In 508 BCE, Athens began to experiment with a political system that was unheard of in the ancient world: democracy. The people of Athens, tired of the cycle of political violence and aristocratic power grabs, overthrew their tyrants and seized power for themselves. Under the leadership of Cleisthenes, Athens reformed its constitution and transferred political power into the hands of the demos, the people. One of these powers was ostracism, the authority to exile any citizen from the city for ten years.

What Is Ostracism?

Ostracism was a procedure by which the people of Athens could democratically elect to exile one of their citizens for a period of ten years. The process was developed as a way to defend against tyranny. Should any one man gain too much power, the people could exercise their right to have that man expelled from the city. The exiled person’s property remained theirs, and they maintained their citizen status. When their exile ended, they were allowed to rejoin the city with their reputation intact.

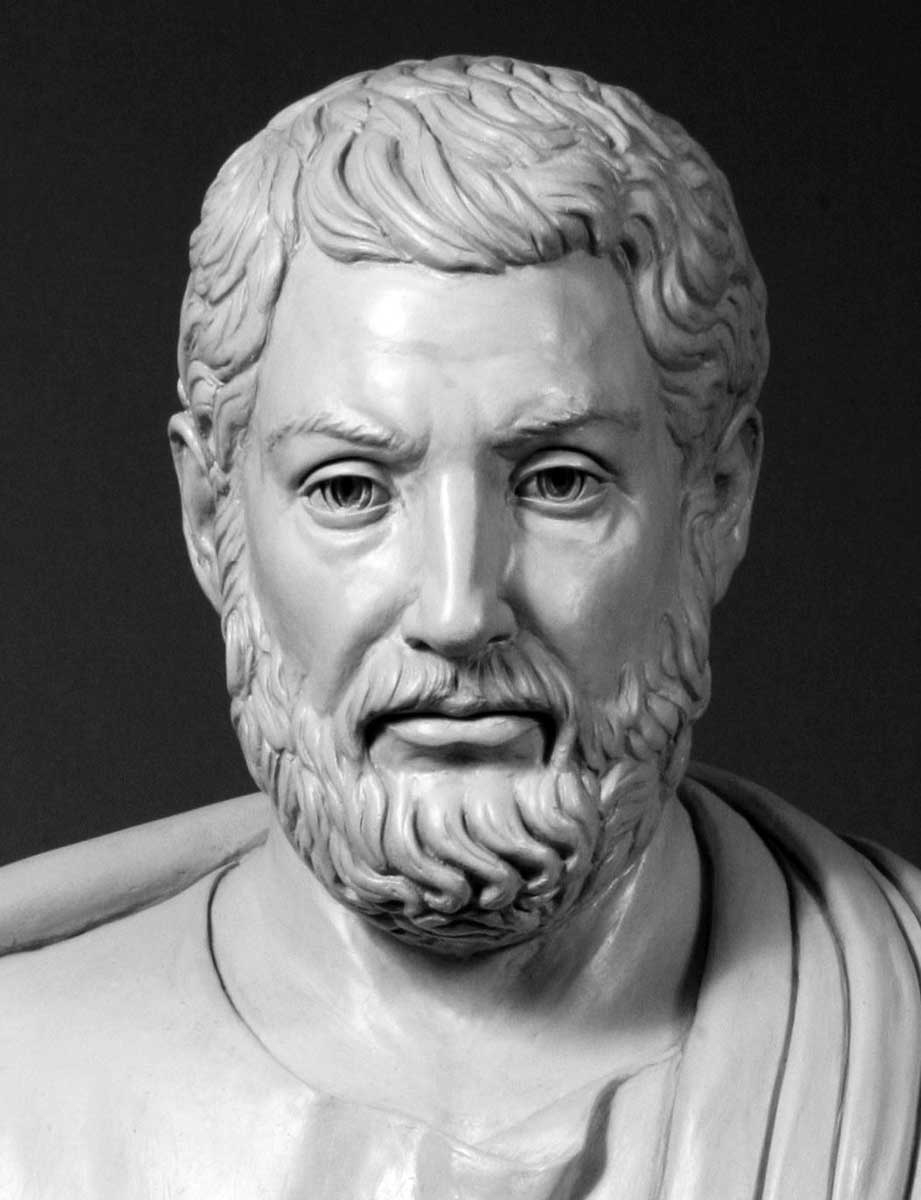

While this may seem like a bizarre law and one that could be prone to exploitation, it made sense when considered in the context of the political instability of the 7th and 6th centuries BCE. It was the symbolic and ritualized manifestation of the people’s power. It was used relatively few times in Athens’ history, one of them being against the statesman Themistocles, one of the leading generals from the Persian Wars.

