It took the early Christian community several centuries to settle which books met the criteria for inclusion in the New Testament. Some books had wide approval, while scholars debated others for almost 300 years before reaching a consensus. The first complete list of books of the New Testament canon appeared in the Festal Letter 39 by Athanasius of Alexandria in 367 CE. Even then, it was not the official canon. Canonization was a long process with several councils considering the matter and settling on the 27 books the Protestant Bible contains today.

The Origins of New Testament Writings

According to tradition, most New Testament texts originated in the 1st century CE. Some books, like 2 Peter, date to the early 2nd century. It was a time of significant expansion and persecution for Christianity. Christian writings, though not all canonical, primarily fell into one of four categories: gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Mary, Thomas etc.), histories (Acts, the Acts of Paul, Acts of Peter, Acts of John, etc.), letters (Pauline Epistles, the general epistles, the Epistle of Barnabas etc.), and apocalyptic writings (Revelation, the Apocalypse of Peter, the Apocalypse of Paul, etc).

Some of these books were pseudepigrapha, meaning the authors falsely attributed them to the person they named the books after, likely to give them credibility. Some of these texts detailed events that followers of the apostles knew to be untrue. They also contained theology that contradicted the core claims of Christianity. Some books were easily identifiable as false, but some faith communities or regions accepted certain books that others considered dubious.

Due to the persecution of Christians during the early centuries of the Christian era, books could not be freely distributed among Christian communities, which limited exposure to some works. When Constantine legalized Christianity with the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, Christians could exchange and study books more freely.

Where local leaders previously determined the legitimacy of books for use in their communities, a broader discussion could now guide Christians to a consensus on the Biblical canon. It set the stage for determining which books were authentic and which were dubious in origin.

Criteria for Inclusion

The need for an authoritative, standardized set of books to serve as a foundation for faith and practice became clear as Christianity spread. Different Church Fathers used varying sets of books they deemed authoritative, and the first order of business was developing the criteria that the books had to meet to be considered canonical. In the 2nd century, scholars set the yardsticks of apostolicity, orthodoxy, and widespread use.

Apostolicity

Apostolicity refers to the connection a book has to an apostle. It did not necessarily have to be authored by an apostle, but the author had to be at least closely associated with one. Of the four gospels, the early Church attributed the gospels of Matthew and John directly to those apostles, while Mark was a close associate of Peter, and Luke of Paul, which allowed their inclusion in the canon. Other gospels, like the Gospel of Mary, were excluded.

Contemporary scholarship often disagrees with the views on authorship that the early Church held on many New Testament books and contributes to our understanding of the New Testament canon. The canon, however, was set long before higher criticism used new methods to analyze the sources.

Because of the uncertain authorship, which is not clearly stated in Hebrews but is in other Pauline letters, the Book of Hebrews took much longer to gain support for inclusion in the New Testament canon.

