Ancient myths and legends have fascinated artists and writers long after the civilizations that produced them collapsed. For centuries, mythological painting was a traditional subject matter, but in the 19th and 20th centuries, painters revived it by using modern techniques and formats. Read on to familiarize yourself with seven mythological creatures and stories that were reinvented by famous modern artists.

1. Pablo Picasso and Minotaur

Minotaur, the human-bull hybrid described in myths as a wild man-eating creature, was a product of the unfortunate obsession of King Minos’s wife with a white bull sent by gods. Minos, horrified by the bull-headed child, ordered to lock the creature inside a stone labyrinth and sacrifice men and women to it. Minotaur as a symbol became popular among the artists of the Surrealist movement. It embodied the Surrealist love for absurdity, interest in violence, and an undertone of perverse sexuality. Even the popular Surrealist periodical published by Andre Breton was called Minotaure.

Pablo Picasso associated himself with the Minotaur, referring to the conflict between human rationality and animal impulse. His works from the 1930s often featured the famous hybrid. One such painting was even the famous Guernica, which reflected the horror of the 1937 bombing of Guernica.

2. Gorgon Medusa by Franz von Stuck and Camille Claudel

The infamous Gorgon Medusa, whose gaze turned any living being into stone, was one of the most famous mythological characters in modern art. According to the most popular version of the myth recorded by the Roman poet Ovid, Medusa was a rape survivor, assaulted by the god Poseidon in a temple of another goddess, Athena. Instead of punishing the divine perpetrator, Athena directed her anger to his human victim. She turned Medusa into a snake-haired monster who could kill with her gaze.

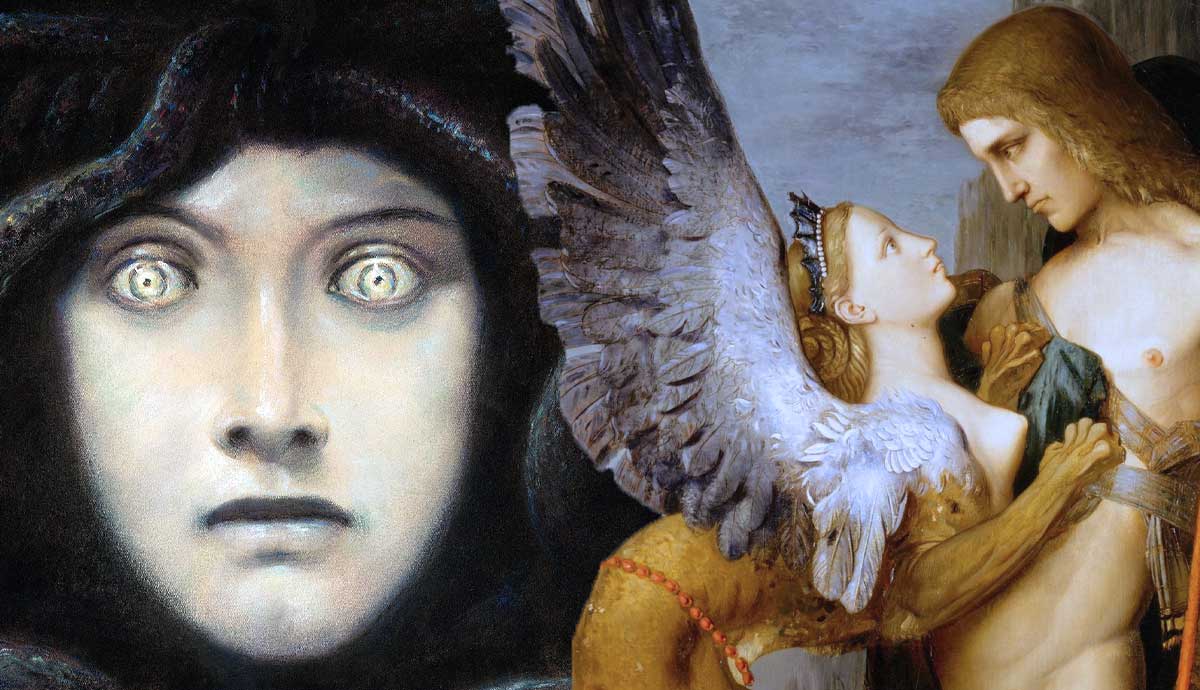

For centuries, Medusa’s image in art has been used as a thrilling and terrifying image of the feminine monster. In Symbolist art of the late 19th century, the Gorgon became the symbol of threat coming from an emancipated woman. The series of works by German painter Franz von Stuck represented Medusa as a pale supernatural figure, with her petrifying gaze turned to the viewer.

Feminist art historians interpret the myth of Medusa as the story of the threatening power of a victim’s gaze and the male fear of female retribution. They also mention that Medusa’s story is a tale of the further punishment of an already victimized woman. This context resonated with the heartbreaking work of Camille Claudel, who inserted a self-portrait into the figure of the decapitated Medusa. Perseus, the male hero famous for killing the monster, allegedly had facial features similar to Auguste Rodin’s.

