Kant’s ethical system is one of the most influential and powerful in the history of philosophy. However, other than a few experts, many do not understand its metaethical structure or how all of its parts fit together. Often, this leads students and lay readers to fear engaging with Kant’s ethics. This article will provide an overview of the basic structure of Kant’s metaethical theory, with a special focus on how a complex system of duties can arise from a very simple set of principles.

What Is Metaethics?

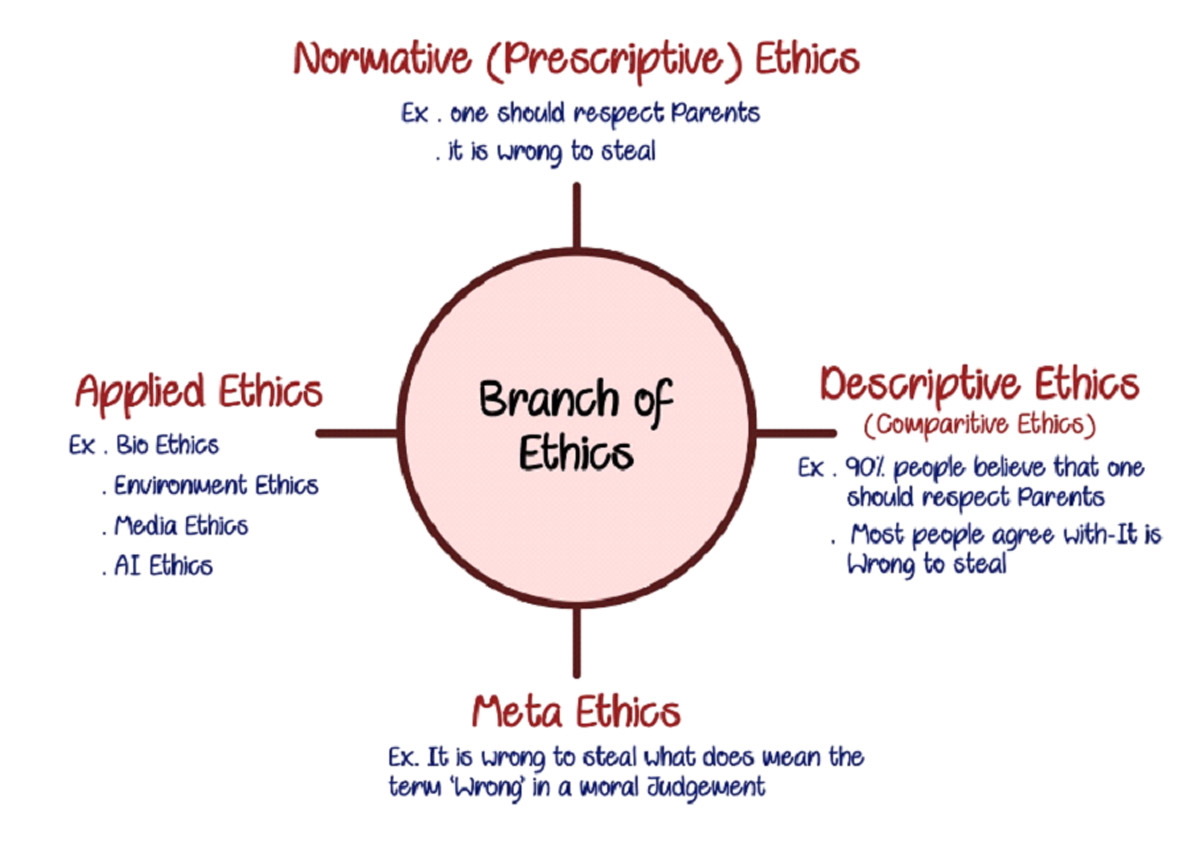

Normative ethics tries to construct general ethical principles and decision-criteria that presuppose the ideas of moral value, goodness, and duty/obligation. Applied ethics applies these general principles to specific dilemmas and topics like abortion or environmental regulation. In contrast to normative and applied ethics, metaethics addresses questions about the fundamental nature of ethical truths, properties, and concepts. What do the words “good,” “evil,” “duty,” “obligation,” and “value” even mean? What divides the truly normative from the merely descriptive? Is it possible to explain why we ought to do x in purely naturalistic terms? What sorts of things actually matter or have value? Why should we care about ethics or morality at all?

