Today, approximately 1.8 million Mapuche, once called Araucanian, live in Chile, making it the country’s largest Indigenous group. Once itinerant hunter-gatherers, Spanish colonization and its aftermath had a profound impact on the Mapuche people. Despite centuries of resistance, which inspired similar movements throughout the hemisphere, they ultimately saw their territory annexed and their way of life upended. Many continue their centuries-long battle for recognition and autonomy today.

Pre-History of the Mapuche

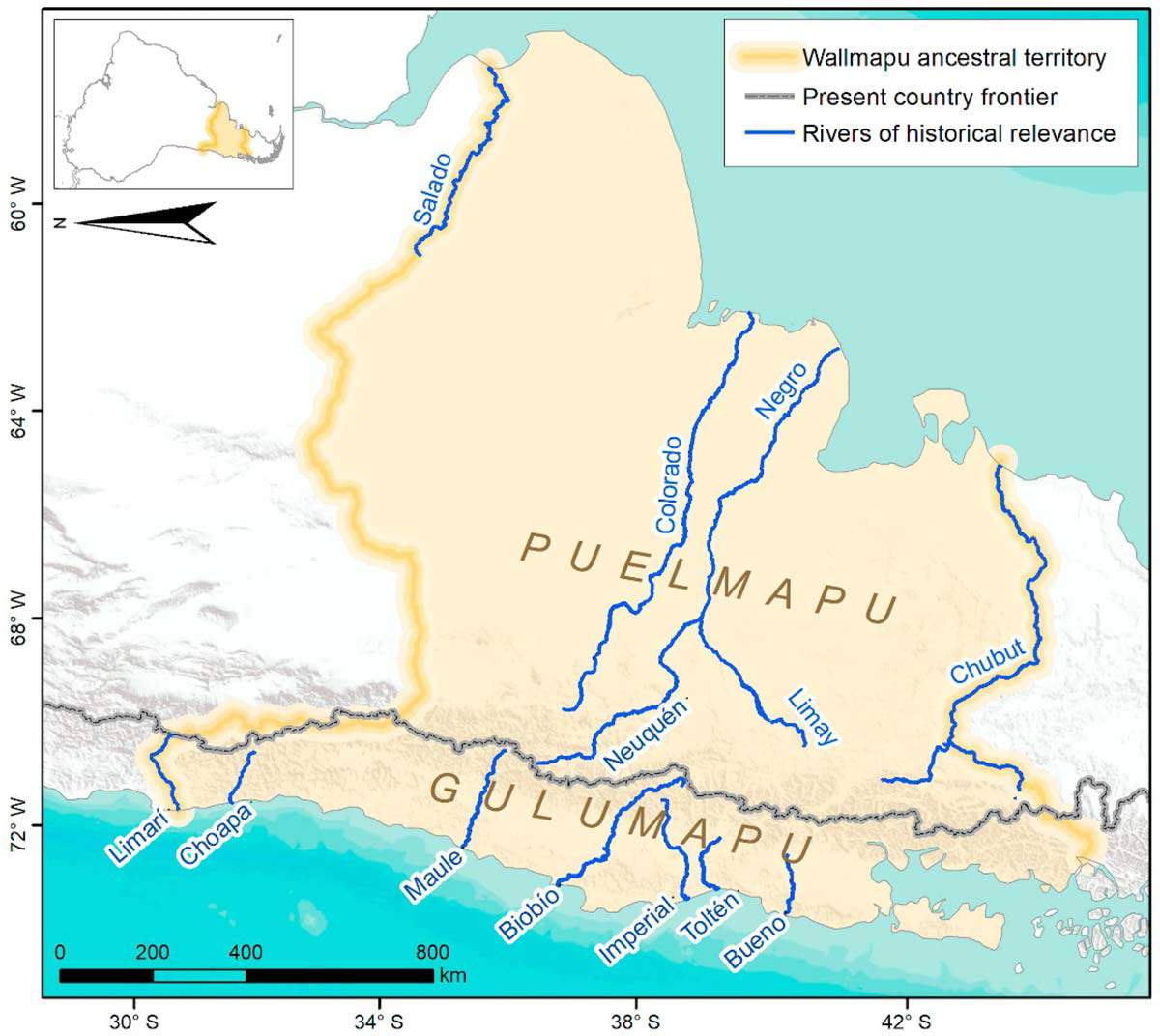

How the Mapuche (“people of the land”) came to occupy present-day Chile is a matter of scholarly debate. The prevailing theory had long been that they originated among hunter-gatherers in present day Argentina before crossing the Andes. Modern analysis suggests it is more likely that Indigenous groups on the eastern side of the Andes actually originated from Mapuche ancestors who once occupied the coast of southern Chile. Whatever the case, definitive proof of early Mapuche culture in central-southern Chile appears around approximately 600-500 BCE.

Mapuche territory, Wallmapu, included what is today central and southern Chile, but may at one time have stretched as far north as Peru and as far east as Buenos Aires. However, some areas were more densely populated than others. The Mapuche “heartland,” stretching from the Itata River to Chiloe Island, may have held nearly 1 million people by the early 16th century. Scholars suggest that by the 15th century, the group’s existence still largely revolved around hunting and gathering, along with small-scale farming.

Scholars have also theorized that prior to the need to defend against “outsiders,” the Mapuche likely lived in smaller, more isolated groups. However, they shared a common language, Mapudungun, and cultural practices, and their lifestyle did not support the formation of a cohesive civilization. Without a written language, much of the group’s pre-history has been lost to time. Furthermore, the humid climate in which the majority of the Mapuche lived did not lend itself to the preservation of artifacts.