Rodin was Claudel’s ex-partner, who used his fame as an established male artist to appropriate part of Claudel’s work and manipulate her feelings. After their breakup, Claudel was left alone, with no friends, art commissions, or even family around. Devastated, she suffered a mental breakdown and destroyed nearly all her work. Perseus and the Gorgon is one of the few surviving sculptures that reflects her pain and anger.

3. Polyphemus by Odilon Redon and Maurice Denis

Symbolist artist Odilon Redon had a profound interest in mythology and strange creatures that came from mystical dreams. These creatures, despite their odd and sometimes unsettling features, were rarely truly terrifying or dangerous. One of his most famous works presented a twist on the famous myths of the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, who fell in love with a water nymph called Galatea. In the original story, Polyphemus murdered Galatea’s human lover, whom she transforms into a water spirit. In Redon’s version, the Cyclops did not look capable of murder; rather, it was a gentle giant, sincerely and desperately in love, admiring his beloved from afar.

Another famous Symbolist, Maurice Denis, also painted Polyphemus in a manner that widely differed from the original thriller about a violent, unrequited love. His Polyphemus sat on a beach surrounded by families (the woman and children playing in the foreground are Denis’ family members), playing his flute for Galatea. The water nymph observed the cyclops from afar, and it seems that Denis’ version of the story might have had a kinder ending.

4. Cy Twombly and Bacchus

All artworks we have seen earlier relied on the narrative figurative style. But what if abstract painting could be used to tell stories of gods and heroes? The famous abstract painter Cy Twombly created a series of works that embodied the essence of the Roman god Bacchus. Most frequently, Greek and Roman deities were neither definitely good nor consistently evil. Rather, they embodied the positive and negative aspects and could both harm and aid humans. Bacchus was the god of wine, fertility, theater, and ritual madness. Associated with wine and celebrations, Bacchus also embodied depravity and violence, often caused by alcohol abuse. Cy Twombly’s monumental works with bright-red messy swirls of paint reflected both the loud celebration and drunken fever of Bacchus

5. Leda and the Swan by Paul Cezanne

The story of Leda and the swan was arguably one of the grossest episodes of Greek mythology and one of many stories that evolved around Zeus’ questionable sexual behavior. In this case, the thunder god appeared to the Spartan queen Leda in the form of a white swan, and either seduced or raped her, depending on the version of the story. Cezanne certainly preferred the former version of the tale, depicting Leda with flushed cheeks, with her arm embraced by the bird. In one of the original sketches for the work, Leda also had a champagne flute in her other hand. Before Paul Cezanne, the story appeared in Roman mosaics and was employed by the Renaissance artist as a curious and erotic subject from well-known mythology.

6. Orpheus by Jean Delville and Jean Cocteau

Orpheus was the mythical Greek poet and prophet. He accompanied the Argonauts in their quest for the Golden Fleece but was most famous for the unsuccessful attempt to rescue his beloved nymph Eurydice from the underworld. In Symbolist art, Orpheus became an immensely popular symbol of the gift and the downfall of an artist. In the mentality of the late 19th century, Orpheus’ prophetic gift and artistic talent marked him as a human who reached a new state of spiritual consciousness. Another powerful spiritual attribute was the vow of chastity he took after losing Eurydice. This decision became his downfall: he was torn into pieces by a group of female worshipers of Dionysus, either for refusing to pay them any attention or for denouncing his previous worship of the wine god. The ethereal work of Symbolist painter Jean Delville captured the poet’s demise, with his head on his trusted lyre sinking to the bottom of the river Hebrus.

The famous Surrealist poet and designer Jean Cocteau was so inspired by the figure of Orpheus that he created a series of films known as The Orphic Trilogy. The first film, titled The Blood of a Poet, featured performances by the famous war photographer Lee Miller and aerialist drag performer Barbette. Only loosely related to the Orpheus myth, it focused on an artist who traveled to a surreal world inside a mirror. The second film, Orpheus, was a contemporary retelling of the myth of Eurydice. Similarly to the Symbolists, Cocteau associated himself with the mythical poet and frequently returned to this figure in his writings and art.

7. The Sphinx and Gustave Moreau

In Egyptian and Greek mythology, the sphinx was a mythical hybrid with a human head and torso, the body of a lion, and occasional bird wings behind its back. While in Egyptian tradition, the being is either male or androgynous, in Greek and subsequent Western tradition, the sphinx turns into a woman. In Greek myths, the sphinx guarded the city gates and provided passage in exchange for a correct answer to its riddle. The unfortunate travelers who could not solve the riddle were devoured by the being.

In Symbolist tradition, sphinxes became even more feminized. Their feminine looks and violent animal nature made them the perfect embodiment of the femme fatale archetype—the cunning and overly sexual woman who lures men into traps. This popular archetype was a conservative reaction to the development of more rights and possibilities for women and the sexual liberation that was already underway. Sphinxes painted by Gustave Moreau embodied the fear of destructive and uncontrolled sexuality and the threats linked to it.