Kant’s Metaethical Goals

It is that last question—of why we should care—that concerns us here, though the others will surely also come into play. This is called “the normative question” and has generated intense debates and an ever-expanding metaethical literature. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was one of the first philosophers to address this question, though not in these exact words.

In his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), Kant lays out a theory about the rational origins and foundations of morality. He attempts to explain why human beings have moral duties at all—and why we ought to live up to them—without appealing to mysterious realities beyond the realm of experience. In fact, given that his transcendental idealism (found in his Critique of Pure Reason [1781]) is really a kind of skepticism about reality-in-itself (the “noumenal” realm), Kant wishes to show that moral knowledge is possible despite our inability to know the truth about the nature of metaphysical reality—reality as it is unconditioned by the human mind.

To do so, Kant will posit just a few very simple rational principles and try to build a complex set of ethical duties from them. As Kant puts it, his ethics relies only on the reason shared in common by all humans, not by theoretical speculations (Kant, 2012, 4:403). Theoretical speculation can never confidently reveal reality as it reality is (Kant, 1998, B16-B17, B20, B119, B127).

The Upshot of Kant’s System: Ethics Flows From Rationality

In short, Kant sees ethical and moral truths as truths describing the universal nature of rationality and the demands it makes upon us (Kant, 2012, 4:405; 434). The rational agent, in virtue of being rational (i.e., having “rationality” or a rational faculty), cannot escape the dictates of ethics precisely because these dictates are a necessary aspect of rationality itself. Ethical principles are just rules that our reason naturally and necessarily generates to govern our behaviors, goals, and deliberations.

Thus, to shirk moral duties and be disinterested in ethics would be to neglect the rationality within us, the rational aspect of being human. To be completely a-moral would be to be irrational or a-rational. And who wants to be irrational?

Rational Inescapability

This leads to another way of describing Kant’s answer to the normative question. To ask “why be moral?” or “why care about ethics?” is to ask for rational reasons: reasons to conform our behaviors to some set of moral rules. But for Kant, reasons flow out of rationality. Rationality generates reasons. Thus, to ask for reasons to care about morality is to ask for reasons to care about rationality itself. And to ask for reasons to care about rationality itself is to ask for reasons to care about the source of all reasons. The very question is a request for reasons, and requesting reasons presupposes that we are already interested in being rational.

So, anyone asking the normative question is already interested in morality, even if they don’t realize it. The foundation is already within each human person by virtue of their rationality (Kant, 2012, 4:403). To put it another way, there is no possible rational perspective from which we can dismiss morality; in principle, there could never be a rational reason to place non-ethical interests above the ethical. The demands of morality would be rationally inescapable—so long as one cares about being rational, so too must one care about being moral. The authority and motivational force of morality is just the authority and motivational force of rationality, which we already possess. Morality is a matter of self-regulating by giving laws to ourselves (Kant, 2012, 4:431).

However, to fully understand Kant and the Kantian metaethical tradition, we must understand the logical and rational “mechanisms” that link rationality and ethics. Without more details, we are left with a logical gap between rationality and the various moral rules, prohibitions, and values Kant upholds. For instance, how do we get from the general idea of rationality to Kant’s famous Categorical Imperative?

The Rational Will as Legislative

Kantians are fond of speaking of the will as legislative, and this lies at the heart of Kantian ethics. For Kant, human beings have various desires and goals that they are drawn to, some universally and others idiosyncratically.

The very fact that some rational agent desires x for its own sake is sufficient for x being a worthy goal for that agent (Korsgaard, 2012, p. 227). If I desire x, I have a reason to pursue x (so long as I do not violate rationality by doing so). Hence, Kant claims that his ethical system is centered on the freedom of the moral agent: the moral agent is free to pursue whatever goals they wish, so long as they do so within the minimal constraints or “limiting conditions” of rationality (Kant, 2012, 4:431).

Thus, Kant sees ethics as a set of principles and goals emerging from the interplay of subjective desires and objective (or intersubjective) rational principles. The individual will of the agent determines the particular content of their personal ethical principles and goals, while the rationality universal to all rational agents provides a barebones but significant regulative structure—a structure and set of criteria that apply to all rational agents universally. For instance, Kant’s famous ethical principle, the Categorical Imperative, does not directly tell anyone what goals to pursue or things to care about. Rather, it simply places limits upon the will, which I will get into shortly.

Logical Consistency and the Principle of Instrumental Reason

One way in which rationality provides a regulative structure is through demanding rational consistency. In order to be rational, a person must be logically consistent—contradictions are a prime example of irrationality, per Kant (Kant, 2012, 4:431). The agent cannot simply will whatever goals they wish but must do so in a logically consistent way.

