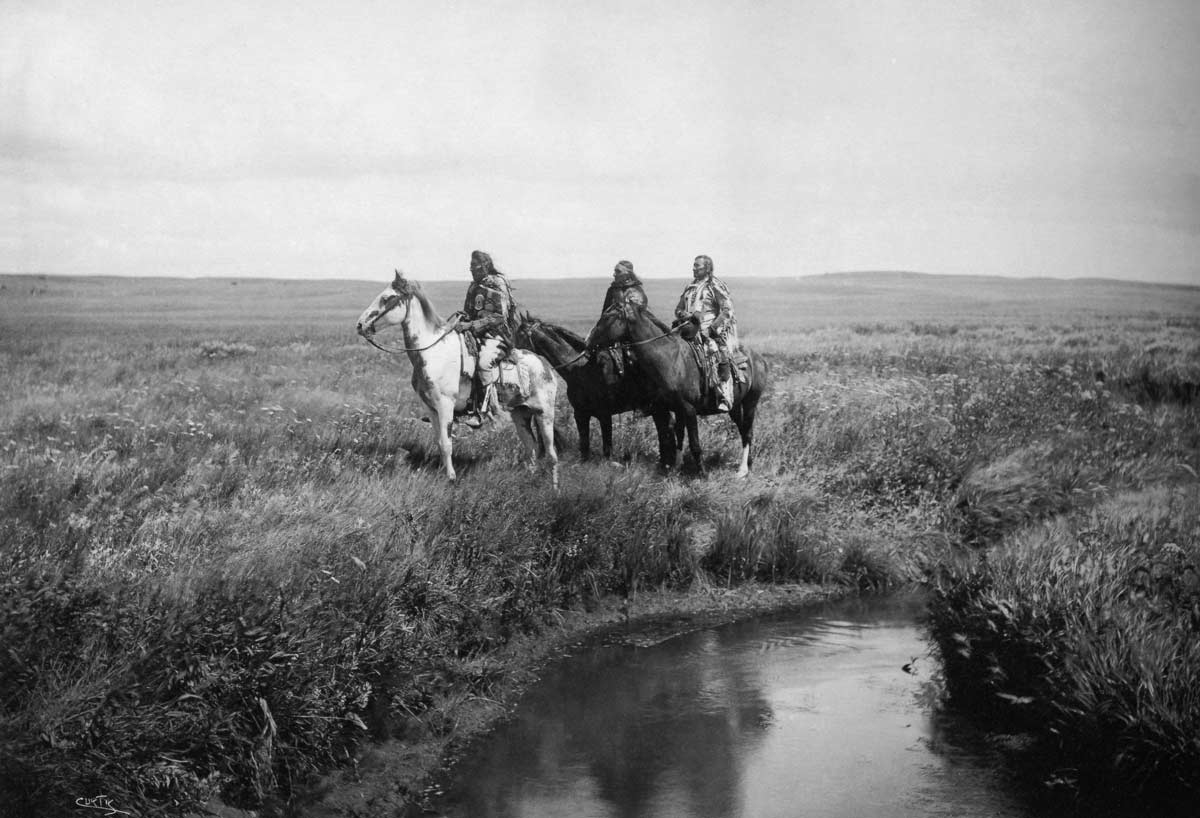

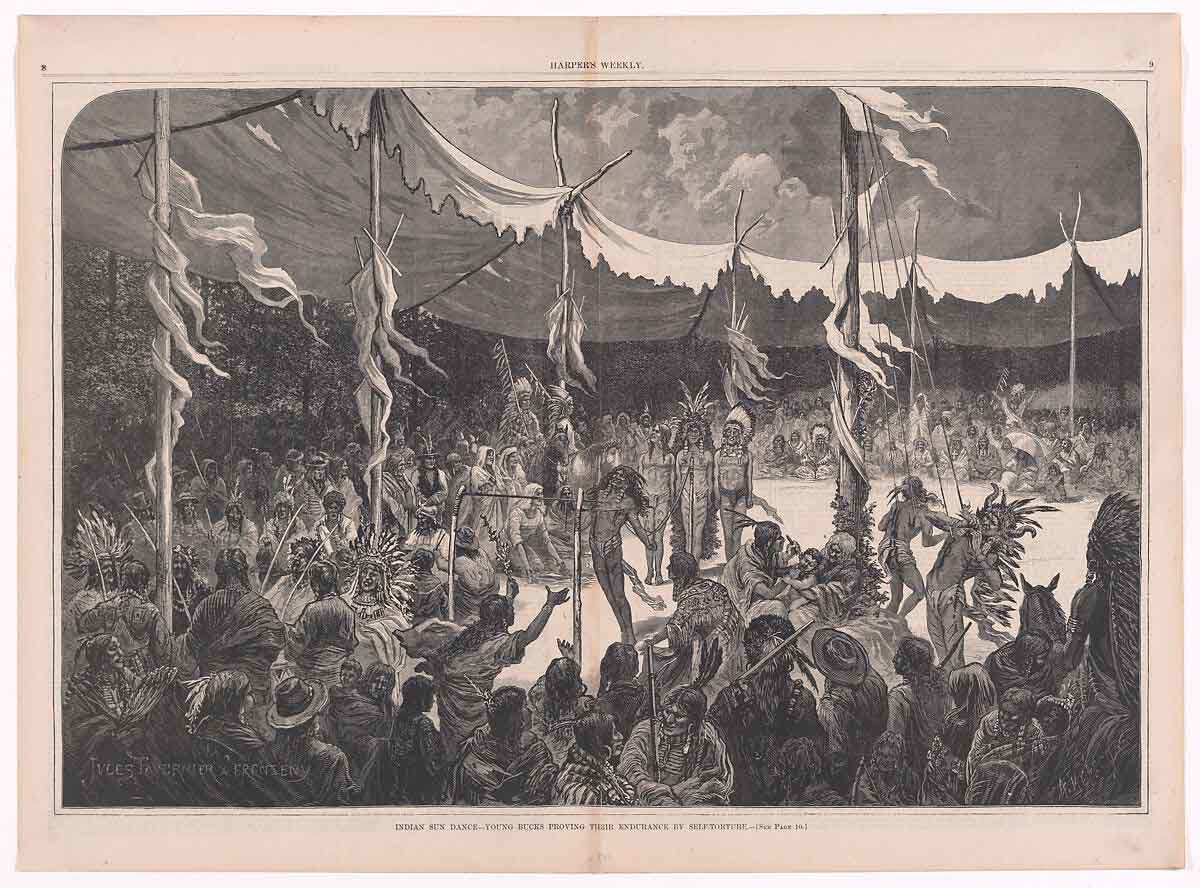

Long before the arrival of British traders, explorers, and surveyors, the First Nations of the Canadian Plains developed rich and complex cultures, deeply connected to the rhythms of their lands and the seasonal migrations of bison herds. The Blackfoot, for instance, were skilled hunters who used to drive bison over cliffs (the practice is now known as “bison jumping”). The Assiniboine preferred to pursue bison herds and drive them into traps (“pounds”), often thoughtfully obscured by natural features. Each year, the people of the Plains honored the ceremony known as the Sun and smoked their sacred pipestems to communicate with the supernatural. When the time was right, they would pack their tipis and travel freely across the Plains.

Plains or Prairies?

The Canadian Plains, nestled between the Western Cordillera and the Canadian Shield, are one of the seven physiographic regions that make up Canada. In addition to the aforementioned Cordillera and Canadian Shield, the other regions are the Hudson Bay Lowlands (a sedimentary basin in the middle of the Canadian Shield, south of Hudson, and James Bays); the St. Lawrence Lowlands (the smallest of the seven regions and the most densely populated, lying between the Canadian Shield and the Appalachian region); and the Appalachian Region (bordering the Atlantic Ocean, the St. Lawrence Lowlands to the south and the Canadian Shield to the northwest). Finally, the Arctic Lands lie north of the Arctic Circle.

