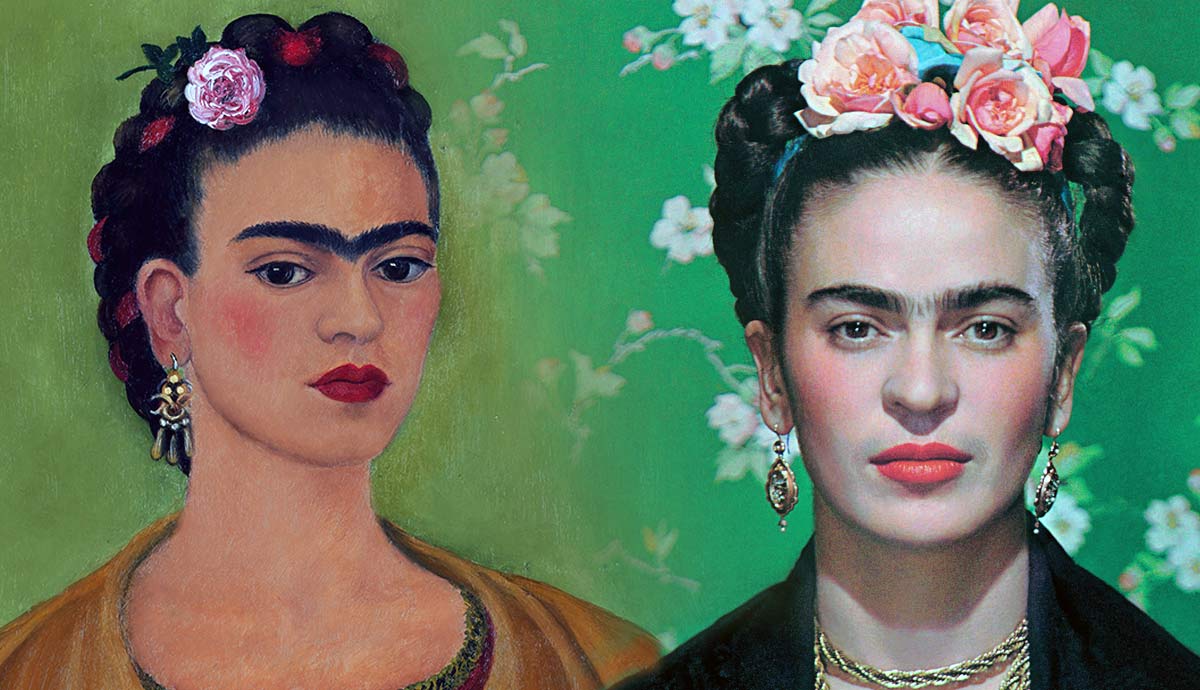

Characterized by deep symbolism and vibrant color palettes, the works of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo have been described as introspective and deeply personal. Best known for her powerful self-portraits, Kahlo’s works reflect lifelong health struggles, including her chronic pain and disability, as well as a troubled love life. Fuelling her unique artistic style, these experiences inspired her poignant exploration of identity, pain, and loss. This article looks at the fascinating life of Frida Kahlo and explores her legacy and influence through the vivid masterpieces she left behind for her world.

Frida Kahlo’s Formative Years

Born to a Hungarian-German father and a Mexican mother of Native American and Spanish descent, Frida Kahlo spent her childhood in Coyoacán, Mexico. Her family home, today a museum dedicated to her life and legacy, was called La Casa Azul, which translates to “The Blue House.” At the tender age of six, Kahlo contracted Polio. Bedridden for nearly nine months, Kahlo’s right leg and foot grew thinner than her left one due to the disease. Even after recovery, she was left with a slight limp and resorted to wearing long skirts ever since to avoid drawing attention to her disability.

Despite her chronic pain, Kahlo participated actively in sports and excelled academically. She was accepted to the prestigious Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (National Preparatory School) in 1922 at the age of 15. As one of the 35 women in the school, Kahlo was set for a promising future in medicine and was known for her outspoken nature. She was part of a political group in school called “Los Cachuchas,” where its members had a voracious appetite for knowledge, politics, and philosophical discussions. Vocal about countering conservatism, many of these individuals would later become influential figures in the realms of politics, law, arts, and literature in Mexico.

