The Battle of the Greasy Grass, also known as the Battle of Little Bighorn, fought on June 25, 1876, is eternally etched in America’s consciousness. Viewed in various contexts in the decades since its occurrence, the fight is nonetheless one for the history books. Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors earned one of the biggest victories over the US Army, wiping out the entirety of George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry. The decisions made leading up to and during the event would determine the fates not only of the warriors on the field but the future of US-Indian policy. Who called the shots at the Greasy Grass?

1. Crazy Horse

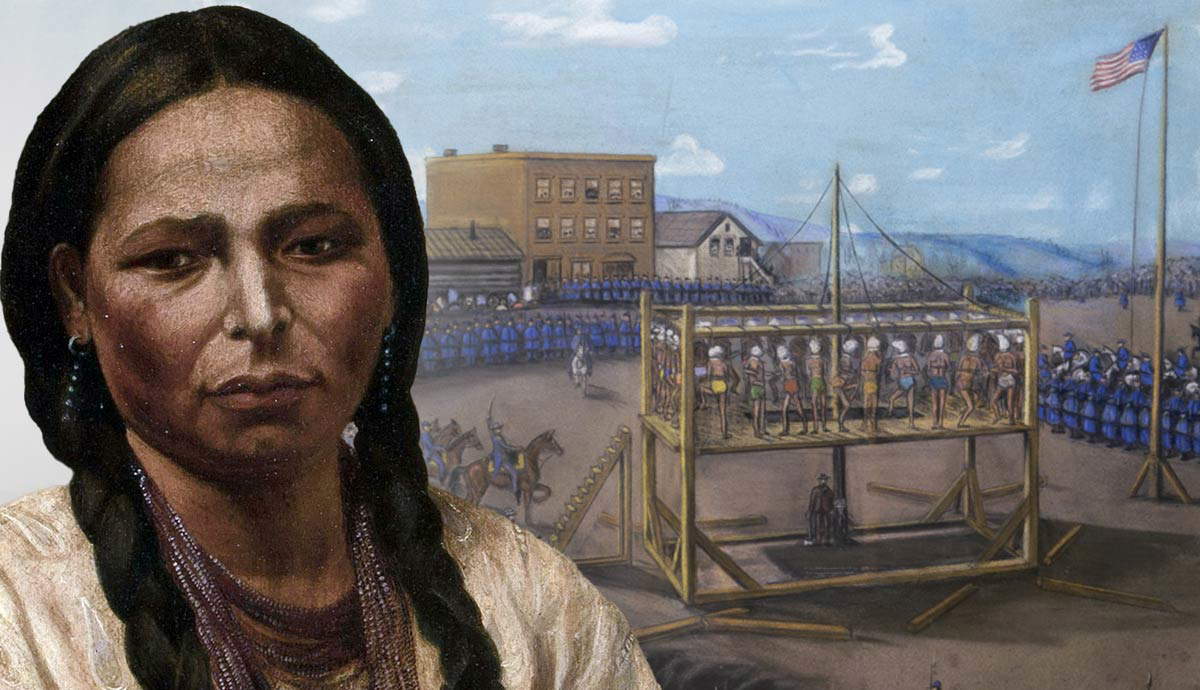

Born Chan-O-Ha or “Among the Trees,” Tansuke Witco, or “Crazy Horse” (more accurately translated as “His Horse is Crazy”), earned his father’s name after filling his early teen years with multiple cultural and military accomplishments. He proved himself an exceptional warrior in inter-tribal warfare and was promoted to the position of Shirt Wearer, a designation reserved for the best of the best of Lakota soldiers.

In the mid-19th century, the main enemy of Crazy Horse’s people became the encroaching United States. Crazy Horse was heavily involved in the series of conflicts known as Red Cloud’s War, including Fetterman’s Fight, or The Hundred in The Hands, where he led the decoy trap that lured Captain William Judd Fetterman and his men to their deaths. Though Crazy Horse was a quiet man and thought strange by some, his actions to care for those who were struggling in his community, such as widows and the elderly, demonstrated his dedication to his people. He appeared to be a fearless leader who encouraged his fellow warriors to follow him into battle with the cry “Hokahey [similar to “let’s go”], today is a good day to die!”

Crazy Horse was instrumental at the Greasy Grass, acting as a key leader among more than 1,500 allied Indigenous warriors. Just days prior, he had successfully led 1,200 warriors against General George Crook at the Battle of the Rosebud (also known as Where the Girl Saved Her Brother). Defeating the Americans soundly, Crazy Horse continually refused treaties and reservation life. He was arrested in May 1877 and taken to Fort Robinson, where he was killed by officers later that year.

