Paint marks, scratches, or incised markings on surfaces or objects may not look like a form of writing at first glance. In fact, many were overlooked when first discovered until scholars started asking questions. Does it have a meaningful purpose? Is it art? Is it merely decoration? Is it writing? If, in addition, it represents an unknown language from a lost civilization, the recognition of an ancient script as writing needs a keen eye, a sharp mind, memory, and imagination to augment academic training.

Codebreakers

Two significant discoveries in the ancient Near East unlocked Egyptian hieroglyphics and cuneiform writing. These are the well-known Rosetta Stone and the Behistun Inscription of King Darius, respectively. Both discoveries had already been recognized as writing systems, but decoding them remained elusive until scholars realized that the marks on each represented trilingual inscriptions—repeating the same message in three languages. Unfortunately, this kind of lucky break remains a rarity in decoding.

The key to the identification of markings and glyphs as writing usually lies in finding enough examples that indicate a pattern or a deliberate formation of symbols. Deciphering an unknown language often progresses from a mere suspicion to a theory, and the appearance of enough samples. Today, this process may include multi-disciplinary investigations, various dating methods, comparisons, trials, errors, and more before the final “eureka” moment.

The complexity of the entire process, especially when the underlying language is unknown and samples are few, brings us to the complex reasons why there are scripts that have yet to be deciphered.

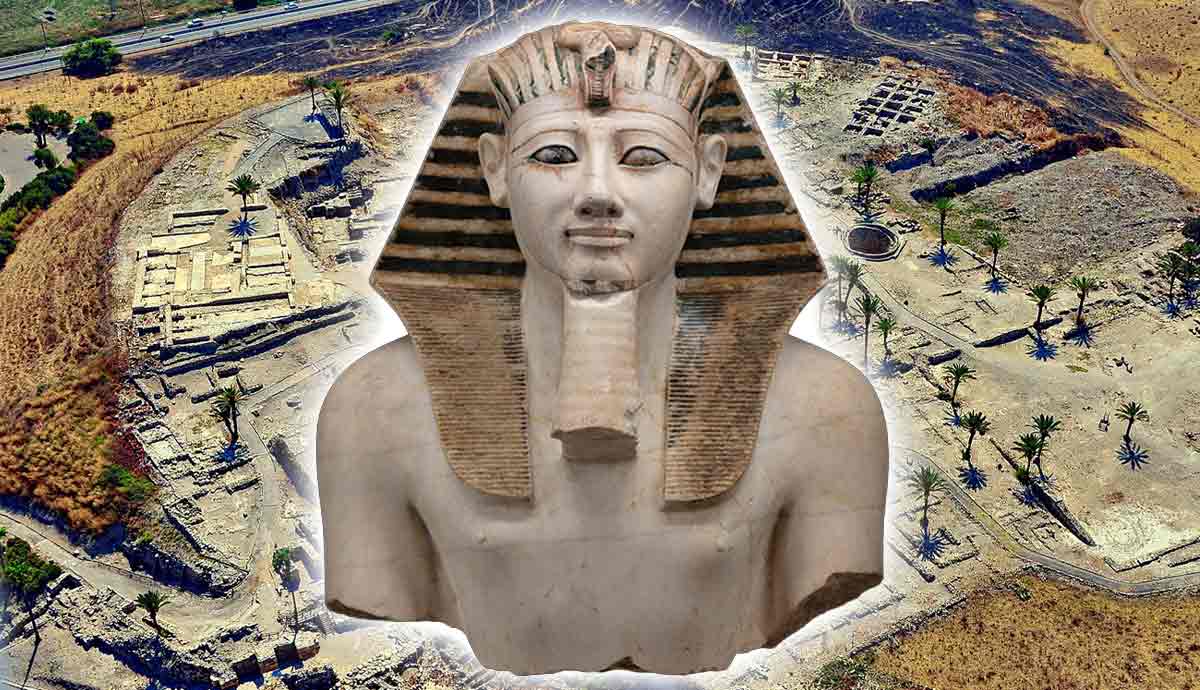

1. Linear A Script From Minoan Crete

British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans was excavating the magnificent palace of Knossos in 1900 CE on the Greek island of Crete. Every day brought exciting discoveries. Among the finds were fragments of clay tablets with an unknown script. Evans dated them to around 1800-1450 BCE based on the stratigraphy of the site. They were published by Oxford University Press, and so started the efforts of deciphering what Arthur Evans christened Linear A script.

