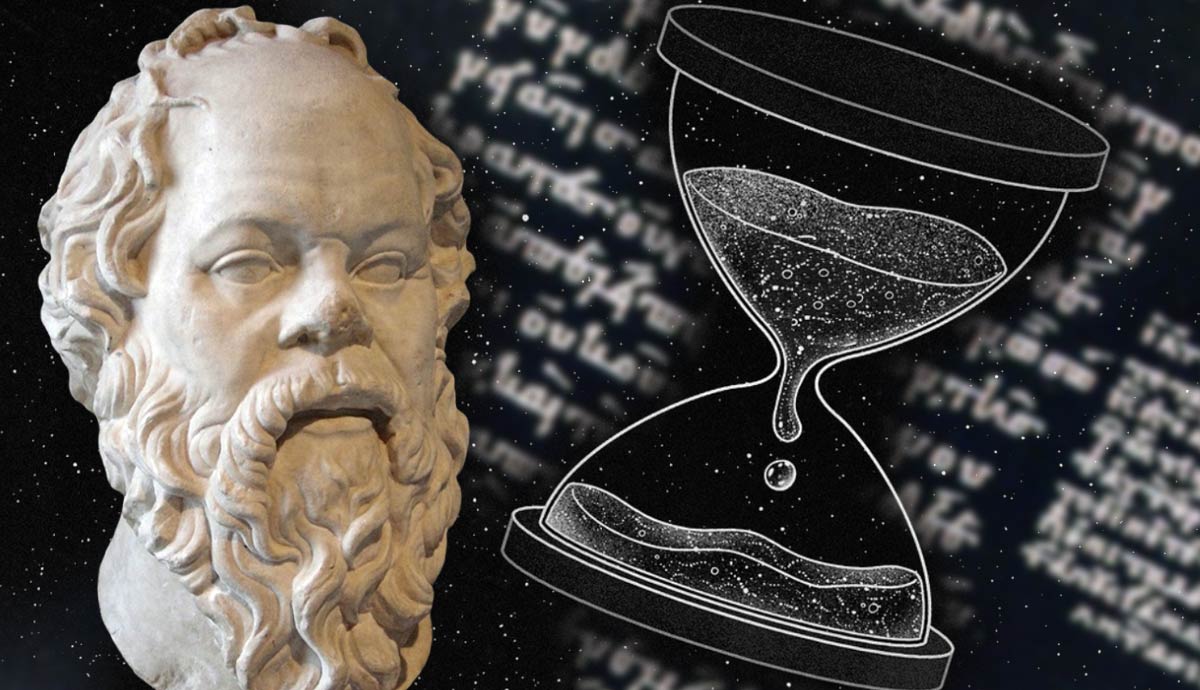

Plato once suggested that time itself might be an illusion. In his dialogue Timaeus, he called time “the moving image of eternity,” a cryptic phrase that has puzzled philosophers for centuries. Was Plato hinting that everything we experience (days, seasons, even history) is nothing more than a shadow cast by a timeless reality? In this cosmic account, Plato explores how the world of motion and change reflects, however imperfectly, the eternal realm of unchanging truth. By following his vision, we step into the mystery of how time mirrors eternity.

The Creation of the Cosmos in Plato’s Timaeus

Plato’s tale begins with a shadowy figure: the Demiurge, the divine craftsman. From the swirling chaos, he carved order, shaping the universe according to the eternal Forms, those flawless patterns that exist beyond time. Yet the world he fashioned could never equal their perfection. It became only a mirror, a beautiful but flawed reflection of eternity.

And with that reflection, something else stirred into being: time. In Plato’s vision, time was never a fundamental reality, but a moving image of the eternal, set in motion by the Demiurge’s design.

Time and Eternity in Plato’s Metaphysics

Plato drew a sharp line between two realities. The physical world belongs to the realm of Becoming (ever-changing, restless, imperfect). The realm of the Forms, by contrast, belongs to Being (timeless, motionless, and perfect). Time itself belongs to Becoming. It flows, it changes, it measures the restless motion of the universe. Eternity, however, belongs to Being. It simply is. No past, no future, only a still and changeless present.

To understand what Plato really meant when he called time the “moving image” of eternity, we must first grasp this haunting vision of eternity as something outside of time altogether.

The Nature of Eternity According to Plato

The nature of eternity in Platonic philosophy has been the subject of extensive scholarly debate. The major point comes down to whether the term ‘eternity’, for Plato, is durational or not. In other words, does ‘eternity’ denote timelessness or everlasting duration (i.e., sempiternity)?

Some scholars, like Richard Sobarji, even argued that “Plato did not decide between making eternity timeless and giving it everlasting duration” (Sobarji, 1983). Although there is yet to be a general consensus on Plato’s definition of ‘eternity’, we can find some hints in Timaeus.

In Timaeus, Plato describes the difference between ‘Being’ and ‘Becoming’ as the difference between that which always ‘is’ and that which ‘was’ and ‘will be’. He argues that we can only refer to ‘Being’ in the present tense, as that which ‘is’, whereas “was and will be is fittingly said of Becoming”. Plato explains that such is the case because “was” and “will be” are motions, which cannot pertain to the motionless nature of ‘Being’.

Eternity, as the state of the Forms, is necessarily motionless and unchanging. Sempiternity, or everlasting duration, entails a temporal succession, even if the succession extends ad infinitum. According to Victor Ilievsky’s analysis, this suggests that eternity cannot be durational. Instead, eternity must necessarily denote an atemporal present. As he explains, “Plato’s concept of eternity presented here is that Plato conceived of it not as infinite duration (sempiternity), but as timeless, unchanging present (eternity proper)” (Ilievsky, 2015).

Time as the Moving Image of the Eternal

In Timaeus, Plato describes time as the moving image of the eternal, which is the timeless and unchanging state of the intelligible realm of the Forms. He explains that it is, “made of that eternity, abiding in unity, an eternal image moving according to number, that which, in fact, we have been calling time”. Time, as an image (i.e. reflection) of eternity, is described to move according to number. Some scholars argue that Plato identifies time with motion, while others argue that he identifies it with number.

However, describing time as a “moving image” does not suggest that time is motion, but that time is in motion. Furthermore, the movement of time “according to number” does not mean that time is identical to number, but refers to the movement itself. Hence, in Plato’s aforementioned quote, “time is the subject which is characterized by, or has motion as its attribute, the latter being not random or erratic, but according to number, i.e. regular” (Ilievsky, 2015).