2. George Armstrong Custer

Perhaps one of the most controversial figures in American history, George Armstrong Custer has been both celebrated and vilified in the years since his death. Custer was a rambunctious West Point student, later active in the Civil War, earning the rank of major general. He was known for his bravery and bravado, along with his flowing blonde locks. The Indigenous people he encountered in battles on the Plains often referred to him as “Yellow Hair.” Interestingly, Custer would chop his famous mane just before the battle that would seal his fate at Little Bighorn, making it difficult to identify his body.

Working with generals Crook and Terry, Custer led one arm of a planned three-prong attack on the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho camp. The goal was to subdue the “non treaty Indians” who refused to move to the reservations that were being established by the US government. Custer arrived at the planned meeting location first and, believing the numbers of warriors in the Native American village were smaller than they actually were, elected to attack without waiting for supporting forces. Custer also lacked supplies, as his pack train was delayed. Still, the confident Custer advanced, leading just over 200 US soldiers in an assault on the village, which contained thousands of Indigenous men, women, and children, and among them, over 1,500 skilled warriors.

He’d lend his name to the event in the immediate aftermath, with the battle referred to as “Custer’s Last Stand” in the press. He was further glorified by the publication of multiple bestselling books written by his wife, Elizabeth “Libbie” Custer. Even in the early 20th century, the Custer myth persisted, with films like Custer’s Last Stand and They Died With Their Boots On starring Errol Flynn, who portrayed the soldier as a sympathetic character. In recent years, however, other perspectives have been pushing through the narrative, and the truth of Custer not only attacking a village but impulsively leading his men to their deaths has become a point of discussion.

3. Sitting Bull

Though he was beyond fighting age at the time of the Greasy Grass, Sitting Bull was instrumental in the success of the Lakota in the fight. An esteemed tribal elder and medicine man, the warriors looked to Sitting Bull for leadership and inspiration. Two weeks before the fight, Sitting Bull had a dream in which white soldiers were falling upside down into the Lakota camp “like grasshoppers,” symbolizing their deaths. Though he would not personally fight in the battle, Sitting Bull was present in the camp and sent his two nephews, One Bull and White Bull, into battle with his own personal medicine.

4. Frederick Benteen

Frederick Benteen was a captain in the 7th Cavalry, and not long after his appointment, he developed a loathing for his commanding officer, George Custer. He did not like Custer’s tendency for self-promotion or his showy manner. At Little Bighorn, Benteen was sent southwest to scout for additional Native encampments, but he found none and turned to head back. It was then that a message arrived from Custer’s camp informing him that Custer had engaged the enemy.

The message ordered Benteen to come quickly and to bring the pack train he had with him, as it contained extra ammunition. However, on his way back, Benteen encountered the company of Major Marcus Reno, who had been pinned down by Native warriors. Instead of following Custer’s orders, Benteen remained with Reno. About 350 members of the 7th Cavalry survived that encounter. Benteen was criticized by some for failing to support Custer but was considered by many to have “saved the day” for Reno’s forces.

5. Gall

Gall, whose actual name was Phizi or “Man Who Goes in the Middle,” was a Hunkpapa Lakota orphan whose tenacity and skill proved his merits as a warrior early in life. He was a favorite Protégé of Sitting Bull and had a reputation as a survivor. In addition to overcoming a rough start in life, in 1865, an Arikara scout, Bloody Knife, led US soldiers to Gall’s encampment, where Gall was bayoneted and left for dead. He crawled away and made a full recovery. Gall led the assault on Major Reno’s men near Little Bighorn, then returned and assisted Crazy Horse and others in directing the fight against Custer’s forces.

6. Marcus Reno

Considered second-in-command after Custer at the Greasy Grass, Major Marcus Reno never made it to the famous battle site. Instead, his approximately 140 men were pinned down when they attempted to broach the Native village under Custer’s orders. The attack quickly became a retreat, then a siege, forcing Reno and his men to remain in place while Custer’s contingent was wiped out. After the smoke cleared, Reno was instantly scrutinized for what some considered his failure to assist Custer. A court of inquiry, including 1,300 pages of testimony, eventually exonerated him three years later, but his reputation, coupled with rumors of alcoholism (he was even accused by some of being drunk during the attack), meant his good name would never be restored. His military career spiraled downward, and he was eventually dismissed from the army. He continued trying to clear his name but was largely unsuccessful before he died of throat cancer in 1889.

7. Bloody Knife

Perhaps the most famous “Indian Scout” to serve with the US Army, Bloody Knife, was the son of a Hunkpapa Lakota man and an Arikara woman. He felt out of place in both tribes and, as a child, he was constantly ridiculed due to his mixed parentage. Bloody Knife enlisted as an Indian Scout during the Civil War and continued his involvement with the army afterward. He became a favorite of George Custer, and he accompanied him on many assignments. Bloody Knife was assigned to assist Reno as the conflict at the Greasy Grass ramped up, and he was killed by a bullet to the head as he stood beside Reno, discussing strategy.

Recommended Reading: Connell, Evan S.(1984). Son of the Morning Star. New York: North Point Press