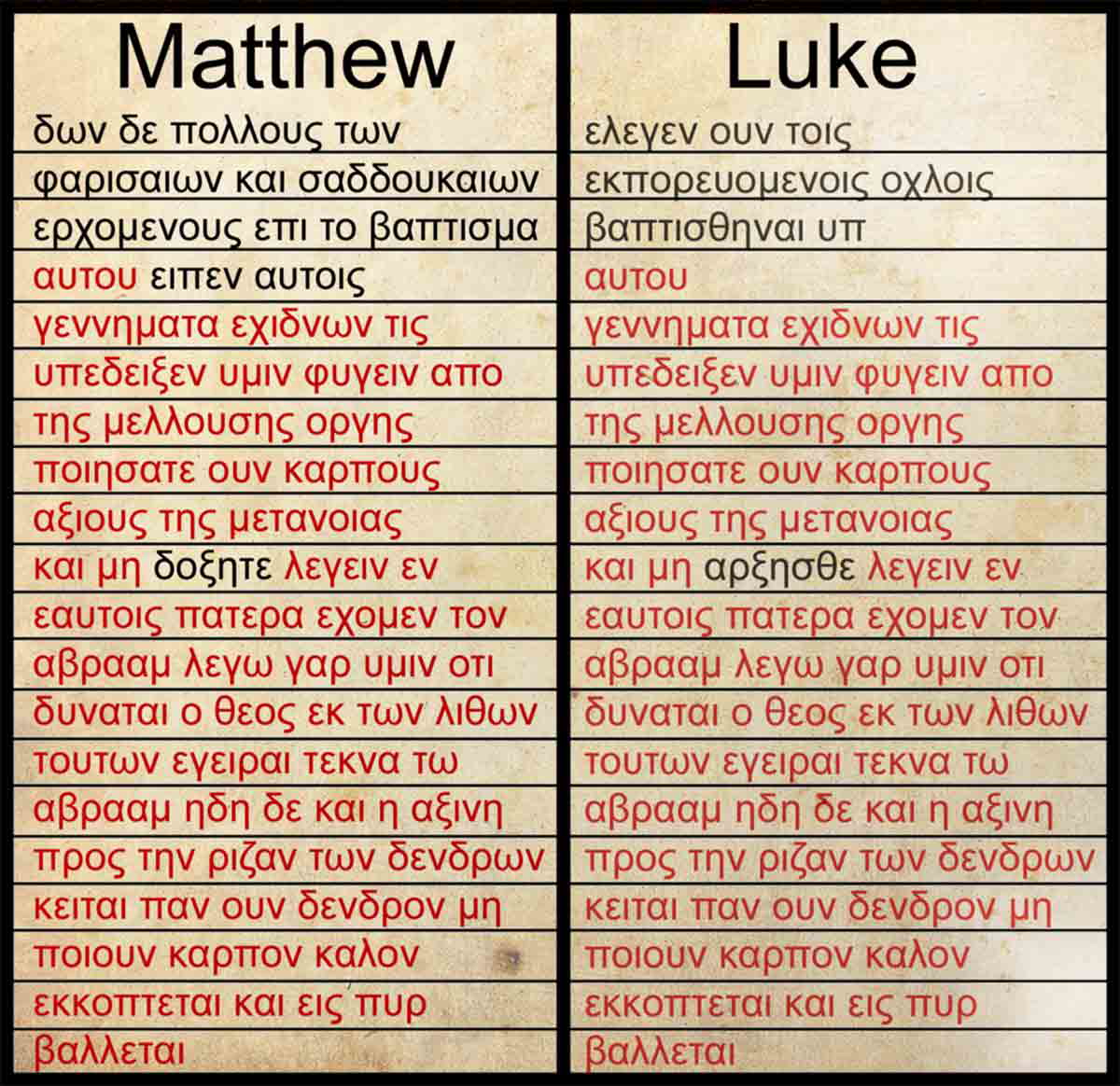

Readers of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John have long noted that there is some overlap in their content as they tell similar stories about Jesus. However, those stories sometimes differ in their telling. Some critics suggest that this renders the Gospels unreliable. Yet a number of scholars assert that many of the differences are understandable, explainable, and acceptable simply because ancient historians wrote according to rules that differ vastly from those governing how historians do their job today.

Are There Contradictions in the Gospels?

