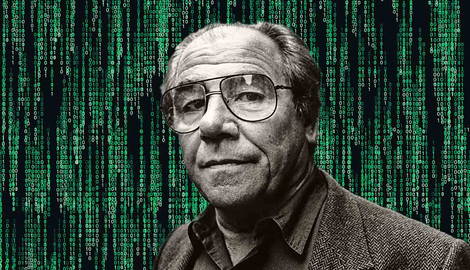

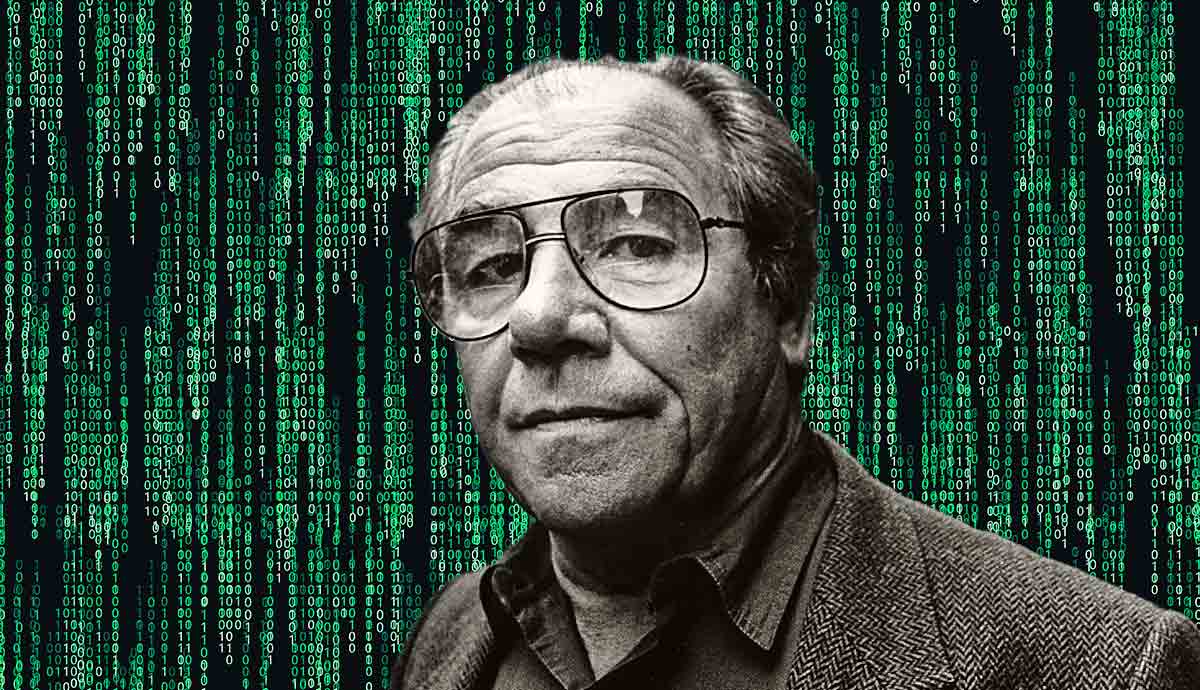

Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) was not the first philosopher to be huddled under the trendy umbrella term of “postmodernism,” but he is, with other sages like the American Fredric Jameson, among the most prominent. His voluminous writings on everything from consumerism to the US-led Gulf War may have ranged from the caustically brilliant to the impishly obscure, but there is no question his legacy shines on, arguably even brighter in the infinitely digitized hall-of-mirrors Internet age. Without further ado, let’s review the highlights.

Jean Baudrillard: Changing Channels

Born in Rheims, Jean escaped his family’s rustic life, leaving to attend Paris’ prestigious Sorbonne in the early 1950s to study German. He then taught it at the secondary level for much of the decade before returning to the Sorbonne for his doctorate, switching métiers as a protégé of the noted postwar sociologist Henri Lefebvre. In the mid-1960s, Baudrillard in turn would become a professor of sociology at the Sorbonne’s Nanterre University, then a hotbed of neo-Marxist political and cultural thought.

Like many leftist French (and European) intellectuals of that era, the near-revolutionary “events” of May 1968 would dim their worldview. Just as De Gaulle’s national government was teetering, crippled by escalating student-led protests and worker strikes, the French Communist Party retreated, and the movement (and moment) collapsed. Many on the liberal and socialist left were left disillusioned, if not roundly defeated. How could the Marxist prediction of the inevitable—and righteous—victory of the working-class proletariat over the bourgeois power structure be so wrong?

