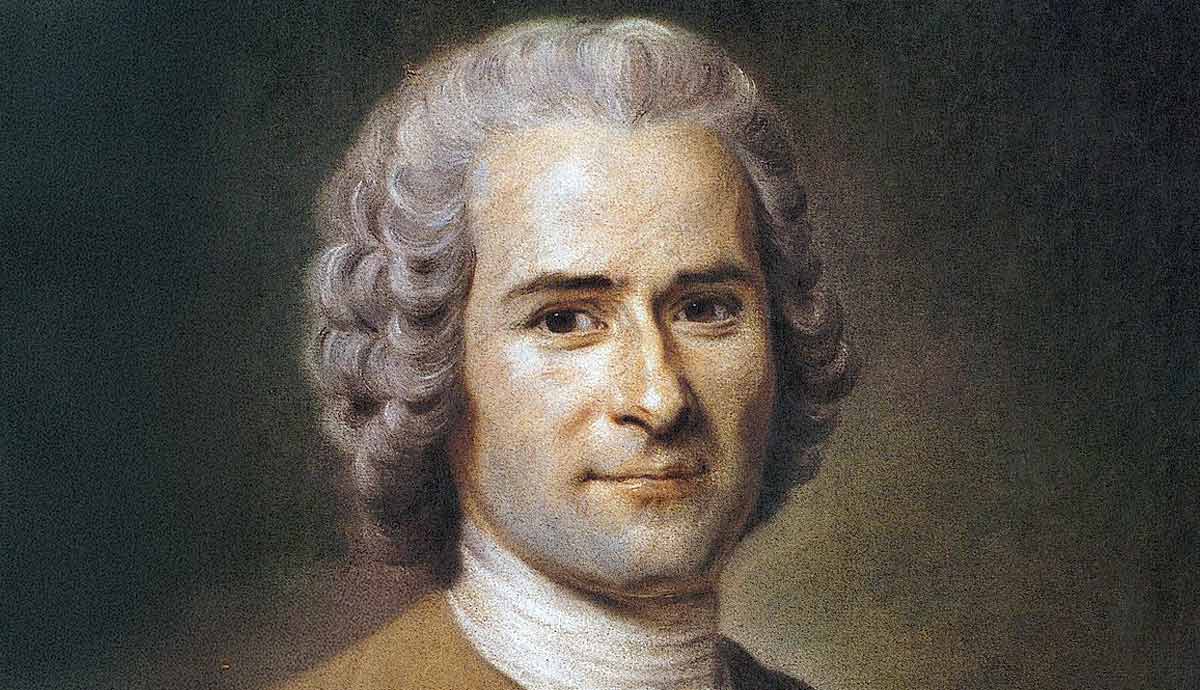

While many believe that civilization and human progress are a good thing and provide us with the best opportunity for freedom, Rousseau disagreed. Contrary to Thomas Hobbes, who argued that life outside of society could never be free but a constant bloody war of all against all, Rousseau, in his famous Discourse on Inequality, claims that life in the state of nature was Edenic, with all human beings being equal. For him, it was leaving the state of nature and becoming ‘civilized’ that introduced inequality into the world.