Altogether, the Plains (or Great Plains) occupy a huge area of approximately 2,900,000 square km (1,125,000 square miles) across Canada and the United States, comprising 18 percent of Canada’s land surface.

The Canadian Plains extend up from the U.S. border across southwestern Manitoba and the southern portions of Alberta and Saskatchewan, from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the forests of southeastern Manitoba in the east. They include part of the Saskatchewan River and the Qu’Appelle River. It is along these rivers that most of the region’s trees grow. High grasses (or tall grasses) blanket the plains in the east. To the west, the land is mainly covered with short grasses, cacti, and sage.

The so-called Southern Alberta Uplands, a region of isolated plateaus rising steeply above the surrounding expanse of plains and lowlands, represent a buffer zone between the plains and the mountains.

Immediately south of the Saskatchewan River begins the broad swath of aspen parklands that stretches across Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, and marks the transition from lowland to subarctic region, from prairie to boreal forest.

The Plains are part of a larger region called the Canadian Prairies (or simply the Prairies). In fact, Manitoba, Alberta, and Saskatchewan are also known as the Prairie Provinces. The Canadian Plains represents a cultural area rather than a region defined by fixed borders. First Nations such as the Blackfoot, the Cree, Assiniboine, Dakota, and Stoney are an integral part of the history of this area.

As McMillan and Yellowhorn beautifully write, “Although Plains cultures were dynamic, the equestrian warrior with the feather headdress is the stereotypical image that has been immortalized in frontier lore, Western movies, novels, and motorcycles.” Yet this remains a purely Western stereotype, as we shall see in this article.

The Blackfoot Confederacy

At the height of their power, the Blackfoot Confederacy (or Blackfoot Nation) was the main Indigenous political entity across the northwestern Plains. It comprised three nations, the Siksika (literally “black foot”), the Piikani (or Peigan, “scabby robes”), and Kainai (or Blood, meaning “many chiefs”). All these tribes refer to themselves as Siksikaitsitapi, “Blackfoot-speaking real people,” or Niitsitapi, meaning “the Real People.”

Despite remaining three separate political entities, the Piikani, Siksika, and Kainai shared the same language (part of the Algonquian linguistic group) with only a few linguistic variations in dialect, and they often camped, fought, and hunted bison together. The Confederacy also included two smaller nations, the Athabaskan Tsuut’ina Nation (known among the Blackfoot as Sarcee) and the Algonquian-speaking Gros Ventre (or Atsina). The Blackfoot call their ancestral lands Niitsitpiis-stahkoii, which translates as “the Land of the Original People.”

Their territory encompasses parts of southern Saskatchewan and Alberta and the northern portion of Montana in the United States. It stretches from the Rocky Mountains to the border between Alberta and Saskatchewan, east of Cypress Hills and along the South Saskatchewan River, and from the North Saskatchewan River to the Yellowstone River across the border with the United States. Present-day Edmonton, in Alberta, is built on Blackfoot lands.

Unlike other Plains people, the Blackfoot were known to cultivate small plots of tobacco. They also were the least involved in (and affected by) the fur trade. On September 22, 1877, the Blackfoot signed Treaty 7, the last of the Numbered Treaties made between the First Nations of the Plains and the Canadian Government. This was also the last major watershed moment in their history, marking the beginning of the so-called Reserve Era for the Siksika, Piikani, Kainai, Tsuut’ina, and Sarcee.

The Siksika, Kainai, and some Piikani groups settled on reserves in southern Alberta. The Siksika today occupy a reserve, called Siksika 146, about 80 km (50 miles) east of Calgary, along the Bow River, close to where the Blackfoot Crossing Fortified Village (also known as Cluny site) lies.

Many Kainai inhabit the Blood 148 reserve, west of Lethbridge, along the Belly River. Most of the Piikani (also known as the Piikani’s southern division) went to live on the Blackfeet Reservation in northern Montana, while many of the Piikani northern division settled down on the Piikani 147 reserve (formerly Peigan 147).

Before and after the arrival of Europeans, during the Dog and Horse Days, the Blackfoot were known among other First Nations as fierce warriors. Their sworn enemies were the Plains Cree and Ojibwa, as well as the Siouan Assiniboine, close allies of the Plains Cree, and the Ktunaxa (Kutenai), the ancestral custodians of much of southeastern British Columbia.