While the prevailing answer would blame an entrenched, self-justifying capitalist ideology allied with the pacifying fruits of middle-class prosperity, Baudrillard thought that the Marxist model itself was fatally flawed. By its simplistic, materialist concentration on the proletariat as an agent of production, thus mirroring the ruling class, Marxist thought was reductive, leaving no space for the symbolic desires and rewards inherent in society.

Missing the Marx

Just as Karl Marx (with his collaborator Friedrich Engels) failed to predict the victory of the 1930s Western welfare state, buffering the Depression, he also didn’t foresee that owners and workers alike would be seduced by the allure of what the prescient U.S. economist Thorstein Veblen famously called “conspicuous consumption.” Marx confined his thoughts on mass-produced or man-made capitalist goods to their basic “use value” (or “exchange” value). Baudrillard and others (for instance, the German “Frankfurt School” of the 1920s) expanded the concept, arguing that the “symbolic value” of goods is at least as important to a growing consumer class.

To take one contemporary example, consider the American SUV (sport utility vehicle). To a large extent, these super-sized, uneconomical (some say conspicuously vulgar) hybrid passenger automobiles ran circles over and around the U.S. car market starting in the 1980s and 1990s. While some owners surely benefit from the extra storage and tank-like safety features, in fact, their symbolic value outweighs their use value. Were it not so, a majority of Americans would be driving (and affording) cheaper, smaller, gas-saving compacts. These big, brawny, macho autos—monster passenger trucks too—are every bit about status, as they not only lend alpha-heft and gravitas to the passengers secured within, but allow them to sit literally “above” the puny vehicles in traffic beside them.

In a sense, then, one can argue that the average consumer, even a member of Marx’s lowly proletariat, has essentially been “bought off” by the materialist juggernaut that is modern global corporate capitalism. This is true despite the fact that the modern bourgeoisie are wealthier and more powerful than ever in the 21st-century gilded age, albeit usually covertly. Marx’s predicted revolutionary crisis of overproduction (combined with penurious worker wages) was averted, both through the twin miracles of cheap mass production and a century of usurious consumer borrowing. A great swath of blue-collar and professional workers, the vast middle class, now enjoys the comforts that their not-so-distant ancestors could only dream of, and not only “two cars in every garage.”

The Future of an Illusion

But Baudrillard’s philosophic and sociological revisionism even leaves these relatively simple critiques behind in the rear-view mirror. In such books as The System of Objects (1968) and The Consumer Society (1970), his overarching project was to cast a cold, unblinking eye on how the modern world has migrated into an illusionary realm of the symbolic while keeping materialist commodification at its tethered core. More precisely, he seizes on the watershed ascendancy of the simulacrum and hyper-reality.

Shunning the tactile, truthful reality of the object-world, the deceived viewer instead turns his or her attention to the reflected or reproduced images of things, frequently to the point of a Freudian fetish. Rather than the classic Marxist concept of worker alienation (exploited man estranged from the goods or services he produces), Baudrillard argues that modernity’s defining alienation arises from the masked schism between the onslaught of images produced, sold, and consumed vis-à-vis the unique “real thing” standing behind them, that is, the subject or referent.

Again, such examples abound in contemporary society, and have since the “age of mechanical reproduction” began in earnest with the invention of photography in the mid-1800s. Not only could a subject be photographed to create an iconic, timeless, yet malleable two-dimensional image, but that image could be reproduced over and over again. With electronic digitization largely replacing analog photography, the duplication potential is practically infinite. When still photography gained another dimension—time—the image became even more lifelike and subject to further confusion between image and referent. Enter the age of the god-like Hollywood movie star, attracting not just spectators but hardcore devotees who are doubly deceived: They are not only seduced by an image (it is not real but an uncanny shadow of sorts) but the image itself is based on a conceit (that “star” is playing a role).

The Medium Is the Message?

This process toward what Baudrillard’s contemporary Guy Debord called the “society of the spectacle” sped into overdrive when television made its way into the hearts (and hearths) of modern man. True, its boxy images paled next to those of the “big screen,” but they were more intimate, portable, and could be conjured up at all hours of the day in one’s own home. Now, says Baudrillard et al., the avid TV watcher could enter into a virtual relationship with any number of TV stars through their characters, indeed so much so that “Jerry Seinfeld” or all those cool, funny New York City Friends could become the viewer’s bosom buddies too. This, of course, comes at the same time that the average viewer might be tuning out his real but unfriendly next-door neighbor.

