Christian history has seen many Church councils where matters of doctrinal concern have been discussed and clarified. Some, like the First Vatican Council which established the doctrine of Papal Infallibility when speaking ex-cathedra, have little bearing on Christianity as a whole. They speak to Catholic Theology specifically. Other councils, however, have become the backbone of most Christian denominations’ theology. Their creeds are still subscribed to today, or their decisions impact interaction and collaboration between churches. So, which councils impacted Christian doctrine beyond the confines of the Roman Catholic Church?

1. Council of Nicaea (325 CE)

Persecution of Christian Churches came to an end with the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, and the freedom brought to light that some churches taught that Jesus was not God. This view was promoted by a priest from Alexandria called Arius, among others, and was called Arianism.

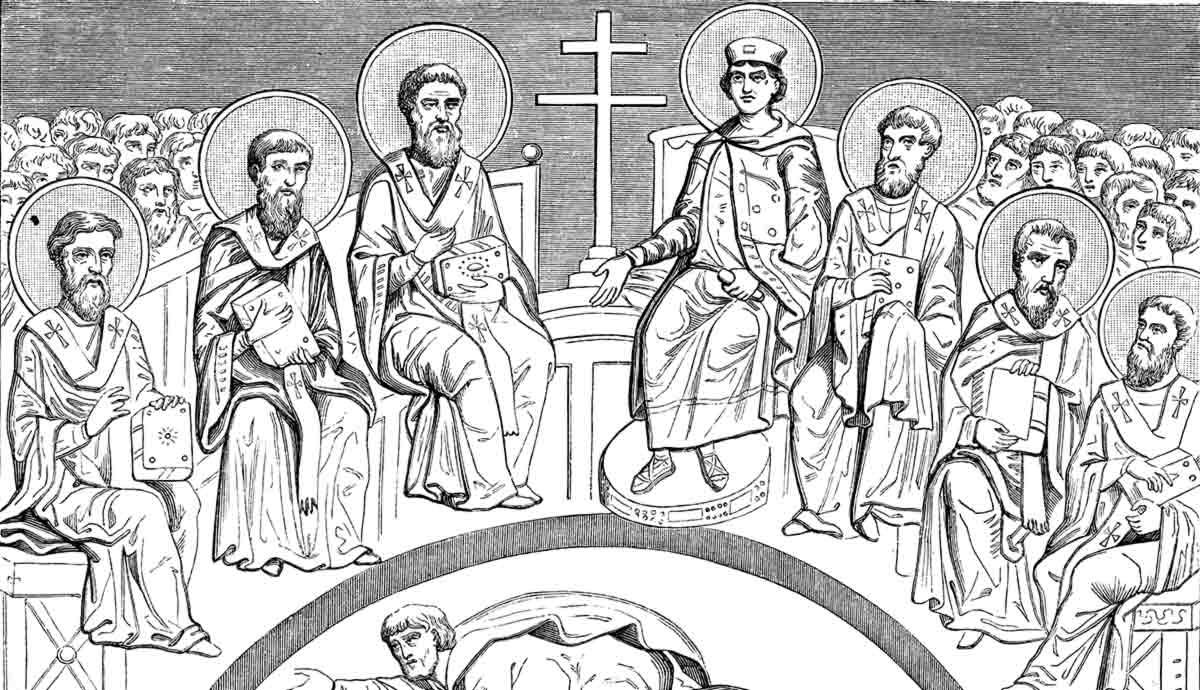

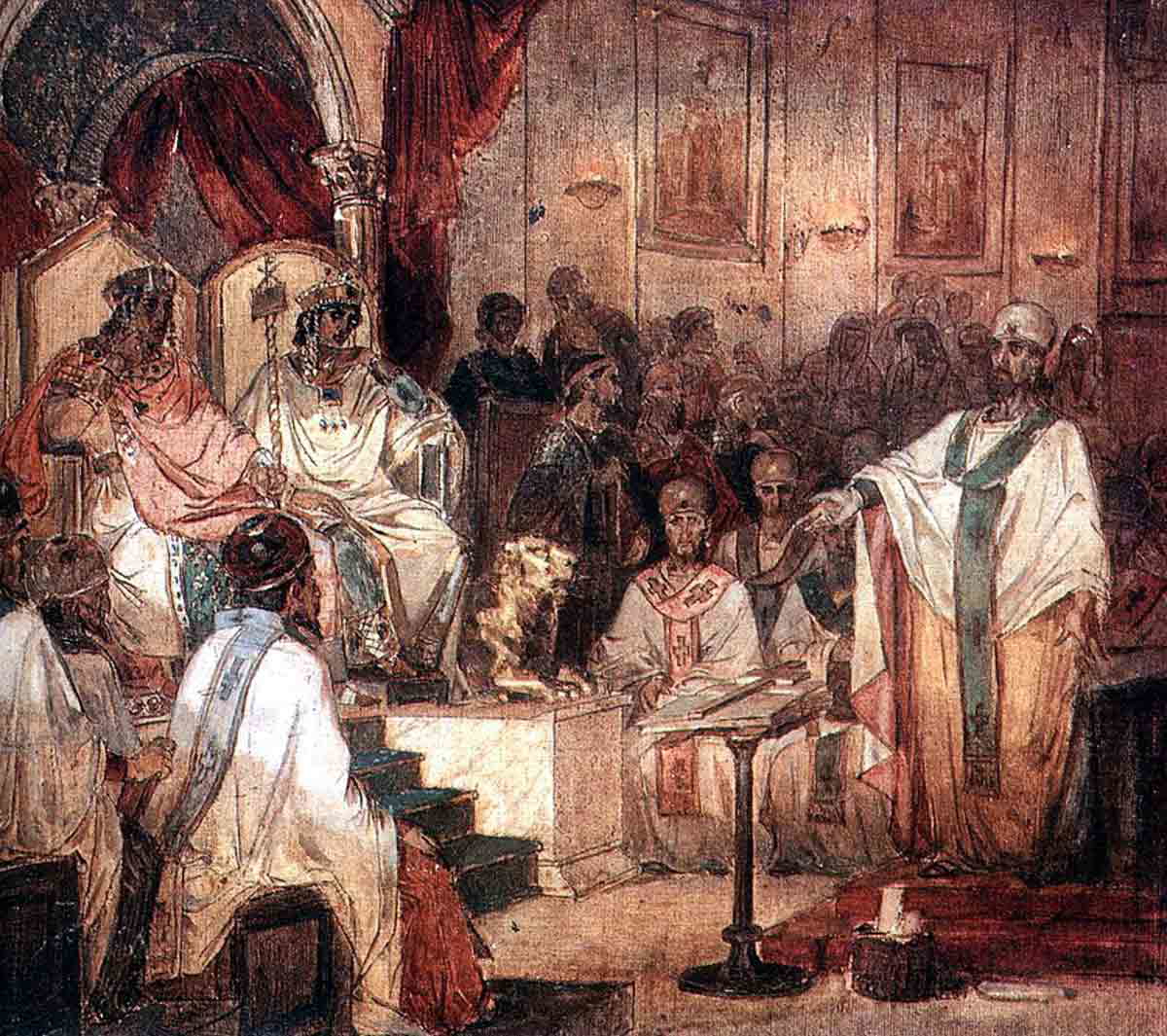

Emperor Constantine convened the first ecumenical council in Nicaea in 325 CE to address the Arian controversy and decide on the divinity of Christ. 318 bishops attended the council. In the end, the bishops had to vote on the matter and only two dissented, resulting in their excommunication. The majority concluded that Jesus is “of one substance with the Father” (homoousios). It resulted in the Nicene Creed, which to this day is a cornerstone of Christian Trinitarian theology.

