Nietzsche claimed that his most important work was Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Here, the titular character triumphs over a monstrous creature in a life-or-death battle, and in doing so, he discovers the secret of the eternal return. The concept of eternal recurrence is fundamental to Nietzsche’s philosophy. When Zarathustra triumphs, he credits his victory to ‘sounding brass.’ In a short section of the text, he mentions this idea three times. However, no one in secondary literature seems very sure what it is.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra

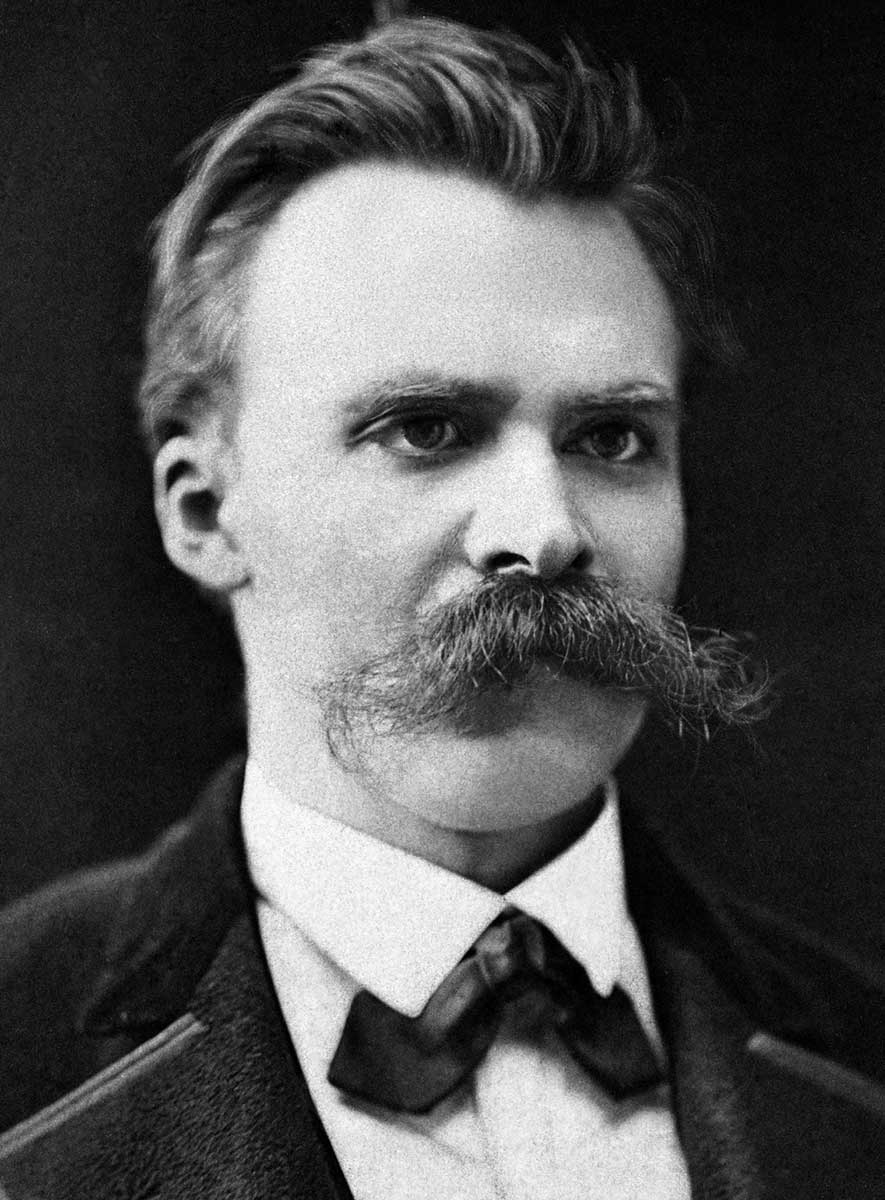

Of all the texts produced by Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), the most important to him was Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Written between 1883 and 1885, it is a poetical work published in four volumes. The book sold poorly. Of the thousand copies initially printed, fewer than eighty were sold in the first year. He fared slightly better the following year, managing to sell just under ninety copies. The third volume barely managed to sell sixty copies. Nietzsche was concerned that his publisher was to blame for poor sales. He felt that Zarathustra was not properly promoted or marketed. But he also knew that the book was a very difficult work. It is written almost entirely in highly symbolic imagery in a language similar to that found in the books of the Old Testament. What is more, Nietzsche wrote each volume in just a matter of days.

