Following Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BCE, his former generals and governors fought for control of his empire. Almost two decades later, the Antigonid family, headed by Antigonus Monophthalmus and his son Demetrius, had just declared themselves kings and looked best placed to come out on top. When they turned their attention to Rhodes, the small democratic island was hopelessly outmatched. For a year, both sides fought with remarkable determination and the height of military technology in a battle that was to be remembered.

Rhodes and the Diadochi

More than a decade on from the death of Alexander the Great, his former generals and governors were still locked in the struggle to control the empire. After several rounds of fighting, Antigonus Monophthalmus and his son Demetrius had risen to the top. Not only did they control the largest part of the empire, but following Demetrius’ victory over their rival Ptolemy on Cyprus in 306 BCE, the father and son declared themselves kings. They were not invincible, as a failed invasion of Ptolemy’s Egypt went on to show, but they were the most powerful force since Alexander himself.

In contrast, Rhodes was just a small island in the south-east Aegean Sea which had not yet played a significant role in Greek history. In the late 5th century, the previously divided Rhodians formed a single community and built a new city called Rhodes on the northern tip of the island. With the new city built on a series of hills and with five harbors, it was well-placed to become a center of commerce. Still, the Rhodians continued to be a minor state going through a series of internal upheavals as oligarchic and democratic factions fought for control.

By the end of the 4th century, Rhodes had grown to be a major commercial and naval power. This allowed the Rhodians to become a “clearinghouse and banker of the eastern Mediterranean” (Berthold, 1984, 50). Wealthy and under a moderate democratic constitution, Rhodes was referred to as the best-governed state in Greece (Diodorus 20.81.2). After freeing themselves from Macedonian control on the death of Alexander, the Rhodians maintained a policy of neutrality. In 305 BCE, however, the wars raging around them came to Rhodes.

Rhodes Is Drawn Into War

Rhodes occupies a strategic location between Greece, Syria, and Egypt. Key to their commerce was the grain trade with Egypt. The subsequent strong relationship with the current ruler of Egypt, Ptolemy, created tension with the Antigonids. The threat became particularly acute following Demetrius’ campaign in Greece. Suddenly, Rhodes’ favorable location left it uncomfortably between the centers of Antigonid power in Greece and Syria (Wheatley & Dunn, 2020, 179). With the Antigonids and Ptolemy at war, the Rhodians tried to maintain their policy of neutrality, but the pressure grew. In 306 BCE, they understandably refused to provide ships for Demetrius’ campaign against Ptolemy in Cyprus. Antigonus responded by targeting Rhodian shipping and claiming to have been attacked when the Rhodian navy responded. This was enough for Antigonus to order Demetrius to the island.

Rhodes was a significant force in the Aegean, with a united island, territory on the mainland, and a large fleet. However, this was no match for the forces Alexander’s successors could deploy. The largest known Rhodian fleet consisted of only 75 warships (Berthold, 1984, 42). In comparison, Demetrius sailed to Rhodes with over 200 ships. The number of available troops to defend Rhodes is estimated at around 7,000, compared to Demetrius’ army of 40,000.

It’s no surprise then that the Rhodians did everything they could to avoid this war. They had not shown any hostility to the Antigonids, they had merely refused to jeopardize their vital relationship with Ptolemy. Even when Demetrius arrived, they were willing to hand over hostages and ally with Antigonus. However, they refused to allow Demetrius access to Rhodes’ harbors. Once in the city, Demetrius would be able to exert control over Rhodes. A similar move had already given him control of Athens. The Rhodians were willing to compromise with Demetrius but could not simply surrender control of the city to him. They did not want it, but war was the only option.

Assault on the Harbors

The Rhodians prepared their defense the best they could. Inside the city, freedom was offered to slaves willing to fight, and resident foreigners not willing to join the defense were expelled. All the willing armed. They sent out a few of their fastest ships to raid Demetrius’ supply lines. Calls for aid were sent out to the Antigonids’ rivals.

When Demetrius arrived in the summer of 305 BCE, his forces must have seemed overwhelming. Not only did he bring his 40,000 troops and 200 ships, but a host of pirate vessels descended on Rhodes, hoping to plunder the rich island. But the Rhodian position was not hopeless. The city of Rhodes sits on a peninsula on the very northern tip of the island and was well fortified by its hills, giving it the appearance of a theater (Diodorus 20.83.2). On the eastern side sat five harbors, vital to Rhodian commerce and the city’s lifeline to the outside world. It was these harbors that Demetrius targeted first.

