Henry Moore is widely regarded as one of Britain’s finest artists. His career spanned more than six decades, and his work continues to be considered highly collectible the world over. Although he is known predominantly for his large, curvaceous sculptures of reclining nudes, he was an artist who also worked with a variety of media, styles and subject matter.

From drawings of crowded tube stations during the London Blitz to completely abstract decorative textiles – Moore was an artist who could do it all. What’s more, his legacy as an all-rounder continues to this day through the work of the foundation set up in his name which helps artists and young people of all backgrounds to excel in their chosen field.

Henry Moore’s Early Life

Before his career as an artist, Henry Moore had set out to train as a teacher. When war broke out in 1914, his short-lived stint in that profession was cut short and he soon was enlisted to fight. He served in France as part of the Civil Service Rifles and would later reflect that he rather enjoyed his time of service.

However, in 1917, he was subject to a gas attack which hospitalized him for a number of months. When he recovered, he went back to the front line where he served through to the end of the war and beyond until 1919.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterIt was upon his return that his path towards becoming an artist first began in earnest. Given his status as a returning wart veteran, he was eligible to spend a period studying at art school, funded by the government. He took up the offer and attended Leeds School of Art for two years.

Henry Moore was heavily influenced by Cezanne, Gauguin, Kandinsky and Matisse – which he would often go to see at both Leeds Art Gallery and the many museums dotted around London. He was also influenced by African sculptures and masks, much like Amadeo Modigliani who had made a name for himself a few years previously in Paris.

It was at Leeds Art University that he met Barbara Hepworth, who would go on to become an equally, if not more widely renowned sculptor. The two shared an enduring friendship, which saw them not only move to London to study at the Royal College of Art; but continuing to make work in response to the other.

Sculpture

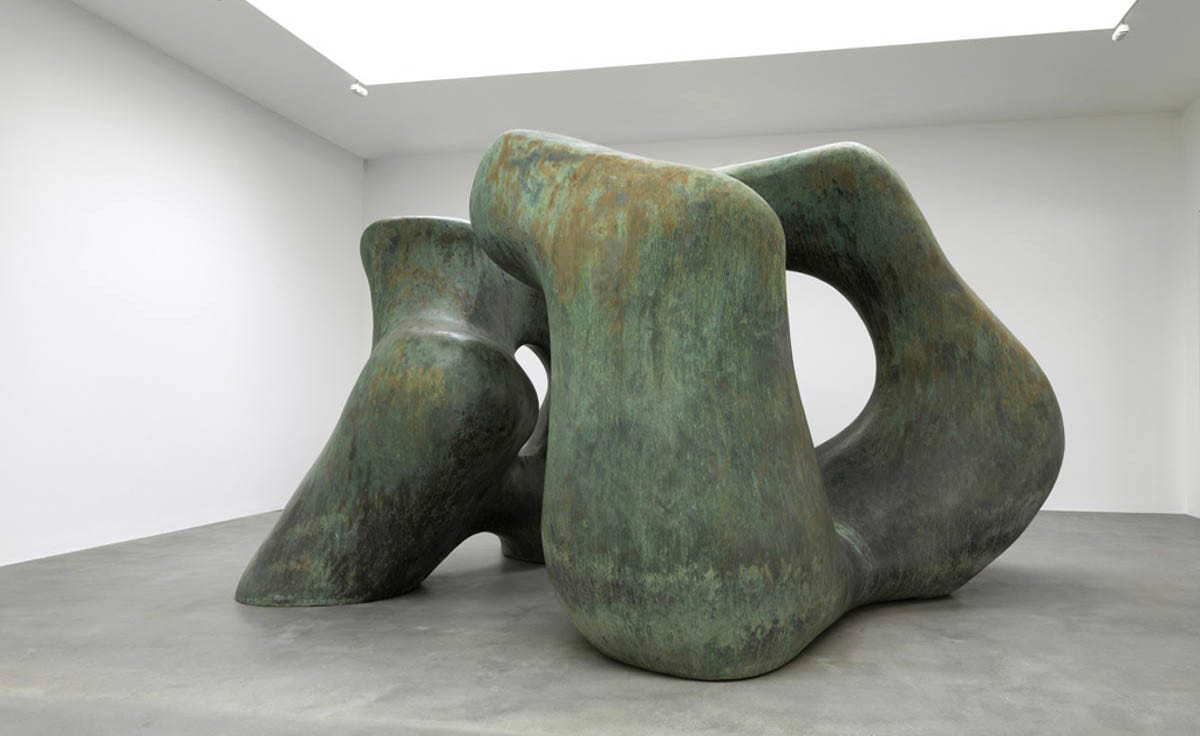

Henry Moore’s sculptures, for which he is most famous, bear a resemblance to and influence from his contemporaries such as Hepworth. However, his influences also include work by the likes of earlier artists, and in particular, Modigliani. The subtle abstraction, inspired by African and other non-western art, combined with the bold, non-linear edges make them instantly recognizable as each their own.