A Harrowing Accident That Changed Her Life Forever

In September 1925, Kahlo was traveling on a bus with Alejandro Gomez Arias, the leader of Los Cachuchas, who was also her boyfriend at the time. While overtaking, the bus collided with an electric trolley car moving at high speed. There were those whose lives were taken instantly and many others who succumbed to their injuries later in the hospital. Kahlo survived the harrowing accident but sustained severe injuries after a steel handrail impaled her pelvis. When a passerby tried to help her remove the rod, she reportedly “screamed so loud that no one heard the siren of the Red Cross ambulance.” Kahlo also suffered fractures to her spine, as well as injuries to her abdomen, collarbone, and shoulder.

Recalling the traumatic ordeal later, Kahlo poetically described how “the handrail pierced [her] as the sword pierces the bull.” Following the accident, she began an arduous recovery process, one that confined her to the bed in a plaster cast and radically transformed her worldview. As the accident took away her freedom, it also shattered Kahlo’s dreams of becoming a doctor. To aid her recovery, Kahlo’s parents encouraged her to paint with a lap easel. They also installed a mirror in her bed’s canopy for her to paint her own face. Kahlo expressed her pain and suffering vividly through her paintings and completed her first self-portrait in 1926 while on bed rest. By 1927, Kahlo was well able to resume her social life.

The “Other Accident”: Meeting and Marrying Diego Rivera

“I have suffered two serious accidents in my life, one in which a streetcar ran over me … the other accident is Diego.” – Frida Kahlo

The famous quote by Kahlo herself summarises her decades-long, tumultuous relationship with Diego Rivera, a fellow Mexican artist whom she married in 1929. This was the first marriage for Kahlo and the third for Diego. Characterized by intense passion alongside fights and infidelity, their union was subjected to much media scrutiny. Equally passionate about the country’s fate following the Mexican Revolution, the couple bonded over a shared belief in Marxism and “Mexicanidad,” as well as their love for the arts.

Kahlo’s affinity with Rivera began years back in 1922 when she observed him painting a mural in her school. The commonly accepted lore was that they only reconnected in 1928 at a party hosted by Italian-American photographer Tina Modotti. However, according to Rivera’s memoirs, he met Kahlo again when he was working on the murals in the Ministry of Education building, sometime in 1925. She wanted him to look over her paintings, insisting on “an absolutely straightforward opinion” on whether she would become “a good enough artist.” Diego was immediately impressed and saw Kahlo as “an authentic artist” whose works “revealed an unusual energy of expression, precise delineation of character, and true severity.”

Life in the United States: The Start of the End?

In the early 1930s, the couple traveled to the United States, where their relationship was tested on several occasions amid moments of grief. Rivera found success after receiving several high-profile mural commissions in the likes of the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Rockefeller Center in New York City. Kahlo, on the other hand, grew increasingly disillusioned with the superficial socializing with high-society guests, as well as the industrialized and overpopulated America. Through her painting titled Self-Portrait Along the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States (1932), she expresses her poignant longing for the agrarian culture and simpler life in Mexico unburdened by capitalism and modern industry.

In July 1932, Kahlo suffered a miscarriage, leading to a serious hemorrhage that required two weeks of hospitalization. In her surrealist self-portrait Henry Ford Hospital (1932), Kahlo expressed the crippling sense of helplessness she felt during the miscarriage. She depicted her naked, bleeding body lying on a hospital bed while being tied to six symbolic objects hovering around. They were a snail, a male fetus, a lavender cattleya, a piece of medical equipment believed to be an autoclave, a teaching model of female reproductive anatomy, and a human pelvis bone. Kahlo’s unspeakable pain of losing a child was compounded by the heartbreaking news of her mother’s death from surgical complications in Mexico months later.

Failing Marriage and Ailing Health

Unable to adjust to life in the United States, Kahlo longed to return home to Mexico, despite Rivera’s reluctance. By early 1934, the couple was back in Mexico City in the San Ángel neighborhood and frequently hosted artists and political activists at their residence. Between 1934 and 1939, Kahlo and Rivera were confronted with problems in their marriage, which had become strained because of infidelities on both parties. A serial womanizer, Rivera had affairs with multiple women, including Kahlo’s biological sister Cristina who was the subject of his paintings. While married to Rivera, Kahlo, too, had numerous lovers, including American photographer Nickolas Muray, American artist Isamu Noguchi, and former Soviet leader Leon Trotsky.