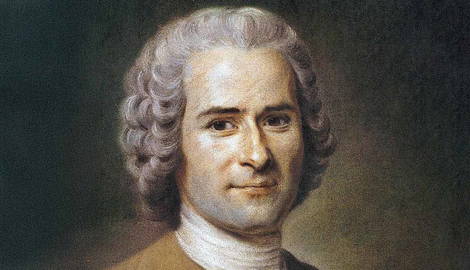

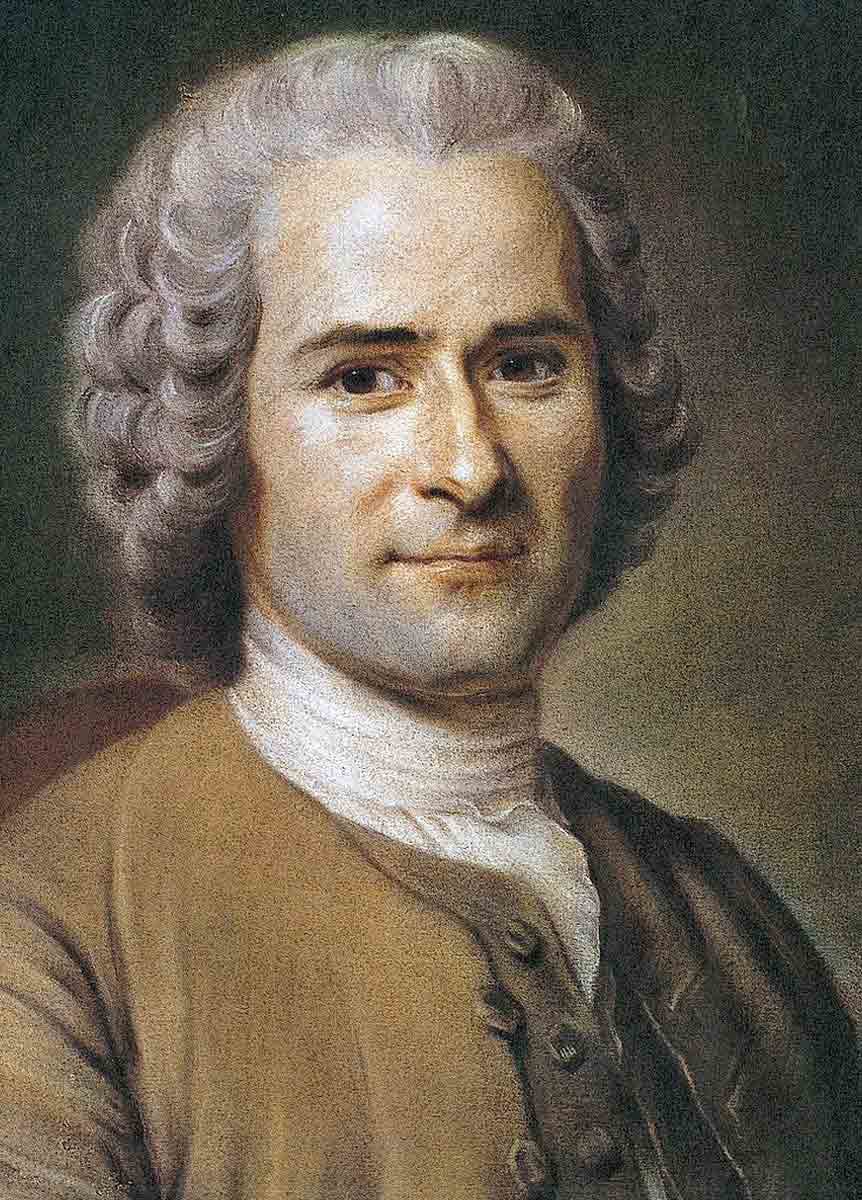

Who Was Jean-Jacques Rousseau?

Most of what we know about Rousseau’s early years comes from his autobiographical text Confessions (1782). He was born in Geneva in 1712 into a middle-class family. His mother died during childbirth, and Rousseau was brought up by his watchmaker father. Unfortunately for the young Jean-Jacques, his father got into trouble for drawing his sword during an argument with a wealthy landowner. Rousseau senior was possibly poaching; he was, according to his son, a keen hunter. As a result, Rousseau went to live with his family on his mother’s side.

When Rousseau was just fifteen, he ran away from Geneva. His disappearance was prompted by his late return to the city, only to find the city gates shut. The motivating factor for his choice to leave may well have been the thought that simply disappearing and following his own fortunes was preferable to the trouble he would have been in for his late return.

After taking shelter with a Catholic priest and following a conversion to Catholicism, Rousseau was introduced to a Catholic noblewoman who later took him as her lover. Sometime afterwards, he moved to Paris, where he met Denis Diderot, best known as the co-founder and contributor to the Encyclopédie. After Diderot was imprisoned in 1749 for his early writings, Rousseau made the journey to Vincennes to visit his friend. It was on this journey that the inspiration for his Discourse on Inequity came to him “in a terrible flash.”

The text was written in 1754 and entered into an essay competition. The question, posed by the Academy of Dijon, was: “What is the origin of inequality among people and is it authorized by natural law?” Rousseau did not win (he had previously won with an essay on arts and science), but his text has gone down in history.

Rousseau on the State of Nature

Rousseau’s argument is that civilization is responsible for inequality. He begins his essay with an appeal to the hypothetical ‘state of nature.’ This is an imagined period of time in which human beings existed before we organized ourselves into societies. It is not really important, for state of nature arguments, whether such a period actually existed. The idea is more of a thought experiment used to test our intuitions about our current situation.

However, it should be mentioned that many philosophers of Rousseau’s time did seem to believe that people they considered ‘primitive’ lived lives very close to that which would have been seen in the state of nature. Thomas Hobbes, for example, believed that native Americans during his time were very similar to people living in the state of nature. Rousseau, in his Discourse on Inequality, talks about people in Costa Rica living very similar lives to those in the state of nature.

We should bear in mind when reading state of nature arguments that the philosophers using the thought experiment were working off very limited knowledge compared to what is known today. Accordingly, some of the claims made by Rousseau about, for example, the day-to-day lives of Costa Ricans should be taken with a pinch of salt. In addition, Rousseau makes some claims that, while certainly inventive, stretch credulity a great deal. For example, in the Discourse on Inequality, he discusses the first human to invent shelter. His argument is that prior to “inventing shelter,” this human must have managed to survive for some time without it. From this, Rousseau concludes that shelter was not actually necessary for early humans—after all, the inventor went their whole life prior to their invention doing without it!