Orthodoxy

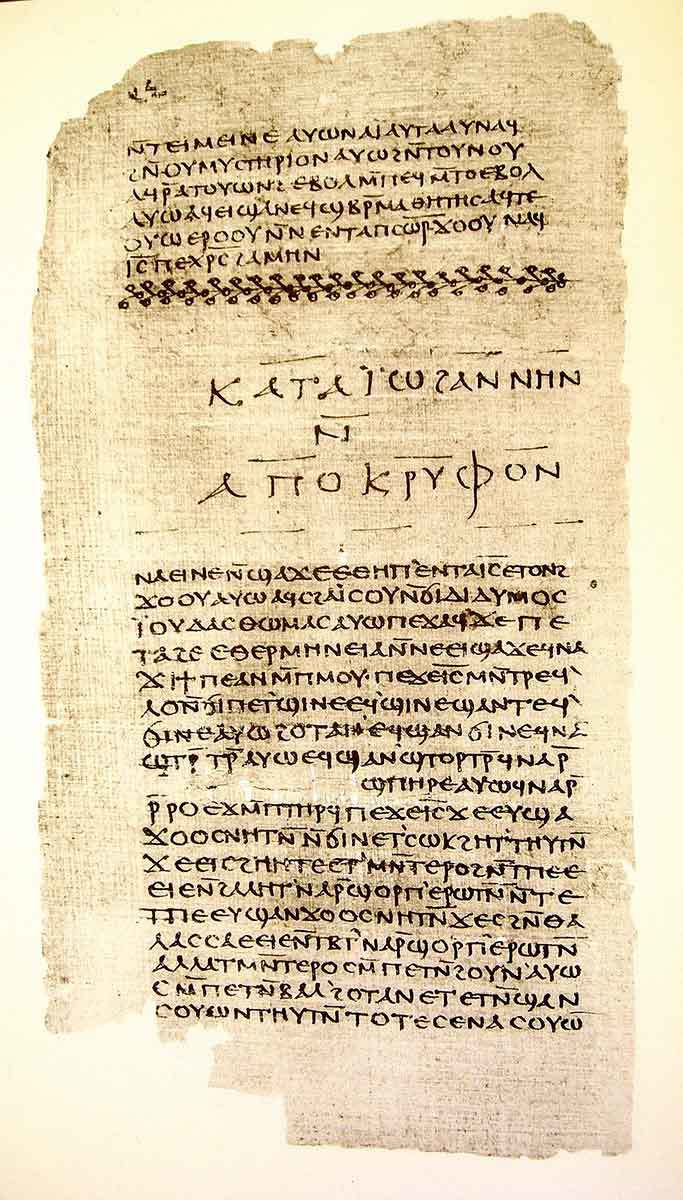

A second criterion for books to meet was orthodoxy, which means the content had to meet the emerging rules of faith in what they taught about God, Jesus, and salvation, among other doctrines. Several early Christian writings promoted the idea of esoteric knowledge. Christian scholars rejected these Gnostic texts offhand.

The Gospel of Thomas, which has received much attention in recent decades and is erroneously described as a “newly discovered gospel,” was well-known to the early Church, but was excluded from the canon partly because of the gnostic teachings it promoted. In contrast, the gospels, Acts, and the Pauline letters received early support for their sound doctrine.

Widespread use

The third criterion for inclusion of a book into the New Testament canon was widespread use. Christian communities shared their religious texts, but some texts would gain traction only in certain regions while others would not endorse them. One example is the Shepherd of Hermas, which scholars in Rome, Alexandria, and the Western Church held in high regard. North Africa and the Eastern Churches, such as those in Antioch and Asia Minor, rejected it. Eusebius of Caesarea, for instance, called it “spurious” in his Ecclesiastical History. The letters by Paul, in contrast, received wide acceptance across all Christian communities of antiquity.

Leaders did not apply these criteria uniformly or instantaneously. Debates about some books raged for centuries before leaders reached consensus on their inclusion in the New Testament canon.

Disputes

Certain books, like Hebrews and Revelation, received much attention, and opposing views had to be thrashed out over centuries before they gained acceptance. The issues differed for the disputed books, with scholars considering one or more criteria doubtful, preventing easy approval.

