In Christianity, relics are objects or articles of religious significance from the past. These items tend to be parts or fragments of a larger object that no longer exists and may include body parts of saints or holy persons (someone who has been beatified or canonized), their belongings, or something they have touched. In the Catholic tradition, relics are featured prominently and venerated. Every Roman Catholic Church has at least one first-class relic located under the main altar where the mass is presented.

Classes of Relics

In Catholicism, relics are divided into one of three classes. The classification of a relic depends on how closely it is associated with the saint. The first class of relics is an object closely related to Jesus, such as a piece of the cross, or a physical body part of a saint such as a vial containing blood, a tooth, or a bone.

The second class of relics are objects the saint owned or regularly used. Examples would be clothing, religious artifacts, or books.

Third-class relics are those objects that came into contact with a higher-class relic and therefore constitute a more distant connection to the saint. Examples are accessories like rosaries, medals, crosses, oil, or water that touched a saint or a holy artifact and have been blessed by a priest afterward.

The History and Necessity of Relics

Some early Christian churches were built on catacombs or graves that held the remains of martyrs. These structures were generally constructed to memorialize the relevant saint(s) and the relics were thus considered part of the structure. Pilgrims who traveled to far-off religious sites would at times bring back relics for use in newly constructed structures that would serve as a memorial to a saint. It became part of ecclesiastical practice to incorporate relics in each building.

It became Roman Catholic canon law that each structure, whether church or cathedral, with an altar for communion, must have a relic in or under the altar. The relics placed on the altars of churches and cathedrals are generally placed in the altar’s base and sealed to prevent theft or desecration.

This requirement means that first-class relics must be available for each newly constructed cathedral or church. The Catholic Church holds relics in store for that and other purposes. One such repository of relics is in the Diocese, or Vicariate, of Rome. Some relics are kept in containers called reliquaries or lipsanoteca which can take many shapes and forms and often reflect the culture the relic hails from. These can range from large glass containers which allow for open display of the relic to small containers that preserve a fragment of significance.

Relics in Medieval Christianity

Though the practices of accumulating and preserving relics are common today, the significance of relics in medieval Christianity is notable. Possessing a relic brought honor and privilege to the owner and the veneration of relics rivaled the sacraments in the lives of many believers. They believed that relics held miraculous powers such as healing the sick or preventing disasters, which made them sought-after objects.

Most relics were found in the Holy Land or in Italy, where the seat of the Roman Catholic Church was, and the church in Europe grew much faster than the supply of relics. With the occupation of the Holy Land by Muslims for much of medieval times, Rome became the primary source of relics during those times. Crusaders would, at times, return from their crusades in the Holy Land with treasure troves of relics to supply to eager buyers.

Merchants, often of ill repute, would also loot catacombs and offer relics for sale. Arguably the most notorious relic merchant and swindler was Deusdona, a Roman deacon, who ran a family business of stealing relics in Italy and smuggling them to various parts of modern-day Germany.

Possessing a relic meant increased pilgrimages to the church or cathedral that owned the relic, which translated into increased funds entering the coffers of the local diocese. In some instances, relics were stolen from one church only to resurface in another sometime afterward. The high value and demand for relics in the Medieval Period gave rise to a black market where objects of religious significance could be bought and sold.

The problem with relics at that time was one of authenticity. Technology did not yet exist to scientifically verify which relics were authentic and which were not. One thing that convinced people of the authenticity of a relic was the accompanying miracles that were claimed to result from exposure to a relic. If a person was healed when exposed to a relic, the relic must have been authentic—or so common belief held. The witness of the miracle would serve as marketing, drawing many others to visit the relic in search of their own miracle or just to have the honor and experience of being exposed to it.

Case in Point

Thomas Becket was the archbishop of Canterbury in the 12th century. Becket and King Henry II started as friends but as Becket ascended the hierarchy of the church and became Archbishop, he opposed Henry’s attempts to gain authority over the Church. Four knights, allegedly misinterpreting an utterance by King Henry II, slew Becket in the Canterbury Cathedral. After his death, many miracles were reported from the surrounding area and some individuals who visited his tomb claimed to have been healed. Word of these miraculous phenomena reached Rome, and the pope declared Becket a saint.

As a result, Canterbury became one of the most popular sites for pilgrimages. Monks would offer vials with St. Thomas’s blood for sale to those who visited the cathedral. It brought a significant income for the diocese and contributed to its prosperity. The blood was diluted with water to increase the volume of what could be sold and increase profits. Though the blood was diluted, the efficacy of the blood was reportedly not diminished at all.

Effect of Relics on Medieval Christianity

Because of the belief that relics held miraculous power, many people desired to have exposure to them or even to own some. The sales of relics became a significant source of revenue for the Catholic Church, as Christians from all over Europe would travel vast distances in search of the blessing, protection, and healing believed to come from the relics.

Unfortunately, the popularity of relics and the potential they held to raise money resulted in a large amount of fakes flooding the market. Due to the low level of education of most of the medieval population, it was not difficult for swindlers to pass off fakes as authentic. There was little to no technology available at the time for authentication and believers had to rely on the word of clergy and merchants, which was in itself not reliable at all.

The proliferation of fake relics became such a problem that it had to be addressed at the Council of Trent. The council declared that Bishops had to verify and authenticate relics more rigorously to curb the distribution of fakes.