Facts and Accepted Speculations

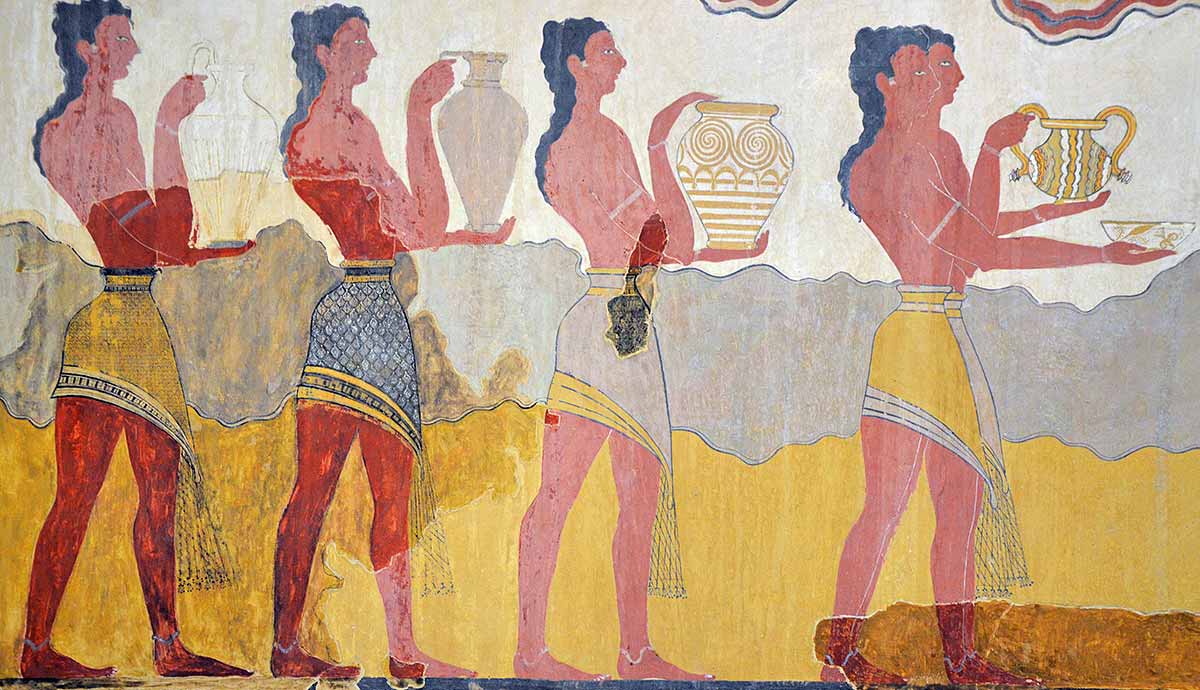

- The script was used by a lost civilization on the island of Crete. Evans named the people the Minoans after the legend of King Minos.

- It is the written representation of an unknown underlying language that bears no resemblance to any known language or writing system, except for a visual similarity to later Linear B script.

- Scholars generally agree that it is a combination of syllabic and full word signs (logograms). Some speculate that there could also be indications of phonetic and ideographic values assigned to some symbols.

- Extant inscriptions are on small rectangular clay tablets, pottery, metal objects, stone vessels, and seal impressions on clay objects. Painted graffiti on walls and pottery is poorly preserved. There are no remains of writing on perishable materials.

- About one-fifth of the symbols resemble a Cretan hieroglyphic script (also undeciphered) developed around 200 years earlier on the island.

- The two scripts were used simultaneously for a period, with Linear A centered in the central and southern parts, and Cretan hieroglyphs in the north and north-east of Crete.

- The main portion of the extant fragments of Linear A was discovered at Minoan palaces on Crete, like Phaistos and Knossos. Small numbers were also found on Santorini, several Aegean islands, mainland Greece, the Levant (Israel), and Anatolia, likely as marks on trade goods.

- Most of the recovered scripts contain very few symbols or signs.

- The longest inscription found to date (2024) is on an ivory scepter discovered in a cultic building at Knossos. Scholars speculate that it had both political and religious ceremonial purposes. It contains 119 logosyllabic signs and twelve framed depictions of animals.

- A few characters of the Linear A script look similar to the later Linear B script developed by the Mycenaeans after they came into contact with the Minoans. Linear B was deciphered in 1952 because of its underlying language similarities to known archaic and classical Greek.

- Linear A and Linear B represent two entirely different languages: Minoan and Mycenaean. Similarities, thus, are limited to appearance, but not meaning. Scholars agree that Linear B most likely evolved from Linear A.

