Today, when one thinks of the origin of sports and athletic competitions, the ancient Greeks often come to mind. Although many popular modern sports were inherited from the Greeks and Romans, the Greeks and Romans were influenced by earlier cultures. An examination of textual, archaeological, and art historical evidence shows that the ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Minoans, and Mycenaeans all enjoyed sports and athletic competitions. Despite many of these pre-Greek sports being quite different from what the Greeks practiced, others are similar and probably influenced the Greek ideals of athleticism, competition, and physical fitness.

Athletic Egyptians

The ancient Egyptians are best remembered for their pyramids, temples, tombs, and mummies, but they also had a very active sporting culture. Most of the evidence from Egypt comes from the temples and tombs, where sporting events are depicted in pictorial reliefs. There are also extant texts that describe different events, especially big game hunts.

Due to the nature of the surviving evidence, what we know about ancient Egyptian sports is primarily in the context of the elites. Little is known about the sporting culture of the vast majority of the population. Nevertheless, the primary source evidence shows that the Egyptians engaged in running, wrestling, hunting, and archery.

The best documented Egyptian running event took place during a king’s royal jubilee, known in Egyptian as the Sed festival. The event marked 30 years of a king’s rule and was celebrated by the pharaoh completing a run or jog around the circuit of a pyramid or temple complex. The earliest depiction of a potential Sed festival run is a jar label, dated to the rule of the First Dynasty king, Den (reigned c. 2900 BCE). The upper right register shows what appears to be the king running.

The first fully documented run was done by King Djoser (ruled c. 2667-2648 BCE) during the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Sed festival runs were not open to the general public and were not competitions in the modern sense. The king likely took as long as he needed to complete the run, and only members of the nobility and high priests would have attended.

Wrestling and combat sports were also performed in ancient Egypt, as demonstrated by two notable artistic examples. The best known is a collection of over 200 painted scenes of male wrestlers and female acrobats in the tomb of the official Baqet in Beni Hasan. The tomb is dated to about 2000 BCE and is significant for the number of male wrestlers.

A relief from the New Kingdom tomb of the noble Kheruef depicts men wrestling and stick fighting. Finally, carvings from the New Kingdom temple of Medinet Habu also depict wrestlers defeating foreigners in the presence of the pharaoh.

All of the Egyptian examples of wrestling and combat sports depict the contestants in loincloths with no audience or only the king in attendance. Many scholars believe that the purpose of Egyptian wrestling and combat sports was for military preparedness more so than the thrill of competition.

Physical Pharaohs

Perhaps the best examples of ancient Egyptian sporting culture were exemplified by the kings themselves. Egyptian theology held that kings were living gods, so they were also depicted as virile and strong in texts and art. In addition to the Sed Festival run, pharaohs were hunters, warriors, charioteers, and archers. Beginning in the New Kingdom (c. 1550 BCE), Egyptian kings also led their troops into battle on chariots, so they needed to be physically fit.

The 18th Dynasty king Amenhotep II (ruled c. 1427-1400 BCE) commissioned a stela to be created and installed near the Great Sphinx. The Great Sphinx Stela, as it is now known, gives an important glimpse into the sporting and active life of the pharaohs, as it describes how the king practiced archery.

“Entering his northern garden, he found erected for him four targets of Asiatic copper, of one palm in thickness, with a distance of twenty cubits between one post and the next. Then his majesty appeared on the chariot like Mont in his might. He drew his bow while holding four arrows together in his fist. Thus he rode northward shooting at them, like Mont in his panoply, each arrow coming out at the back of its target while he attacked the next post.”

