Orthodox Christian art has almost nothing in common with its Catholic and Protestant counterparts despite the shared foundation found in the Holy Scripture. It was initially based on the Byzantine tradition of painting and mosaic-making. Highly stylized, dark, and strict toward its viewer, it was designed to provoke deep repentance and unwavering devotion. Read on to explore the rich history of Orthodox Christian art and its unique, timeless peculiarities.

How Did Orthodox Christian Art Emerge?

Orthodox Christianity emerged as a separate branch in 1054 after the Great Schism, which separated Eastern and Western religious beliefs. The Schism was caused by differences in theological interpretations and worship practices and claims of influence over certain territories. After the Schism, two centers of Christian worship—Rome and Constantinople—and two faiths—Catholic and Orthodox—emerged.

Orthodox Christian art was initially based on the Byzantine tradition of painting and mosaic-making. After the Christianization of the Kyivan Rus in the 9th century, masters from Byzantine came to teach local artists canons of religious painting. Over the years, the styles gradually grew apart, with the development of local styles and the emergence of regional saints. Gradually, the Russian Orthodox Church separated into its own denomination, loosely connected to its colleagues in the Byzantine Empire and, later, Greece. In this text, the notion of the Russian Orthodox Church refers to the branch of Orthodoxy dominant in the territory of Kyivan Rus and other states in the present-day territories of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia.

Today, Orthodox Christianity remains prominent in Eastern and Southeastern Europe, some parts of the Middle East, and even in Ethiopia, where it had spread centuries before the African continent’s colonization.

What Made Orthodox Art So Different?

Orthodox Christian paintings, usually called icons, did not offer innovative approaches to composition, eye-catching details, or excessive emotion. Unlike many Catholic religious artworks, they are strict and sober, with every element refined and stylized. They have only one function—to be revered. These icons do not aim to educate or entertain the churchgoers. The lack of clear storytelling, however, makes Orthodox images even more relevant to the worshipers, as each could adapt the subject to their own pains and needs.

Traditionally, Orthodox icons were painted on wooden boards glued together and smoothed with a piece of thin linen. Proper treatment and drying of the board were necessary to avoid deformation and prolong the icon’s lifespan. However, if the board is not dry enough, it can become even more significant for some followers. Centuries after its creation, wet boards can react to temperature and humidity fluctuations by producing aromatic liquid—crying or bleeding, which, according to some, gives the icon miraculous prophetic or healing properties. Unfortunately, exploring the phenomenon in depth is almost impossible since most churches do not allow research teams access to their objects of worship, as it may be considered sacrilege.

The linen-covered board was then treated with a mixture of chalk, fish glue, and linseed oil to create a base for the tempera paint, a combination of egg and pigment. Tempera dries quickly and retains its brightness for centuries, being less versatile but more durable than oil paint. After a preparatory sketch, the painter would cover the background and decorative elements like halos with thin gold leaf and paint the image. To bind together layers of board, linen, and paint, the icon was then soaked in linseed oil, creating a glossy top layer.

