Orthodox Christianity and the art inextricably linked to it can be traced back to the early Christian belief systems, but most recognizably to the graphic, stylized art of Byzantium. With its roots in the Greek word eikon, meaning image, Orthodox icons have always been a strictly controlled and restrained art form. Artists practice their craft, focusing their personal devotion to God, whilst ensuring that the icons are emotionally conservative in style. Although the icons can be seen as decorative pieces, their primary function remains as an object of focus for reverence and prayer.

The Origins of Orthodox Iconography: Iconoclasm and Beyond

The development and reinvention of Orthodox Christianity over the centuries began with the establishment of the Eastern Orthodox Church, said to date back to Christ and his Apostles. From the 3RD to the 8th centuries CE, the liturgies and general tenets of the Church were established. Missionaries disseminated their beliefs throughout Eastern Europe, reaching Russia, Serbia, Romania, and beyond before the Great Schism of 1054 divided the Eastern Orthodox and the Latin Church (later becoming the Roman Catholic Church). Despite such a cataclysmic change in the religious world, Orthodoxy flourished, and alongside it, iconography came to provide the word of the Gospels in image form.

The Rules

The Second Council of Nicaea in 787, a key moment in the history of Orthodox art, held that an icon is the visual equivalent of the Gospels, a counterpart to the written word. The Council argued that, as looking upon an icon was, in effect, looking upon God himself, it could not be considered iconoclastic. This vital decree was elemental to the exponential flourishing of iconography throughout the Orthodox Christian world.

Far from the freedom of spirit and creative expression typically associated with art, Orthodox iconography adheres to strict rules, including prayers related to its production. A prayer is offered by the iconographer before beginning the work of painting, in addition to prayers during the icon’s creation, and following its completion. An iconographer is not your average artist. Blessed by a priest before embarking on his career of devotional art, the iconographer holds an important position in the world of the Orthodox church.

Concerning subject matter, images of Jesus, the Virgin and Child, or a particular saint or group of saints relevant to the intended destination of the icon dominate. While icons may seem unemotional and stiff to the untrained eye, they are not intended to be a realistic portrayal of a person, but a visual focus for contemplation. The artist’s goal is that an icon provides a window into heaven, a phrase synonymous with the concept of the icon.

The Style of Stylization

When we think of an Orthodox Christian icon, it is often the Byzantine-influenced Greek or Russian images with their highly stylized, static appearance and the generous use of gold that come to mind. A good example is the one shown above, Saint Anne with the Virgin. There is no attempt at realism here. What is important is that the painting displays the necessary traditional elements to enable worship. The two saints appear with no explanatory background, showing their location, nothing to root them in an earthly context.

Even the form of perspective—reversed perspective—used by authors, differs from what we have become accustomed to in linear perspective. In the Medieval period, the use of linear perspective was developed to create the impression of depth in a painted image. Iconographers used the reverse of this to focus the viewer’s attention and prayer on the saint portrayed. Rather than the viewer observing the image as in traditional art, with icons, the saint regards the devotee, as though to remind them that they are both divine images and creations of God.

Earthly Materials for Divine Worship

The majority of small, portable icons intended for personal devotion are made from natural materials, adding an extra layer of symbolism to their creation. Traditionally, a wood panel support is coated with a piece of linen, and a primer layer, usually a mix of fish glue, chalk, and oil, is added.

Pigments such as cinnabar and lapis lazuli, along with gold leaf or, in earlier centuries, hammered gold, form the basis of the image. The pigments, mixed with egg yolk, combine to create one of the oldest and most durable forms of paint in art history, egg tempera.

In temples or churches, however, Orthodox iconography is often on a monumental scale, and that is where mosaic comes in. A wonderful example of iconography at its peak is the decoration within the 1500-year-old Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. The first iconographic mosaics were destroyed under Muslim influence as a period of iconoclasm stemming from the prohibition of the worship of idols and icons during one of the edifice’s incarnations as a mosque.

In 843 CE, the Triumph of Orthodoxy came about following the death of Emperor Theophilus, the last supporter of iconoclasm. The following period saw a resurgence in the creation of mosaics in the form of icons. Despite this, at various periods in the Hagia Sophia’s long history, the mosaics have been whitewashed and plastered over, most notably following Mehmed II’s conquest of Constantinople in 1453. In 1935, work to uncover these important devotional works was completed, and the Hagia Sophia was opened, in all its glory, to the public. In recent years, following a turbulent history, it returned to service as a mosque.

