While its eastern neighbour Aragon sought to forge a maritime empire across the Mediterranean, the armies of Castile marched up and down the Iberian peninsula to drive out the Moors, who had ruled for several hundred years. Their successes laid the foundations for the unification of Spain in the 15th century.

Founding of the Kingdom

Before it became its own independent kingdom, Castile was a county under the control of the Kingdom of León. The name Castile literally meant “land of castles,” and the county contained many defensive fortifications to prevent the further expansion northward of the Moors in al-Andalus. It was a crucial borderland between the Christian and Muslim worlds.

In the 9th and 10th centuries, Castile defended against attempts by the Moors to conquer the rest of the Iberian peninsula. Its people became imbued with a spirit of defiance and militarism. This in turn fueled a sense of independence, leading several Castilian counts to start acting independently from their royal masters in León. This was especially the case under Count Fernán González of Castile, who ruled from 931-970.

González united the Castilian lands and manors, making him the strongest Castilian ruler to date. He secured the right for his title to be inherited by his sons, enabling his family to build a secure power base. By the 11th century, Castile was evolving into a formidable actor in the Iberian peninsula. Not only was it challenging other Spanish kingdoms, it was also facing down the Moors to the south. This set the stage for its ruthless expansion in the peninsula.

Union With León

Castile’s first major expansion came with its union with León. In 1037, Ferdinand I of Castile, the son of King Sancho III of Navarre, inherited León through his marriage to Sancha of León. He also defeated her brother, Bermudo III, in battle, solidifying his control over the two kingdoms. This briefly made Castile the strongest Christian kingdom in the Iberian peninsula.

However, subsequent chaos between the joint kingdom led to the dissolution of the union after Ferdinand’s death. Throughout the rest of the 1000s and 1100s, Castile and León were repeatedly unified through marriage or conquest, only to have the union fall apart again. Both kingdoms had different political and social cultures, making unification a serious challenge. Assassinations of nobles and courtiers were a routine occurrence.

By 1230, Castile and León were finally united on a permanent basis after Ferdinand III of Castile inherited León from his father Alfonso IX. Through skilled administration and a deft diplomatic touch, Ferdinand managed to keep the two kingdoms united and combined their administrations into one while respecting both Leónese and Castilian rights and customs. Once these two kingdoms were permanently united, the Castilians began driving southwards in an effort to push the Moors out of the peninsula once and for all.

Castilian Expansion

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Castile continued to put itself on the map as a formidable force. In 1085, Alfonso VI wrested control of the key city of Toledo from the Moors, a vital victory in the fight against al-Andalus. They followed this success with a drive southwards beyond the Duero River, consolidating their gains. As they had in prior centuries, the Castilian nobility built additional castles to fortify their lands and protect themselves from Moorish counterattacks.

Alfonso VIII not only had to contend with the Moors but other Christian states jealous of Castile’s power. In 1177, he seized Cuenca alongside Aragonese forces from the Almohad Caliphate, continuing his relentless push into Moorish territory. In 1212, Castile devastated Almohad forces at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa. This victory opened the Guadalquivir valley to Christian conquest and led to the retreat of the Moors southward.

Through the rest of the century, Ferdinand III, who now ruled over both Castile and León, conquered several more cities in the Andalusian heartland including Córdoba, Jaén, and Seville. This resulted in significant demographic changes as the king of Castile now had a large number of Muslim subjects. The only part of Iberia that remained under Islamic control was Granada, ruled by the Nasrid Emirate.

House of Trastámara in Castile

Castile’s expansion was punctuated by periodic bouts of internal chaos. From 1366 to 1369, Castile had a civil war that pitted Peter I “The Cruel” against his half-brother Henry II of Trastámara. Aided by French and Aragonese forces, Henry II destroyed Peter’s forces and killed him, becoming king in his place. This enabled the House of Trastámara to take power and end years of chaos in the Castilian realm.

Henry II stabilized the kingdom but increased noble privileges to secure his position on the throne. His successors sought to centralize power, but were at times weakened by court intrigue and personal rivalries. Nonetheless, the Trastámaras played a pivotal role in European politics. They went back and forth in supporting England and France during the Hundred Years War.

