Language is alive. It changes and evolves with the cultures that use it, reflecting their values and unique aspects of daily life. Considering how the slang of younger generations can seem indecipherable to older folks, it’s no surprise that the English spoken in Medieval times can almost seem like a foreign language. That said, many phrases we use today have Medieval origins, some amusing and others frankly disgusting.

1. The Wrong End of the Stick

When we say someone has the “wrong end of the stick,” we mean that they have misunderstood something. But the phrase has frankly disgusting origins. In the Medieval era, public toilets were long stone benches with carved holes side by side for users. There was no toilet paper, but a sponge that soaked in vinegar or salt water between uses, attached to a communal stick that was passed along. It was rather unpleasant if you accidentally grabbed the wrong end of the stick.

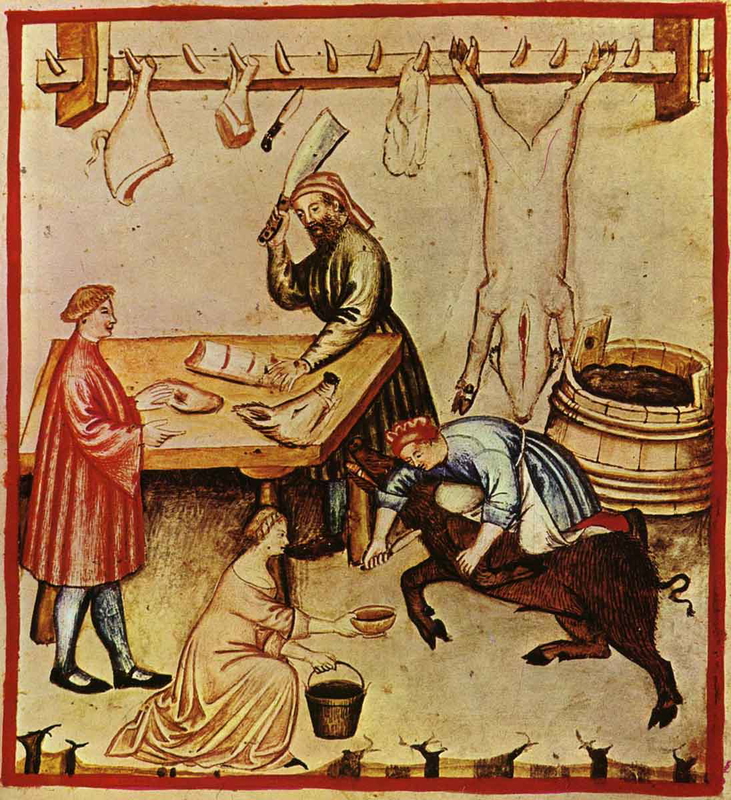

2. A Pig in a Poke

If you went to a Medieval market, you would receive your animal or animal meat from the butcher inside a cloth sack called a poke. When purchasing, you had to ensure that you received what you expected in your bag. Those who didn’t and waited to get home to open up their bag could be disappointed and find that they had been given something much less appetizing inside. This gave rise to the phrase “pig in a poke” as a warning against accepting something without identifying it as what you expected.

