Karahantepe is one of the world’s oldest Neolithic sites, dating back as far as 9,200 years. Recently, Karahantepe yielded a very interesting discovery: a decorated stone vessel nested inside a larger one, with three tiny animal figurines (fox, vulture, boar). The figurines were arranged deliberately on a plate in a manner that suggests a carefully staged act with narrative intent. This makes this the earliest story told in three dimensions. TheCollector spoke with Prof. Necmi Karul* to learn about this new discovery and discuss what life would have looked like at the Neolithic site of Karahantepe a few thousand years ago.

*Necmi Karul is the Head of the Department of Prehistoric Archaeology at Istanbul University and Director of the ongoing excavations at Taş Tepeler (which includes sites such as Karahantepe and Göbeklitepe).

“The earliest three-dimensional storytelling.”

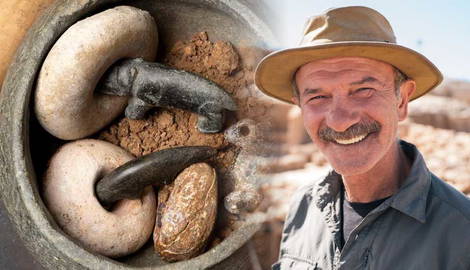

Karahantepe is a Prehistoric settlement in the Taş Tepeler area in Türkiye, the same area where Göbeklitepe was also discovered. The settlement is made up of four communal buildings constructed side-by-side, surrounded by domestic dwellings. One such circular communal building, dating from 9,200-8,800 years ago, included benches and two large ovens for preparing food at certain times. Small standing stones partitioned the space where one bench lay. Within this context, in a bench fill of red sterile soil, the excavation team made a unique discovery. Underneath the bench fill, they found stone plates and vessels with geometric and animal decoration (gazelle, fox, wild sheep) alongside human/animal figurines and animal bones. Inside a large vessel, the team discovered a smaller vessel, containing three stone rings and three animal figurines, each about 4 cm tall. The animals’ heads fitted into the stone circles. The small vessel was placed on a plate and nested inside a larger vessel.

But what makes these specific animal figurines so unique? Besides, there are several animal reliefs in Karahantepe, carved on T-shaped pillars (see note below) and benches, as well as many examples of prehistoric cave paintings featuring animals. Necmi Karul explains:

“All these [the cave paintings and pillars and benches] are two-dimensional. For the first time, we have a case of three-dimensional storytelling. They inserted the figurines into the circles and placed them inside one vessel that was then placed on one of the plates and inside a larger vessel. This means that their arrangement was organized. It was not an accident.

They also chose specific animals: fox, vulture, and boar, which are also the animals you commonly see on the pillars. This makes the findings different than everything else we have found until today. Therefore, I can call this the earliest three-dimensional story telling. And in this context, we have also some vulture, leopard, and fox bones with their pelt together. Perhaps there are other bones too. Our zooarchaeologist continues to work on the bones.”

Note: The T-shaped pillars at Karahantepe and Göbeklitepe are named after their unique “T” shape. According to Prof. Karul, these served functional purposes as columns that supported roofs. However, they also bear anthropomorphic features, indicating that they symbolically represented the human body. Also, their surfaces served as narrative surfaces: “blackboards” filled with reliefs of animals, humans, and geometric motifs that residents could see while seated inside.

Lost Mythologies That Kept a Society Together

But if this is a story told in three dimensions, then what is the story about? In Karahantepe as well as in Göbeklitepe, animals and humans are depicted on carved stones and pillars. Prof. Karul believes that these images depict a mythology that is now lost but was understood by the people who built the Taş Tepeler sites.

“We are sure that animals have different meanings for different societies. These animals depicted in Karahantepe certainly held meanings to the people that created them. Otherwise, it wouldn’t make any sense to depict them on the pillars. Some pillars present scenes composed of animals and geometric motives. Some even have human figures. For example, a pillar from Göbeklitepe has a headless man on the pillar with two cranes and other geometric motives. This might be a reference to mythological stories that the societies that built these places wanted to remember. If these were indeed mythological stories, the people going inside the building, would know them. This means that there would be storytellers interpreting the stories and keeping them alive as well as the artists who curved the figures on the pillars.

In the beginning of sedentary life, the people start to live together in large populations. Before, they used to live in groups of 20-25 people that were hunter-gatherers and nomads. But as they settled down and hundreds of hundreds people began living together they erected monumental buildings that could bring the people together. And these stories, told in the pillars and the figurines, helped keep the societies together.“

Hunter-Gatherers Who Settled Down?

In the earliest Taş Tepeler phases, there is no evidence for domesticated plants or animals: people are still hunter-gatherers but sedentary. This goes against the traditional view that holds that agriculture ended nomadic life. Now, archaeologists know that the so-called Agricultural or Neolithic Revolution is a term that should be used with caution. Settlements like Karahantepe demonstrate that groups of hunter-gatherers abandoned nomadic life to come together in sedentary societies. As Prof. Karul puts it, “they were still hunter-gatherers, but they preferred the sedentary life.”

But how could a large sedentary population be sustained without agriculture? The answer lies in the hundreds of hunting traps that have been discovered around Karahantepe. “This means, most probably, that they had strategies and techniques for controlling herds of animals using these traps,” says Prof. Karul. This way, they did not have to move around to secure their food.

By settling down, the hunter-gatherers of Karahantepe developed a new relationship with their environment.

“Some animals were good for domestication, some not. After 1,500 years, we observe some cultivation and domestication elements in these same settlements. Therefore, we can say that when they settled down, they were still hunter-gatherers. However at the end of the early Neolithic, they have become real villagers; they have domesticated crops and animals.”

The Challenges of Excavating a Neolithic Site

“The works will continue here for at least 50, maybe 100 years. I have less time,” says Prof. Karul as he talks about the excavations in the southern province of Türkiye’s Şanlıurfa area. There is also significant interest from institutions outside Türkiye. In total, 36 academic institutions from all over the world have been involved, to varying degrees, in the research conducted at Taş Tepeler.

“We came together because of a certain question, because of the will to understand the early sedentary life, early domestication and agriculture. Today everyone continues the sedentary tradition that began with the Neolithic. That’s why it’s such an important Era to study.”

There are roughly 220 people (archaeologists, specialists, students, and workers) working at around 10 sites in Taş Tepeler. This makes it one of the largest archaeological undertakings of its kind. The practicalities are far from ideal, though. With summer temperatures exceeding 50°C (122°F), the team has to be on site as early as 4 am.

Taş Tepeler is more than the sum of the archaeological excavations that are taking place at its sites. According to Prof. Karul, it is a multidimensional project based on the following four pillars:

- Archaeology: Surveying and excavating across the region.

- Environment: Using paleo-geography and modern ecology to understand landscapes then and now.

- Heritage management: Göbeklitepe saw close to a million visitors. The volume of visitors is significant and careful planning is required as the other sites will open to the public in phases.

- Ethnography: Documenting local villages, tools, and foodways that can not only inform prehistoric interpretation but also provide an opportunity to record living traditions.