This council and creed were not the end of Arianism. It seems many bishops who attended the Council of Nicaea and voted in favor of the Nicene Creed, actually taught Arianism in their native land.

2. Council of Constantinople (381 CE)

The language of the Nicene Creed was not ideal and left the opportunity to misinterpret what the Fathers of Nicaea aimed to convey. After the death of Constantine I in 337 CE, Constantius II became co-emperor of Rome with his two brothers. He leaned more toward Arian beliefs and gave authority and prominence to Arians over the Nicene Christians. Arianism, therefore, flourished in Roman Churches.

Apollinaris of Laodicea, likely in an overreaction toward Arianism, taught that though Jesus had a human body, he had a divine mind and will which overshadowed his humanity. When Theodosius I became Emperor, he convened the First Council of Constantinople in 381 CE to address Macedonianism, which is the denial of the divinity of the Holy Spirit. Macedonianism, in addition to Arianism, became a topic of debate in Eastern Christendom which needed to be resolved.

The Greeks claimed the council was ecumenical, but only 150 Eastern bishops were summoned to attend the council and they tended to be friendly toward Meletius, the bishop of Antioch who presided over the council initially. He passed away during the council and was replaced by Gregory of Nizianzen. The council condemned Arianism and other contemporary heresies related to the nature of Christ and confirmed the divinity of the Holy Spirit. As such, the council established the Trinitarian doctrine which has been a feature of most Christian Churches throughout history.