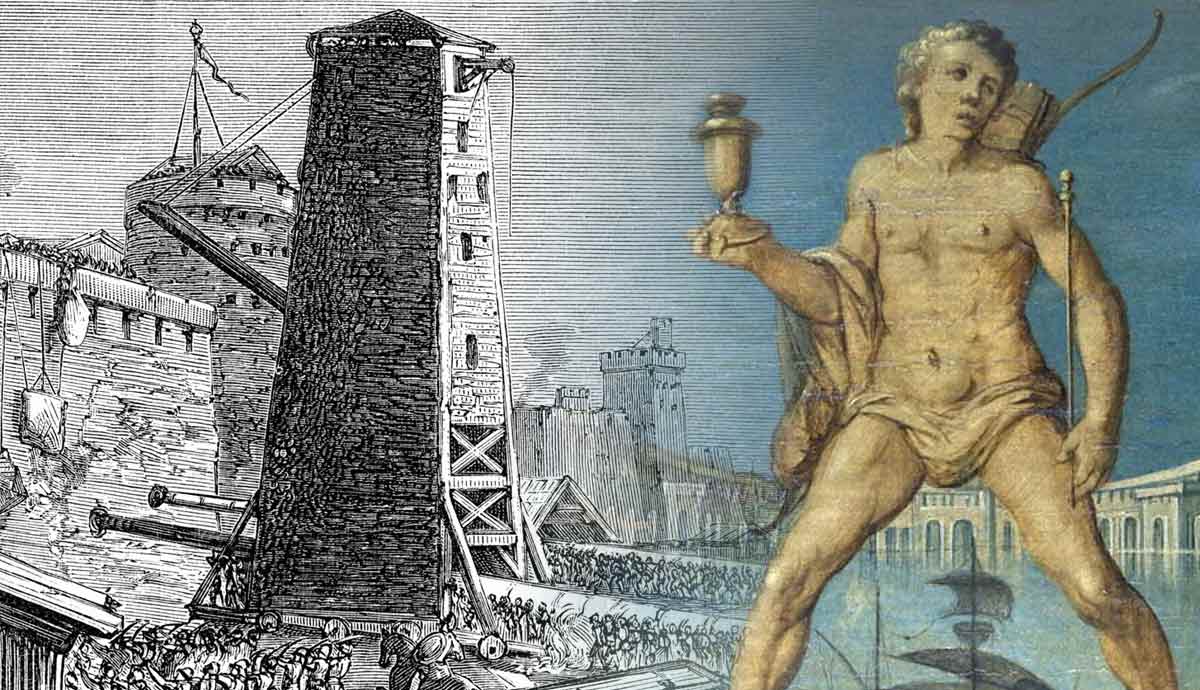

Both sides deployed a varied and innovative range of siege engines and artillery during the battle for the harbors and the siege as a whole. Demetrius loaded his ships with catapults and ballistae to bombard the defenders with rocks and bolts. In addition, massive siege towers were constructed on ships fastened together to tower over the harbor defenses. The Rhodians reacted by installing machines on the harbor defenses and on merchant ships floating in the harbor.

For eight days Demetrius assaulted the harbors from the sea. His siege engines battered the defenses and cleared the way for assault troops to try and storm the walls. But, the Rhodians held on, and a number of Demetrius’ ships ran aground in the unfamiliar waters. After a week’s pause to refit, Demetrius ordered another attack. Once again, hard pressed, the Rhodians manned a small number of ships and successfully attacked Demetrius’ floating siege engines. Undeterred, Demetrius simply ordered more and larger machines to be built, but bad weather intervened. The new siege machines were put out of action while the Rhodians used the opportunity to overwhelm Demetrius’ troops who had taken part of the harbor.

The assaults on the harbors had failed in part due to the difficulty of the operation and in part due to the resistance of the defenders. This first victory for the Rhodians was crucial. By keeping their harbors open, they allowed reinforcements and supplies to reach them. Around 150 soldiers from Knossos in Crete and 500 from Ptolemy soon arrived. These were not significant forces in themselves, but they showed that Rhodes had friends who now believed there was a chance they could win.

The Fight Moves to the Land Walls

As 305 became 304 BCE, Demetrius focused his attention on the land walls. The centerpiece of Demetrius’ new plan was the helepolis, a siege tower of such unprecedented size and sophistication that it became legendary. Modern estimates suggest the tower was 44 meters high, packed with siege engines, protected by iron plates and pulled along by 3,400 men (Wheatley & Dunn, 2020, 192). In addition, massive battering rams operated by 1,000 men flanked the helepolis. An incredible 30,000 men were required to build and deploy the machines (Diodorus 20.91.8).

Watching these efforts, the Rhodians must have been terrified. But wisely, they kept their heads. New lines of fortifications were prepared behind the now vulnerable walls. More raiders sailed out of the harbors and harassed Demetrius’ navy and supply lines. The Rhodians cleverly maintained the upper hand in the propaganda battle. The Rhodian assembly rejected a proposal to tear down the statues of Antigonus and Demetrius in the city. It was an act of restraint to demonstrate to the world that, even now, they held no ill will against the kings and that the aggression was coming from the other side.