Some people refer to the discrepancies between the Gospels as contradictions. However, this is a misnomer. The law of non-contradiction states that something cannot be one thing and its opposite at the same time. For example, if I say that Lassie is a dog and Lassie is not a dog, then I am creating a contradiction, which makes the statement confusing, absurd, and totally impossible. We do not find such a contradiction in the Gospels. When one account mentions several women at the tomb of Jesus and another speaks of only one, that does not constitute a contradiction, as some have claimed. It is a difference, yes, but it does not break the law of non-contradiction.

So why are there differences? For example:

- Why does Mark’s gospel report that John and James asked Jesus for seats of honor, while Matthew says their mother asked on their behalf?

- Why does Matthew recount the story of Jesus healing one Gadarene demoniac while Mark and Luke talk about two?

- Why do the Gospels differ on the number of women present at the tomb of Christ?

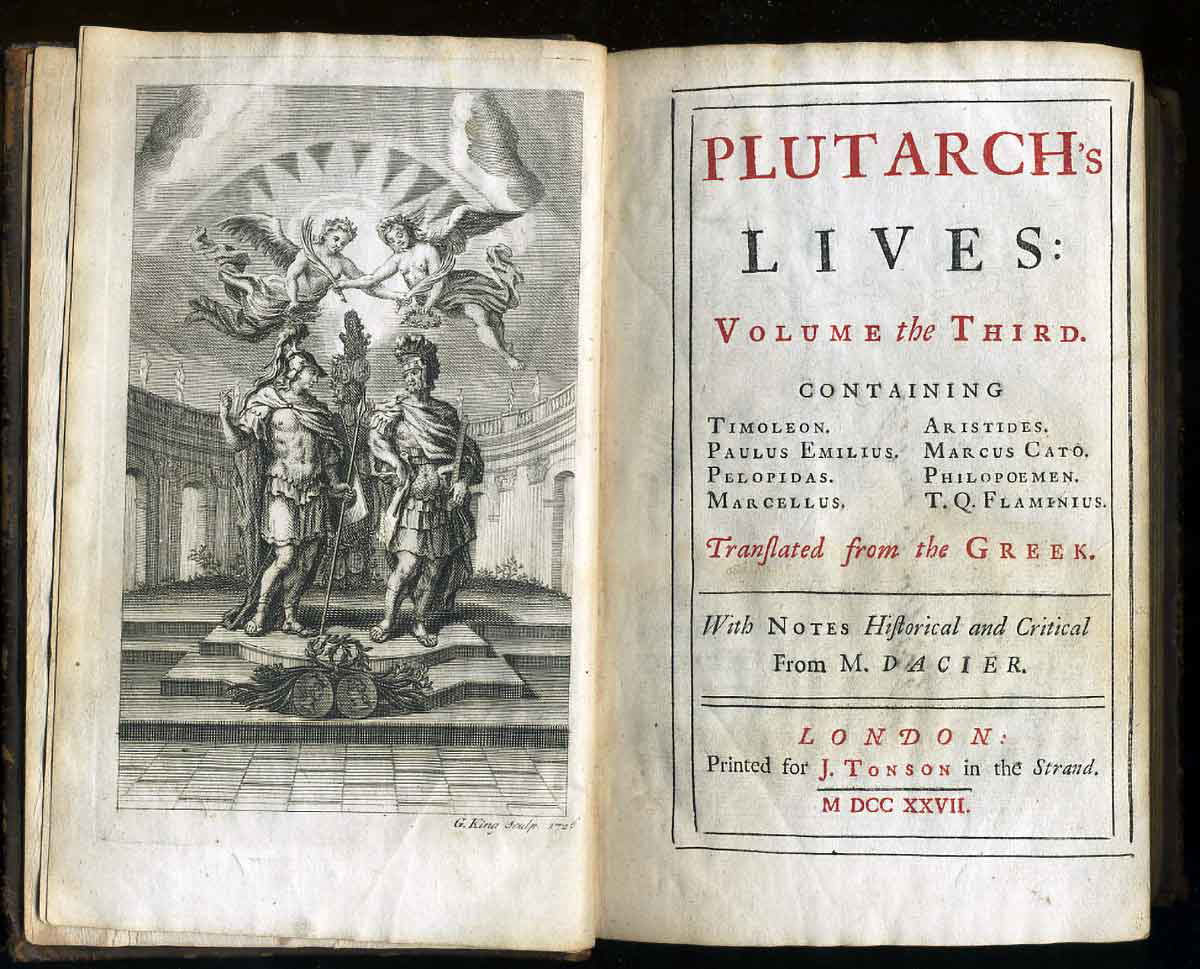

This is where the manner of writing biographies and reporting on historical events in the 1st century CE comes into play. Many scholars note that, when we look at ancient biographies, such as Plutarch’s Lives, we see that the authors employed a great many compositional devices and followed rhetorical principles that modern scholars do not use. This is true of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and these principles and devices account for many of the discrepancies in the Gospels, albeit not all.

The Art of Rhetoric

Rhetoric is defined as the art of speaking and writing effectively and persuasively. The ability to master and use rhetoric well was a highly-regarded skill in the ancient world and constituted a key element in the education of orators, writers, philosophers, historians, and scholars.

Aelius Theon was a teacher of rhetoric in Alexandria in the 1st-century CE. Very little is known about him, and he is often confused with a 4th-century grammarian named Theon, also of Alexandria. The earlier Theon wrote a primer entitled Progymnasmata that offered exercises for beginners to practice their writing skills. One of the lessons involved telling the same story in a variety of ways—as a conversation in one case or a paraphrase in another. He encouraged the use of chreiai, that is, brief sayings or anecdotes attributed to a specific person, used to make a point, reveal his character, or to teach a lesson.

Notably, he also taught that a narrative could be flexible. For example, when writing about someone’s speech, it was perfectly acceptable to reconstruct it as one wanted, as long as its content and tone reflected that of the orator.

Greco-Roman Biographies