Perhaps, for many readers, Zarathustra would be impossible to understand. His friend Dr Heinrich von Stein (1857-1887), a philosopher and tutor to Wagner’s son, once commented that he did not understand a single word of Zarathustra. Nietzsche replied that to have comprehended just six sentences would have raised von Stein up to a level of existence higher than that which most men are capable of reaching.

Today, of course, Nietzsche’s text is considered one of the great poetic works of philosophy. However, despite this acclaim, the work remains a tremendously difficult read. Nietzsche knew this to be the case and claimed that all his subsequent works were intended to help readers understand the ideas behind Zarathustra. The fact that Nietzsche would dedicate the rest of his productive writing life working on texts focused on this work shows just how important Zarathustra was to him.

Here, we will not try to comprehend the entire text but just one phrase and idea from the third book: “in every attack there is sounding brass.”

Zarathustra on the Attack

In Book III of Zarathustra, in a section called “On the Vision and the Riddle,” Zarathustra tells the story of a bizarre encounter he experienced on a mountain. As he attempts to traverse the mountain, a monstrous creature, described as a half-dwarf, half-mole, leaps onto his shoulders. The creature then whispers demoralizing words into Zarathustra’s ears. Zarathustra refers to his attacker as “the spirit of heaviness.” He reveals his own state of mind at the time by referring to himself as “the loneliest one.”

Zarathustra is experiencing a dark moment, perhaps even contemplating his own death. From the rest of the text and by using Nietzsche’s other texts, we know that the creature is saying that life is not worth the effort of living and that Zarathustra’s struggle to live is pointless. These morbid thoughts are the “spirit of heaviness” that weighs him down. Zarathustra tells us that he realizes he must battle the creature and that only one of them can prevail. In other words, if he does not overcome the spirit of heaviness and allows these ideas to take hold of him, Zarathustra will die.

Summoning all his courage and strength, Zarathustra manages to throw the creature off his shoulders. His response to the creature’s assertion that life is worthless and continued living pointless expresses in a single sentence what is arguably the most important idea in all of Nietzsche’s philosophy: “Was that life? Well then! One More Time!”

Here we see a reference to the idea of eternal return. For Nietzsche, how well a person is disposed towards themselves and to life itself can be measured by how happy they would be to live their life over and over, in exactly the same way, for all eternity. When Zarathustra says of life that he wants to do it all again, he affirms life. With this affirmation, the creature is defeated.

Sounding Brass

Now that the scene has been set, we can focus on the mysterious line about “sounding brass.” We have seen the importance of the scene in which Zarathustra defeats the creature by affirming life. And we know that this affirmation has something to do with the eternal return. Nietzsche believed that Zarathustra was his masterpiece and most important work. His preceding works led up to his Zarathustra, and all the subsequent works were attempts to make this one clearer. All this being so, it is quite fair to say that what we are talking about is Nietzsche’s most important idea, expressed in his most important work. This means that when we come across a key phrase that appears entirely baffling, we ought to spend some time trying to decipher its meaning.

We have already seen that this phrase refers to “sounding brass.” In fact, in the passage from Zarathustra that we are exploring, the titular character uses it three times. Let us look at these uses before we take a look at the difficulty introduced by translation.

First of all, when Zarathustra finds the courage to attack the creature upon his shoulders, he says: “Courage after all is the best slayer – courage that attacks; for in every attack there is sounding brass.” He then says that “with sounding brass” human beings can “overcome every pain.” Finally, he says of his triumphant cry “Was that life? Well then! One More Time!” and that there is “much sounding brass.”

Clearly, we need to know what “sounding brass” refers to. Some readers may be familiar with St. Paul’s use of the idea in his First Letter to the Corinthians. This is a passage that Nietzsche would have been particularly familiar with. With royalties earned from his writings, he paid for a headstone to decorate his father’s grave. On the stone, he had inscribed a passage from Corinthians. Is this a clue to the meaning of the phrase?

St. Paul and “Sounding Brass”

St. Paul is one of Nietzsche’s favorite targets. As he does with Socrates, Nietzsche pulls no punches when it comes to criticizing St. Paul. Indeed, his text The Antichrist (written 1888, published 1895) is far more anti-Paul than it is against the figure of Christ. When Nietzsche attacks Christianity, it is always Pauline Christianity that he targets. Interestingly, of all the Biblical texts attributed to St. Paul, Nietzsche is only really interested in First Corinthians.