During this period, Kahlo also struggled with a series of health problems, which left her physically and emotionally drained. She had undergone an appendectomy, two abortions, the amputation of gangrenous toes, and numerous foot operations. In the symbolism-rich painting What the Water Gave Me (1938), an intimate perspective of Kahlo resting in the bathtub reveals her innermost struggles and memories. Death and destruction featured prominently: we see a skyscraper emerging from an erupting volcano, a skeleton resting at the fool, seashells with bullet holes, and a lifeless woodpecker on a tree. At the center of the painting is a naked female figure floating on the water. Nearby, there is a couple, believed to be Kahlo’s parents and two female lovers of different skin tones in bed (they later reappeared in her painting Two Nudes in a Forest).

Personal Struggles Amid Growing Recognition

In November 1939, following her divorce from Rivera, Kahlo moved back to La Casa Azul to focus on her career and earning her own living. There she embarked on a productive period, successfully completing several masterpieces, including The Two Fridas (1939) and Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940). In the latter, she depicted herself with cropped hair and masculine clothing, demonstrating her independence and celebrating life after divorce. Kahlo also enjoyed growing acclaim as an artist, with her works featured in three international exhibitions in Mexico City, New York, and San Francisco. In August 1940, amid her declining health exacerbated by alcoholism, Kahlo received the tragic news of Trotsky’s assassination which left her inconsolable.

While in San Francisco for her back pain treatment, Kahlo reconnected and reconciled with her ex-husband Rivera. The pair remarried in December 1940 and returned to Mexico City, agreeing to give each other more space in the marriage. Throughout the 1940s, Kahlo’s ill health continued to be a source of torment as she battled spinal problems, pain in her leg, chronic hand infection, and syphilis among others. As a result, she was largely confined to La Casa Azul, tending to the house and keeping numerous pets as company. Despite her back pain rendering it difficult to stand or sit for a long period of time, Kahlo continued working on her paintings. The Broken Column (1944) and The Wounded Deer (1946), two of Kahlo’s most prominent works, reflected her ailing health and struggle with chronic pain.

Kahlo’s Final Years and Death

As she neared the final years of her eventful life, Kahlo’s pain and health struggles escalated. In 1950, she was hospitalized for almost a year at American British Cowdray Hospital in Mexico, during which she underwent seven surgeries for her spinal condition. Post-discharge, Kahlo relied on a wheelchair and crutches to move about in La Casa Azul, where she spent most of her time. Later, Kahlo had to have her right leg amputated due to gangrene, leaving her severely depressed and increasingly reliant on painkillers.

In her final years, despite her poor health, Kahlo remained as active as she could in political activism, rejoining the Mexican Communist Party and helping to collect a list of signatures supporting the World Peace Council. Shortly before her death in July 1954, Kahlo even attended a demonstration protesting the CIA invasion of Guatemala, which ultimately worsened her bronchopneumonia. Her nurses would find her dead in bed, in less than two weeks after her last public appearance. Rivera saw to the funeral arrangements, ensuring that Kahlo was given a dignified state funeral. Hundreds of mourners, alongside prominent Mexican cultural and political personalities, showed up to pay their last respects to Kahlo. She was laid to rest in traditional Tehuana clothing, and her coffin was draped in a flag that bore the quintessential communist symbols of a hammer and a sickle.

Frida Kahlo’s Legacy: Mexico’s Most Enduring 20th-century Artist

While Kahlo is known as one of Mexico’s most prominent modern artists, she did not enjoy the same level of fame in her lifetime. After her death, her reputation grew significantly when feminist scholars reclaimed her work as part of the rising feminist movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Interest in her life and work was soon renewed as she was celebrated as a feminist icon. By 1984, the Mexican government declared her works a national cultural heritage, with record-breaking sales figures in international auctions.

Today, beyond feminism, Kahlo’s experiences have resonated with multiple communities as she is hailed as a queer and disabled icon. Her catalog of masterpieces hangs proudly in museums all over the world. Reproductions of her famous self-portraits can be found plastered on souvenirs and murals all over the world, likening her to equally recognizable figures such as Che Guevara and Bob Marley. Her vibrant fashion style, deeply rooted in Mexican tradition, has also left a profound impact on stylists and designers, including Dolce & Gabbana and Jean Paul Gaultier. As an enduring beacon of resilience and strength, Kahlo continues to influence contemporary artists and audiences, captivating the world with her dramatic and extraordinary life story told through vivid and rich canvases.