In both times of peace and war, the Blackfoot placed the corpses of their deceased on trees or scaffolding. Sometimes they would shoot the deceased’s favorite horse and lay it next to the corpse, to accompany its owner into the spirit world, whose entrance, according to the Blackfoot, was located at Sand Hills.

McMillan and Yellowhorn beautifully write that beyond Sand Hills, the Blackfoot “imagined a pleasant country where their ancestors lived and practised customs much as they had in life. It was a wondrous place to behold, but it was guarded by a fearsome giant bison, which only let in the souls of dead people. Sometimes if a person was injured seriously and their souls wandered too close to the Sand Hills, the giant bison would sense their life and chase them back to their bodies.”

The Dakota

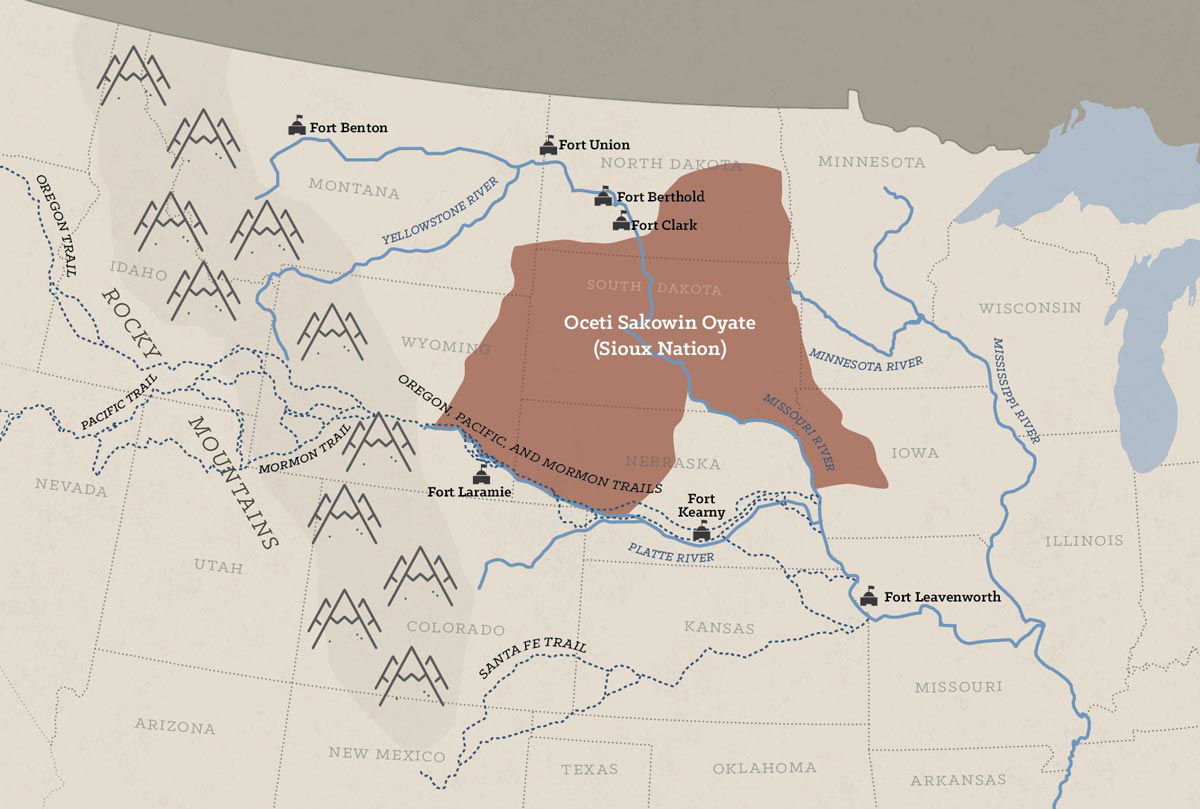

For centuries the Dakota people have been known by the name of Sioux, from a French abbreviation of Nadouessioux, the Ojibwa word for “snake” or “enemy.” The Dakota Nation is traditionally divided into three major groups. The eastern groups (or Eastern Dakotas) are collectively called the Santee Dakota. Before the 17th century, they lived in present-day Wisconsin and northern Minnesota on the shores of Lake Superior. The central group includes the Yankton and Yanktonai, collectively known by the endonym Wičhíyena. During the colonial period, they lived on the edge of the Plains. The western group comprises the Teton Lakota (also known as Teton Sioux).