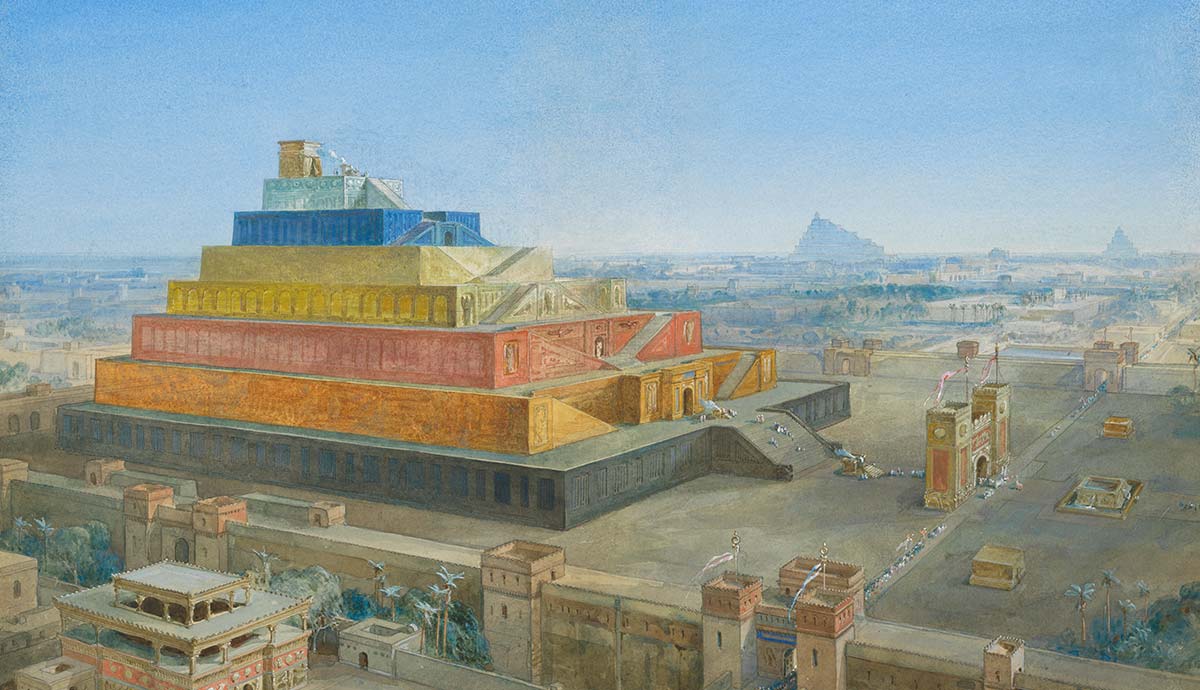

Exercise in Ancient Mesopotamia

Texts and art from ancient Mesopotamia reveal that the people who lived between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers enjoyed similar sports as their Egyptian contemporaries. Reliefs, seals, and other artwork show that combat sports, particularly wrestling and boxing, were popular. One of the best preserved artistic examples is a relief on a plaque depicting two boxers. The boxers prominently wear kilts, unlike the Greeks, who later competed in the nude.

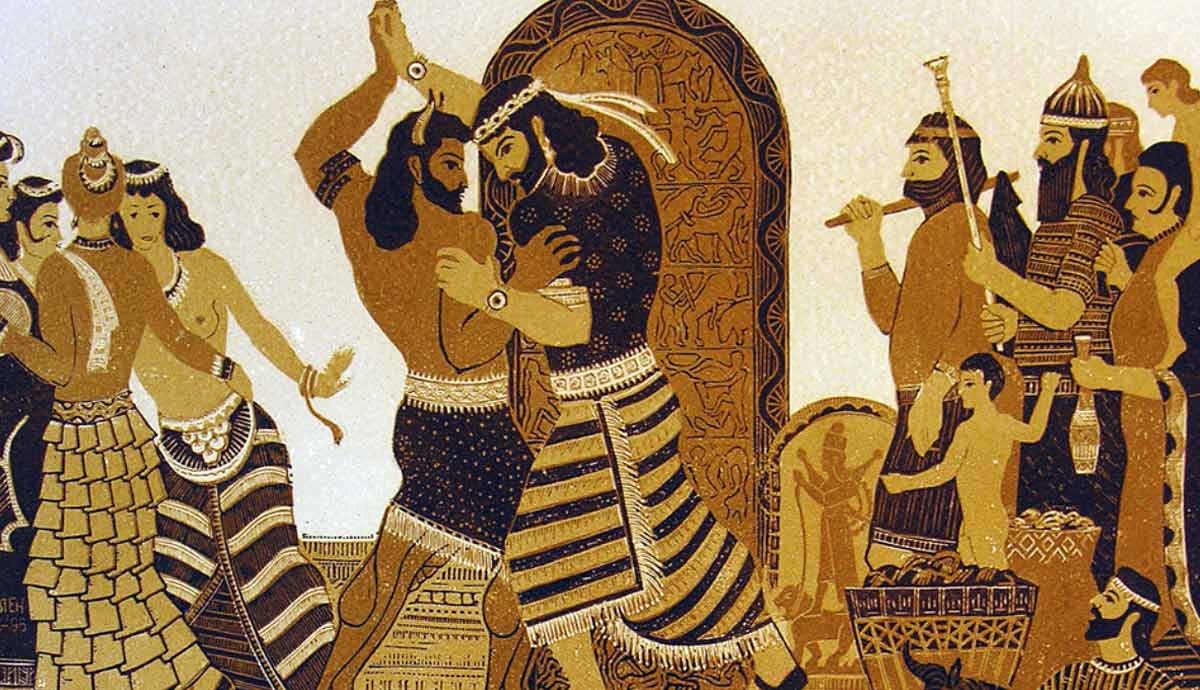

Wrestling was also depicted in Mesopotamian texts, with the most notable example being in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. The epic is the story of the adventures of a legendary king of Uruk named Gilgamesh and his divine traveling companion, Enkidu. When the two characters first meet, Enkidu challenges Gilgamesh to a wrestling match.