Following a brief pause for an unsuccessful attempt at mediation, Demetrius’ machines started breaking down the fortifications. With their defenses crumbling, the Rhodians decided to launch a nighttime raid. They rained hundreds of flammable missiles and catapult shots at the helepolis, dislodging some iron plates and starting fires. Before it went up in flames, Demetrius pulled back the machine. The number of missiles the Rhodians were able to aim at the helepolis apparently shocked Demetrius, but he once again repaired the damage and pressed on (Diodorus 20.97). There are different stories about the ultimate fate of the helepolis. Our main account in Diodorus Siculus does not mention the destruction of the machine. However, a later story tells us the Rhodians managed to disable it by diverting water and sewage in front of the walls to bog it down in a mass of mud (Vitruvius 10.16).

As the battering rams did their job, more of the walls fell, but the Rhodians fought heroically on top of the rubble. A vital reinforcement of 1,500 Ptolemaic soldiers arrived, along with much-needed food, but the situation was now desperate. The defenses were breached, and Demetrius was proving as determined to take the city as the Rhodians were to hold it. After another attempt at mediation from several Greek cities failed, the siege moved into its crisis point.

Demetrius’ Final Assault on Rhodes

Demetrius had so far used sheer brute force to batter through the defenses of Rhodes. His next move was more subtle. He picked 1,500 men to silently climb through one of the breaches during the night, while Demetrius ordered the rest of his forces to distract the defenders by attacking at multiple points. The maneuver worked. Demetrius now had men inside the city holding sections of it while the Rhodians seemed confused. Fearing the city had fallen, there was every chance resistance would collapse.

But once again, the Rhodians held their nerve. Their elected generals ordered the defenders to stay at their posts on the walls while the newly arrived Ptolemaic troops were brought up to counter attack against Demetrius’ men inside the city. As dawn broke, the battle hung in the balance. In the fiercest fighting around the theater, commanders on both sides fell. Eventually, with the Rhodian defenders not collapsing, Demetrius’ men in the city were isolated and defeated. Having come close to falling, Rhodes still held.

Despite this defeat, Demetrius continued to prepare fresh assaults. By now, well into the summer of 304 BCE, the siege had lasted almost a year and Antigonus decided enough was enough. He ordered Demetrius to come to terms with the Rhodians. At the same time, Ptolemy advised the Rhodians to accept the best terms they could get. Antigonus was likely worried that the siege was taking too long and that the sympathy gathered by the Rhodians was not helping his cause (Berthold, 1984, 79). Ptolemy’s intervention is also interesting. His aid had been vital to Rhodes, but he acknowledged that the city could not hold much longer.

With both sides now willing to come to an agreement, Aitolian envoys negotiated a settlement. The Rhodians would have to surrender hostages and ally with Antigonus, though they were exempt from fighting Ptolemy. In return, Demetrius would not garrison Rhodes nor take tribute. After a year of hardship and battle, the settlement was little different from the positions at the start of the siege. However, the Rhodians had guaranteed that Demetrius would not simply take over their island. Their determination had protected their autonomy.

Legacy of the Siege of Rhodes

The siege was a defining event for both sides. In the aftermath, the Rhodians buried their dead, honored their heroes, and rebuilt their city. To commemorate their salvation, they erected a massive statue of the sun god Helios in the harbor, the scene of some of the fiercest fighting. So impressive was this Colossus of Rhodes that it became known as one of the Seven Wonders of the World and is still recognizable as a symbol of the island, even though it long ago disappeared.

For Demetrius, the siege gave him the nickname he is still known by: Poliorcetes (the Besieger). Historians have wondered whether the name was meant ironically, pointing out that he besieged but did not take Rhodes (Zielinski, 2023, 122). Demetrius’ conduct of the siege can be criticized. In particular, his failure to effectively blockade the island and close the harbors meant the siege was never complete. Furthermore, while impressive, his siege engines failed to overawe the Rhodians, whose use of artillery often countered Demetrius’ efforts. However, Demetrius’ campaign, in particular the variety and scale of the siege engines deployed, do seem to have been a genuine source of wonder in the ancient world. There can also be little doubt that the city would have fallen in the end. While he did suffer a number of reverses in his career, Demetrius was a skilled military commander and few other cities withstood the besieger.

Selected Bibliography

Berthold, R. (1984) Rhodes in the Hellenistic Age, Cornell University Press.

Errington, R.M. (2008) A History of the Hellenistic World: 323 – 30 BC, John Wiley & Sons.

Pimouguet-Pedarros, I. (2003) “Le siège de Rhodes par Démétrios et “l’apogée” de la poliorcétique grecque,” Revue des Études Anciennes 105, n°2, pp. 371-392.

Whealey, P. and Dunn, C. (2020) Demetrius the Besieger, Oxford University Press

Zielinski, T. (2023) “Demetrius Poliorcetes’ nickname and the origins of the hostile tradition concerning his besieging skills,” Ancient History Bulletin, 37.3-4, pp 120-141.