Political Strife in the 7th & 6th Centuries BCE

In the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, widespread political instability prevailed throughout the Greek world. The basic political unit of the city-state, or polis, was the tribe. Aristocratic families dominated these tribes, and the leading families wielded immense political power in the polis. Citizenship was based on membership in a tribe, and to be excluded from a tribe meant no longer being a citizen of the polis.

The aristocratic class, being the only ones eligible for state office, contended with each other for leadership roles. With their tribes at their backs, the competition for the highest offices turned into factionalism and violence. Those who gained power would exile the rival faction and seize control of their properties. The exiled faction was then motivated to seek aid in returning to the polis to oust their enemies. Some of the more prominent families had powerful foreign connections, such as the king of Sparta.

Such was the situation in Athens. Solon, one of the Seven Sages of Greece, attempted to correct the situation with his reforms. But once he was out of office, the status quo of politically motivated exile resumed.

A nephew of Solon, Peisistratus, eventually gained power and, through popular support of the non-aristocratic class, installed himself as tyrannos, or tyrant. This didn’t necessarily mean he was a despot. The original meaning of the word was to differentiate how political power was attained, in the same way that king, chancellor, and president describe the highest political office of their respective governmental system. Tyrants gained power outside official means provided by the constitution of the polis. While the word eventually came to be regarded in the same manner as it is today, Peisistratus was, by all accounts, a good and just leader.

The Rise of Tyrants

The significance of Peisistratus using popular support to gain power was that it marked one of the first instances in Athens where the non-aristocratic class asserted its own power in the political arena. When Peisistratus came to power, instead of exiling his rivals as was the norm, he allowed them to remain in Athens and even to have important political roles. By allowing his rivals to remain in the polis and lead their lives as normal, he eliminated the threat of factions returning with foreign aid to attack the city. It also meant that if any aristocratic families tried to force him from the polis, they would be opposed by Peisistratus’ non-aristocratic supporters.

Under Peisistratus, the city’s political situation stabilized. His son, Hippias, however, didn’t learn the lessons of his father. When his brother Hipparchos was murdered, Hippias became truly tyrannical. He executed the assassins, who were later revered as Tyrannicides, exiled political rivals, and became bitter towards the Athenian citizens as a whole.

Hippias was overthrown a few years later, and power returned to the aristocratic class. The two most prominent factions were led by Cleisthenes and Isagoras. The two competed for power, but Isagoras was ultimately elected as archon. Cleisthenes turned to the populace for support, but Isagoras appealed to the Spartan king Cleomenes, who marched an army into Athens and expelled Cleisthenes and his closest supporters from the city.

Isagoras and Cleomenes then attempted to dissolve the Athenian Council, which oversaw the city’s day-to-day affairs, and sought to establish an oligarchy of their own allies. The Council resisted, and the common people threw their support behind them, rising up against Isagoras and the Spartans, who fled up to the Acropolis. They were besieged there for three days until the Spartans eventually signed a truce and were allowed to leave. Many of Isagoras’ closest supporters were taken into custody and executed. This marked the moment when the people of Athens officially took control of the city for themselves.

Cleisthenes was recalled from exile and was given leadership of the polis. He immediately undertook an extensive program of constitutional reform, during which he established several institutions that transferred political power to the people.

How Did Ostracism Develop? Reforms of Cleisthenes

Ostracism was developed to check the ambitions of any would-be tyrants, but it also had greater symbolic meaning within the newly developing democracy. Until Cleisthenes’ reforms to the Athenian constitution, power was held by a select few members of society. That power was not just to legislate but also to determine who would be included and excluded from society. The true exercise of state power was the ability to exile rivals, and the excessive use of this power contributed to the instability of the polis during the 7th and 6th centuries.

Cleisthenes’ reforms aimed to curb the factionalism and aristocratic power struggles that had dominated the previous centuries. He first changed the citizenship requirement. Rather than needing to be part of a tribe to be a citizen of the polis, one now had to be enrolled in the lists of a deme, a geographic subdivision of Attica, much like a neighborhood. He then expanded the number of tribes from four to ten, and divided the demes into the new tribes, thereby basing political power and identity on geographical residence rather than kinship. The Council was expanded from 400 to 500, and government positions were filled by lot instead of being hereditary or based on family relations. Then there was the introduction of ostracism.