State of nature arguments are best received as thought experiments and not anthropological hypotheses.

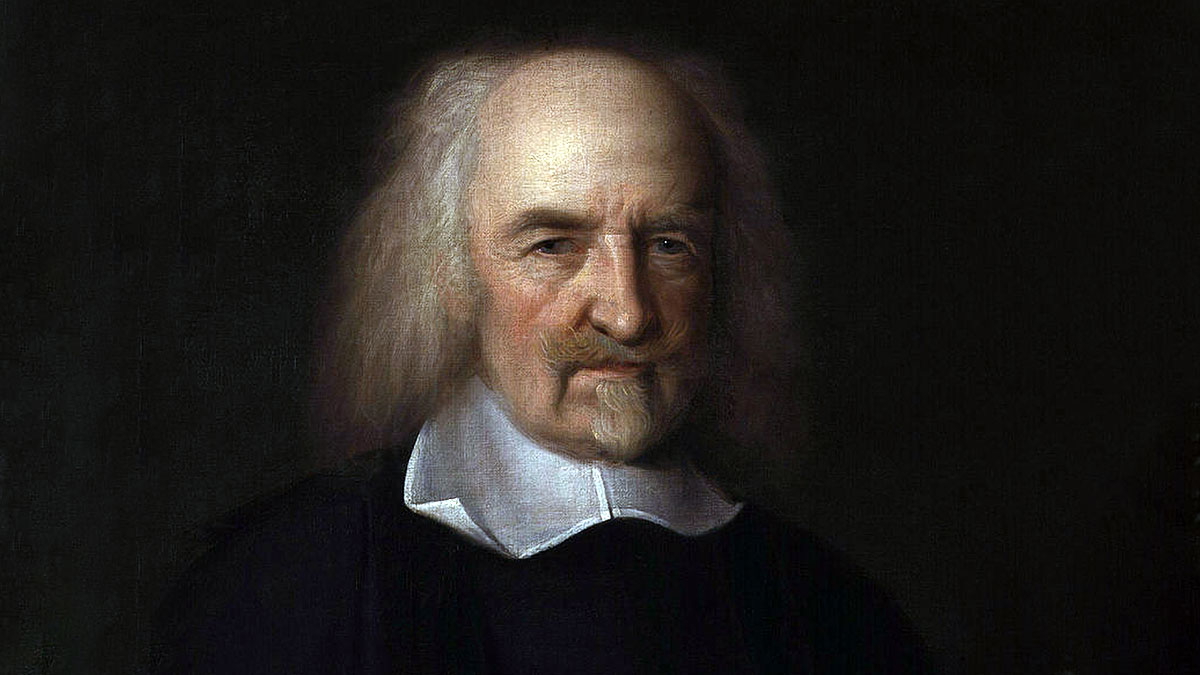

Hobbes’s Conflicting View on the State of Nature

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), in his 1651 text Leviathan, famously said of the state of nature that life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” For Hobbes, life for human beings before civilization was a state of constant war. Because there was no independent judge or standard of law, people would simply fight it out to grab every advantage they could.

The most pressing problem, as Hobbes saw it, was the absence of anyone or any law outside of competing humans. It meant that no one was obligated to keep their promises. The formation of primitive societies and from these to the vast civilizations we have seen since antiquity depend on people agreeing to work together and—most importantly—keeping their word.

For Hobbes, the emergence of a system whereby people were obliged to keep their promises—and by doing so allowed the formation of the first societies—was a crucial breakthrough in human development.

None of the benefits we have today, the freedoms we enjoy in order to live our lives as we do, are possible without the formation of society and the emergence from the state of nature. Consider the following from Leviathan:

“In [the state of nature], there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Rousseau strongly disagreed with Hobbes’ estimation of early humans.

Rousseau’s Idea of Early Humans

Rousseau had a very different idea of early humans than did Hobbes. For Rousseau, who is sharply critical of Hobbes in his Discourse on Inequality, humans in the state of nature had little to fight about. Rather than being a state of war of all-against-all, Rousseau said that for our earliest ancestors, war made as much sense as it would to any other animal.

In his essay, Rousseau says that philosophers like Hobbes make the mistake of looking at people today, who are born into modern societies, and then assuming that humans in the state of nature would think in the same way. Rousseau thought human beings would have been much more like animals. Animals do not, he observed, go to war with each other or bear grudges.

We saw above that Hobbes believed that life in the state of nature would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” In his writings, Hobbes said that human beings would be red in tooth and claw. However, Rousseau questioned this idea. Perhaps, he concedes, immediately after some offense, an individual might react violently.

