Numerous revolutions and uprisings in the name of nationalist causes marked the 19th century. The forces of nationalism and revolution shaped George Fisher’s world. In the early 19th century, he participated in multiple rebellions on two continents. However, Fisher was not exactly a professional revolutionary. Rather, he was caught up in significant social and political changes in Serbia, the United States, and Mexico. Fisher’s far-flung travels and role in the turmoil in Mexico and Texas in the 1830s attracted international notoriety. Some publications referred to Fisher as an “Adventurous Serb.”

George Fisher’s World

George Fisher was not even his actual name. He was born Đorđe Šagić in April 1795 to Serbian parents in present-day Hungary. His nickname, Đorđe Ribar, is believed by some to be the origin of his anglicized name George Fisher. In Mexico, he would be known as Jorge Fisher.

At the time of Fisher’s birth, most Serbs lived under Ottoman rule. However, Fisher’s parents were part of the Serbian Orthodox Christian minority in the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary.

Young Đorđe was sent to the Serbian Orthodox Church seminary at Sremski Karlovci. According to journalist and historian Misha Glenny, Sremski Karlovci was the center of Serbian cultural life in the Habsburg Empire (1999, 50). However, he was not destined to become a priest, as a Serbian revolt against the Ottoman Empire put this region of the Habsburg Empire on high alert.

Instead of continuing his training for the priesthood, Đorđe Šagić traveled across the Habsburg/Ottoman border to join the Serbian rebellion.

The Serbian Uprising

Đorđe Šagić volunteered to join the Serbian rebels in 1813. He joined a unit called the Slavonian Legion.

However, Serbs had been fighting the Ottomans since 1804. Misha Glenny explains that the rebellious Serbs in 1804 fought to remove corrupt local Ottoman officials, rather than for national independence. However, by 1813, the conflict evolved into a movement to drive out Serbia’s Ottoman rulers (1999, 8-9).

Unfortunately for Šagić and the Serbian rebels, the Ottomans launched a massive offensive in 1813 to crush the rebellion. As a result, historian André Gerolymatos noted that Serbian leader Karageorge (George Petrovic) fled to Habsburg territory (2002, 154). Šagić did not follow the Serbian rebel leadership into exile in his Habsburg homeland. Instead, he made his way across Europe, eventually arriving in Amsterdam.

A second Serbian revolt broke out in 1815. However, at this point, Đorđe Šagić left to begin a new life in North America by boarding a ship in Amsterdam bound for Philadelphia.

Arrival in North America: The Road to Texas

Đorđe Šagić or Ribar became George Fisher upon his arrival in Philadelphia in 1815. His emigration to the United States appears to be a turbulent story. Šagić and several others were detained upon arrival as redemptionists. This meant that since they could not afford to pay for their passage, Šagić and the others would have to work until they could pay the ship’s captain.

However, Šagić managed to lead the group’s escape from the captain. According to Claudia Hazelwood, people believed the escapees were fishermen, and thus Đorđe Šagić became George Fisher (1952).

Fisher’s movements are hazy for the next few years. However, we know that he made his way from Philadelphia to Mississippi by 1819. He became a US citizen there at some point in the early 1820s. Fisher also married Elizabeth Davis. The couple had three sons before divorcing in 1839. Fisher remarried on three other occasions.

In 1825, Fisher traveled to Mexico City with a business partner from New Orleans. This initiated a long-standing relationship with Mexico and the northern province of Texas, in particular.

Loyalty, Dissent & the Road to the Texas Revolution

Like many in the American South, Fisher saw the potential for Texas to be a profitable destination for land-hungry American settlers in their westward expansion.

According to historian Claudia Hazlewood, Fisher unsuccessfully sought to become an empresario (land agent) like Stephen F. Austin in 1827 (1952). As a result, Fisher decided to become a Mexican citizen in 1829 and secured a contract to settle five hundred families on land in Texas.

By 1830, Fisher was living in Galveston, where he served as the port’s administrator.

