Frank Gehry’s architectural designs left a significant mark on the late 20th century, making his name widely recognizable. Through the use of bold, deconstructive forms, innovative materials, and a sculptural approach that challenged conventional design forms, Gehry redefined contemporary architecture. In this article, we will explore Gehry’s life and how his background, as well as his sources of inspiration, led him to develop his own unique style and legacy. Let’s explore the mind and methods of one of architecture’s greatest visionaries.

Frank Gehry’s Youth and Upbringing

Frank Gehry was born in Toronto, Canada, on February 28, 1929, as Ephraim Owen Goldberg. The name Ephraim, given to Gehry by his grandfather, was used by the architect only during his bar mitzvah. Frank, in turn, was the name he was commonly called, while Gehry, which is so synonymous with the architecture that we know today, was taken on by the architect later in his life.

As a child, Gehry would use wood shavings from his grandfather’s hardware store to build imaginary homes and cities. His grandmother, who would often assist in this creative activity, is regarded by Gehry as an early influence on his work. Gehry’s mother, Thelma, would often take her son to see concerts and introduce him to various arts. His father, Irving, on the other hand, was a former boxer who traveled around selling pinball and slot machines. From time to time, Gehry would accompany him on sales calls, which often included stops at bars.

Gehry himself mentioned that thanks to these very different activities, a balance was kept during his upbringing. One can imagine that Gehry, as a result of these different influences, developed a unique perspective. One that blended artistic sensitivity with a keen awareness of everyday life. The contrast between the refined world of art and music and the more gritty, fast-paced environment of bars and sales may have shaped his ability to merge the unconventional with the sophisticated in his later architectural work.

After growing up in Timmins, a small mining town in Eastern Ontario, Canada, the family moved to Los Angeles, California, in 1947. The main reasons for the move were the loss of business during the war years and the resulting financial struggles, as well as Gehry’s father’s health complications. When he suffered a heart attack, the doctor recommended a change of scenery.

After the war, Los Angeles not only offered a better climate in terms of weather, but also in terms of economic opportunities. From the moment Gehry and his family arrived, Los Angeles became his lifelong home. As a result, he came to be recognized as a true LA architect.

Studying at the University of Southern California and Harvard

Los Angeles became the place where many important parts of Gehry’s life and career took place. When Gehry and his family arrived in this warm and sunny city, the nineteen-year-old high school graduate took on a job as a truck driver to pay for his night-school art classes. Although Gehry likely felt drawn to a more artistic path, architecture was not his immediate focus. His interest in getting a degree in this field truly took shape after one of his teachers invited Gehry to visit a construction site. During the visit, Gehry was deeply moved by the way the architect articulated his vision and the concerns that shaped his decisions.

Once inspired and convinced that architecture was the path he wanted to pursue, Gehry enrolled in the School of Architecture of Southern California (USC). He studied there between 1949 and 1954, graduating with a degree in architecture. Subsequently, after having worked for the U.S. Army Special Services Division for a year, where he designed furniture for the enlisted soldiers, he continued to study City Planning at Harvard Graduate School of Design in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After a year, Gehry dropped out of this course and returned to California. What followed were several years of work at established architecture firms—including one in Paris—before he opened his own design company in Los Angeles in 1962, called Frank Gehry & Associates. Later, in 2001, he renamed the company Gehry Partners.

Gehry later recalled that he didn’t see himself as a businessman but that the business model he set for the office turned out to be a good one. Gehry adhered to a few fundamental principles—most notably, never borrowing money and ensuring his employees were always paid, which gave the company a solid reputation. He also said that the first few years were difficult financially, which in turn made it hard to hire the skilled people he needed. As a result, Gehry did most of the work himself and struggled to deliver perfectly finished structures. “Buildings leak when you don’t have enough construction experience,” Gehry once said.

While Gehry was studying and building his company, he was with his first wife, Anita Snyder. The two got married in 1952 and remained together for fourteen years before separating in 1966. Together, they had two daughters, Brina and Leslie. It was actually Snyder who encouraged Gehry to change his Jewish surname, Goldberg, to a different, more neutral name. Snyder considered this a smart move because it would give their children a more neutral starting point in a world where antisemitism was still ingrained in many parts of society. Gehry himself had been beaten up as a child for being Jewish, and Snyder feared the same would happen to their daughters. However, Gehry has said that if asked today, he would not have changed his name.

