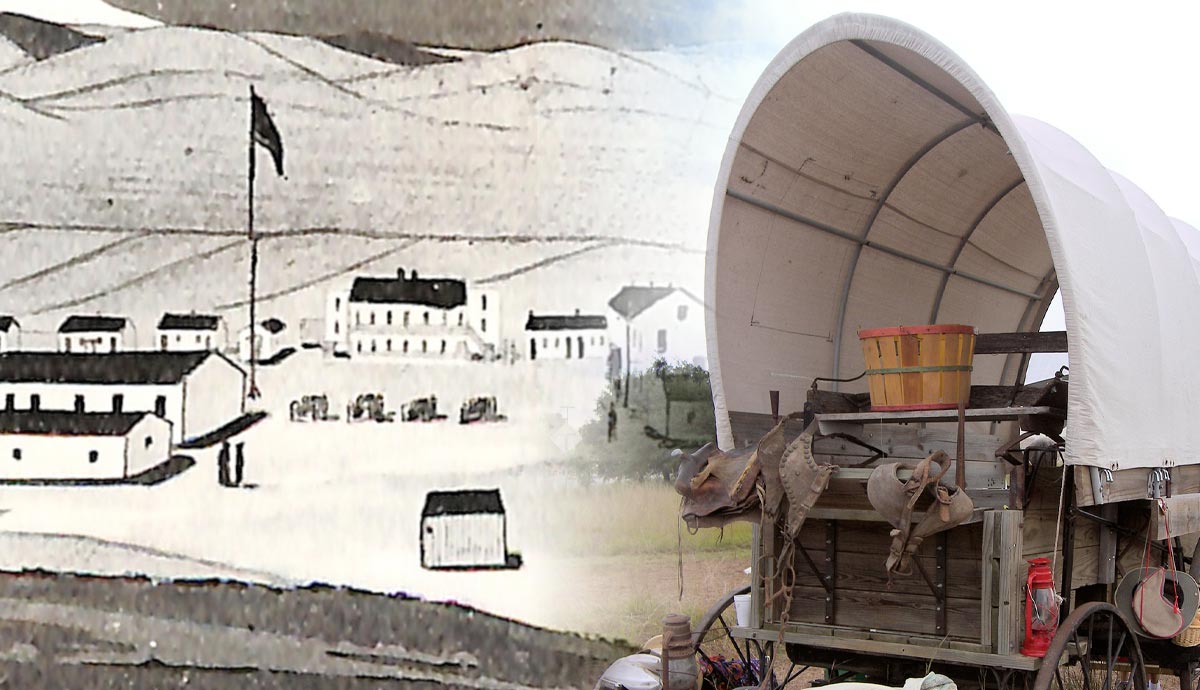

As Manifest Destiny rippled through America, the dream of moving west became a reality for many families. As thousands set out on a number of wagon routes, many were unprepared for the harsh reality that the journey soon confronted them with. Disease, tensions with Indigenous peoples, accidents, and the weather were just a few challenges that emigrants faced on their trips to a new life. Hundreds would die, and some would survive, but the wild tales of their adventures traveled to all corners of the country and persist in the depths of US history to this day.

1. An Utter Disaster

On September 8, 1860, a wagon train of eight wagons from Wisconsin and Illinois, led by Elijah Utter made its way along the South Alternate route of the Oregon Trail. As they traveled through Southwestern Idaho, the assemblage of forty-four emigrants, twenty-one of them children, made up of members from several family groups, was attacked by a contingency of Native Americans, numbering twenty-five to thirty. In a disaster that would become known as the Utter Massacre or the Snake River Massacre, the members of an unnamed “Indian” tribe attempted to stampede the wagon train’s herd of livestock, then attacked the emigrants themselves as they attempted to circle their wagons. After an initial feint, the Indigenous men appeared to back off, and the group continued onto a nearby river for desperately needed water. However, the group of attackers returned, and the train decided to leave some wagons and supplies in hopes that it would satisfy the assailants before moving on ahead to circle the wagons once again.

Still, the onslaught continued into the next day. Numerous emigrants were wounded and killed, including Elijah Utter and his family, who refused to leave their injured patriarch. The survivors elected to flee on foot, leaving their wagons and the majority of their supplies. The group moved down the Snake River for a week, then, exhausted, set up camp at the Owyhee River crossing in Oregon. There were eighteen children and seven adult survivors when they encamped.

Desperate, they ate two dogs, what waterfowl they could shoot, foraged for berries, and fished mussels from the river. Four children and one man died from starvation and wounds during the time at the camp, and it is believed that the survivors were driven to eat their flesh. A small group attempted to leave the camp in search of rescue. After they encountered a party of Native Americans, four children from that group were taken captive.

Their bodies were later recovered by US Army soldiers.