Mexico in the 1830s was embroiled in domestic political turmoil as military leaders and politicians vied for power. Fisher lost his position because he was labeled a supporter of an opposition leader in Mexico.

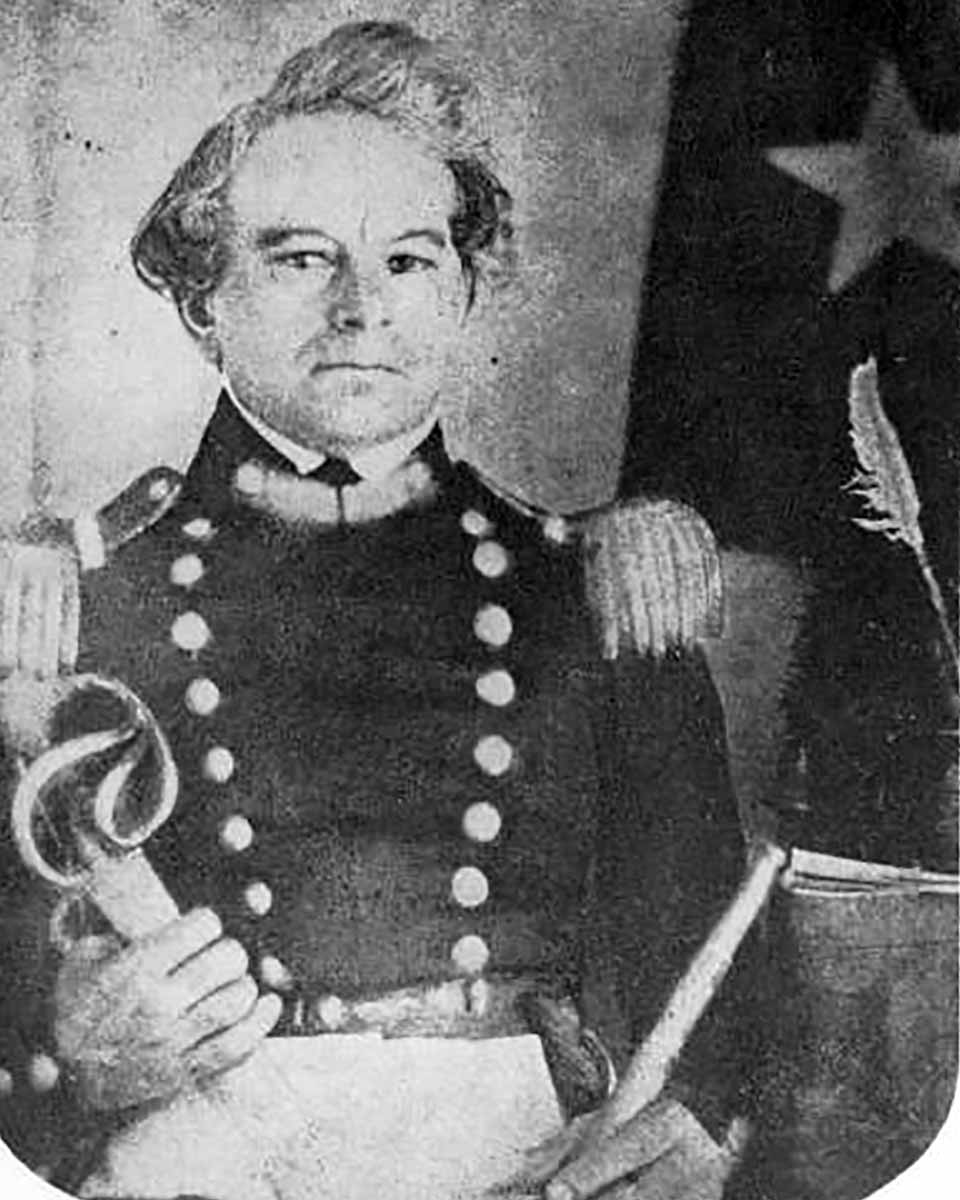

However, by late 1831, General Manuel de Mier y Terán appointed Fisher as customs collector at Anahuac on Galveston Bay.