- Decoding the undeciphered language by linking it to the origin of the Minoan people is impossible. DNA studies of ancient remains indicate that they were descendants of Neolithic European settlers, probably from ancient Anatolia via Europe to the Aegean. Their DNA is most closely related to the modern inhabitants of Crete.

Theories and Speculation

Linear A script was likely developed for trading purposes (quantities, contents, and ownership). Administrative lists of these details were made at ports of departure and maybe at ports of arrival. It is fairly certain that the use of the script expanded to include other administrative functions, record keeping, and religious texts such as hymns.

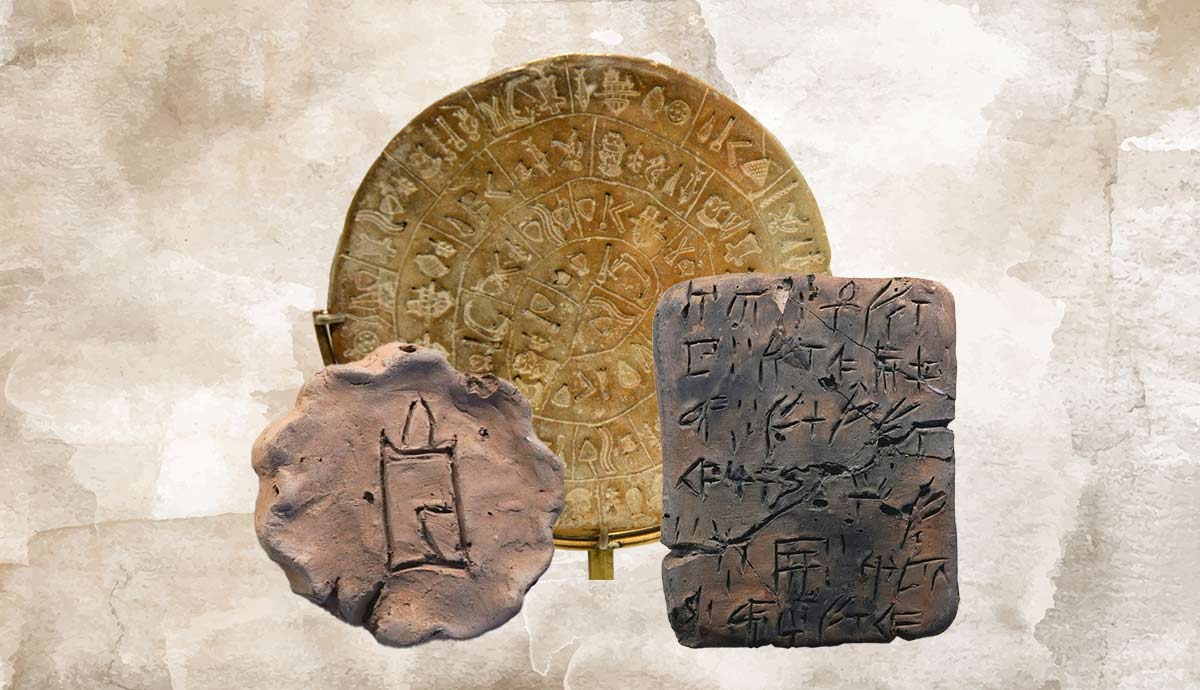

2. The Phaistos Disc

This fascinating fired-clay disc was recovered from the Minoan Phaistos Palace in 1908 by Italian archaeologist Luigi Pernier. It has been dated to the period of the Minoans, 1800-1450 BCE. 241 signs spiral in a row from rim to center across the surfaces on both sides of the six-inch (15.9 cm) diameter disc. A vertical line with dots on each side of the rim appears to indicate the start of the spiral and the direction of the impressions.

According to the Heraklion Archaeological Museum in Crete, sequences of signs are repeated up to 61 times. The uniform execution of the same symbols indicates that they were stamped into the wet clay rather than redrawn or written, tantalizingly indicating an early form of “typesetting.”

Theories of its purpose vary from a cult object to a game board or educational tool, or a religious text like a hymn or prayer, or even part of a musical instrument. The signs and symbols do not represent any known script, including Linear A, Linear B, or Cretan hieroglyphs, although there are a few similarities.

After more than a century, there are still ongoing debates about its authenticity, mainly because no similar imprint technique or identical script has ever been discovered. Despite several claims of full or partial decoding of the Phaistos disc, none of these have yet been accepted. Scholars are also divided about its origin, although there seems to be consensus that it was made somewhere in the Aegean, if not on Crete.