“Mighty Gilgamesh came on and Enkidu met him at the gate. He put out his foot and prevented Gilgamesh from entering the house, so they grappled, holding each other like bulls. They brook the doorposts and the walls shook, they snorted like bulls locked together. They shattered the doorposts and the walls shook. Gilgamesh bent his knee with his foot planted on the ground and with a turn Enkidu was thrown.”

Mesopotamian Royal Virility

Like their contemporaries in Egypt, Mesopotamian kings also engaged in different athletic exercises to prove they were worthy of the office. Many Mesopotamian kings were documented to have performed physical feats that included trials of strength and endurance. In the Sumerian text known as the Hymn of Shulgi, the Ur III Dynasty King Shulgi (ruled c. 2094-2047 BCE) claimed to have engaged in a round trip run from the Temple of Ur to the Temple of Nippur and back for a total of about 100 miles. The most incredible part of the text is that the king claimed to have run the circuit in one day: “As in one (and the same) day I celebrated the eshesh-feasts in (both) Ur and Nippur.”

The Assyrian kings also shared a common athletic pastime with their Egyptian contemporaries: royal hunts. It is unknown when Assyrian kings began engaging in royal hunts, but one of the earliest known documented instances comes from the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I (ruled c. 1114-1076 BCE). The text describes how the king hunted bulls and elephants and even brought some of the elephants alive with him back to the capital city of Assur.

“At the bidding of Urta, who loves me, four wild bulls (aurochs), which were mighty and of monstrous size, in the desert, in the country of Mitani, and near to the city of Araziki, which is over against the land of Hatti, with my mighty bow, with my iron spear, and with my sharp darts, I killed. Their hides and their horns I brought unto my city Assur. Ten mighty bull-elephants I slew in the country of Harran, and in the district of the river Habur. Four elephants I caught alive. Their hides and their tusks, together with the live elephants, I brought unto my city Assur.”

Reliefs from the Neo-Assyrian Dynasty (c. 911-609 BCE) show that the Assyrian kings continued the practice of royal hunts but focused most of their attention on lions. Reliefs from Assur and other cities, now in the British Museum, show that most of the hunts were done from chariots. But the later Assyrian King Ashurbanipal (ruled 668-627 BCE) claimed to have hunted lions on foot with a lance or mace. The pictorial and textual evidence indicates that Neo-Assyrian lion hunts were staged and done for spectators, centuries before the Romans hosted similar events.

Did the Mycenaeans Have a Sporting Culture?