On October 24, an army expedition finally reached the Owyhee Camp, rescuing the ten survivors that remained. The events that the Utter wagon train was subjected to would gain notoriety as the largest disaster to befall travelers on the Oregon Trail. This event would further deteriorate the relationships between Indigenous people and the white settlers encroaching on their homelands. It is estimated that approximately 360 wagon train travelers were killed by Native Americans between 1840 and 1860—the era in which Utter and his ill-fated party traveled. Though estimates for Indigenous deaths are harder to come by, historians estimate the number of members from various tribes killed runs at more than 425 during the same historical period.

2. Almost 10% Were Killed by Disease

Gen-Xers and Millennials likely remember seeing “You have died of dysentery” flash across their computer screens as they played the iconic Oregon Trail video game. This fate wasn’t too far off the mark from reality. It is estimated that 6-10% of those heading west perished due to some form of illness along the way. With a journey of approximately 2,000 miles, this would mean there was an average of 10-15 deaths per mile of trail. Cholera, dysentery, measles, smallpox, and scurvy were some of the more common ailments afflicting travelers. Very few marked gravesites remain today, as burials were often hurried so the train could move on, or hidden to prevent grave robbing.

3. The Doomed Donners

The grisly story of the Donner Party is perhaps the most famous of tales to arise from the wagon train era. The twenty-wagon convoy made a series of bad decisions that resulted in their group being forced to a halt as winter weather descended on them. They became trapped near the Sierra Nevada mountain range, where members of the group starved, succumbed to disease, and were forced to eat anything they could find—including the dead—to survive. 87 started the trek from Illinois in April 1846, but almost half would die before rescue.

4. Emigrants Ditched Their Stuff to Survive

Travelers along the western trails were advised to pack everything they would need to sustain their families for six months. Besides food and provisions, the settlers would need emergency equipment, tools for wagon repair, and items for their livestock. In addition, many travelers wanted to bring their most treasured possessions with them as they began their new lives out west. This often resulted in overpacking and heavily laden wagons. This could be problematic, as the draft animals used to pull the loads could only handle so much. As a result, many were forced to discard items not necessary for immediate survival along their route. One traveler dubbed Fort Laramie, in present-day Wyoming, “Fort Sacrifice” because of all of the goods left behind there. In just the first six months of 1849, over 20,000 pounds of bacon had been dumped at the fort.

5. Prairie Madness Struck

In an era when mental illness was poorly understood, a phenomenon known as “prairie madness” or “prairie fever” made itself known among the pioneers heading west. This affliction caused sufferers to experience a mental break, which often led to periods of depression and violence. The conditions of high stress, fatigue, and illness on the trip created a perfect storm, especially for those already suffering from mental illness.

Perhaps the most well-known case of prairie madness was suffered by Elizabeth Markham in 1847. Her family was traveling to Oregon when she declared she would go no further. After arguing with his pregnant wife for a while, her husband, John, decided to continue, certain his wife would come to her senses and catch up. When she didn’t, he sent his oldest son back to retrieve his mother.

Eventually, Elizabeth returned, minus her son. She matter-of-factly told her husband she had beaten their son to death with a rock. John rushed back and found his son alive but returned to find his wife had set fire to one of their wagons. The family survived, including the baby Elizabeth later gave birth to in Oregon, and made it to the end of the trail. They had one more child before eventually divorcing.

6. Milk Sickness Strikes

A mysterious disease began attacking settlers beginning in the 1800s, afflicting many frontier families. Sufferers would suddenly be struck with vomiting, weakness, and trembling. Coma and death often followed the onset of symptoms. The disease got many nicknames, including “the slows” and “the staggers,” before it received its final moniker, “milk sickness.” Many travelers brought livestock, including milk cows, with them on the trip to provide nourishment on the trail. It turned out that a native plant, white snakeroot, was to blame. Cows that ingested the plant would pass toxins from the plant via their milk onto their unsuspecting owners. Though it has never been definitively proven, biologists believe that the plant compound tremetol was to blame for milk sickness.

7. “A Mournful Accident”

The unfortunately named John Shotwell made a name for himself on the Oregon Trail, but not in the way he likely hoped. Young Shotwell went down in history as the first person to die on the Oregon Trail from a firearm accident. On May 13, 1841, Shotwell reached into his wagon to pull out his rifle, likely to locate a meal. He pulled the gun out muzzle first, and in the act, it went off and lodged a bullet near his heart. He perished not long after. While shootings would become common along the trail west, they were usually attributed to accidents such as this one.

The prospect of a better life filled with opportunities was what drove the constant push westward. Despite the dangers and the reality of horror and misery, thousands of Americans braved the perils, fulfilling the belief of Manifest Destiny and spreading the influence of the United States.

This was a new chapter for the young nation, and one that spawned innumerable stories that shaped American identity.