Writers of biographies in the ancient world presented portraits of notable and noteworthy figures intended to inspire and edify readers to the extent that they would strive to emulate those great men. Unlike modern biographies, which generally start at the beginning of a person’s life and follow a chronological path, ancient biographies focused on a character’s words and deeds, often starting in the middle of a person’s life, presenting events not necessarily in the order in which they happened.

Authors included only the information that they considered important and did not pretend to be exhaustive in portraying a subject’s life. They also paraphrased a great deal of the material. All of this is true of the Gospels.

Additionally, writers of Greco-Roman biographies were more interested in accuracy than precision. Accuracy refers to how closely the account comes to what really happened and what really was said. Precision refers to all the tiny details of a person’s life or an event, or a given speech. Therefore, in recording the life of someone, it was the big issues that mattered and that had to be correct. The tiny details, for the most part, did not concern the writer. This is also true of the Gospels.

Plutarch’s Biographies

Plutarch’s Lives (also known as the Parallel Lives) provides excellent examples of Greco-Roman biography. Plutarch, born Mestrius Plutarchus in Chaeronea, Greece, prior to 45 CE, wrote more than 200 works, including 48 biographies of Roman and Greek figures. He used a great many compositional devices in portraying his subjects, devices such as transferal, displacement, conflation, spotlighting, simplification, telescoping, and story expansion and compression, all of which were used in ancient historiography.

What follows are examples of literary devices found in both Plutarch’s Lives and the Gospels. This is not an exhaustive list by any means. It serves only to make the point that the Gospels, in many ways, reflect the style of the standard ancient Greco-Roman biography.

Speeches

As noted above, Greco-Roman biographers rarely quoted speeches verbatim, but paraphrased them and, in some cases, made up speeches entirely, as long as the content and style fit that of the speaker about whom they were writing. This is certainly true of Plutarch. For the most part, he keeps the direct speech of a character short, only providing more lengthy conversations to reveal character, make a key point, and heighten the drama.

When it comes to speeches in the Gospels, readers are quick to note that some of those by Jesus are not identical in the different versions. For one thing, the direct speeches of Jesus in Matthew are much longer than they are in Luke. For example, Christ’s Sermon on the Mount is roughly 1,900 words long, while his Olivet Sermon is 1,500 in Matthew’s version. Luke, in his corresponding accounts, gives us only 550 words for the first and 450 for the latter. Some scholars suggest that this reveals the influence of Greco-Roman biographers like Plutarch on Luke, who chose to keep speeches short.