1 Corinthians 13 opens with the line: “Though I speak with the tongue of men and of angels, but have not love, I have become like sounding brass or a clanging cymbal.” What does St. Paul mean by sounding brass and clanging cymbal?

It is important to note that when he uses the word “or,” he is not referring to two different kinds of things. That is, St. Paul is not saying that if he speaks in this way, he becomes either sounding brass or a clanging cymbal. Both these things are supposed to refer to the same thing. A “clanging cymbal” is another way of expressing the same idea intended by “sounding brass.”

There are three reasons why St. Paul uses this imagery. Firstly, the people of Corinth would be very familiar with brass. Throughout the ancient world, Corinth was famed for its brass production. Secondly, the worshipers of Dionysus would beat brass gongs during their bizarre mystical rites. The Corinthians would understand St. Paul as saying that if he speaks without love, what he is saying is incomprehensible. Finally, and in clever wordplay, in the Greek he uses, St. Paul actually refers to the noise made by a single cymbal. Imagine two finger-cymbals being struck together; now try to imagine only one cymbal. It would be like trying to imagine the sound of one hand clapping. In other words, it is an impossibility.

“Sounding brass” in this sense refers to nonsense or something incomprehensible.

What Is Nietzsche Saying?

If Nietzsche is borrowing directly from St. Paul, and using “sounding brass” in this sense, then it is more likely that he intends it to mean incomprehensible rather than nonsense. Let us feed this interpretation into Zarathustra’s lines and see what sense we can make of them.

- In every attack, there is something incomprehensible.

- With something incomprehensible, human beings can overcome any pain.

- There is something incomprehensible fuelling the triumphant cry: “Was that life? Well then! One More Time!”

This might not seem to get us very far on the face of things, but actually, if Nietzsche is correct, then he has made a useful discovery. When something is incomprehensible, we can attempt to comprehend it. Nietzsche has provided us with a target to direct what he considers to be our most important philosophical inquiries. However, his point might actually be that what gives us the strength and courage to know that life is worth living cannot be comprehended. If this is the case, then we ought not even attempt to try. In our loneliest moments, when the heaviest weight bears down upon our shoulders, we need not search for the proof that life is valuable and our struggle is not pointless. We can just accept that we know this to be the case, even if how we know this remains an incomprehensible mystery.

This second interpretation fits well with something Nietzsche wrote in Twilight of the Idols (1889). This text, written after Zarathustra, is a digest of sorts of all of Nietzsche’s key ideas. Here, he says that philosophers who attempt to judge the value of life itself and judge it to be bad are lacking wisdom. We cannot know the value of life because we are part of it. We can only know that it is good, but not why it is good.

Potential Problems for This Interpretation

A potential problem for the interpretation offered here, of “sounding brass” referring to incomprehensibility, is that Nietzsche does not actually use the words “sounding brass” in Zarathustra. He is, of course, writing the text in German. Here he uses “mit klingendem Spiel.” The literal translation of this does not include “brass.” Rather, the closest rendering into English is “sounding play” or “sounding game.”

Mit klingendem Spiel is very tricky to translate into English. It has a connotation with German military marching bands. However, the idea derives from a practice in battle in which defeated armies that nevertheless fought well were allowed to march off the field mit klingendem Spiel. This meant carrying their weapons and playing their military drums and pipes. In English, we call this “with full honors.” Various translators of Nietzsche’s text into English have offered their own attempts to capture the idea, each with a different rendering. We have seen things like “triumphant shout” and “sound of triumph.” But also, “ringing play” and “clashing play.” Here, the translation is supposed to evoke the sounds of swords hitting each other in combat. One translator, probably drawing on the very old use of the phrase referring to battlefield honors, uses “with fife and drum.”

These translations make sense, but they do not take us very far. The idea that every attack has a sound is not a useful concept. And surely, for his most important idea on the affirmation of life, Nietzsche is not referring to losers retreating off the battlefield. Influential Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann gets close to “sounding brass” when he goes with “playing and brass.” Here we see the introduction of brass. Adrian del Caro’s respected translation gives us “sounding brass.”

The advantage of translating mit klingendem Spiel as “sounding brass” is that it actually takes us somewhere, as seen in the section above. The ideas are also completely compatible with Nietzsche’s other writings.