Later in the 15th century, the dynasty faced major challenges. When Henry IV died in 1474, his succession was contested, leading to another civil conflict known as the War of the Castilian Succession. Supporters of his daughter Juana (also known as “la Beltraneja”) fought several battles against Isabella, Henry’s half-sister. Isabella’s supporters prevailed, ensuring that she became the Queen of Castile. This laid the groundwork for the dynastic union between Castile and Aragon and the unification of the modern nation of Spain.

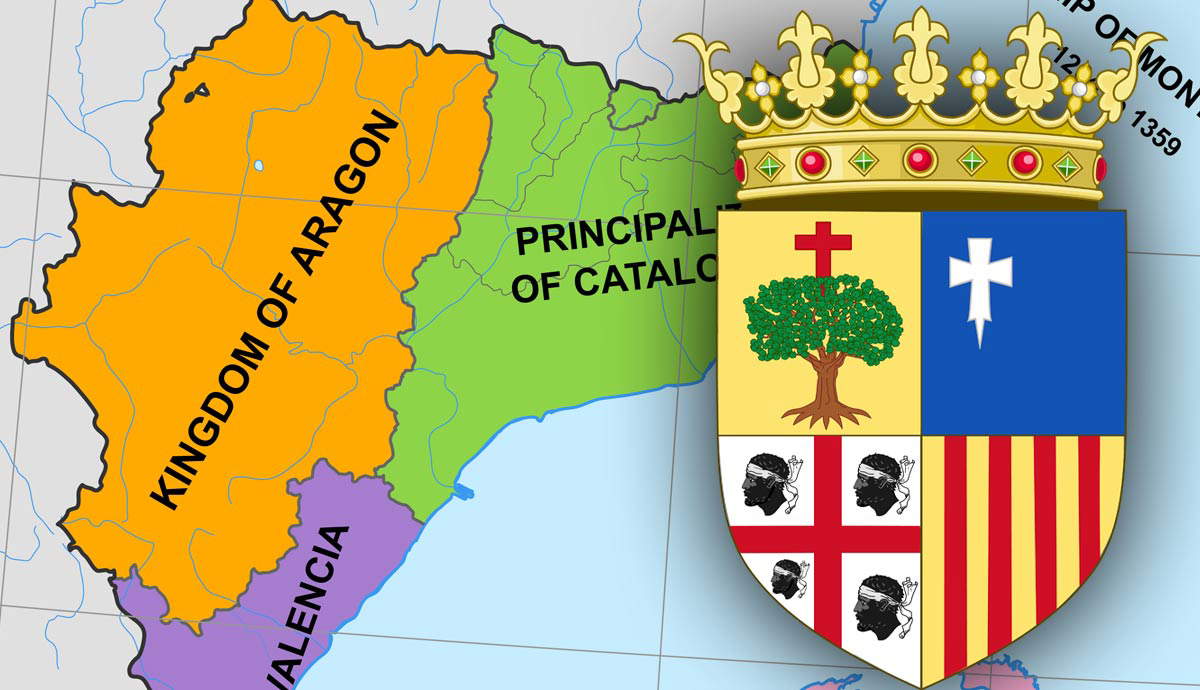

The Unification of Spain

Before claiming the Castilian throne, Isabella married Prince Ferdinand of Aragon in 1469. After Ferdinand became King Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1479, the couple jointly ruled over the first unified Christian Spanish monarchy. Ferdinand and Isabella’s realm included the Aragonese possessions of Sicily, Sardinia, southern Italy, and their domain would soon expand into the Americas under Castilian initiative.

Following the dynastic union, the crowns of Aragon and Castile retained their political institutions. However, both Ferdinand and Isabella curbed the power of the parliaments in both kingdoms, leading to an increase in royal power. This angered some Castilian nobles who resented the loss of authority. Despite internal tensions, Ferdinand and Isabella successfully launched a campaign to oust the Moors from Granada in 1492. Once this was accomplished, Castile and Aragon controlled the entirety of the Iberian peninsula except for Portugal.

Castile’s relentless drive to the south made it one of the most formidable military powers in medieval Europe. Despite its internal power struggles, Castile made a name for itself as an aggressive state with a reputation for innovation and ruthlessness. Once it combined its skill of marching against its enemies on land with Aragon’s naval power, Castile became one of the strongest kingdoms in the medieval world.