Of course, there may well have been a theological reason for Matthew’s choice, as theology and history are intertwined inextricably in the Gospels. The apostle was attempting to persuade a Jewish audience that Jesus was indeed the Messiah and wanted Christ’s own words to convince them. Hence, he offers long, detailed speeches from Jesus.

Chreiai

Ancient biographies included a great many utterances made by their subjects. In Plutarch’s Lives, we see this occurring over and over again. The most well-known are Caesar’s declarations that “the die is cast” when crossing the Rubicon and “I came, I saw, I conquered” when victory was complete.

The Gospels teem with chreiai as they quote Jesus time and time again. Consider the following well-known sayings recorded in the Gospels.

“Do to others as you would have them do to you” (Matthew 7:12).

“I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6).

“The truth will set you free” (John 8:32).

“My yoke is easy and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:30).

“For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to lay down his life for many” (Mark 10:45).

“I have come into the world as light so that whoever believes in me may not remain in darkness” (John 12:46).

These sayings tell us who Jesus was, why he came, and what he did. In a land where literacy was limited, these brief but pithy statements were easy to learn and remember.

Transferal

It is not uncommon in an ancient biography for the writer to purposely take the words or actions of one person and transfer them to another person. Plutarch did this many times. For example, in his Caesar, the general gives a rousing speech to his troops just prior to crossing the Rubicon. However, in Antony, Plutarch has Antony and Cassius deliver the pep talk.

We find such a transferal in scripture as well. In Mark 10:37, James and John ask Jesus for the privilege of sitting at his side in the kingdom of God. However, in Matthew 20:20-28, their mother approaches Jesus and makes the request. Some scholars suggest, by petitioning for this, John and James showed their personal ambition for greatness, which did not reflect positively on them. If their mother did it, it would be less damning for her sons.

Displacement

Displacement occurs when the author knowingly transplants an event from its place or time of origin to somewhere or sometime else. Plutarch does this often. For example, in Pompey, he tells the story of the disagreement between Caesar and Lucius Caecilius Metellus, a tribune, placing it before Caesar’s chase of Pompey to the city of Brundisium. However, in his life of Caesar, he places the dispute after Pompey has left Brundisium and Caesar has returned to Rome, which was the correct order of the events. Scholars suggest that authors made such changes for literary and stylistic reasons.

In the Gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke all place the events of the last week of Jesus’s life in a different order. The fact that the apostles wrote topically rather than chronologically speaks to the acceptance of changing the order of elements in a historical account. The content of each record remained the same, no matter the order of the events presented. Once again, it is the big picture that mattered to the Gospel-writers, and to them, a rearrangement of material did not alter the truth of their accounts.

Telescoping

Telescoping is similar to displacement as it involves collapsing events. This is most noticeable in Plutarch’s biography of Crassus, in which he skips over much of the man’s life to focus on the Parthian Campaign rather than Crassus himself.

In the Gospels, we see that collapsing events can involve changing the very time that an event took place, in the case of Christ’s crucifixion. Mark places it at nine a.m. on the morning after the Passover meal had been eaten. John, however, puts it just after noon, hours before the Passover meal took place. Scholars suggest that John did this for theological reasons. He wanted to emphasize that Jesus was the Passover lamb sacrificed for the sins of humankind and, therefore, took acceptable liberties with the material.

Conflation

At times, a writer may take two or more events and conflate them into one. Plutarch does this in his Cato Minor. He writes about two agrarian laws, one presented in January of 89 BCE and one presented in April of that same year. However, in his biographies of Pompey and Caesar, he conflates them, making it seem that both were present at the same time.

Mark employs conflation a great deal in his gospel. One simple example is that of the Gadarene demoniac. Matthew and Luke present Jesus’s interaction with two of them. Mark conflates the two interactions into one.

Spotlighting

This device refers to the choice of a writer to focus on only one individual. Obviously, with the majority of his Lives, Plutarch highlighted the subject of each biography. However, the main figure is not always the focal point. We see this in John’s Gospel where he names Mary Magdalene at the tomb of Jesus. The other Gospels mention other women, but none spotlight Mary Magdalene as John does. It may be that he chose to focus on Mary alone because it was she who ran and told Peter that the tomb was empty. He did not feel it necessary to name the other women, and, of course, just because he focused on one, it does not mean that the other women were not there with her.