For centuries, Dakota groups of hunters and warriors moved across the Plains into present-day Saskatchewan, often waging war against the Plains Ojibwa. But it was in the 1860s that “American” Dakota crossed the border with Canada, intending to stay and escape the brutal treatment they received from the Americans.

The Dakota migration happened in two major waves involving two different groups, the Santee first and the Teton Lakota later. In 1863, after the Battles of New Ulm (also known as Minnesota Uprising), some bands of Santee moved northwest into Manitoba, where they joined the Métis around Fort Garry. Others continued northwest, eventually settling in Saskatchewan.

The second major wave of migration occurred in 1876, as the direct consequence of the Battle of Little Big Horn. On April 29, 1868, the Lakota, led by their chief Sitting Bull (1831-1890), known in the Lakota language as Tatanka Iyotake, “Buffalo Bull Who Sits Down,” signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie with the American government. The Lakota agreed to relocate to the Black Hills, part of the Great Sioux Reservation, an area set aside by the U.S. Government for the Lakota, where they were promised to live “forever” in peace.

But then gold was discovered in the Black Hills. The year was 1874. The Treaty was broken. The Lakota waged war against the Americans. Together with the Cheyenne, they annihilated the 7th Cavalry officers led by George Armstrong Custer (1839-1876) at Little Big Horn, between June 25 and 26, 1876. Despite this historic victory, however, in 1876, three thousand Teton Lakota moved into southwestern Saskatchewan, encamping around the Cypress Hills and Wood Mountain. Sitting Bull soon joined them.

For decades, the Canadian government has considered the Lakota and Santee “American refugees” and consistently failed to recognize them as “Aboriginal peoples of Canada.” In July 2024, the government formally apologized for denying them their basic human rights.

The Assiniboine and Stoney

Based on their language, a dialect of the Dakota language, the Assiniboine are believed to be a splinter group of the Dakota who moved north into Canada at some time before 1640, when they were mentioned in the Jesuit Relations. In the mid-17th century, the Assiniboine were known to occupy the region around Lake Winnipeg and Lake of the Woods, but then, after the fur trade began, they spread westward into present-day Alberta, Montana, and Saskatchewan. Here they adopted the Plains culture, becoming bison hunters and warriors, building bison pounds to trap bison, and using travois to carry their tipis and goods during their seasonal migrations.

Large-scale bison hunts were usually led by a special leader called the “hunting chief.” In addition to bison, they also hunted moose, elk, and deer. Their main allies were the Plains Cree and Ojibwa.

Together with them, they repeatedly waged war against the nations of the Blackfoot Confederacy and the Dakota in the south. The Stoney Nakoda are believed to be a splinter group of the Assiniboine. The term they chose for themselves, Nakoda (or Nakota), is a reminder of their connection to the Dakota, the nation from which both the Stoney and Assiniboine originated. In fact, the central Dakota groups spoke a dialect of the Dakota language that substituted the letter “d” with “n.” Hence “Nakoda” instead of “Dakoda” or “Dakota.”

At some point during the 18th century, the Stoney pushed west into the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in present-day Alberta, where they clashed with the Blackfoot Confederacy. The Stoney, however, maintain that their ancestors have continuously inhabited the Rocky Mountain foothills, from the headwaters of the Athabasca River to Chief Mountain in present-day Montana, since time immemorial.