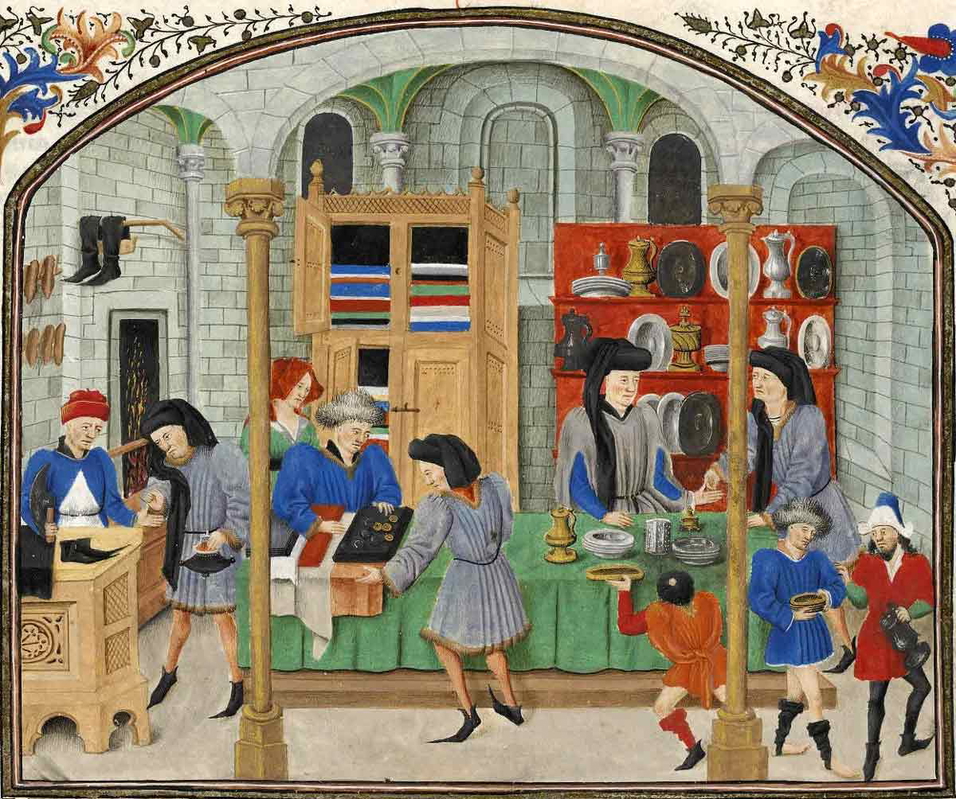

3. Eat Humble Pie

When you must apologise for something when you don’t really want to, we sometimes call this “eating humble pie.” But while this phrase represents swallowing your pride today, in the Middle Ages, it literally meant eating offal pie. When animals were butchered, the best pieces went to the wealthy nobles, while the leftovers, such as the liver and lungs, were minced up to make pies for poorer folk. These were called “umble pie” in England, adapting the Norman-French word “nombles,” which means dear innards. Eating these pies became a metaphor for being put in your place.

4. By Hook or By Crook

When we say “by hook or by crook” today, we mean achieving something no matter what and by whatever means necessary. This phrase can be traced back to the 14th century, when most forests were owned by the crown. As such, while commoners were allowed to enter forests to collect things such as firewood, they were specifically barred from cutting branches from fallen trees using a billhook or pulling them down with a shepherd’s crook. Since this would have been difficult to monitor, many peasants likely got away with gathering extra wood using these illicit tools, obtaining what they needed by fair means or foul.

5. Caught Red Handed

Today, we use the phrase “caught red-handed” to indicate that someone has been caught in the act of doing something. But the term was initially coined because laws in 15th-century Scotland stated that a person could only be convicted if they were caught in the act or with the blood still on their hands, turning them red. This could apply to murdering a fellow man, but more usually applied to poaching and killing livestock. The phrase remains popular today because Sir Walter Scott used it in his popular 1819 novel Ivanhoe.