If I will two contradictory things, that is irrational—I must choose only one. This provides us with our first decision criteria: a test for whether we can properly will some end or do some action:

Logical Consistency Criteria: We should never act in a way that involves a logical inconsistency in the will.

Now, the consistency criteria, despite appearing to be minimal, generate some powerful limits upon our will. The first limit is a principle Christine Korsgaard (one of Kant’s most profound interpreters) calls the “Principle of Instrumental Reason” (remember that “end” is an alternative name for “goal”):

Principle of Instrumental Reason: If one wills an end, one is inconsistent unless one also wills the means to that end; if one has reason to will an end, one has reason also to will the means to that end; if one is obligated to will an end, one is obligated also to will the means to that end (Korsgaard, 2012, p. 232).

This may seem complicated at first, but it is rather simple. To “will” something is, by definition, not merely to desire it but to be disposed to bring it about if we can. That is, to will x is to desire x and commit ourselves to making x occur if we have the opportunity to do so. In short, we might say that to will x is more than to merely want x. To will x is to commit oneself to bringing x about.

Defending the Principle of Instrumental Reason

Now, if this definition of willing is correct, then the Principle of Instrumental Reason follows from it simply as a matter of logical consistency. Here is an illustration: it would be totally inconsistent of me to commit myself to learning Russian without also committing myself to doing what it takes to learn Russian. Unless I commit myself to studying Russian vocabulary, doing translation exercises, etc., I cannot really, in any meaningful sense, be committed to learning Russian. At most, I could say that I would like to learn Russian or want to do so, but I could not claim to will to do so.

All that to say: if I truly will x, I must also will whatever it takes to bring x about—I must commit myself to x through committing myself to the necessary steps towards realizing x. If I have some very good reason for willing x, then it must also be the case that I have some reason for willing the necessary steps towards realizing x. And so on… This is all that the Principle of Instrumental Reason states; it is merely an unpacking of the concept of “willing” (Korsgaard, 2012, 218).

And yet, despite its simple nature, this principle is profound. For so long as the rational agent wills some goal, the principle automatically implies that that agent also ought to will whatever it takes to achieve that goal. The agent willing a single non-instrumental (i.e., intrinsically valuable or desirable) goal, when paired with the rational demand for logical consistency, implies that the agent is under a whole host of subsidiary or “instrumental” (i.e., tool-like) moral obligations. The more goals agents will, the more instrumental obligations they have. In this way, the barebones requirements of logical consistency begin to generate a complex moral system.

Rational Necessity and Universalizability

But logical consistency is not the whole story, and not the only regulations rationality places upon the will. Korsgaard takes Kant to posit that the rational faculty demands a kind of consistency that goes beyond merely logical consistency (Korsgaard, 2012, p. 206; 223; 226; 229). That is, in Korsgaard’s interpretation, Kant thinks that logical consistency is one important kind of rational consistency, but not the only kind. Rather, rational consistency also requires “universalizability.”

Universalizability, in its most general sense, refers to a moral rule, value or goal being able to be applied to or made authoritative over everyone, universally. In the Kantian context, universalizability is a kind of consistency: if we are truly rationally consistent, then we must be able to allow that our personal, individual rationales for acting be adopted by others for their actions.

In its most simple form, if we could not, in good conscience, will that everyone else in our situation and with our same reasons act the way we do, then we are being rationally inconsistent. If we could not in good conscience allow this, then we would essentially be giving ourselves a special, ad hoc place of privilege above our fellow rational agents. For why should we allow ourselves to act in ways and for reasons that we do not allow others to? What makes us so special compared to the rest of the human race?

Thus, in order to be rationally consistent, our actions and reasons for acting must be universalizable: we must be able to consistently will that everyone else in our same situation act the same way we are.

One Form of the Categorical Imperative

This rational demand for universalizability is concisely summed up in Kant’s first formulation of the Categorical Imperative, made a bit more clear in contemporary language below:

Categorical Imperative: One ought not do action X in situation S unless one can will the universal endorsement of the imperative (principle): “in S, doing X is permissible or obligatory.” (Kant, 2012, 4:402-403)

This is just the universalizability requirement discussed above. But put in this way, the Categorical Imperative provides not only an important ethical test, but a further source of moral obligations. For the Categorical Imperative rules out a great many ends, acts and imperatives which one might adopt–for one cannot endorse any end, act or imperative as necessary or desirable and permissible which would not be able to be willed as universal.