Simplification Through Alteration, Omission, or Substitution

A writer may choose to omit details to make the telling less complicated and more understandable to the reader. They may also substitute one word for another for clarity. Authors may also leave out elements that they believe are unimportant.

We see an example of the latter in Plutarch’s biographies about Lucullus, a Roman general and statesman, and Cato Minor, a Roman senator. In the former, Plutarch reports that Lucullus was charged with keeping some of the spoils of the war with Mithridates and Tigranes won in 66 BCE. Cato spoke up for Lucullus, and the general won the case. Plutarch goes into great detail about the accusation and the outcome of the dispute. However, in his biography of Cato, he merely mentions it. This makes sense as Lucullus was at the center of the event while Cato was a figure on the periphery. Therefore, Plutarch omitted a great many details in his life of Cato Minor.

We see something similar in the descriptions of John the Baptist meeting Jesus for the first time. Whereas the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke go into great detail about John the Baptist and his relationship to Jesus, John has simplified the event and put his attention on Christ as the Son of God. This is not surprising as John’s focus right from the start of his book has been on Jesus as the Word that became flesh. Therefore, his reason for writing a different account rests in theology.

Expansion or Compression of Narrative Detail

Writers may choose to include many minor details to enhance the telling of a story, or they may compress the details into a shorter time frame. Plutarch does the latter in discussing Cato’s suggestion to hand Caesar over to the Germans. In the life of Caesar, the author says this took place in the year 55 BCE. However, in the life of Cato, Plutarch says the statement was made at the outbreak of a civil war in 49. Why? Scholars suggest that he wanted to link it with other attacks on Caesar that Cato had made earlier, thereby compressing the time between them.

In the Gospels, we see examples of both compression and expansion in the story of Jairus and his daughter, in which Mark puts in far greater detail than Matthew. Matthew compresses the story, cutting right to the chase with his statement that the man’s daughter was dead. He does not even give the man a name, but only refers to him as “a synagogue leader.” However, Mark expands the story as he gives more details about it. In his rendition, Jesus has longer dialogues with both Jairus, the girl’s father, as well as the mourners at the man’s home. He describes the people laughing at Jesus for saying she is only asleep. Interestingly, Mark, a Gentile, quotes Jesus as saying in Aramaic, “Talitha koum,” which means “little girl, I say to you, get up,” at which point she stands up and walks around. By not announcing at the start that the girl was dead and by adding longer discussions and more specific details, Mark creates a dramatic story which is typical of his writing style.