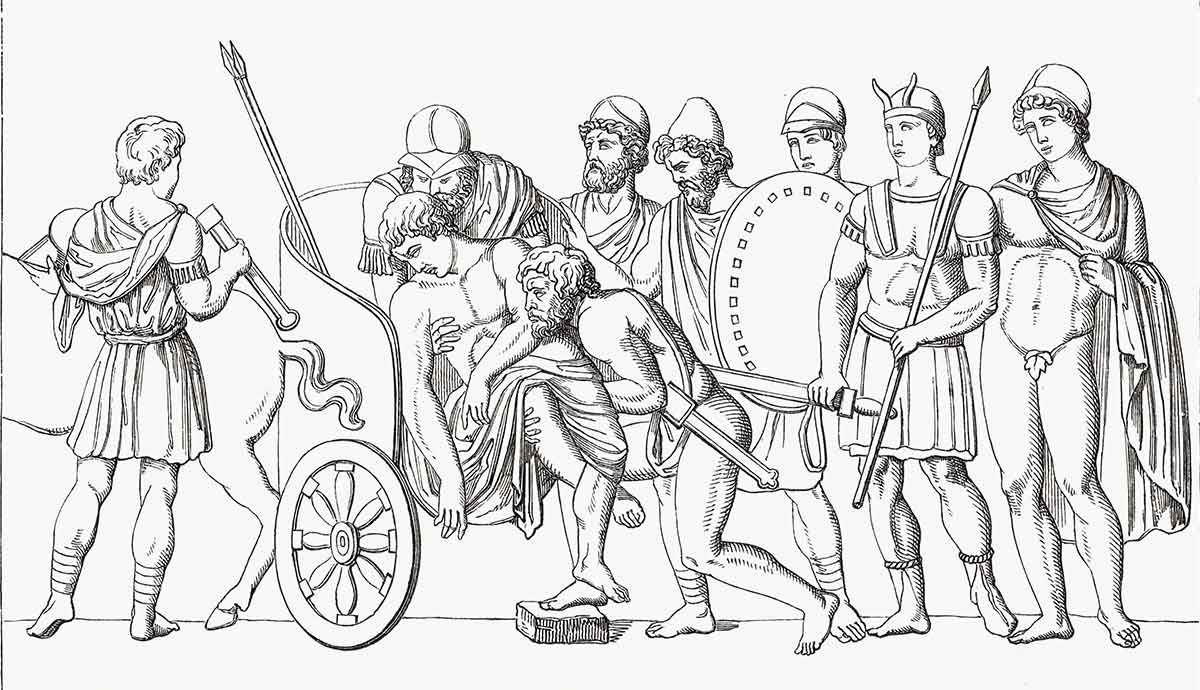

The above question would seem strange to many because the Mycenaeans were the direct ancestors of the classical Greeks. The classical Greeks inherited their language from the Mycenaeans, and it makes sense that they would also have inherited some of their sporting traditions. However, there are no Linear B texts that mention athletic competitions or exercises, and there is also very little archaeological or historical art evidence. Still, it is known that the Mycenaeans rode chariots. It is logical to assume they engaged in chariot races. There is also the matter of the funeral games in The Iliad.

Although Homer detailed a number of funerary games in The Iliad, it is important to remember that Homer lived in the 8th century. It is very possible that Homer anachronistically attributed athletic competitions of his own era to the Mycenaeans and Achaeans of the late 13th to early 12th centuries. That said, one piece of evidence from Cyprus suggests a Mycenaean sporting tradition.

The piece in question is a krater from Cyprus, now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, dated to between 1350 and 1250 BCE. The location and time clearly make the piece Mycenaean, and the content suggests it is a depiction of multiple sporting events or games. The scene, which is shown on both sides, shows a chariot driven by two men before two men belt wrestling. The wrestlers invoke images of Near East wrestling competitions or possibly the much closer Minoan culture.

Wrestling, Boxing, and Bull Jumping on Ancient Crete

The ancient Minoans were clearly lovers of beauty, which can be seen in the wonderful frescoes in their magnificent palaces. The Minoans built their culture on the island of Crete, and though the classical Greeks were unrelated to them in terms of language and origins, it is clear that the latter inherited a love of beauty and sports from the former. An examination of the archaeological and art historical evidence reveals that the range of Minoan sports included boxing, wrestling, possibly pankration, and bull jumping.

The best-preserved evidence of Minoan combat sports is a vase from the site of Hagia Triada, now known as the Boxer Vase or Boxer Rhyton. The sporting events of boxing, wrestling, bull-leaping, and possibly pankration are depicted on four registers. The top register depicts two men boxing, while the fourth register shows one man who has been thrown to the ground in a wrestling move. The third register depicts four helmeted men with forearm guards and padded hands. Two of the men are upright, while two are on the ground in what appears to be a simulated combat event. The second register shows the very popular yet somewhat enigmatic Minoan sport of bull-leaping.

Modern historian Donald Kyle has argued that the vase could be read sequentially as different sporting events at a festival. Many of the events on the Boxer Rhyton were apparently adopted by the classical Greeks, although with some notable differences in details. Minoan athletes were always clothed, wearing codpieces, belts, and leg wrappings below the knees.

Hurdling Over Bulls

The best-known but least understood of all Minoan sports was bull leaping. There are several artistic depictions of this event on beautiful frescoes from Knossos. The sites of Zakro, Malia, and Phaistos also have art and archaeological evidence of bull leaping. The most famous of these is the so-called “Toreador Fresco” from the palace of Knossos. The Toreador Fresco depicts three approximately one-foot-high human figures leaping over a bull. The first leaper faces the bull, grabbing it by its horns, the second leaper does a handstand on the bull’s back, and the third leaper finishes on his feet by facing the rear of the bull. The three figures are clearly different men, but Kyle has suggested that they possibly show the three stages of a proper bull leap.

Archaeological work at Knossos and other sites has uncovered that bull-leaping events likely took place on the palace grounds. Some of the frescoes show a two-story structure, which likely meant that the spectators were located on the second floor. The central court area on the eastern side of the palace is the most likely place where bull-leaping events were held. There was also a compartment on the ground level that was large enough to temporarily hold the bulls for the events. Bull-leaping events probably had religious origins, but by the time the frescoes were made, they were a spectator sport for the elite.

The classical Greeks are known for their sporting culture and are often credited with being the inventors of many modern sports. An examination of the sources shows that the peoples of the ancient Near East and Aegean also had active and important sporting cultures. It is likely that those pre-Greek sporting cultures influenced the better known sporting culture of the classical Greeks.