Further, whatever the Categorical Imperatives rules out, its opposite is now required and obligatory. For instance, if the Categorical Imperative rules out lying, then rational and logical consistency will require us to tell the truth! Thus, a great number of negative/prohibitive and positive duties are generated by combining the Categorical Imperative with the many desires and goals naturally occurring to human beings.

An Alternative Way of Speaking: Value and Goodness

So far, we have described the basic structure of Kant’s ethics as involving rational principles that, when paired with certain goals, generate a number of other duties or “rules.” This can make Kantian ethics seem “stuffy,” overly focused on rules and regulations rather than other important concepts like moral value and goodness.

It may be helpful to close out this article by describing the Kantian metaethical system using these more familiar terms. The wonderful thing about Kantian ethics is that Kant himself recognized our ability to communicate the same content in many different ways (hence why he gave at least three different formulations of the Categorical Imperative [Kant, 2012, 4:431; “The Categorical Imperative,” 2021]).

In short, for Kant and Kantians, each rational agent is able to set for themselves what is good and valuable. The rational agent, through many different influences, finds themselves with certain desires, values and hopes, and the very fact that they desire and value these things for their own sake is enough to make them intrinsically good or intrinsically valuable or worth pursuing for them. This is because the will of the rational agent is itself inherently good, and capable of bestowing good upon other things (Kant, 2012, 4:394). The only requirements placed upon the agent are that they respect the minimal constraints of rational consistency—which they presumably care about anyways, since they are rational agents. Enjoying our desired ends within the constraints of rationality is what Kant calls having a “good will,” and inculcating a good will within ourselves is the only universally binding end and the highest good of life (Kant, 2012, 4:394).

Ethics as Reflective Contemplation; Value as Reflective Success

These rational constraints merely require that the agent is (a) logically consistent and (b) able to universalize their desires and values, so that they do not govern themselves by ad hoc standards.

The agent is able to ensure they are living up to rational consistency simply by reflecting on the three tests or criteria we mentioned above: Logical Consistency Criteria, the Principle of Instrumental Reason, and the Categorical Imperative. If the person reflects honestly on their desires, values and goals, and finds that they are not in violation of any of these principles, they can rest assured that they have successfully lived up to the rationality within them—they have achieved a truly “good will” (Kant, 2012, 4:394).

When an agent does this successfully, and their values and goals are found to withstand these tests, Kantians say that the values and goals in question have achieved “reflective endorsement” (Korsgaard, 1996, p. 97). That is, the rational faculty has endorsed these values and goals as good, valuable, permissible or, sometimes, even necessary for the person (Kant, 2012, 4:432). Those things which would help achieve the goals and values endorsed by the reflective process are also declared to be good, valuable, and obligatory, though only instrumentally so (i.e., good in virtue of their ability to be used as tools to achieve some greater good). These are called “hypothetical imperatives,” “hypothetical duties,” or “instrumental reasons and values” (Kant, 2012, 4:432, 441).

In short, the entire Kantian moral paradigm can be summed up like this: so long as our desires, values, goals and plans survive the process of reflection, and thus earn reflective endorsement, they are permissible and thus good and valuable for us. Certain actions, goals, values and plans could never survive this kind of reflective scrutiny, and these are the only universally and necessarily evil and prohibited things. Everything else is permissible—mankind is free to do whatever it likes.

References and Further Reading

Allison, H. E. (2004). Kant’s Transcendental Idealism. Yale University Press.

Dimensions of Ethics Notes for UPSC Exam. (2023) Theiashub.com.

https://theiashub.com/free-resources/mains-marks-booster/dimensions-of-ethics

“The Categorical Imperative.” (2021, January 18). Open.library.okstate.edu; Oklahoma State

University.

Kant, Immanuel. (1998). Critique of Pure Reason. (P. Guyer & A. W. Wood, Eds.). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1781)

Kant, Immanuel. (2012). Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Cambridge University

Press. (Original work published 1785)

Korsgaard, Christine M (1996). The Sources of Normativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Korsgaard, Christine (2012). “The Normativity of Instrumental Reason.” In Internal Reasons, ed.

Kieran Setiya and Hille Paakunainen, 204-248. London: MIT Press, 2012.

Pasternack, Lawrence (2014). Kant on Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason.

Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Scanlon, T.M (2014). Being Realistic About Reasons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.