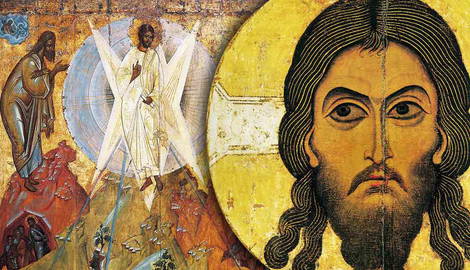

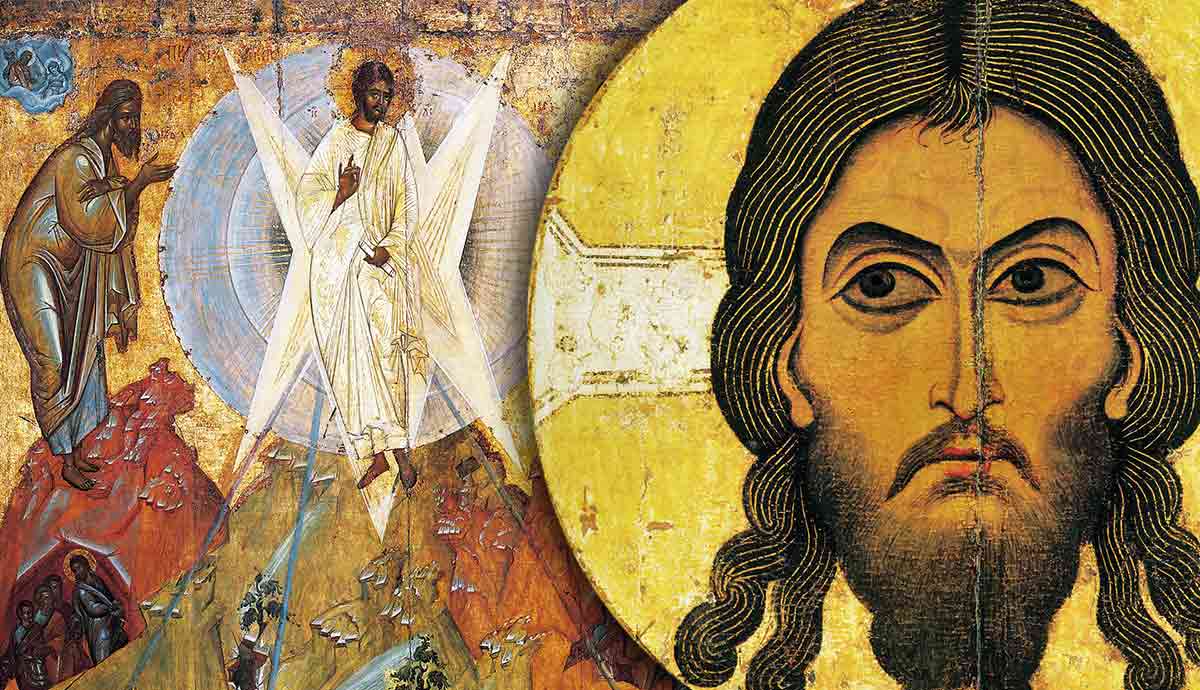

The Orthodox painting canon was and remains strict and binding, disallowing any innovation more serious than a slight variation of color tones. Orthodox icons usually relied on the so-called reversed perspective. In linear perspective, typical for the majority of Western art, perspective lines meet at the horizon, creating the illusion of depth at the center of the canvas. In traditional Orthodox canon, the focal point is located not within the image but right in front of it, in the place reserved for the worshiper. Reversed perspective is often regarded as more natural to the human eye, but in the Orthodox canon, it has another function. It is a clear indication of the hierarchy inside the church: it is not the believer who looks at the saint, but the saint who observes and evaluates the believer’s deeds and thoughts.

What Was Raskol and How Did It Affect Art?

Raskol, meaning schism or split, was a dramatic event that occurred in the 17th century as a result of a rather unpopular religious reform. In the 1650s, Russian patriarch Nikon decided to take a step towards the Greek Orthodox Church for the first time in centuries, adapting Russian rituals to the Greek norms. Among many other reforms, Nikon demanded that the sign of the cross should be made with three fingers rather than with two. Painting canon was also forcibly changed and made even stricter and no-nonsense. In particular, the reform banned painting Saint Christopher, the patron saint of travelers, as a dog-headed man. According to the legend, Christopher came from a man-eating race of Cynocephalus with dog heads and human bodies. Upon meeting baby Jesus, he repented his sins and became a Christian.

Some followers eagerly adopted the reform, while many others, citing centuries-old traditions of worship, refused to comply. The government implemented drastic measures, with forced baptisms, imprisonments, and even executions of those who maintained the old ways. And yet, Raskolniki, or the followers of the pre-reformed cult, kept practicing their faith, turning into an underground religious network, officially accused of heresy by the official reformed Church. They still exist even today, with no prosecution, and usually under the name Old Believers or Starovery.

Around that time, a group of traveling merchants saw an opportunity to expand their business and conquer a new market. Known as afeni, these merchants operated both legally and on the black market, traveling by foot or on small boats. Afeni had their own constructed language that allowed them to share information within their developed networks without attracting the authorities’ attention. Even before the schism, they often sold religious art and icons, competing with more official painters from monasteries. After Raskolniki were proclaimed heretics, a new market opened to the merchants, who then could supply them with icons and religious objects made by old canons with no competition. This black market helped preserve the pre-reformed Orthodox art.

Who Were the Most Famous Painters in Orthodox Christianity?

Just like with Western Medieval artists, we will never know the names of many prominent painters of the Orthodox church. Before modernity, the identity of an author was irrelevant to their contemporaries and thus rarely mentioned. However, some artists were so outstanding that their names remained in archival records and documents from the era.

To Orthodox Christians, the concept of The Holy Trinity is one of the central theological dogmas. According to it, God is a unity that nonetheless reveals himself in three persons, representing The Father, The Son, and The Holy Spirit. The Trinity is similarly present in any living human, embodying the unity of their mind, flesh, and spirit. The most famous work of Orthodox Christian art, The Trinity by Andrei Rublev, painted in the 15th century, became almost synonymous with this concept. Rublev’s biography mostly remains a mystery, but his name was popularized not in the least because of the iconic 1966 film by Andrei Tarkovsky, shot in black and white. In 1988, Rublev was declared the patron saint of artists and other art-related professionals.

Another important figure was Theophanes, The Greek, also known as Feofan Grek. Theophanes, a contemporary of Andrei Rublev, came to the Novgorod Republic from Byzantine, where he believed his artistic expression was not appreciated. In Novgorod, Theophanes created almost monochrome images of saints that decorated local churches and manuscripts. Despite following the strict canon, the artist was known for his unusually realistic and lively faces.

How Did Orthodox Christian Art Affect Modernism?

Orthodox Christian art continued to live and develop even in the modern era, with some of the famous secular painters invited to create religious images. One of those artists was Mikhail Vrubel, a Russian-born artist who was invited to paint the interior of Saint Cyril’s church in Kyiv. Popularly known as a symbolist, Vrubel was an artist who was confined to his own mind and not connected to any formal movement. His mosaic-like style of painting and grotesque faces unsettled and fascinated. For the church, he painted an image of the Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus in her arms. In Mary’s huge eyes, one could read the pain and sorrow of knowing her son’s future. The fresco caused a stir, but not due to Vrubel’s innovative stylistic choices. Vrubel’s mentor, art historian Adrian Prakhov, recognized his wife in the painted features, with whom Vrubel was desperately in love.

After centuries of existence, Orthodox icons became something too familiar to artists, with fashionable Western movements overpowering traditional influences. The radical turn happened when a group of young radicals started to look for alternative sources of inspiration. At the beginning of the 20th century, art conservators of the Russian Empire and, later, the Soviet Union embarked on a large-scale project of restoring old Orthodox icons. After cleaning the darkened layers of lacquer and soot from ritual candles, they saw vibrant and dramatic images made of bold colors and refined brushwork. The generation of Russian and Ukrainian avant-garde artists, including Kazimir Malevich and Natalia Goncharova, adopted the aesthetic and philosophical principles of Orthodox Christian icons for their works.