Aristotle (384 BCE to 322 BCE) was an ancient Greek philosopher and scientist who was considered to be an all-around genius. Today, he is regarded as one of the most influential thinkers in Western history. His ideas about logic, how the world works, right and wrong, and government basically influenced how people would think for centuries. While many people know him from literature, there are a lot of surprising things about his life and work that many don’t know. Beyond the old statues and books, he was a curious man with a life full of unexpected turns.

He Taught Alexander the Great

While Aristotle’s ideas are what he’s most known for, he also taught Alexander the Great. In 343 BCE, King Philip II of Macedon asked Aristotle to be the personal teacher for his then 13-year-old son, Alexander. His help was then seen as key in making the future winner. Aristotle spent about three years at the Macedonian court teaching Alexander many things that included right and wrong, how to rule and even health. He is said to have given Alexander a marked copy of Homer’s Iliad which Alexander took with him through all his fights.

The effect of the teaching is debated among history experts, but it’s clear that Aristotle instilled a strong sense of love for Greek ways and learning in Alexander. While Alexander later went on a path of conquest that was very different from Aristotle’s more calm ruling ideas, the close link between a wise teacher and a future world leader shows Aristotle’s real work influencing some of the most powerful people of his time.

He Studied Animals and Nature

Many people picture Aristotle as a man whose thoughts dwelt only on deep abstract ideas such as the soul or the value of life. But much of his work also concerned the natural world, often studying their characteristics and anatomy.

During his life, he provided research reports on over 500 species of animals. The works included the History of Animals, Generation of Animals, and Parts of Animals. They ranged from small insects and sea crabs to fish, birds, and large mammals. Some of his notes on life in the sea, especially near the island of Lesbos, were very accurate. They showed a strong grasp of how sea creatures lived. For example, he correctly found that whales and dolphins had the characteristics of land animals (mammals). He deduced that they breathed air and gave birth to live young – a fact not fully known until many years later.

His Lost Works Are Still Fascinating

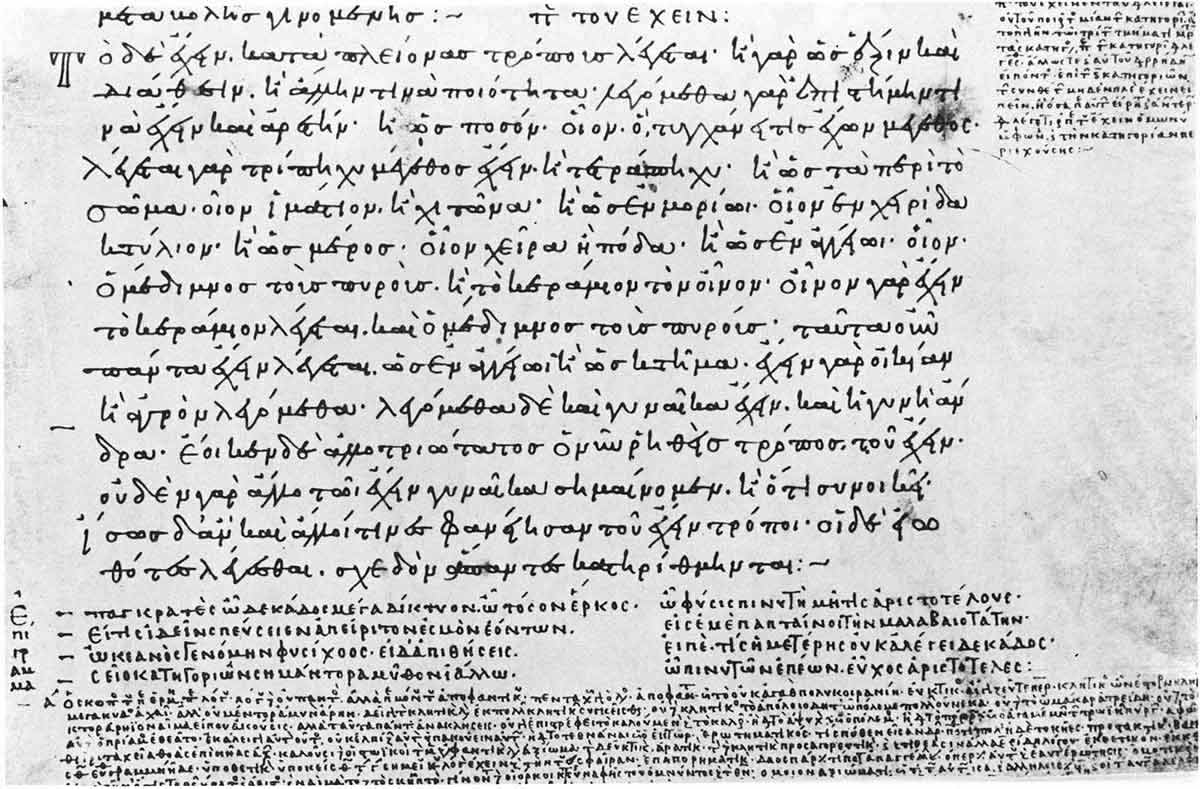

Aristotle’s remaining writings are vast. However, they are only a small part of what he actually wrote. Old records show that Aristotle made hundreds of works. His contributions laid the foundational stones in fields such as metaphysics, ethics, and natural sciences, among others. The writings he planned to share with the public were well-known and praised in ancient times for their exceptional knowledge. Sadly, most of them are gone and exist only as quotes copied by later writers.

The writings we have today are mostly his study notes and detailed papers meant for his students at the Lyceum. Notably, they were not meant for everyone to read and are often packed with ideas and challenging to understand. The loss of such a significant portion of his ideas can be considered a significant loss of information to people who have been inspired by his legacy.

He Started One of the First Major Study Institutions in Athens

After teaching Alexander, Aristotle went back to Athens and in 335 BCE, started his own school called the Lyceum. Its name came from the Greek Lykeion, named after the temple of Apollo Lyceus. While Plato’s Academy focused a lot on math and deep ideas, Aristotle’s Lyceum had a wider, more hands-on and organized way of learning. Many people see it as one of the first major institutions for studies in Athens. At the institution, students and researchers did study projects in areas such as life science, past events, government, public speaking, and how things work.

His Writings Led to the Sharing of Ideas With the Muslim World

While Aristotle’s writings were mostly lost to Western Europe after the Roman Empire fell, they were saved, read, and discussed by scholars from Byzantium and Muslim regions. During the Muslim Golden Age (8th to 13th centuries), Arab thinkers like Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, Avicenna and Averroes put Aristotle’s ideas about thinking, deep truths and nature into their own language and added to them.

It was through Arabic copies and discussions that Aristotle’s writings came back to Western Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries. Their rediscovery triggered a major change in medieval schooling.