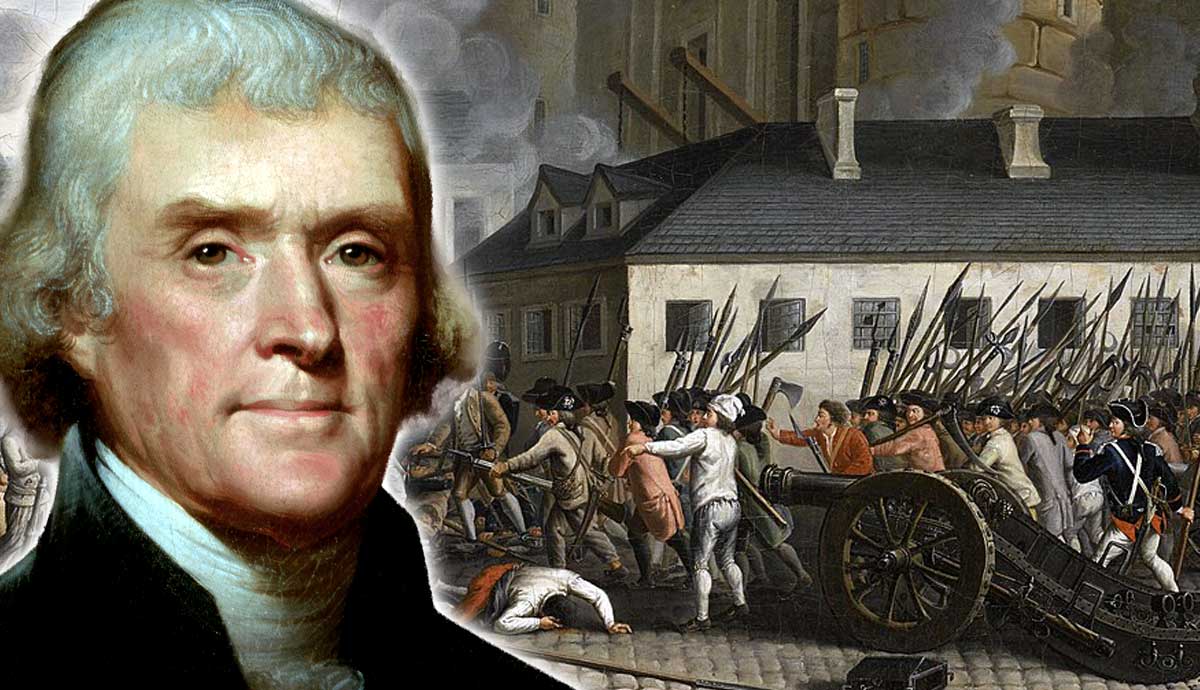

6. Drawn and Quartered

The phrase “drawn and quartered” reflects the bloody sense of humor of the Medieval era. One of the most common forms of execution was to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. This saw a person hanged but cut down before dying so that they could suffer their genitals being removed, bowels extracted and burned, and then beheaded. The head was then displayed on a spike. In 1305, when William Wallace, of Braveheart fame, was killed, his body was famously divided into four parts. Today, we say that someone should be “drawn and quartered” when they need some serious consequences.

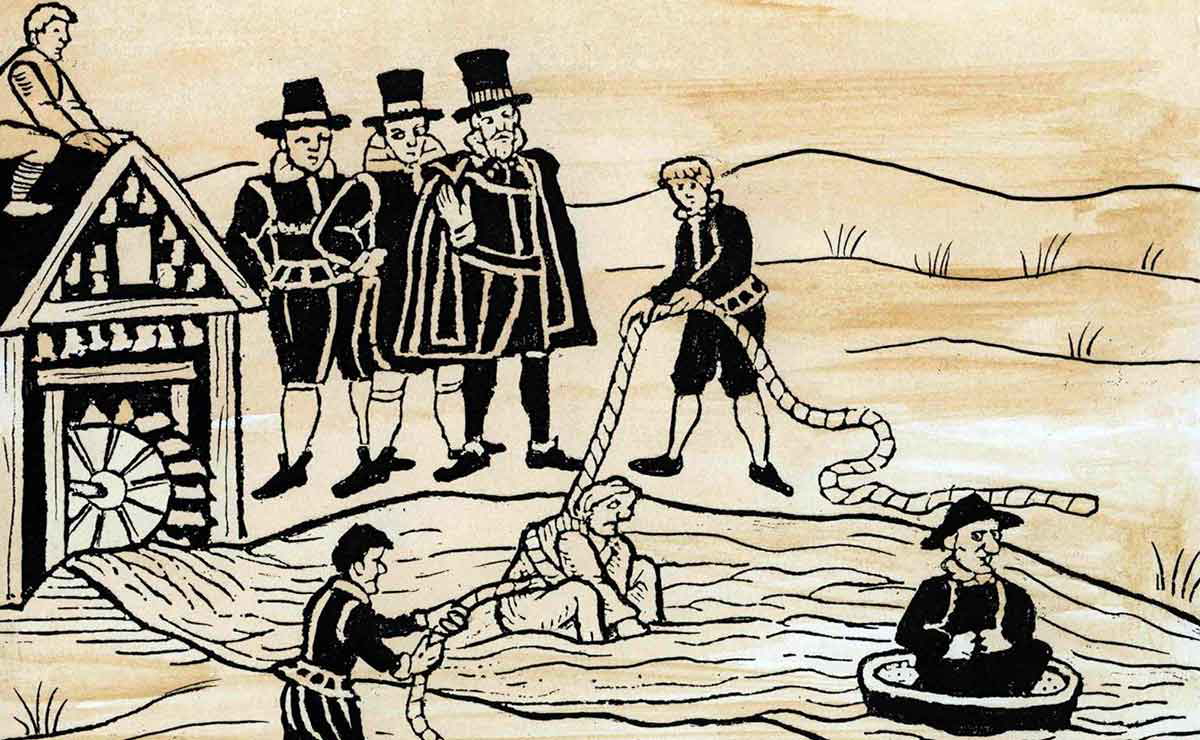

7. Sink or Swim

The phrase “sink or swim” also has violent origins. In the Medieval era, there was a belief in signs from the divine. Trial by ordeal could allow the divine to indicate if a person was guilty or innocent. Unfortunately, the general rule was that the innocent would sink, and therefore possibly drown, while the guilty would float, pushed out of the baptismal waters. Today, the phrase means jumping in the deep end and seeing what happens: success or failure.