Cleisthenes called his reforms isonomia, meaning equality under the law, rather than democracy.

Procedure for Ostracism

There were several steps involved in conducting an ostracism. The first step was for the Athenians to decide whether or not to hold an ostracism. In the sixth month of their ten-month year, the assembly asked whether they should hold an ostracism that year. If a majority agreed, a vote would be held two months later.

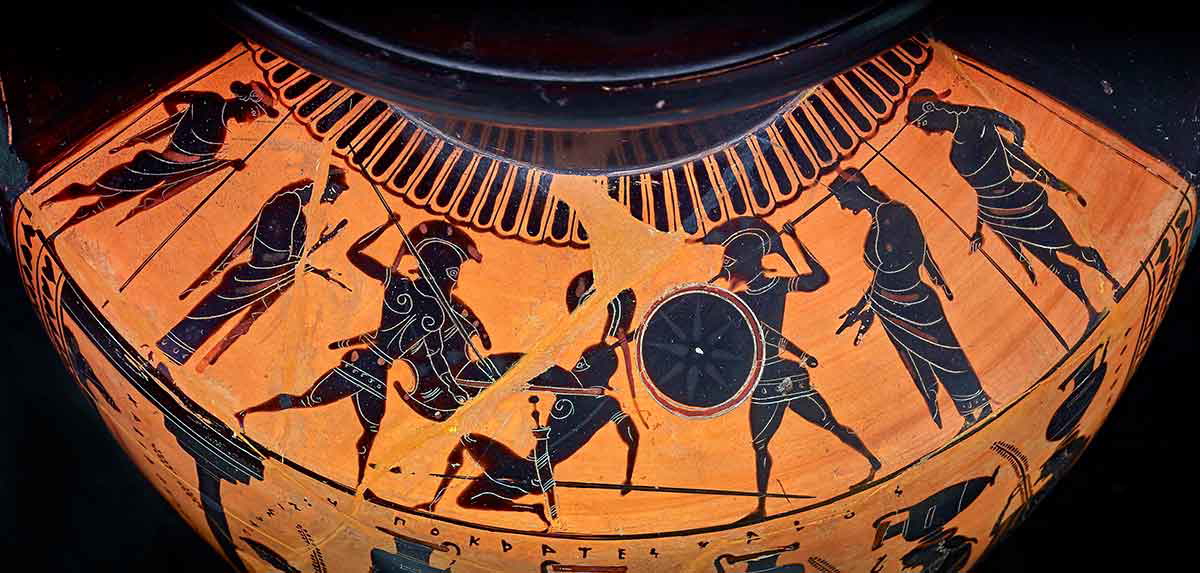

In the agora, a section was designated for citizens to cast their votes. They scratched names onto potsherds, called ostraka, which were usually recycled from broken vessels. Some people also broke their own vessels by smashing them on the ground in a show of performative aggression. Once the names were scratched onto the potsherd, they were then thrown into the cordoned-off area in the agora, where they were counted and tallied. The ostracism would only be considered valid if 6,000 people voted, and then the ostracized person would have ten days to leave the city. They had no chance to defend themselves or to appeal the decision.

Ostracism as a Democratic Tool

While ostracism may seem odd and has often been cited by those with anti-democratic sentiment as one of the detriments of democratic rule, the law served as a practical reminder of the people’s power in the political life of the polis. Through the institution of ostracism, a peaceful solution was found to aristocratic factionalism. By posing the question to the assembly each year, the aristocracy was reminded that the people were the final arbiters of political power in the polis. Anyone who accumulated too much influence or whose power was not based on the consent of the people could be exiled at will.

In the roughly 100 years when the law was actively in use, there were only nine firmly attested ostracisms. It stood in stark contrast to the often violent and excessive use of exile before Cleisthenes’ reforms. By imposing a fixed term for the exile, maintaining property rights, and employing the institution sparsely, the Athenians both stabilized the polis and legitimized their democracy.