The council addressed several other issues as well, such as declaring that the bishop of Constantinople had pre-eminence over all other bishops except the bishop of Rome. Though the Bishop of Rome, Pope Damasus I, did not accept all the canons of the council, he did accept the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed on the Trinity. Eventually, the council came to be regarded as ecumenical in the East and the West. It was the Second Ecumenical Council in Church history.

3. Council of Chalcedon (451 CE)

The Council of Constantinople was not the end of debates about Jesus. Church Fathers continued to debate the nature of Christ while some refused to accept the canons of previous councils. Arianism remained an issue with some bishops holding to the doctrine that the Church hoped would have been settled a century earlier.

The Council of Ephesus, held in 431 CE failed to bring resolution to ongoing debates and the Emperor Marcian called the Council of Chalcedon, located in modern-day Turkey, in 451 CE. It was the largest of the early Church councils, attended by about 520 bishops and representatives from across the Christian world. It was the Fourth Ecumenical Council in Christian history.

The Council of Chalcedon was tasked with clarifying the doctrine of Christ’s nature, among other things, but did not aim to create a new creed. They concluded that Christ had two natures, fully divine and fully human, in one person. Scholars refer to this view as Chalcedonian Christology. The Chalcedonian Definition became a key doctrinal statement for many Christian traditions. The Council of Chalcedon condemned Monophysitism, which taught that Christ only had one nature.

Far from bringing unity to Christianity, the findings of this council were the precursor to the eventual split between Latin and Orthodox Christianity around 600 years later.

4. Third Council of Constantinople (680-681 CE)

Monothelitism held that though Christ had two natures, he had only one will. Monenergism refers to the belief that Christ had one energy while having two natures. These two ideas were issues of debate in the 6th and early 7th centuries.