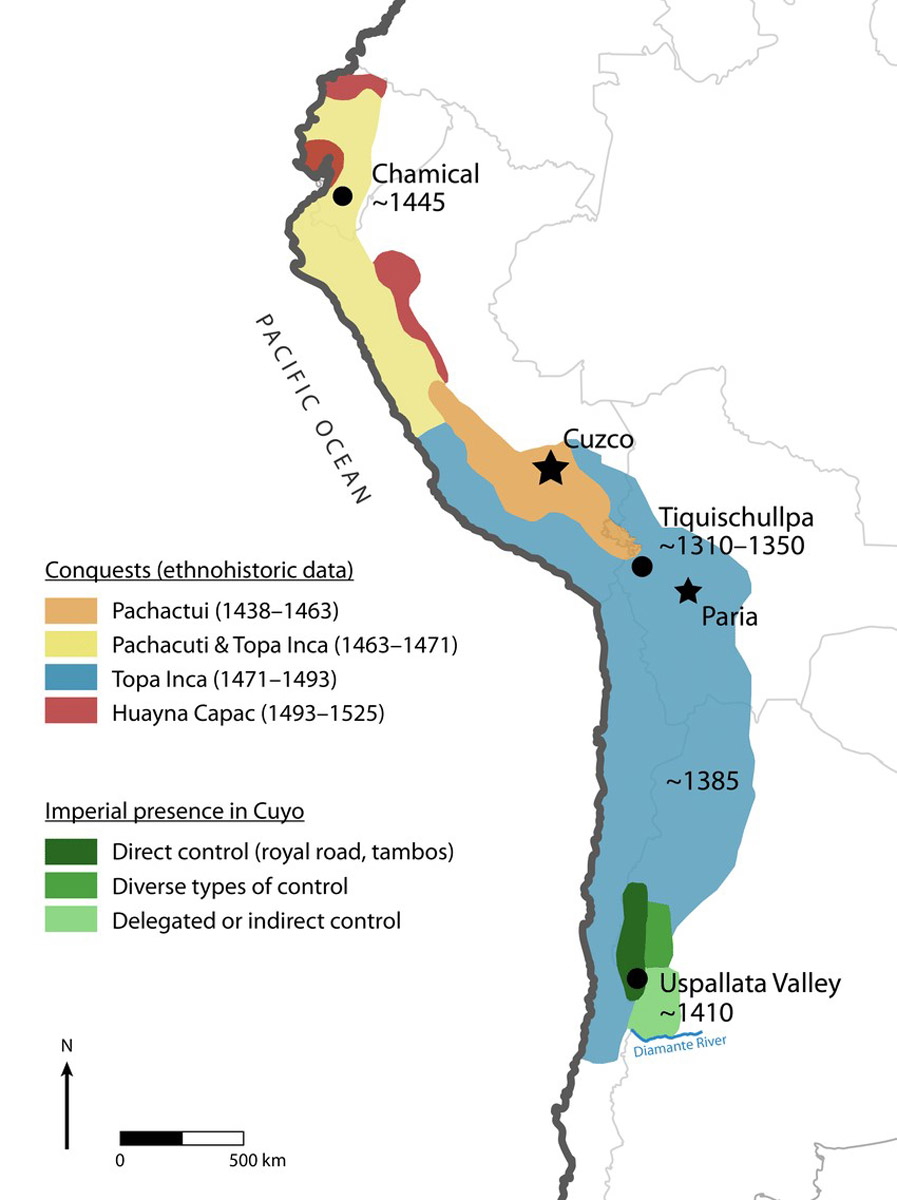

Inca Conquest

Before having to contend with Spanish colonization of the 16th century, the Mapuche people first had to deal with the Inca. During the 15th century, Tupac Yupanqui, father of the last Inca King, Huayna Capac, was set on expanding the Inca Empire and began to push further into present day Chile, conquering the northern part and the Picunche (northern) people. Spanish chronicler Garcilaso de la Vega claimed that once the Inca began pushing into the Mapuche territory, in central Chile, a week-long battle ensued, the Battle of the Maule, after which both sides withdrew, the Inca gaining no advantage and the Mapuche maintaining their territory south of the Maule river valley.

Some historians argue that this Inca-Mapuche encounter occurred much later, during Huayna Capac’s reign, and the attempt to win Mapuche lands was abandoned because it was ultimately determined not to be worthwhile—the structure of Mapuche society, as it were, would not have been able to serve the Inca Empire. The Inca needed some kind of government organization in order to administer their empire and the Mapuche did not have one. However, while the Mapuche were never conquered by the Inca, archaeological finds and evidence of more advanced agricultural practices in Mapuche territory closest to the empire suggest the influence of the Inca on Mapuche culture.

Spanish and Chilean Colonization