Historical Cases

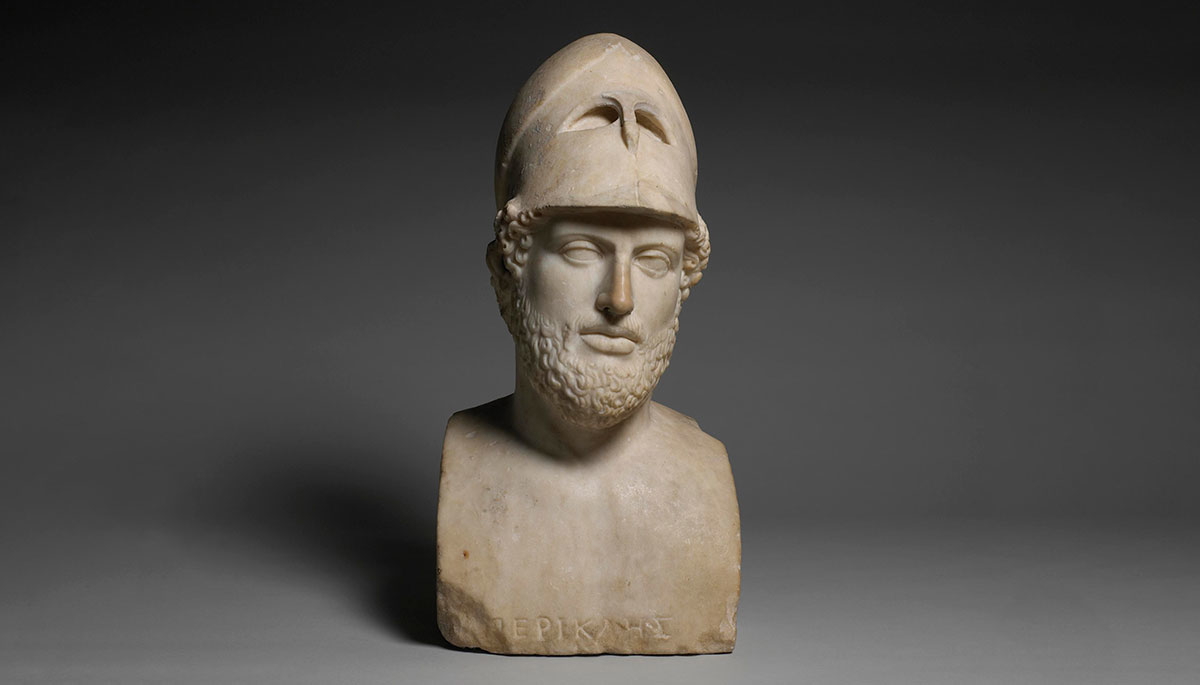

The first recorded use of ostracism occurred 20 years after its inception, against Hipparchus, a relative of the Peisistratid tyrants. The next man ostracized was Megacles, a nephew of Cleisthenes. Some of the reasons scratched onto the ostraka referenced his wealth and love of luxury. The third man exiled was another friend or relative of the Peisistratid tyrants. The next instances of ostracism were against Xanthippus, the father of Perikles, and Aristides. Both of these men were rivals of Themistocles for political leadership.

Themistocles himself was ostracized in 472 BCE. According to Plutarch, Themistocles had become arrogant in his own prestige, and people were tired of hearing him speak of his achievements. The Spartans were also helping to promote Themistocles’ political rival, Cimon, who supported pro-Spartan foreign policy. Cimon was later ostracized in 461 BCE. He lost influence after he had convinced the assembly to help the Spartans deal with a helot revolt, but the Spartans turned them away for fear that the Athenians would side with the helots.

There were other ostracisms throughout the 5th century BCE, such as that of Thucydides, a political opponent of Pericles. The final recorded ostracism was in 416 BCE against a man named Hyperbolus. He was not part of the aristocratic class, nor did he seem to have much political influence, but he was not well-liked and was often the butt of jokes. During the ostracism for that year, the men likely to be selected for exile were Nicias, Alcibiades, and Phraeax. To prevent their expulsion, Alcibiades and Nicias convened a conference and united their factions to ostracize Hyperbolus.

The institution was discredited afterwards, both because it was used against a non-aristocrat when its purpose was to curb aristocratic political ambition, and because it was openly manipulated. From then on, the question of whether to have an ostracism continued to be asked in the assembly, but it was never used again.

Select Bibliography

Forsdyke, S. (2000) “Exile, Ostracism and the Athenian Democracy,” Classical Antiquity, 19(2), 232–263.

Kagan, D. (1961) “The Origin and Purposes of Ostracism,” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 30(4), 393–401.

Kirshner, A. S. (2016) “Legitimate Opposition, Ostracism, and the Law of Democracy in Ancient Athens,” The Journal of Politics, 78(4), 1094–1106.

Paul J. Kosmin. (2015) “A Phenomenology of Democracy: Ostracism as Political Ritual,” Classical Antiquity, 34(1), 121–162.