8. No Man’s Land

“No man’s land” has been used since World War I to describe the land between the trenches of the two opposing sides. It has become more broadly popular to refer to a dangerous area where men fear to tread. But it is actually an older Medieval phrase from the 11th-century Domesday Book, written “nanesmanesland” to describe uninhabited and desolate areas, such as waste grounds (garbage dumps) outside cities.

9. By My Troth

The word “troth” meant “true” in Medieval England, so “by my troth” just means “by my truth.” In the 14th century, the phrase was commonly used to swear that what a person was saying was true. It appears frequently in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in which it appears as a common, everyday oath. It remained popular for centuries and even appeared in Shakespeare, such as in Henry IV, Part Two.

10. Memento Mori

“Memento Mori” was a Latin phrase commonly used in the Medieval world, reminding people that death is inevitable: “remember that you must die.” It was used to chastise, reminding believers that life could be over at any moment, and to live righteously. It became a popular phrase in devotional art, appearing in macabre scenes alongside skulls.

11. By God’s Bones

“By God’s Bones” was a popular way to swear in Medieval England, referring to the physical remains of Christ. Sometimes the word bones was replaced with eyes, nails, or something else. It was used as a kind of blasphemous oath, taking the lord’s name in vain in the most vulgar fashion. It was considered doubly offensive because of how seriously people took oaths, as communities were built on trust.

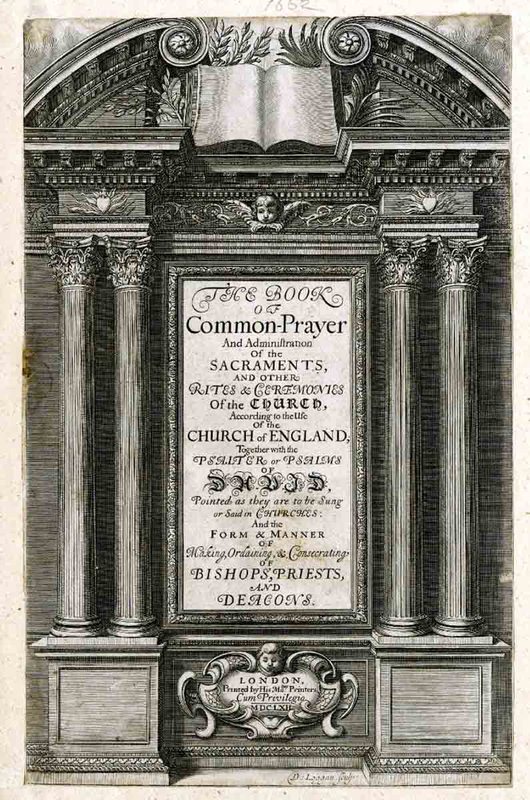

12. The World, the Flesh, and the Devil

In the Middle Ages, “the world, the flesh, and the devil” were the three great enemies of the Christian soul, representing external, internal, and spiritual temptation. This phrase was used repeatedly in sermons and theology, making it a widely familiar Medieval idiom. It was used as late as 1662, when it appears in the Book of Common Prayer.

13. Blood is Thicker Than Water

The common phrase “blood is thicker than water” suggests that the bonds of family are stronger than those of any other relationship. This phrase can be traced back to 13th-century Germany, where it was used to suggest that water could dilute blood ties, possibly referring to the potential impact of baptism. By the 15th century, the phrase was used in England with a reversed meaning, because while water leaves no mark, blood is hard to wash off.

14. One Bad Apple

We often use the phrase “one bad apple” to refer to the impact that just a small amount of negativity can have. The original phrase is “one bad apple spoils the whole barrel,” and specifically refers to fruit storage. If you accidentally place a bad apple in a barrel, it can quickly spread and ruin the rest of the produce. It became a metaphor for Juman behavior, with Geoffrey Chaucer referring to a “bad apple” in his The Cook’s Tale, to describe someone who causes problems for others.

15. More Irish Than the Irish

During the 12th century, the Normans started to invade and settle Ireland. While they formed a noble upper class, they also became deeply immersed in local customs and culture. This concerned the Anglo-Norman leadership back in England, so by 1366, the Statutes of Kilkenny were introduced to limit cultural assimilation. The phrase “more Irish than the Irish” was coined to refer to those who enthusiastically migrated and then adopted the local culture.