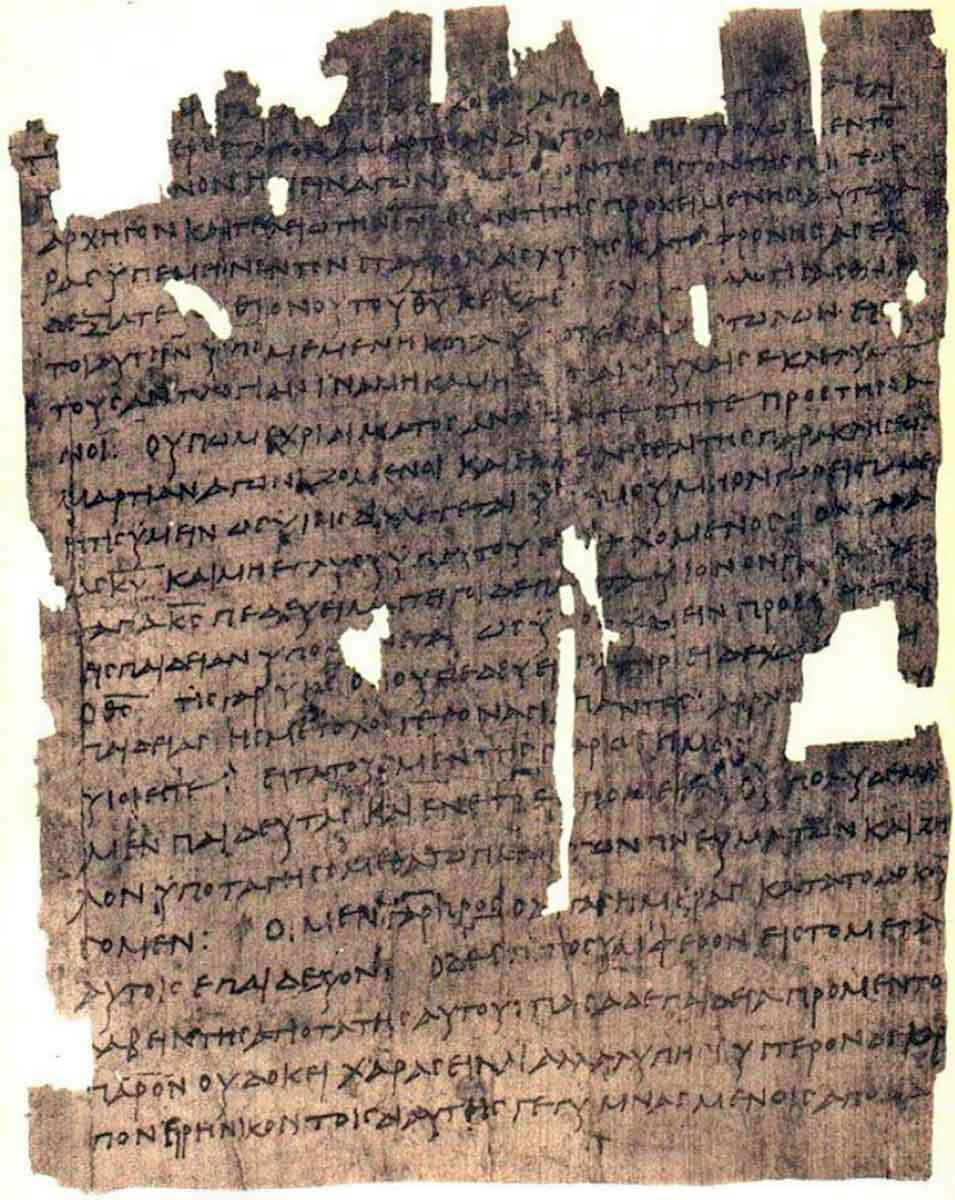

In the case of Hebrews, the authorship was problematic. It was not clear whether Paul authored the book or not, and therefore, the apostolic connection was doubtful. Unlike all the Pauline letters, the author of Hebrews does not identify himself in the opening lines of the letter. The Eastern Church accepted the book as Pauline. North Africa and Rome in the Western Church opposed that view, highlighting the differences in style and vocabulary. These discrepancies could be accounted for if an amanuensis wrote on behalf of Paul. Eventually, scholars included the book due to its theological depth, spiritual authority, and harmony with apostolic doctrine.

Revelation was another hotly disputed book. Its vivid imagery and doubtful authorship raised concerns. Though the book claims John as the author, it is unclear whether it was the apostle John or another. The Eastern Church did not readily accept its authenticity and initially opposed its inclusion because the apostolic connection was doubtful. The style, language, and theology did not seem to align with that of the Gospel of John. Revelation was also not widely used in early Christianity, especially in the East. The symbolic nature of the book raised concerns about dubious interpretations that could result in false doctrine.

Eventually, its claim of apostolic authorship, use by prominent Church Fathers like Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and Tertullian, and its inclusion in lists like that of the Festal Letter by Athanasius and North African Councils, resulted in its inclusion in the New Testament canon.

The Book of James was another contentious book, eventually accepted as canon. The dispute about James was primarily due to his sparse mention of Jesus and his teaching on the relation between faith and works, which some incorrectly interpreted as opposing the doctrine of salvation by faith alone (sola fide), without works. Even Martin Luther contemplated excluding James from his translation of the Bible. He famously called it an “epistle of straw” in his 1522 preface to the New Testament. The passage of contention in James was James 2:14-26, with the famous phrase “faith apart from works is dead” in verse 26. Luther included James in his German Bible and later acknowledged its value for Christian ethics, though he prioritized the epistles by Paul for their focus on justification by faith.

The Role of Church Councils

After the Festal Letter by Athanasius, written in 367 CE, the Councils of Hippo (393 AD) and Carthage (397 & 419 AD) supported the list of 27 books Athanasius first listed. These councils, however, were regional councils and did not settle the matter throughout Christianity.

Claims that the Council of Nicaea (325 CE) established the canon are erroneous and stem from fabrications and misconceptions that arose after the discovery of Synodicon Vetus in the 9th century. It promoted the idea that leaders placed all the books in contention to become the Bible canon on an altar in the church. They prayed that “the inspired works be found on top and the spurious on the bottom.”

Though the 27 books identified by Athanasius and the North African councils helped bolster the authority of those books, some Eastern Churches, like the Syriac Church, continued to use a different, smaller canon for centuries. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church, however, used a broader canon.

While much of Christianity had already accepted the canon of the New Testament since the Councils of Hippo and Carthage, the Catholic Church reaffirmed it at the Council of Trent (1545-1563). On April 8, 1546, during its fourth session, the Council of Trent issued a decree that explicitly listed the canonical books of the Old and New Testaments. For the New Testament, it reaffirmed the 27 books accepted since the 4th century. It correlates with the 27 books in the Protestant Bible.