While in Anahuac, Fisher played a role in one of the series of events that sparked the Texas Revolution. American settlers (Texians) and local Tejanos (Mexican Texans) alike opposed Mexican taxation policies enforced by Fisher at Anahuac. Angry American settlers threatened violence against Mexican officials and troops stationed in Anahuac.

Fisher fled Texan anger to Matamoros, Mexico, where he began publishing a newspaper, Mercurio del Puerto de Matamoros. He soon became involved in a failed insurrection against the dictatorship of Antonio López de Santa Anna.

In the future, the former Mexican bureaucrat Fisher and Texan rebels would have a mutual enemy in Santa Anna.

The Origins of the Texas Revolution

Fisher’s newspaper angered Mexican officials in Mexico City. However, Santa Anna’s regime soon faced a major challenge in Texas.

Increasing numbers of American settlers, especially from the slaveholding southern states, put pressure on Mexican officials in Texas. Historian H.W. Brands explains that slavery was officially abolished in Mexico in 1829 (2004, 149). Mexican officials in places like Anahuac wrestled with the question of whether to enforce the ban on slavery or permit Americans to settle with slaves in Texas.

Mexican officials, such as George Fisher and Juan Bradburn (born John Bradburn in Virginia), clashed with American settlers in Anahuac over more than just unpopular taxation policies. Like debates that would rage in the United States until the Civil War in the 1860s, Mexican officials and slaveholding, newly arrived American settlers fought over whether slavery should be permitted in Texas.

The explosive question of slavery and the number of increasingly assertive American settlers plunged Texas into crisis, made worse by the political turmoil in domestic Mexican politics.

American lawyer and Anahuac resident William Barret Travis became a leading agitator on the part of these anti-government pro-slavery settlers.

H.W. Brands notes that Bradburn arrested Travis for his agitation and threatened to execute him after an armed mob gathered to attack the prison. Although the incidents at Anahuac in 1831-1832 did not result in a significant escalation, they emboldened the pro-slavery American settlers to continue to resist Mexican policies (2004, 166-167).

Fighting between Texan rebels and Mexican forces broke out in April 1835.

Texas: From Independent Republic to US State

Texans meeting to discuss the province’s future in 1835 did not initially want to declare independence from Mexico. Even several battles between Texan rebels and Mexican troops did not immediately result in popular calls for independence. For example, historian James E. Crisp notes that delegates meeting in San Felipe de Austin in November 1835 declared their loyalty to the Mexican Federalist Constitution of 1824 (2005, xiii).

However, the volatile political situation in Mexico, where supporters of Federalism clashed with those in favor of centralization, only further destabilized Texas.

Mexico’s dictator, General Antonio López de Santa Anna, threatened a crackdown on troublesome American settlers in Texas.

Santa Anna, dubbed the “Napoleon of the West,” personally led a Mexican army to crush the rebellious Texans. Santa Anna’s troops besieged Texan forces at an abandoned Spanish mission known as the Alamo in San Antonio de Béxar. The Alamo’s co-commander was none other than William B. Travis from the Anahuac disturbances.

Texans formally declared their independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836. On March 6, Santa Anna’s forces seized the Alamo and annihilated the defenders.