Colonizers first encountered the Mapuche in 1537, but had minimal interaction with them for several decades, with their efforts focused elsewhere. When the Spanish did determine to take over Mapuche territory, and their people with it, they met fierce resistance. In 1553, the Mapuche launched a coordinated attack on Spanish forts in their territory, killing the Spanish governor, Pedro de Valdivia, and forcing them to abandon all but one settlement. This was the beginning of over a century of struggle between the Spanish and Mapuche, who were determined to remain independent.

The early success of the Mapuche can be in part attributed to their unintentional spy. At age 11, Lautaro was captured by the Spanish and forced into the service of Valdivia. He remained captive until he was 17, at which point he escaped and returned to his people. His years as a servant gave him unique insight into the Spanish people and their military strategies—which he then used to devise the Mapuche’s methods of resistance. He was one of the principal leaders of the 1553 uprising, having risen to power by sharing his knowledge of Spanish weaknesses and teaching his people Spanish military tactics. He continued to fight against the Spanish until being killed in battle in 1557.

The War of Arauco raged on until a devastating Spanish defeat in 1598. After that, over a period of six years, the Spanish were forced to abandon all of their cities in Mapuche territory south of the Bio-Bio River. This opened the way for intermittent negotiations with the Mapuche. A peace agreement of sorts was reached after the final major Mapuche uprising in 1655, after which the Spanish largely maintained a border with the Mapuche at the Bio-Bio River.