Influences and Inspiration

One of the most significant sources of inspiration for Gehry came from his childhood experiences. A notable example is the recurring fish motifs that Gehry used in many of his designs, which stem from a vivid childhood memory. On Friday nights, Gehry’s grandmother would let a live carp swim around the family bathtub before preparing gefilte fish for the Sabbath meal. This ritual left a lasting impression on Gehry, influencing his artistic sensibilities in ways he didn’t always anticipate. He once remarked that, despite consciously deciding to move away from the fish shapes, it would inevitably find its way back into his work, almost as if it were an instinctive, deeply ingrained element of his creative expression. Moreover, as Gehry also ventured into furniture design later in his career, his use of fish motifs extended beyond architecture.

Another source of inspiration for Gehry came from the modernist designs of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, who helped establish Scandinavian modernism. Their clean geometric lines, free of decoration or ornament, were in fact an inspiration to many in the 1960s, the period when Gehry’s career was just beginning to take off. Although Gehry experimented with similar concepts, he soon felt the need to explore further. He aimed to incorporate a sense of humanness in his designs—something he found lacking in the more formulaic modernist buildings.

Through museum visits with his mother, he learned about contemporary painters and sculptors, developing both an appreciation and an eye for the arts. Later in life, he was deeply influenced by the avant-garde West Coast art movement and formed friendships with artists like Ed Moses and Billy Al Bengston. His interactions with these artists exposed him to experimental art forms that challenged traditional boundaries and encouraged him to adopt a more unconventional and innovative approach to his own work. This also led Gehry to incorporate non-traditional materials and forms into his architecture.

Frank Gehry’s First Experiments

Gehry deviated from the functional, and more impersonal modernist style, to explore a sense of humanness. By the mid-1960s, a few years after opening his own design firm, he experimented by incorporating unconventional, playful features into his designs. One of the things that defined these specific features was their materials. Instead of giving his buildings a standard finish, Gehry chose to visibly use materials that would normally be hidden once a building was properly finished. Think of plywood, rough concrete, and corrugated metal. Additionally, the features in Gehry’s buildings could be called unconventional or playful because of their irregular, dynamic shapes, which felt more organic and engaging.

Furthermore, these features were designed to enhance the human scale of the buildings. Because of what appeared to be imperfect, people could feel more comfortable in and around the structures, and more at ease while approaching them. Finally, the way Gehry designed the different spaces of his buildings was meant to contribute to the same sense of ease, as they encouraged movement and interaction instead of imposing a strict layout. Overall, Gehry’s experimentation resulted in buildings with a more natural feel for human interaction, movement, and experience. A prime example of a design that expressed these aspects was Gehry’s own home in Santa Monica, California.

The Development of Frank Gehry’s Personal Style

As Gehry’s career progressed, his designs became increasingly sculptural and dynamic, departing more and more from the rectilinear forms of traditional architecture. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he embraced asymmetry, irregularity, and a sense of movement in his buildings. They almost appeared to be contemporary works of art. Because there was an aspect of fragmentation in Gehry’s designs and he was able to undermine the viewer’s expectation, he was grouped with the deconstructivist movement in architecture. The deconstructivists sought to fragment and distort conventional architectural forms to create dynamic, non-linear compositions.

Apart from their sculptural, dynamic character, Gehry’s designs also continued to be defined by the innovative use of unconventional, industrial materials. Inspired by his early experiments, he consistently incorporated titanium, stainless steel, and exposed wood into his architecture. Additionally, his experimental nature led him to explore digital design technologies, using computer software to create complex, curvilinear forms that would have been difficult to create with traditional drafting techniques.

In 2002, Gehry even founded an AEC (Architecture, Engineering, and Construction) software company called Gehry Technologies, as a spin-off from the innovative processes developed within Gehry Partners. As part of this venture, the company launched GTeam in 2011, an online Building Information Modelling (BIM) platform designed to improve collaboration and streamline communication among project stakeholders. GTeam enabled architects, engineers, and contractors to share and coordinate building data in real-time, facilitating a more integrated and efficient design and construction process.

The use of unconventional materials and sculptural designs was meant to create buildings that evoked emotions and that engaged with their surroundings. Instead of lifeless, stale structures, Gehry viewed buildings as living, breathing entities that should interact with the people and environments around them. Gehry’s play upon traditional architecture and his reaction against the austerity and formality of modernist designs also caused him to be associated with postmodernism. His buildings were functional yet artistic, making him a true innovator of his time.

Gaining Recognition and Building Fame

Gehry’s rise to fame was not immediate, as his unconventional approach initially faced scepticism—a process, one could say, is typical for anyone who breaks with tradition and the status quo. Gehry’s big break came in the 1970s and early 1980s, when he gained attention for his home in Santa Monica. In fact, a perfect representation of the various ways Gehry was perceived throughout his career was his neighbor’s reaction to his home. Initially, some neighbors disliked his experimental reconstruction so strongly that they took him to court. Yet, later on, those same neighbors remodeled their own home to mirror Gehry’s.