3. The Indus Valley Civilization Script

The undeciphered Indus Valley Civilization script was identified by a British civil servant and archaeologist, Sir Alexander Cunningham, who published a drawing of an inscribed, fired soapstone seal from the ruins of Harappa in 1875. The seal impression represents a striking image of a unicorn accompanied by a short inscription. It has become widely known as the Unicorn Seal.

Excavations at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro during the 1920s and later uncovered more samples, and the significance of the script became clear. Deciphering the script of this intriguing, advanced ancient civilization may unlock valuable information about their well-planned cities and political structure. It may also answer the baffling questions, such as the lack of palaces and temples amongst the ruins.

Unfortunately, the extant examples of the Indus Valley script are limited to short inscriptions consisting of only a few characters each. There are around 4,000 examples, of which the longest has a mere 34 characters. The extant inscriptions are limited to seals, pottery, and tiny tablets.

The subject of deciphering the script of the Indus Valley Civilization made headlines again in 2025. Tamil scholars claimed that they found definite similarities to ancient pottery inscriptions in the state of Tamil Nadu, India. This prompted their local government to offer a $1 million reward for the deciphering of the IVC script. The hope is that it would prove a link to the Dravidian language family, and ultimately Tamil.

4. Rongorongo

Most people know about the enormous and enigmatic stone sentinels of Rapa Nui—the Moai. Fewer know about Easter Island’s second mystery—its script that has yet to be deciphered! The Rongorongo script is believed to be a legacy of the first settlers of Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui, in the vast Southeastern Pacific Ocean. The settlement was thought to date back to around 400 CE. The latest radiocarbon dating, however, brought it forward to as late as 1200 CE.

Radiocarbon dating of a Rapa Nui wooden tablet with Rongorongo script, tested in Bologna during 2024, proved that the wood was centuries older than the first European contact with the islanders (1722 CE). The results thus indicate that the script was an indigenous invention without outside influence, contrary to previous beliefs that the writing developed through contact with Europeans.

The script was discovered by a novice priest of the Roman Catholic Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in Paris. Brother Eugène Eyraud was stationed on Rapa Nui in 1864. He mentioned in his reports that there were wooden tablets with strange symbols on them in every home. He did not elaborate, except that there were animal inscriptions of species not present on the island.

Later, investigators of Rongorongo learnt that, according to local oral tradition, the ancestors of the Rapa Nui brought 67 such tablets with them when they first settled the island. The knowledge of reading and writing the script was limited to scribes and elites who passed it on to only their direct descendants over the centuries. These settlers were Polynesian.

Scholars have established that the script is not related to any Polynesian or other known writing systems across the Pacific islands or Oceania. A few of the symbols are identical to glyphs in the thousands of petroglyphs recorded on Rapa Nui.

Although the islanders still spoke the same Polynesian dialect as their ancestors when the Rongorongo script was recognized as writing, they could not read the glyphs. It is postulated that the elite and the scribes who knew the writing had died out or fallen victim to the highly active slave trade (blackbirding) operating from Peru and Colombia across the Pacific. After the meaning of the writing was lost, the islanders used the tablets as firewood and boards to wrap their fishing lines around.

When the importance of the discovery was finally realized, there were only around 30 tablets with texts left! The characters are carved in parallel lines across wooden tablets, rods, and ornaments. Scholars have established that they were carved with obsidian sherds and shark teeth. They have identified nearly 600 glyphs representing humans, animals, plants, and abstract objects. They are fairly certain that the script must be read in reverse boustrophedon.

5. The Vinča Script

Perhaps the most intriguing ancient symbols that could be interpreted as writing are the Vinča script symbols, also known as Old European, dating back to more than 5000 BCE in the Neolithic Age. Hungarian archaeologist, Baroness Zsófia Torma, discovered artifacts covered with unknown abstract symbols at Turdas, Romania, in 1875.

A cache of similar symbols was unearthed in 1908 in Vinča, Serbia, which became the type-site. Later finds from the 1960s onwards were made across the Balkans, the Danube basin, and neighboring countries of Southeast Europe, including Greece.

The Vinča script contains geometric shapes, crosses, lines, waves, swirls, comb-like patterns, zoomorphic figures, stick humans, swastikas, and more. Scribes inscribed or painted them on wet clay tiles, pottery, figurines, and more. Like the other undeciphered scripts, it represents an unknown language, languages, or dialects.

The main controversy surrounding the script is whether it can be interpreted as the earliest form of actual writing, more than 1,000 years before cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs. Its long and widespread use and organization into repetitive patterns on several recovered objects, however, appear to confirm its use as a communication tool for both words and abstract concepts.