However, in general, there would be no point in early humans engaging in violence. In his Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau gives the example of dogs that, if hit by a thrown stone, might instinctively bite the stone in ‘vengeance.’ He observes that this need to respond to violence with violence is merely instinctive and passes quickly. Why, Rousseau asks, would early humans have been any different?

For Rousseau, Hobbes exaggerates the potential violence of the state of nature. The Englishman imagines bloody fights over an apple hanging from a tree. Rousseau thinks the more realistic view would be that if two humans in the state of nature both attempted to take the same apple, one would simply walk away and find another tree.

Natural Inequality

We saw above that a dog hit by a stone might briefly ‘seek vengeance’ on the stone. In this situation, the dog is not using reason. If he were, he would know that the stone itself is not to blame for his injury. Here, Rousseau is anticipating a possible objection to his claim that animals do not have pride and seek vengeance.

That is, a dog-owning reader might object and claim that their dog appears to seek vengeance for apparent offences. Rousseau’s response, aimed at cutting off this possible objection, is that the dog’s reaction is very brief and made without reason. The point is that even if early humans acted like dogs in this situation, it would not have any great effect.

Rousseau’s main point is that human beings in the state of nature did not have a sense of pride and therefore did not experience the need to seek vengeance. In opposition to philosophers like Hobbes, who believed life would be a constant war of continual battles for resources and cycles of revenge for perceived harms to their sense of self-worth, Rousseau claims that none of this would even occur to early humans. There would be natural inequalities due to strength and ability, but the effect would be, according to Rousseau, negligible.

Thinking back to the image of two early humans reaching for the same apple, Rousseau says that rather than brutally fight it out, the weaker would simply find another tree. The one leaving would not experience any sense of harm to their self-esteem because they would never have these concepts in mind. In the same way a dog hit by a thrown stone never conceptualizes the ‘insult,’ state of nature humans would quickly forget the conflict. The key point is that pride is a later attitude.

The Beginnings of Pride

The important point for Rousseau is that in the state of nature, humans lack reason. This is why they cannot have pride or suffer harm to their self-esteem. They lack the ideas and thinking power necessary to put complex ideas together, such as shame, guilt, envy, and so on. Instead, they are instinctual and rely on an innate sense of self-preservation. Two powerful instincts Rousseau believes he has identified are a love of self, which he calls amour de soi, and a repugnance of suffering, which he calls pitié.

These instincts, as they occur in human beings, are distinct to them, but versions of these instincts can be found in other animals. That is, horses, for example, have a natural sense of self-preservation and a repugnance of witnessing suffering in other horses. A good example of this would have been the use of war horses in Rousseau’s time. Cavalrymen cannot easily compel their mounts to ride into enemy fire, nor ignore the bodies of fallen horses.

What Rousseau calls amor de soi should be considered as a benign instinct towards the acquisition of food, shelter, and the temporary company of the opposite sex. Amour de soi is later contrasted with amour propre.

Amour propre can be thought of as self-esteem or vanity. For Rousseau, this can only come about when humans compare themselves with others. He believed that in the state of nature, humans rarely made contact with each other. They did not need to. The solitary human had all they needed and all they wanted to survive. In his essay, Rousseau says that the only time humans would seek each other out would be for brief moments of sex. Females were hardier than they are today, as were their offspring. Accordingly, childbirth and child-rearing were only brief affairs. Again, many will raise an eyebrow at Rousseau’s claims.

Property and the Origin of Inequality.

Everything changed, says Rousseau, when the first human began staking out land for themselves. Private property and the cultivation of the land marked the beginnings of human societies and civilization. The great innovation (to the detriment of human beings, according to Rousseau) was for someone to say of the land, “this is mine,” and crucially for others to believe them.

From this point, Rousseau’s account of the formation of societies is much in line with what most of us probably believe. Cultivating the land—land someone had claimed as their own—required people to work together and a division of labor.

Language needed to develop in order for instructions to be made and knowledge to be passed on. Incidentally, Rousseau is very honest in his account of language; he admits to having neither the technical knowledge nor the inclination to acquire it that would permit him to speak with authority on the subject.

Remember that the question Rousseau is addressing asks after the origin of human inequality and wants to know if inequality is natural. His answer is that humans living in nature were equal, but that civilization made them unequal. His main argument comes from the division of labor required by civilization. He says that when people started to become specialized in one thing, tool-making perhaps, and reliant on others for their food and shelter in return for access to the tools they made, then amour propre or envy and pride came into human life.

People started comparing themselves to each other and looked with envy at what others could do and how many resources they were offered for their work. People then leveraged this respect and their resources into power. Power was never an issue in the state of nature, where human beings were all equal. Only in society can there be human inequality.