The Council of Ephesus was the third of the seven ecumenical church councils held within the first few hundred years of the Christian Church that worked toward determining the orthodox view of Jesus Christ as being both fully God and fully man.

Before the Council of Ephesus

In the previous two councils, the Council of Nicaea and the First Council of Constantinople, issues regarding extreme views as to the nature of Jesus Christ were somewhat resolved. At Nicaea in 325 CE, the heresy of Arianism – the belief that Jesus was created – was condemned; and at Constantinople in 381 CE the issue that Jesus did not have a human spirit – Apollinarianism – was condemned. However, particularly in the eastern church, a complete doctrine of the nature of Jesus was not fully resolved.

A priest from Constantinople named Nestorius was uncomfortable with describing Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ, as theotokos, meaning “God-bearer.” His preferred position on calling her Christotokos – “Christ-Bearer” – was causing controversy due to his theological position behind the term.

Nestorianism

Nestorius’ view, which has come to be called Nestorianism, held that there was a larger distinction between the two natures of Jesus Christ. In a letter to Cyril of Alexandria he wrote:

“Holy scripture, wherever it recalls the Lord’s economy, speaks of the birth and suffering not of the godhead but of the humanity of Christ, so that the holy virgin is more accurately termed mother of Christ than mother of God.”

What Nestorianism is a form of denial of the hypostatic union of Jesus – that He was fully God and fully man, both natures in one person. While it does not deny neither Jesus’ full deity nor His full humanity, it maintains a division between the two, so much that Nestorius believed that while Mary gave birth to Christ, she did not give birth to God.

Events at the Council of Ephesus

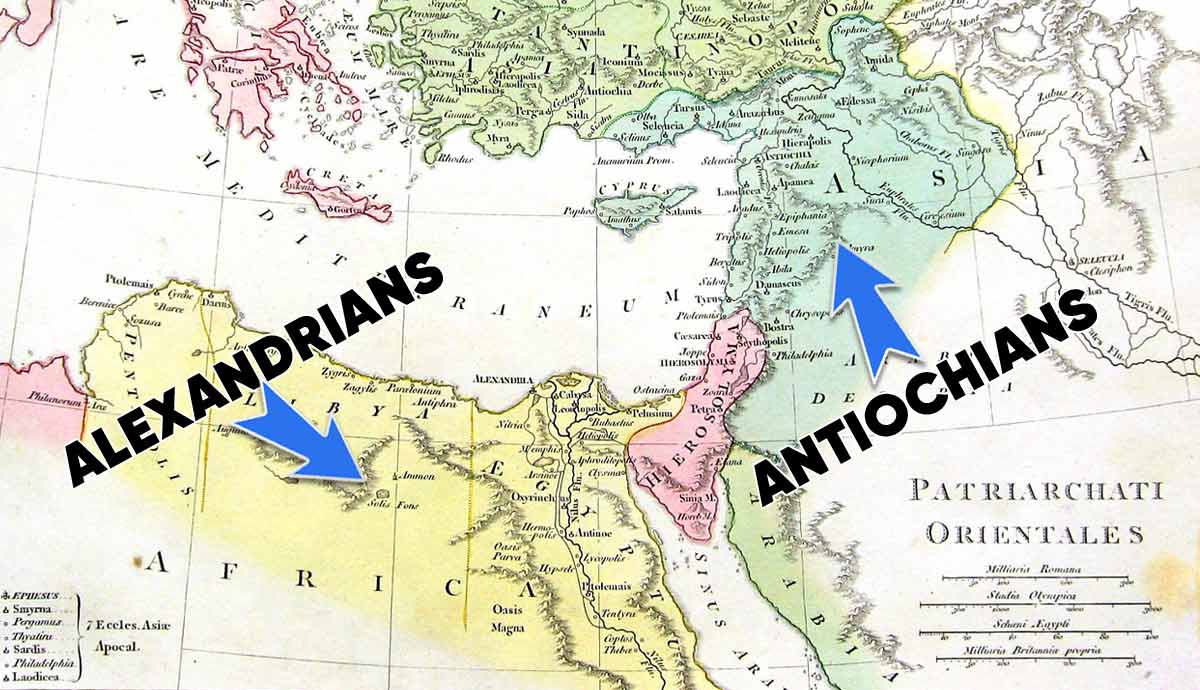

In 431, Nestorius requested that the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II convene a council to settle the issue, particularly because he though that he would prevail over Cyril, his main opponent. About 250 bishops attended, but a certain amount of political wrangling occurred. Cyril opened the meeting early, before many of Nestorius’ supporters could arrive. His ally, Patriarch John of Antioch, called an opposing council, condemning Cyril. Theodosius II sided with the decisions of Cyril and received the approval of Pope Celestine I. Nestorius and his followers were condemned, and the rift between the Western Catholic Church and the eastern churches was widened.

The Council of Ephesus also confirmed the Nicaean Creed of 325, and condemned any opinion contrary to it. Nestorius, seeing that he could not prevail, retired to his monastery, and was later exiled to Egypt.

Results of the Council of Ephesus

The Council of Ephesus’ decision to condemn Nestorianism led to the usage of extremely precise terminology in describing the nature of Jesus Christ. The concept of the Hypostatic union, which holds that Jesus Christ is both fully God and fully man together in one person, not two was further refined. This refinement has generally held even through the Protestant Reformation and is held as the orthodox position by all Christian faiths to the degree that it is, along with the doctrine of the Trinity, the standard on which any Christian group can be judged to be orthodox.

The other result of the Council of Ephesus was the splitting off of various smaller sections of the Eastern Church from under the authority of the West, and because of the political maneuverings, was one of the first steps which led to the eventual Great Schism between the east and west churches.