In the late 18th century, the Stoney became involved in the fur trade, working as guides for surveyors of the Canadian Pacific Railway and Geological Survey of Canada, as well as for various explorers. After the signing of Treaty 7, groups of Stoney settled on six reserves across western Alberta, not far from Calgary and the British Columbia border. In 1970, American filmmaker Arthur Penn shot his famous western film Little Big Man, starring Dustin Hoffman, Chief Dan George, and Faye Dunaway, on the Stoney 142, 143, 144 Reserve at Morley, between Calgary and Banff.

The Plains Cree and Ojibwa

The Cree and Ojibwa arrived in the Plains relatively recently. The Plains Cree prefer to call themselves paskwâwiyiniwak or nehiyawak. The suffix –iyiniwak, meaning “people,” is used to differentiate between Cree bands from various regions across Canada. The Cree Nation has, in fact, the widest geographic distribution than any other First Nation in present-day Canada.

In the 18th century, groups of Cree moved westward into the Plains from their lands in the Great Lakes region, northern Quebec, and the Hudson Bay area. They eventually settled in the parkland areas along the eastern and northern parts of the Plains, preferring forests to open prairies, and becoming what Western historiography has since called “the Plains Cree.”

Unlike the Blackfoot, the daily lives of the Cree largely depended on the fur trade. Backed by their faithful allies, the Assiniboine, they often acted as intermediaries between Western tribes and fur traders.

While the Blackfoot typically hunted bison by driving them off cliffs, the Plains Cree mainly used pounds to intercept bison herds. Explorer, journalist, and professor Henry Youle Hind (1820-1889) witnessed one such hunt in 1857 and described it in these words: “Until the herd is brought in by the skilled hunters, the utmost silence is preserved around the fence of the pound: men, women, and children, with pent-up feelings, hold their robes so as to close every orifice through which the terrified animals might endeavour to escape.”

The ancestral homelands of the Ojibwa (also called Ojibwe and Ojibway) cover much of the Great Lakes region in the Eastern Woodlands. Often known in the United States as the Chippewa, they are part of the larger group of the Anishinaabeg. The Ojibwa now living in southeast Manitoba and northwest Ontario are often called Saulteaux, after the rapids of present-day Sault Ste Marie, where they used to gather in the summer months.

In the 17th century, some Ojibwa moved southward, into Southern Ontario and present-day Wisconsin and Minnesota, in the United States, where they clashed with the Dakota.

Over the years, some Ojibwa bands spread westward and northward into the Prairies. Despite adopting traditions and customs of the Plains people, the Ojibwa retained many traits of their past life in the East. Plains Ojibwa women, for instance, used to decorate their folded rawhide containers (also known as parfleche bags) with floral designs similar to those used in the Eastern Woodlands. Over the years, some Ojibwa and Cree bands merged to form Oji-Cree communities, while some Cree also intermarried with the Assiniboine.

Among the Cree, the Sun Dance was called the “Thirsting Dance.” It took place during summer and unlike other groups, both the Cree and Ojibwa used to build a nest made of branches atop the sacred central pole. Painted or incised, it was known as the “Thunderbird nest.” Dances often lasted days. The dancers would continue to dance in place to the rhythm of chanted prayers, never stopping to eat, drink, or rest, or looking away from the top of the central pole.

Plains Cree reportedly tattooed their bodies and faces. Women usually tattooed straight lines across their chins, while men would also tattoo their chests. Although the Plains Cree tend to be concentrated in Alberta and Saskatchewan and the Plains Ojibwa tend to live on reserves in eastern Saskatchewan and Manitoba, many Cree continue to live on reserves alongside the Ojibwa and Assiniboine.

From Manitoba in the east to Saskatchewan and Alberta in the west, for decades before the Europeans made their first appearance on the North American continent, the Plains were home to various First Nations. From the Blackfoot to the Cree, from the Dakota to the Stoney and Assiniboine, the First Nations of the Canadian Plains have captured the popular imagination with their rich culture, their beautiful feather headdress, and their complex dances and ceremonies. For far too often, however, the people of the Plains have been equated with the stereotype of the Hollywoodian “Indian.” Today, their descendants continue to resist these Western stereotypes, while reclaiming the complexity of their culture and the nuances of their languages.