In addition to the natural materials used, colors have important and specific meanings in iconography. The colors that dominate the iconographer’s palette are the following:

- Gold, extensively used in all forms of Orthodox iconography, represents the divine light of God and the eternal daylight of Heaven.

- Blue symbolizes the infinity of the skies as well as the heavenly nature of the Virgin, hence its use for her robes.

- By contrast, red is used to depict earthly matters, but more importantly in Orthodox Christianity, the blood of Christ and of his sacrifice.

- White denotes purity and innocence.

Symbolism

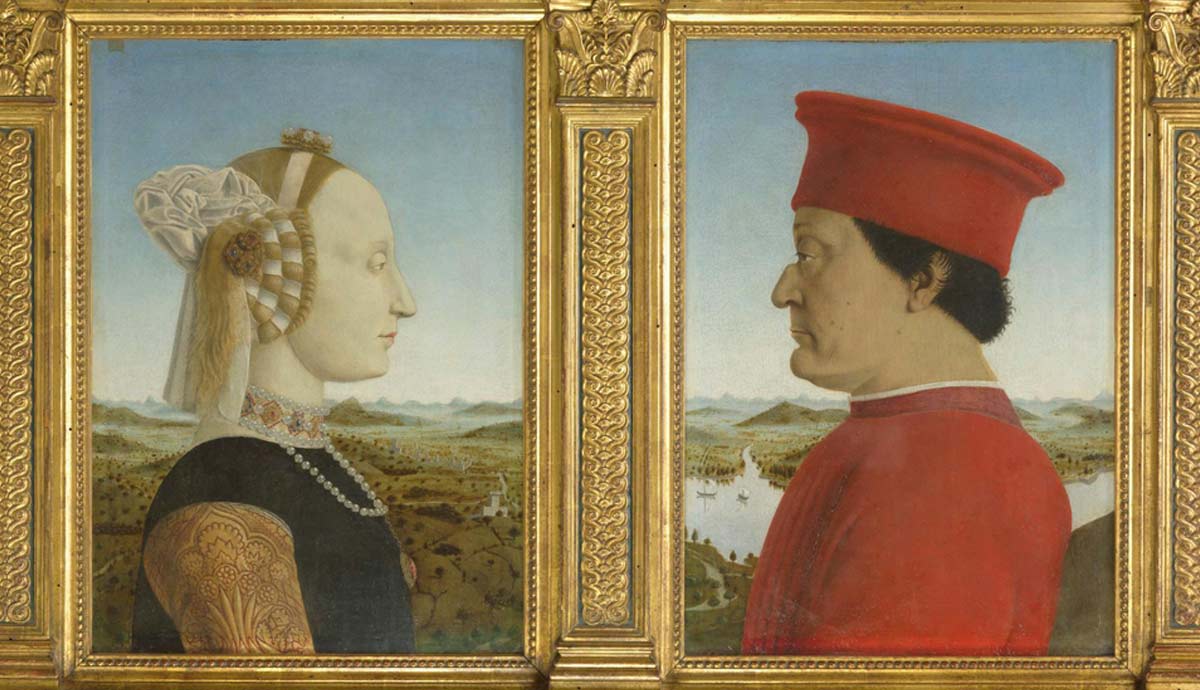

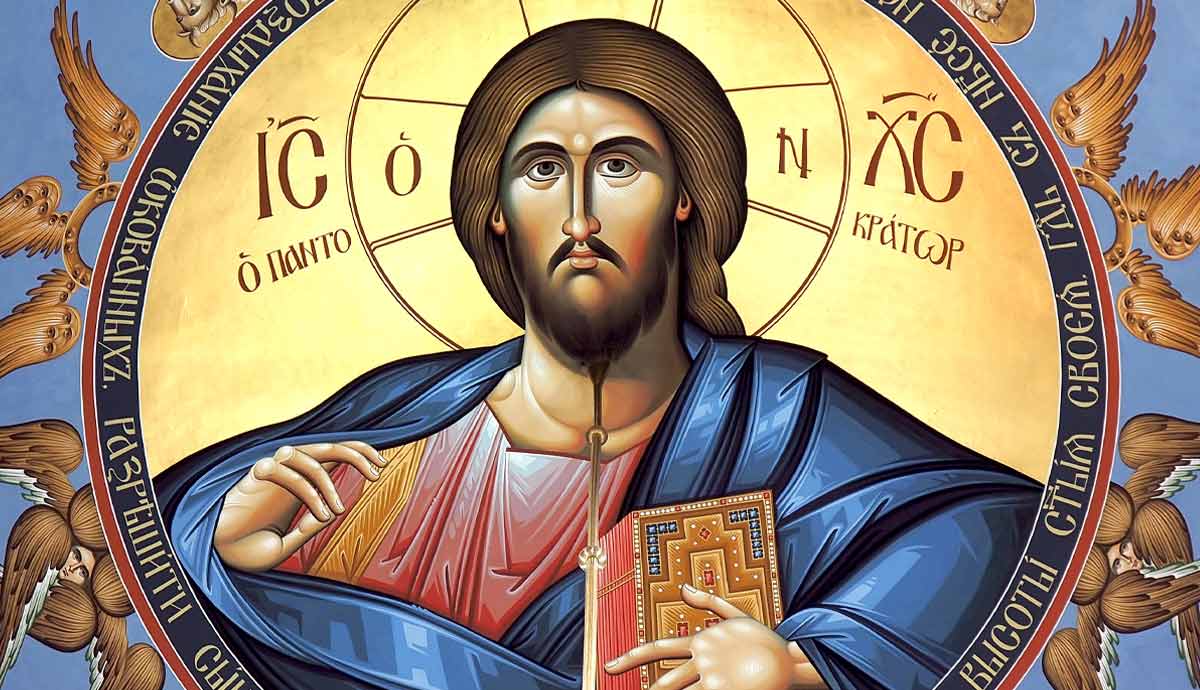

Iconography has little in common, beyond the materials used, with painting or image creation, as we think of it today. The icon operates in a different sphere from the Renaissance portrait, for example. Whereas, in 15th-century Italy, a wealthy banker might commission a portrait showing such symbols of his influence and power as his Florentine palace in the background, an Orthodox icon of Christ Pantocrator would portray, quite simply, Christ alone as a devotional entity. As a work filled with symbolism, Christ Pantocrator, or ruler of all, dominates the world of icons. From the proscribed hand positioning to the letters included in Christ’s halo, every element conveys a meaning.

The letters in Christ’s halo in many versions of the Pantocrator refer to the name of God revealed to Moses in the burning bush and mean I am that I am. The inscription IC XC, or sometimes IC XC Nika, in Greek, gives us the first and last letters of Jesus Christ, or Jesus Christ Conquers. Christ’s hand in the icon above is positioned in one of the proscribed gestures in iconography—the blessing hand. The letters IC XC are formed by the fingers, reflecting the lettering above Christ in the image.