As Moore’s obituary in the New York Times put it, he saw it as his lifelong challenge “to get the two great sculptural achievements – the European and the non-European – to coexist,” in a singular form.

Throughout his career, Moore would use a variety of mediums to realize his sculptural vision. His bronze works are arguably some of his most recognizable, and the medium lends itself to the flowing nature of his style. Bronze, despite its physical composition, can give the feeling of softness and liquidity when in the hands of the right artist.

Similarly, when skilled artists like Henry Moore work with marble and wood (as he often did) they are able to overcome the material’s solidity and give it a pillowy, flesh-like appearance. This was ultimately one of the characteristics of Moore’s sculptures which made, and continue to make them, so compelling. It was his ability to present large-scale, inanimate objects with a sense of organic movement and tenderness, which few had ever been able to achieve before.

Drawings

Henry Moore’s drawn works are just as significant in the history of art and are equally, if not more, compelling in many cases than his sculptures. Most famously, he depicted his experience of the Second World War – which he saw this time from the home front.

He made a number of drawings of the scenes in the London underground, where members of the public sought shelter during the Blitz, during which the German air force rained bombs on the city of London for nine months between September 1940 and May 1941.

After all, Moore will have felt the impact of the bombings as strongly as anyone. His studio was badly damaged by a bomb strike and with the art market in shatters, he struggled to find the materials to make his usual sculptures – let alone find an audience who would buy them.

His drawings of the underground shelters convey the tenderness, vulnerability and even the humanity of the figures as they protect themselves from the onslaught above ground. Yet they also capture something of the unity and defiance which encapsulated the feeling of many Brits towards that period of time, and in Moore’s case, they were possibly even an act of defiance in and of themselves. The bombing might have limited his ability to make the work that he had become known for, but it couldn’t stop him from capturing the human body and exploring its condition.

Moore’s drawing skills are as powerful as his sculpting ability, and no doubt the one could not exist without the other. His studies of hands and bodies are reminiscent of the work of Käthe Kollwitz, yet he always left the parting inference of his own, ghostly and slightly abstracted style,

Textiles

As suggested previously, Henry Moore was not one to shy away from experimentation, both with regards to style but also medium. That’s why it may come as little surprise that he also tried his hand at textile design.

His abstracted forms, which manifested most notably in his sculptural work, naturally lent themselves to the process of geometric pattern design – which was increasingly popular in the post-war era.

Henry Moore dedicated himself to textile design between 1943 and 1953. His interest in the use of fabric began when he was commissioned, alongside Jean Cocteau and Henri Matisse, to create a design for a scarf by a Czech textile manufacturer.

For Moore, it was in the use of textiles that he could experiment most fervently with color. His sculptural works never allowed for this, and the content of his drawings was often either simply for the purpose of study or as a means of depicting the harshness of the British war-time experience.

For Moore, textile design was also a politically motivated means of making his work accessible to a wider audience. He was notoriously left-leaning in his political outlook, and it was his desire that art could and should be made accessible to all as part of every-day life; not exclusively for those who could afford to buy original artworks.

Afterlife

Henry Moore died at his home at the age of 88 in 1986. He had been suffering from arthritis for some time, no doubt the result of decades of working with his hands, as well as diabetes – though no cause other than old age was officially given for his demise.

Though he had seen enormous success in his life, there is no doubt that his legend has exceeded even his earthly fame. At the time of his death, he was the highest valued living artist at auction, with one sculpture selling for $1.2 million in 1982. However, by 1990 (four years after he died) his work had peaked at just over $4 million. By 2012, he had become the second most expensive 20th-century British artist when his Reclining Figure: Festival sold for around $19 million.

What’s more, his influence on the work of others continues to be felt to this day. Three of his own assistants would go on to become widely renowned sculptors in their own right later in their careers, and numerous other artists of all styles, media and geographies have cited Moore as a preeminent influence.

The Henry Moore Foundation

Despite the amount of money Henry Moore made as an artist, he always clung to the socialist outlook which had dominated his view of the world around him. During his life, he had sold works at a fraction of their market value to public bodies like London City Council in order for them to be displayed publicly in the less fortunate areas of the city. This altruism continued to be felt after his death, thanks to the foundation of a charity in his name – which he had been setting money aside for throughout his working life.

The Henry Moore Foundation continues to provide education and support to many artists and causes thanks to the money he set aside from the sale of his work during his life.

The Foundation now also runs the estates of his former home, which encompass a vast 70-acre site in the village of Perry Green in the Hertfordshire countryside. The site serves as a museum, gallery, sculpture park and studio complex.

The Henry Moore Institute, which is a subsidiary of the Foundation, is based within Leeds Art Gallery – forming an adjacent wing to the main building. The Institute hosts international sculpture exhibitions and looks after the main gallery’s sculpture collections. It also houses an archiver and library dedicated to Moore’s life and the wider history of sculpture.