Martin Luther’s close associate and protector, Frederick III of Saxony, also known as Frederick the Wise, owned a large collection of relics. It contained pieces associated with saints and biblical figures, straw from Jesus’s manger, fragments of the True Cross, and the bones of saints. His collection of more than 19,000 items was one of the largest in Europe.

Considering this, it is remarkable that Frederick remained a supporter of Martin Luther after the latter’s excommunication and in the light of his opposition to the veneration of relics. The role of relics in Protestant Christianity diminished significantly as Luther opposed it alongside the selling of indulgences.

Reliquaries or Lipsanoteca

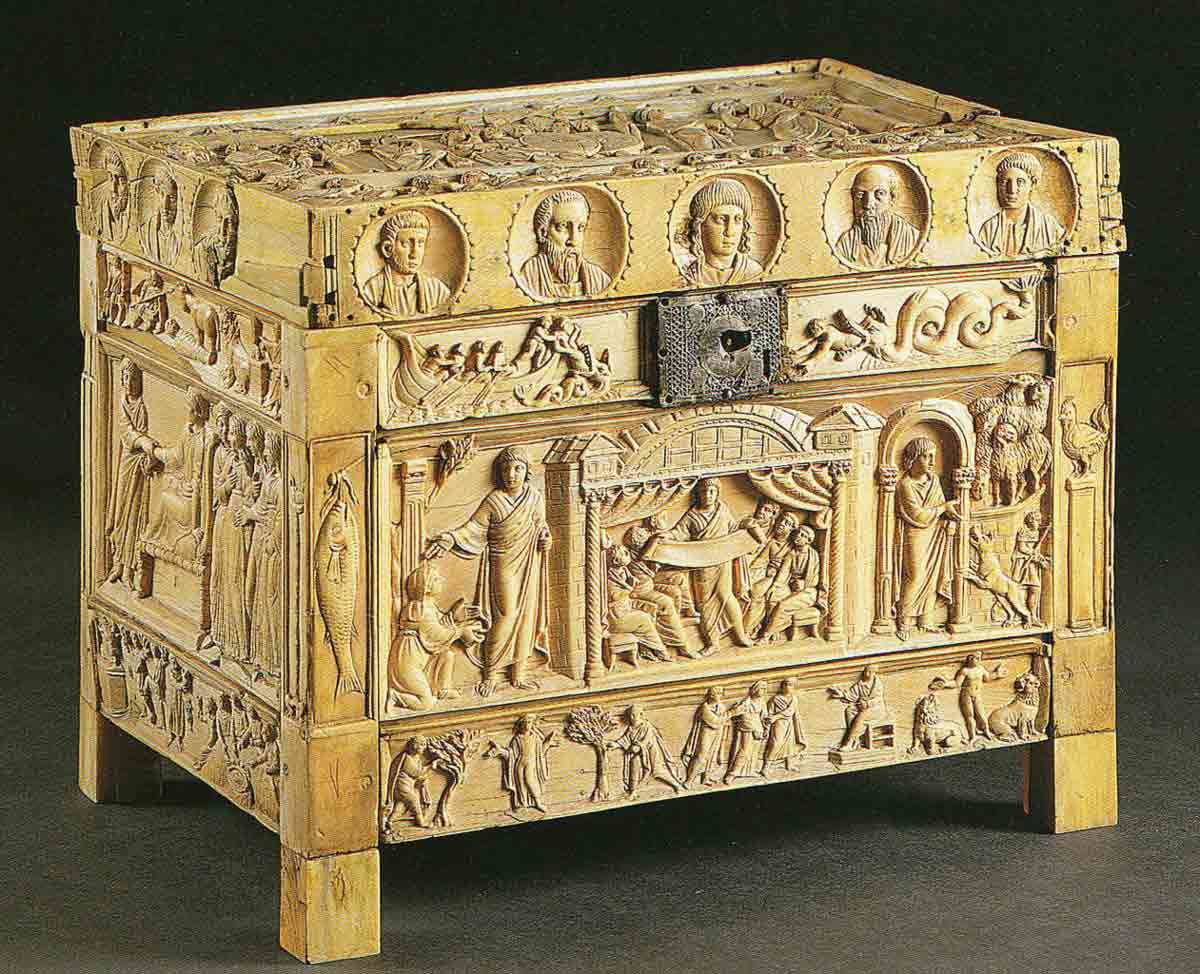

Because relics were so valuable and were often on display for pilgrims, they were usually kept in reliquaries or lipsanoteca. These cases were generally adorned with elaborate artwork. Lipsanoteca has the same meaning as a reliquary but refers to a small number of reliquaries from the 4th century made of ivory with the Brescia Casket being a prime example. The lipsanoteca in Cappella delle Reliquie of the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna is an altarpiece that holds many reliquaries.

Though most relics tend to be fairly small, some consist of the whole body of a saint. Such is the case with Hyacinth of Caesarea. He was a young Christian who lived at the beginning of the 2nd century and served as an assistant to Emperor Trajan’s chamberlain. When he refused to take part in pagan ceremonial practices, he was imprisoned and only offered food sacrificed to the pagan gods. He refused to eat it and starved to death in 108 CE at the age of twelve, believing it was not permitted for a Christian to eat such food. His remains are on display in a glass case in the Church of the Assumption, the church of the former Cistercian Fürstenfeld Abbey in Bavaria. The remains are elaborately decorated with jewels. His body is one of the most complete relics in Christianity.