By 1810, Chile had declared independence from Spain, though battles with royalists persisted for several decades. Once Chile had secured said independence and Spanish aggression ended, the process of building a truly independent nation began. So, too, did new troubles for the Mapuche. While they had largely been allowed to maintain their territory in the previous decades, the burgeoning nation now set its sights on the group’s fertile lands, while incursions from new European settlers became more frequent. By the 1860s, a slow military and colonial encroachment into Mapuche territory had begun, a process dubbed “pacification,” though it was rarely peaceful.

The Chilean state gradually pushed its frontier southward, first through either military confrontation or treaties, and ultimately via the eradication or forced assimilation of the Mapuche. Those who remained were moved to reservations occupying just 6% of their ancestral lands, which were slowly annexed over the following centuries, leading to stark poverty and mass migration to urban areas.

Mapuche Culture and the Spanish Influence

At the time of the conquest, the Mapuche lived largely in semi-permanent settlements of extended families or tribes (lof), headed by a patriarch or longko. They worked collectively, hunting, gathering, and farming at a small scale, and equally distributed their resources. Agreements and disputes between lofs were settled at koyagtun, meetings in which leaders discussed trade, war, and similar issues. Men were responsible for hunting and farming while women handled household tasks, childrearing, gardening, and passing down the families’ cultural heritage to new generations.

Though they practiced a number of handicrafts, most notable was weaving, much like their neighbors to the north. The earliest evidence of textile production among the Mapuche has been dated to the 14th century, though the climate they generally resided in was not optimal for preservation. Textiles and the women who made them were highly prized in Mapuche society, and textiles were used as trade goods as well. Using camelid fibers and vertical looms, Mapuche women produced the traditional clothing of their people—dresses, shawls, and belts for women; chiripas (a rectangular garment tucked into a belt and wrapped around the legs like trousers), belts, and ponchos for men.

The traditional Mapuche religion revolved around a number of gods and spirits, as well as a focus on the ongoing relationship between the living and the ancestors. The machi, or shaman, traditionally a woman, was a central figure, acting as the intermediary between the natural and supernatural realms, as well as a healer. The Mapuche developed a number of spiritual ceremonies, including nguillatun, a ceremony of prayer and machitun, a healing ritual, that are still celebrated in some communities today. These ceremonies are marked by the use of a traditional drum, the kultrung, designed specifically for each machi and imbued with their spirit. Particularly in smaller rural communities, machis are still central religious figures today.

While the Mapuche were able to resist Spanish colonization—and de facto enslavement—for over one hundred years, their arrival still had a major impact on the group’s social and political organization, as well as cultural practices. The once-independent tribes had to further organize and cooperate in order to fight their would-be colonizers. This required more permanent settlements, bringing multiple groups together, a more stratified social organization, and a change in their way of life, as they could not invest time in the slow process of hunting and gathering while simultaneously fighting the Spanish.

The Mapuche shifted their focus to raising animals, particularly those introduced by the Spanish, and more intensive farming, while settling in larger groups. They also adopted a more structured political organization to administer these larger groupings (rehues), and selected war chieftains, toqui, to lead ongoing warfare against the invaders. Yet ultimately, the Chilean state won out, and the Mapuche way of life slowly disappeared. Though many cultural practices remained, particularly religious practices, which in many cases were integrated with Christianity, the Mapuche could no longer maintain their traditional lifestyle.

Mapuche in the 21st Century

Today, people of Mapuche descent make up approximately 10% of Chile’s population. It is the largest Indigenous group in the country, numbering nearly 2 million people. Though the Mapuche have integrated into modern society, with the majority living in urban areas, there remains a strong movement to preserve their traditional culture and lifestyle, as well as ensure their rights and maintain their territories. While most groups are not advocating for independence, they are demanding the protection of collective land rights, access to bilingual education, and political representation.