The first chapter of the Siberian expansion began in the 1550s. Unlike America’s Old West, Imperial Russia partially sponsored the first attempts. In 1558, the Stroganov merchant family, backed by the Tsar, crossed the Ural Mountains, often seen as the European/Asian border. They built a series of trading posts, protected by Cossack mercenaries. This also meant fur traders, settlers, and priests followed later. And like America, the Indigenous nations faced upheaval and change.

This initial attempt ended in 1582. A Cossack army, led by Yermak Timofeyevich, defeated the Siberian Tatars. This success marked the push that only ended in the 19th century.

The Why of Going East

The principal reason came from the fur trade. Fur, especially sable, commanded higher prices than gold during the 16th and 17th centuries. Sables, a type of mink, became a major export. Native tribes paid tribute with sable fur filling Imperial coffers. Siberia also meant security with space, a constant theme in Russian history. A continual drive east pushed potential enemies further out.

Though fur provided the economic engine, this colonizing effort still carried Imperial prestige. The expansion made Russia look like a civilizing force. The control too over such a large area put Imperial Russia on par with the Ottomans and Habsburgs.

Russia’s Indigenous Opposition

Siberia’s Indigenous tribes fiercely resisted Russia’s Siberian push. The Yakuts (Northern Siberia) fought bitter battles between 1634 and 1642. The Evenki people around Lake Baikal fought but were defeated by the Cossacks. Even after an initial defeat, tribal resistance could last decades. Some tribes adjusted, but others fled.

The Evenki migrated to places such as Sakhalin Island and Mongolia. Like most Indigenous populations, outside diseases, Cossack massacres, and forced relocations decimated the tribes.

Beyond the Urals: 1580-1689

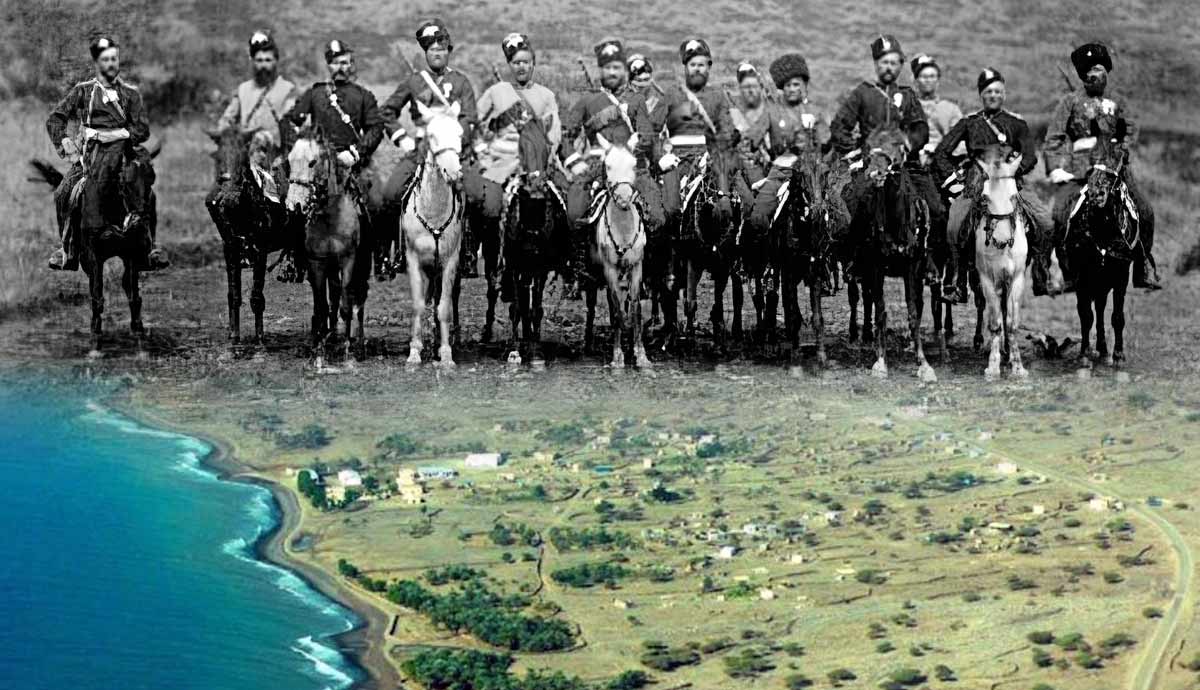

With initial resistance crushed, the Cossacks crossed the Urals. These tough, mobile semi-independent soldiers made their first inroads. Using Siberia’s major rivers for rapid movements. Rivers like the Yenisei led them to central Siberia; the Ob opened western Siberia, and the Lena led to the far northeast. The Cossacks did more than merely pass through.

On their journeys, they established ostrogs (forts) and mapped the territories. The Cossacks founded important fort-towns like Tyumen (1586), Tobolsk (1587), and Tomsk (1604). Each was built on or near river junctions, enabling rapid movement and communication. The Cossacks established an annual fur tribute, or yanak. To collect such tribute, coercion and hostage taking became the norm. The Cossack reacted violently against resistance, often killing many.

The Cossacks crossed the breadth of Siberia. The first group reached the Pacific at the Sea of

Okhotsk by 1639.

The Second Wave

The Cossacks created a path across Siberia, touching many places. It would be the second wave to fill out that space between the Volga and the Pacific. Like America’s western expansion, Russia’s Siberian moves occurred haphazardly. As this wave moved in, each with separate intentions, they slowly integrated Siberia into Russia.

The groups that came east consisted of merchants, promyshlenniki (trappers and explorers), soldiers, exiles, settlers, and clergy. The merchants followed the Cossacks, hoping to profit by supplying frontier forts or establishing trading posts. Their activities created infrastructure and fund expansion. Imperial soldiers arrived too, often to enforce government control or fight uprisings. The clergy followed established routes, often invited by locals. Besides building churches, the clergy converted local tribes, expanded Orthodox influence, and shaped the culture.

For Russia’s downtrodden serfs, Siberia meant freedom. Once over the Urals, Siberia’s vast expanse offered anonymity. Few landowners had the means to hunt them down. Additionally, frontiers always needed extra hands, bare backs, and bosses asked few questions.

Integration, China, and Establishment

After 1700, each succeeding decade pulled Siberia closer to Russia. Upon reaching the Pacific coast in 1639, efforts turned southward or toward consolidation. Imperial Russia and Qing China signed the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk, after repeated clashes, creating an official border. This lessened tension as both moved into the Amur region. The last Indigenous uprisings occurred in the late 1700s, such as the Chukchi.

Siberia gradually became Russia’s economic engine. After 1700, important towns like Irkutsk, Tobolsk, and Yakutsk gained prominence. Mining began in the early 1700s, including silver mines near Lake Baikal. Iron, copper, or lead mines were established in the Altai Mountains. The 1838 gold discovery in the Yenisey River basin created Siberia’s first gold rush.

Siberia’s 19th-century history included greater industrialization and the exile of political or religious opponents. Great cities like Vladivostok were founded in 1860, and the borders were finalized. Siberia proved economically crucial to the Soviets and modern Russia. But Siberia’s frontier era set the tone.