Inspired by Victorian fascination with childhood imagination and the absurd, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland opens with a moment of childish curiosity that propels Alice into a world where logic, identity, and authority are constantly questioned. As Alice journeys through Wonderland (from the nonsensical Mad Tea Party to the chaotic Queen’s croquet game and the farcical trial of the Knave of Hearts) she encounters a series of characters and scenarios that challenge her understanding of reality. These episodes not only reflect Carroll’s background in math, theology and logic, but also chart Alice’s psychological and philosophical growth.

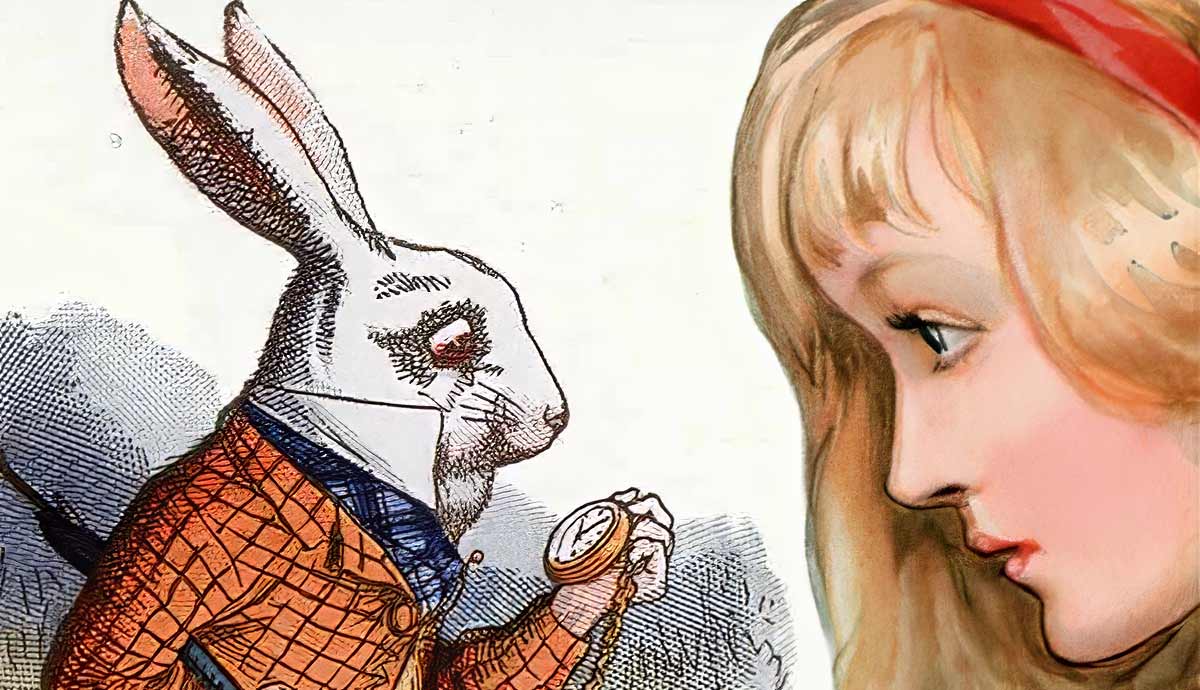

How Alice Gets to Wonderland

Alice enters Wonderland through a moment of impulsive curiosity, reflecting the imaginative spirit of Victorian childhood as captured by Lewis Carroll. While sitting by the riverbank, she notices a frantic White Rabbit and, intrigued by his strange behavior, follows him down a rabbit hole. This descent marks her departure from the structured adult world of logic, into a realm where language twists, identity blurs, and meaning constantly reshapes itself. Her fall is both literal and symbolic, initiating a journey through a surreal landscape that mirrors the era’s fascination with dreams, nonsense, and the playful subversion of adult authority.

The “Drink Me” Potion and “Eat Me” Cake

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the “Drink Me” potion and “Eat Me” cake serve as surreal catalysts for Alice’s shifting identity. These size changes reflect not only the instability of adolescence but also the influence of Romantic and Gothic traditions, where altered states and dreamlike logic challenge rationality. Lewis Carroll’s playful subversion of scale and logic aligns with early absurdist impulses and prefigures the whimsical distortions of later Surrealist art, inviting readers to question the reliability of perception and the rules that govern reality.

Alice Meets with the Caterpillar, Cheshire Cat, and Mad Hatter

As Alice continues her exploration of Wonderland, she encounters many symbolic characters. Most famously, the Caterpillar, Cheshire Cat, and Mad Hatter. They reveal Wonderland as a space where identity, logic, and language unravel. The Caterpillar’s languid, opium-smoking presence evokes Orientalist imagery and 19th-century British fascination with Eastern mysticism and altered states.

The Cheshire Cat’s disembodied grin and paradoxical logic prefigure Surrealist art and challenge Enlightenment ideals of coherence, while the Mad Hatter’s chaotic tea party satirizes social conventions and time itself. Together, these meetings expose Wonderland as a dreamlike realm shaped by colonial imagination and the psychological distortions of a world in flux.

The Mad Tea Party and the Queen’s Croquet Game

The Mad Tea Party and the Queen’s croquet game, which occur in the middle chapters of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, reveal the surreal logic that governs Wonderland by distorting familiar rituals. The tea party, which Alice stumbles upon, mocks ideas of reason and civility through nonsensical riddles, frozen time, and warped etiquette. Later, in the Queen’s Garden, the croquet game parodies hierarchical power structures, with flamingos as mallets, hedgehogs as balls, and rules that shift according to the Queen’s whims.

These scenes reflect Victorian anxieties about arbitrary authority and social order, while also engaging with philosophical absurdism and Freudian notions of the unconscious disrupting logic. Carroll’s playful use of nonsense literature invites readers to question the stability of meaning, identity, and control.

The Knave of Hearts’ Trial and Alice’s Reaction

The Knave of Hearts’ trial, which occurs near the end of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, marks the climax of Wonderland’s absurdity and triggers Alice’s return home. The trial parodies legal proceedings, with nonsensical evidence and arbitrary rules, reflecting Victorian critiques of institutional authority and foreshadowing Kafkaesque themes of bureaucratic chaos.

As Alice grows in confidence, she challenges the Queen’s irrational commands and the court’s illogical reasoning, asserting her own sense of justice. Her defiance aligns with psychological theories of maturation, particularly Freudian ideas of ego development. As she declares “You’re nothing but a pack of cards,” the illusion collapses, returning her to reality.