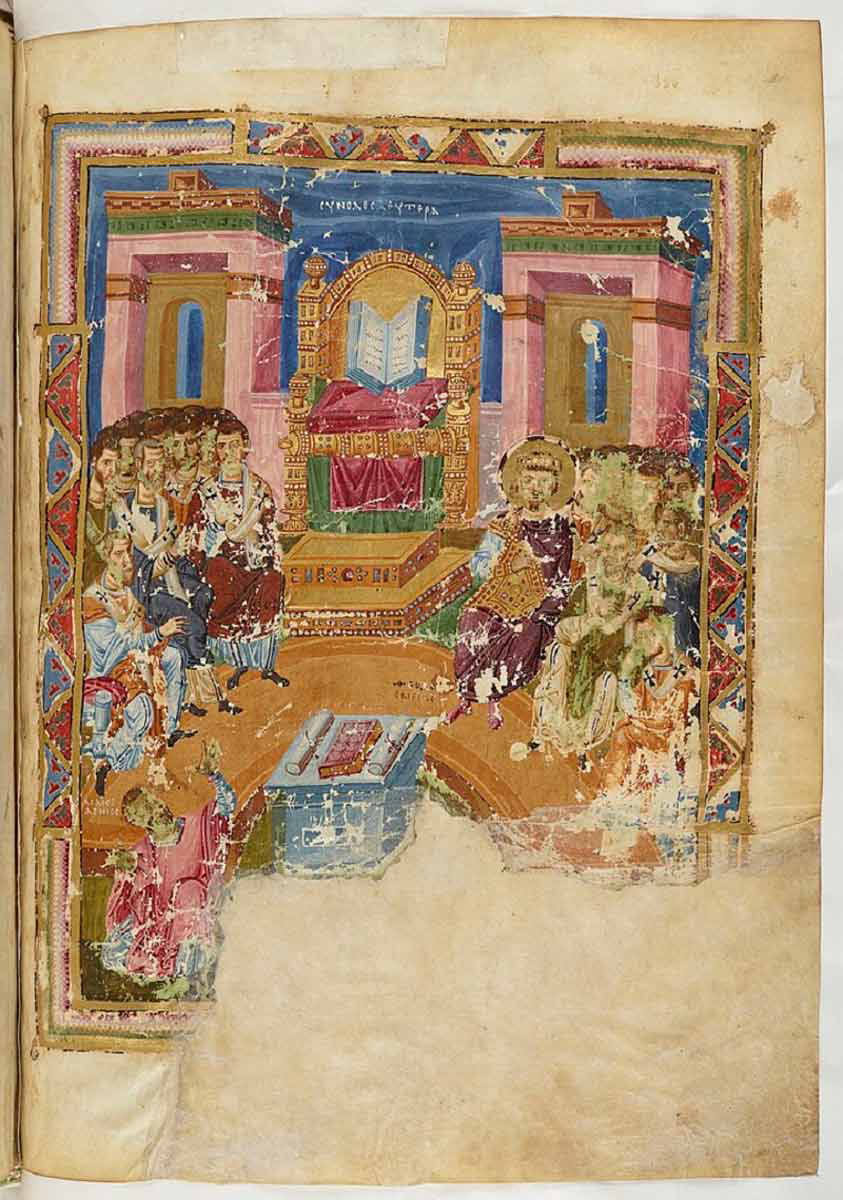

Emperor Constantine IV instructed Emperor Constantine IV to convoke a council in Constantinople to discuss and resolve the issues relating to the wills and natures of Christ and some other matters. The council, which had its first session in September 680, had 18 sessions and the emperor presided over the first eleven. The council adopted the views of Pope Agatho who evaluated the Monothelitist arguments before the council in a synod in Rome which 125 Italian bishops attended. The Sixth Ecumenical Council condemned Monothelitism by adopting the profession of faith Pope Agatho presented.

The council affirmed that Christ had both a divine will and a human will, a doctrine called Dyothelitism. Of the attendees, 174 fathers signed the acts of the council. When the emperor also signed it, the document was sent to Pope Leo II, who succeeded Pope Agatho, and he approved it and had it translated into Latin for Western bishops to sign.

As with previous councils, other matters were also debated, but none as significant for Christianity as Monothelitism vs Dyothelitism.

5. Council of Constance (1414-1418 CE)

Multiple people claimed to be the legitimate Pope from the late 1300s onward. The Council of Constance was called to address the schism in the Church, and it sought to restore unity within Catholicism. The council was convened by Pope John XXII (not to be confused with Pope John XXIII of Vatican II who will be briefly discussed shortly) with the support of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund. An estimated 500 to 700 bishops attended the council held in Constance which is on the border of Germany and Switzerland today.

At the time, much of Italy and parts of Europe recognized Pope Gregory XII as the Roman Pope, while parts of France, Spain, Scotland, and some other regions recognized Antipope Benedict XIII, based in Avignon. To add insult to injury, the Council of Pisa, held in 1409, recognized Antipope John XXIII as the legitimate Papal head. The problem of multiple Popes was resolved by deposing the Papal rivals and electing Pope Martin V as the new and only legitimate Pope. This act restored the legitimacy and authority of the Papacy.

What makes this council relevant to greater Christianity is the trial and execution of the Czech Reformer, Jan Hus. Hus, who was influenced by the teachings of John Wycliffe, criticized the Catholic Church for some of their practices. They ordered John Wycliffe’s bones be exhumed and burned, finding his writings heretical. Hus was executed on July 6, 1415, for criticism of Church corruption, challenge to Papal authority, advocacy for a reform of the Church based on the Bible, and support of the teachings of John Wycliffe.

Hus was a precursor to the Reformation that would start in full swing a century later with Martin Luther nailing the 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. Luther considered Hus an inspiration and said: “We are all Hussites without knowing it.”

6. Second Vatican Council (1962-1965 CE)

The Second Vatican Council, also called Vatican II, was a landmark council in modern church history; it sought to modernize the Catholic Church’s approach to the contemporary world. The world was changing at a rapid rate and the Catholic Church sought to adapt to the times and remain relevant during a time of civil rights and anti-war protests, the sexual revolution, and rapid developments in technology.

Pope John XXIII convened the council, praying for “a new Pentecost” which would see the Church reinvigorated and modernized. The council considered reforms in liturgy, ecumenism, and relations with other religions, and wanted to emphasize the role of the laity in the church. Pope John XXIII passed away a year into the council and Pope Paul VI who succeeded him, concluded the proceedings a couple of years later.

More than 2,000 bishops attended the council alongside leaders of major religious orders and laity which included 20 women. In addition, Orthodox and Protestant observers were allowed to attend.

Changes to the church liturgy, such as presenting Mass in the local vernacular and having priests face the people while delivering the Eucharist, were introduced. The council encouraged dialogue with other Christian denominations and religions. It also promoted the use of technology to engage with the world.

Far removed from earlier Catholic tradition, Vatican II promoted the reading of the scriptures by all members, lay, and leaders in the Church. Lay people were included in the liturgy of the Church through reading scripture passages or assisting with the communion and preparing and leading prayers of the faithful.