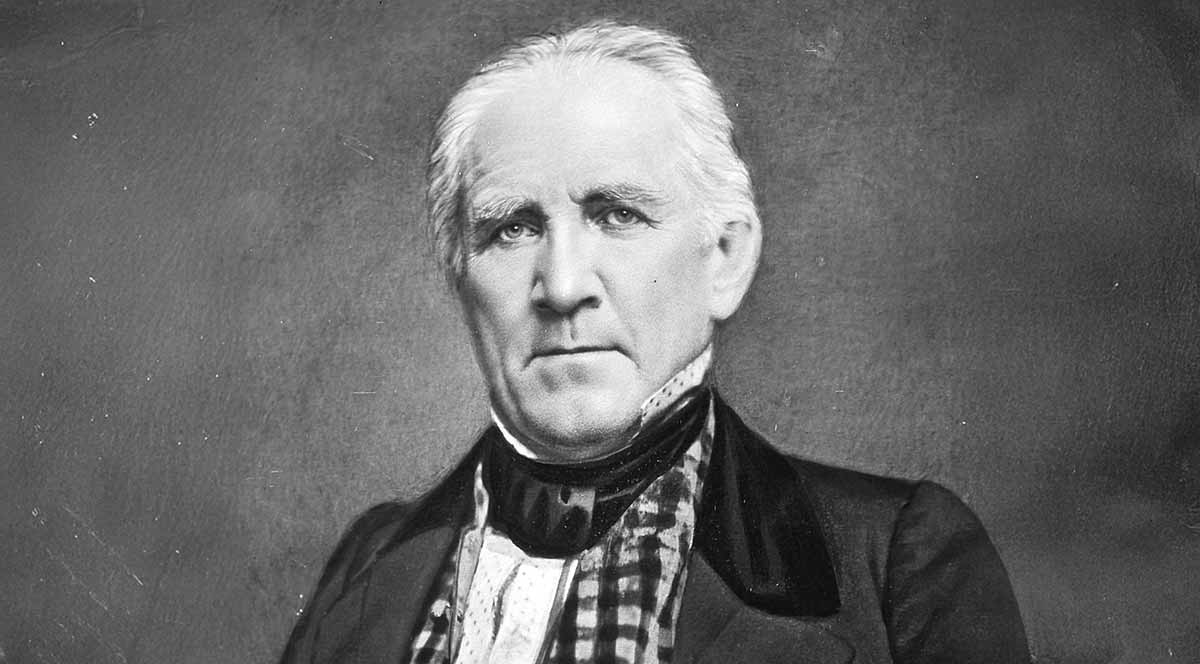

General Sam Houston, the commander-in-chief of the Texan rebels, decisively defeated the Mexican army and captured Santa Anna following the Battle of San Jacinto in April 1836. Historian James L. Haley notes that the battle secured Texas’s independence and paved the way for Houston to become President of the Republic of Texas (2002).

In December 1845, Texas became a state of the United States.

George Fisher’s Later Life and Legacy

George Fisher returned to public service in the independent Republic of Texas. He served as a justice of the peace, a land agent, an officer in the Texas militia, and a member of the Houston City Council.

The “Adventurous Serb” George Fisher continued to be a public servant wherever he lived. He left Texas in the late 1840s and eventually settled in San Francisco, California.

Fisher ended his public service career as the consul for the Kingdom of Greece in San Francisco in the 1860s. Fisher died in San Francisco on June 11, 1873.

George Fisher’s life was shaped by the powerful forces of nationalism and the American expansionist doctrine known as “Manifest Destiny.” Nationalism drove the Slavonian Legion, to which Fisher volunteered to join during the First Serbian Uprising in 1813. Patriotic devotion to the “nation” inspired many similar uprisings in 19th-century Europe.

In the New World, Fisher participated in the nation-building projects of Mexico, Texas, and the United States. Fisher’s biography is a fascinating example of how these very different events in the 19th century were connected to a larger idea, such as nationalism.

References and Further Reading

Brands, H.W. (2004). Lone Star Nation: The Epic Story of the Battle for Texas Independence. Anchor Books.

Crisp, J.E. (2005). Sleuthing the Alamo: Davy Crockett’s Last Stand and Other Mysteries of the Texas Revolution. Oxford University Press.

Gerolymatos, A. (2002). The Balkan Wars: Conquest, Revolution, and Retribution from the Ottoman Era to the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Basic Books.

Glenny, M. (1999). The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804-1999. Penguin.

Haley, J.L. (2002). Sam Houston. University of Oklahoma Press.

Hazelwood, C. (1952). “Fisher, George (1795-1873).”https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/fisher-george. Texas State Historical Association.