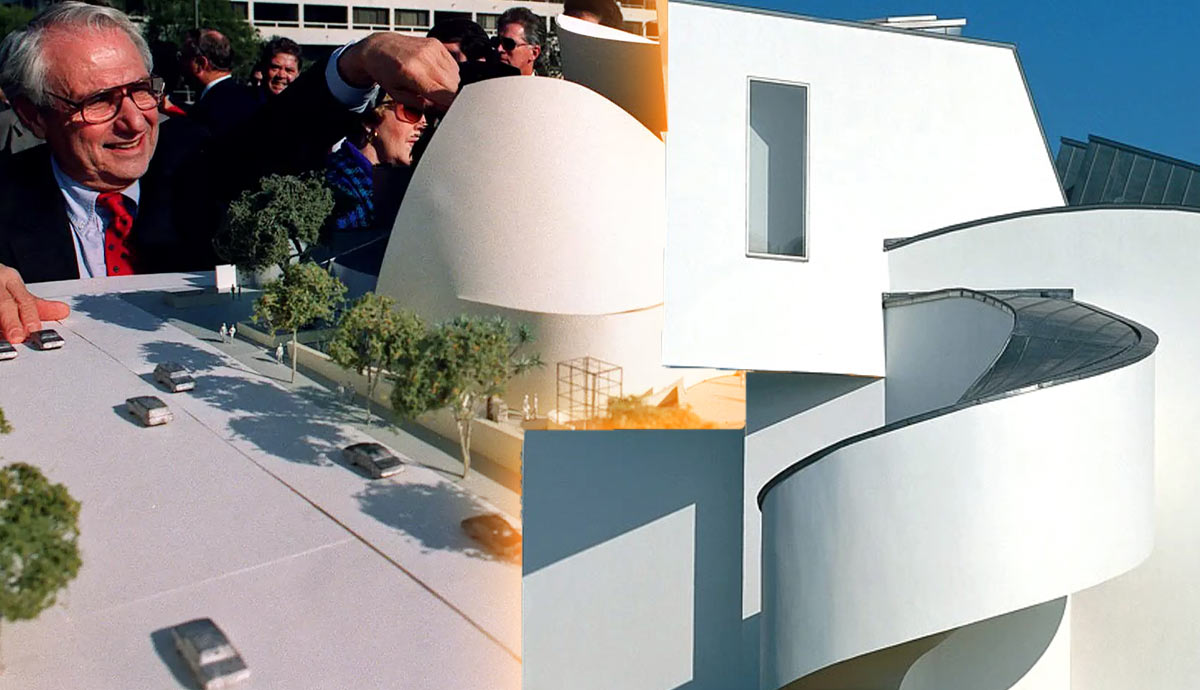

As the architect continued to challenge architectural norms, commissions from high-profile clients started rolling in. His reputation solidified in the late 1980s and 1990s with projects like the Vitra Design Museum in Germany and the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis. Yet, there was one project that truly propelled Gehry to stardom: the 1997 Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. This shimmering, titanium-clad masterpiece not only redefined museum architecture but also sparked what became known as the Bilbao Effect, proving that architecture could revitalize entire cities. From the completion of the Bilbao Museum onwards, Gehry’s name became synonymous with visionary, boundary-pushing design.

Frank Gehry’s Legacy

Today, Gehry is well known for various groundbreaking architectural works. Some of the most notable ones include the previously mentioned Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, the Dancing House in Prague, and the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. Even in his nineties, Gehry continues to produce new designs. Recent examples include the LUMA Arles Tower (2021) and a housing development at London’s Battersea Power Station (2022). All of these buildings embody Gehry’s signature fluidity and sculptural dynamism.

While his oeuvre might not even be complete yet, his legacy is already cemented as one of the most transformative forces in modern architecture. The fact that Gehry is known for innovative, artistic buildings is a testament to the fact that throughout his career, he maintained a strong belief in the importance of artistic experimentation and pushing boundaries. He inspired a new generation of architects to think outside the box and showed that buildings can be both functional and expressive. While Gehry himself remained deeply connected to Los Angeles, the city that was so formative for his life and career, his work is spread all over the world and recognized globally.

Gehry himself once said: “Architecture should speak of its time and place, but yearn for timelessness.” This is something that certainly applies to his own work, which continues to captivate, challenge, and inspire. Through Gehry, the world knows about the boundless possibilities of architectural design.