The symbolism of color is reiterated here. Christ wears a blue robe, signifying his heavenly origins, with a red robe beneath it. The red symbolizes his earthly appearance as a man, as well as his Passion, and thus the combination of the two, along with the Godly gold leaf, indicates the sublime divinity of Jesus Christ.

| How to Read a Christ Pantocrator Icon | |

| Halo letters | allude to the Divine Name at the burning bush — “I am that I am.” |

| Inscription | IC XC / IC XC Nika = Jesus Christ / “Jesus Christ Conquers.” |

| Hand gesture | blessing hand; fingers form “IC XC,”

mirroring the inscription. |

| Colors |

|

Orthodox Iconography in the 21st Century Is Still Relevant

Although the history of Orthodox iconography is long and tumultuous, this singular form of divine veneration continues to thrive in the 21st century. Following the strict guidelines and approaches cemented over centuries, iconographers perpetuate the tradition of producing icons for worship and contemplation. A search on the internet will reveal any number of companies and individual iconographers offering their services to those wishing to commission a personal icon. Whilst different forms and materials have been utilised over the history of Orthodox iconography, it appears that modern iconographers and worshipers favor the traditional red, blue, and gold of the Byzantine-influenced egg tempera images.

Perhaps the simplicity of the colors and forms of antiquity offers a powerful link to the origins of the Orthodox church. This purity may serve to add focus to prayer, eliminating, as it does, any extraneous detail that might detract from its purpose. Our examination of the symbols and meanings behind Orthodox iconography reveals that icons are far more than just art. They are considered to be windows into heaven, the image of God providing an almost tangible connection with the viewer, and their importance and relevance look set to continue for centuries to come.