Paraphrasing

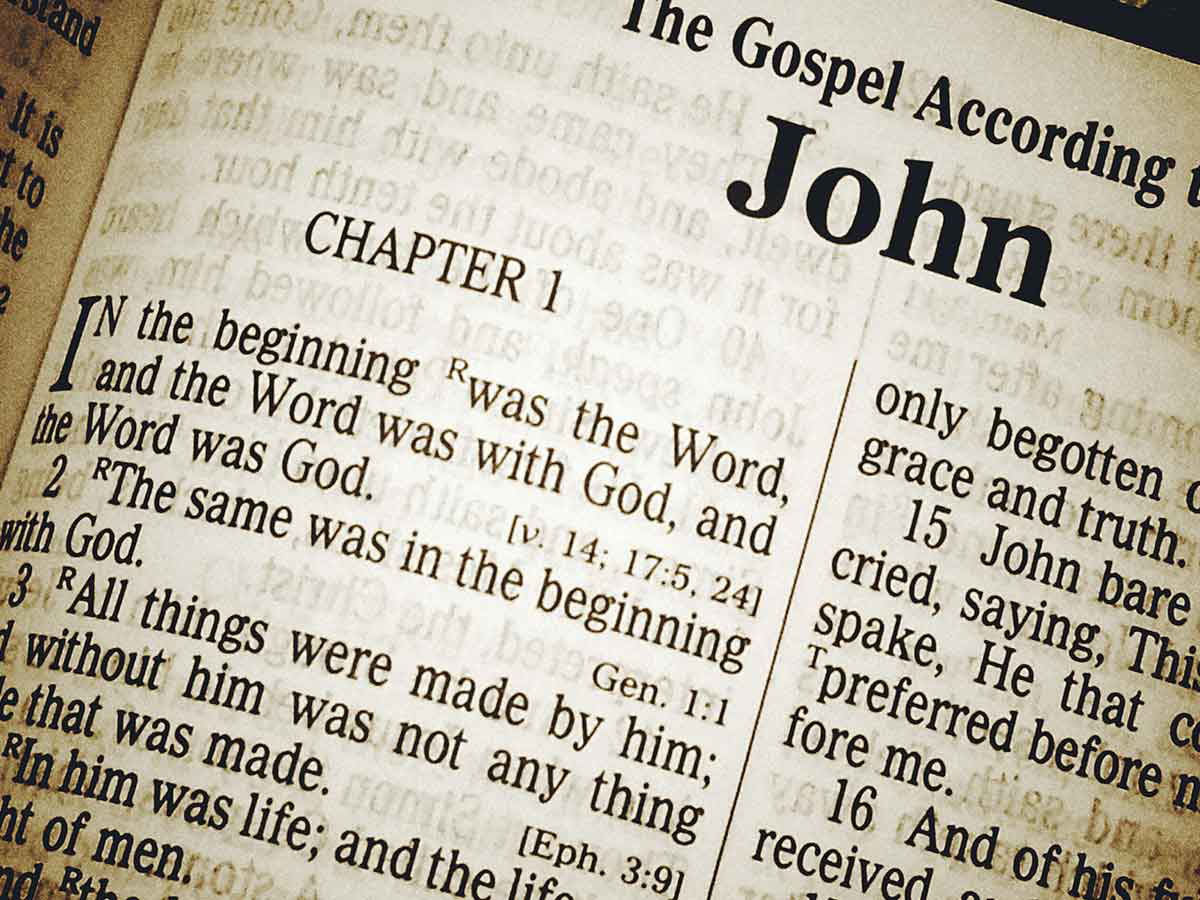

Writers often opt to tell a story in their own words. Plutarch’s Lives are riddled with paraphrases. In his biography of Cassius, for example, he provides no direct quotations from the man, but paraphrases everything. The gospel writers tended to paraphrase Old Testament passages in new and fresh ways. For example, John opens his Gospel with a statement that, in essence, echoes the opening of Genesis as he writes, “In the beginning was the Word…” Matthew paraphrased Isaiah 7:14 in verses 22 and 23 of his first chapter to indicate that Jesus was the fulfillment of the prophecy about the virgin birth.

The Role of the Holy Spirit

While paintings of an angel inspiring Matthew to write his Gospel abound, there is nothing in the Biblical text to indicate that such a heavenly being helped him with his task. Rather, Christians assert that it was the Holy Spirit, the Third Person of the Trinity, who led all authors of scripture to write their works.

Some critics suggest that, if this is the case, there should be no discrepancies of any kind within the texts. However, the Christian understanding of the process suggests that God did not dictate the words to the authors. Instead, he allowed for their own styles of writing and particular vocabularies to show up in their writing, along with the influences of other ancient historians.

Conclusion

It is unfair to judge the Gospels or any other ancient biography by the rules historians and biographers employ today. If we do so, then we practice what C.S. Lewis—philosopher, author, and Christian apologist—called chronological snobbery as we unjustly expect people in the past to think, believe, and write the way that we do in the 21st century. It is unlikely that the original audiences for the Gospels were perturbed by the differences in them that critics focus on today, differences that do not necessarily render the Gospels inaccurate and unreliable, as they offer the same information about who Jesus was and what he did. In other words, they present that big picture and do not sweat the small stuff.

Bibliography

- Bock, Darrell L. “Precision and Accuracy: Making Distinctions in the Cultural Context That Give Us Pause in Pitting the Gospels Against Each Other” in Do Historical Matters Matter to Faith? Editors: James K. Hoffmeier and Dennis R. Magary. (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway), 2012.

- Keener, Craig, Christobiography: Memory, History and the Reliability of the Gospels. (Eerdmans eBook), 2015.

- Kennedy, George A. “An Introduction to the Rhetoric of the Gospels”. Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. Vol. No. 2 (August, 1983).

- Licona, Michael R. Why Are There Differences in the Gospels? What We Can Learn From Ancient Biography. (Oxford University Press eBook), 2016.

- Pelling, C.B.R “Plutarch’s Adaptation of His Source Material”. The Journal of Hellenic Studies. Vol. 100, 1980..

- Plutarch. Lives: https://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/plutarch-s-parallel-lives