This pervasive social phenomenon is also associated with the concept of the hyper-real. While the simulacrum ostensibly is indicted as a “cheap copy” of the original (like a knock-off Gucci purse or Rolex watch), a relative degradation, typically, the copy can exceed the original in appeal. How so? Again, consider the modern screen image, whether in cinemas, on TV, or via internet “streaming.” While it is an electronic transformation of the subject/referent, displaced and without substance, the resulting illuminated image is nonetheless charged and “glowing” via the projection and transmission process.

These alluring photogenic values can be further enhanced by the various tricks of lighting and cinematography, like the voyeuristic “close-up” impossible in theater. The viewer can possess the image, even if the original is far beyond reach, in another world. Unmasked of star persona and downsized into a mortal being, more than one screen idol has been met with a fan’s disappointment upon meeting face to face.

By almost any yardstick, the later Baudrillard was a pessimist, if a droll one, with regard to the present human potential for transcendence and Platonic transformation. In books such as his acerbic travel treatise, America (1986), he seems almost gleefully resigned that materialistic, banal, fast-and-furious (and “Disneyfied”) U.S. way of life has triumphed over any romantic or communal idealism that once-upon-a-time budded in late 19th century Europe and America.

Reality Check

Another key facet of the postmodern condition is the sense that, with the fall of the Soviet Union (and Russia’s subsequent regression into an oligarchic, neo-tsarist dictatorship), there is now no meaningful ideological alternative to the global hegemony of mass consumerism and “reification”; the latter meaning the relentless commercial pull that seeks to digest and transform the world into objects to be (mass-)produced, packaged, and sold for a profit. And this process extends far beyond mere manufactured goods or services. From film stars, pop singers, political campaigns, spectator sports, and reality-TV shows to today’s internet “influencers” and web-centered pornography, what’s for sale, what’s infinitely reproducible, is the image, a visual trope or tropes, not the object itself; it is this omnipresent image, all wrapped up and delivered, in one critic’s words, in a “frenzy of the visible.”

One only has to look back into the notorious O.J. Simpson murder case, specifically the 90-minute nationally televised, helicopter-enabled 1994 Los Angeles chase that shadowed Simpson in his white Ford Bronco as he fled his arrest for two brutal slayings, including that of his own wife. Record-breaking numbers of viewers across the nation were rapt, glued to their sets, all watching in real time at a serendipitous, made-for-TV reality show playing out before their them, one only made possible through an omniscient, all-seeing “eye in the sky,” and made lucrative with regular commercial breaks, as if it were a football match.

Two decades ago, on the future of global democracy, Baudrillard glumly wrote that the “idea of freedom, a new and recent idea, is already fading.” Prophetically, this idea is mirrored in many current events. In what no doubt sounds dystopian, Baudrillard underlines such alarming developments by announcing that “reality itself has disappeared,” and as such amounts to a “perfect crime.” In what seems to devolve into a “post-truth,” “deep fake,” “fake news,” artificial intelligence-synthesized era, one can only wonder whether Baudrillard would conclude that mankind itself has simulated itself into a “post-human” era.

Look Harder, Says Jean Baudrillard

Keenly influenced by the seminal French “semiologist” Roland Barthes, Baudrillard’s rogue philosophy boldly grew out of the study of the central importance of signs in society, e.g., the latent yet critical differences between an object’s or image’s denotative (literal, fixed) meanings and their connotative (implied, secondary) meanings. It is here that Baudrillard might start a conversation on how best to defend oneself from this sci-fi-worthy, Orwellian “Invasion of the Images.” In today’s grossly mediated, meme-and-trope-heavy onscreen world, one must always be willing to step back and ruminate, especially on the panoply of visual rhetoric (or deceit) at work in any image, still or moving.

At the very least, one should always bear in mind French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s eye-opening caveat inherent in his famous anecdote when he and a friend were looking out on a river and spied a can floating in the distance. The friend asked, “Do you see that can?” “Yes,” answered Lacan. “Well,” the friend continued, “it doesn’t see you.” Of course, cans can’t “see,” but the point is that just because one gazes at an image or object, in no way does it mean that the image/object is “intended” for the viewer personally—or even that the image/object is aware the viewer exists. Furthermore, via the ability to both record and playback images, allowing “time-shifting,” the viewer stands (or sits) further removed from the new perceptual apparatus. Thus, the postmodern, gaze-gobbling image machine is one gigantic illusion, a sham (if compelling) simulacrum with alienation at its core. Look harder, says Baudrillard, and it will come into focus as a solipsistic, even pathological, delusion.