Often the idea of important historical cities makes us think of Rome, Athens, London, and other places of grand empires or royal dynasties. However, if we look further back the first real transformation on cities and civilization as we know it actually occurred in ancient Mesopotamian cities of Uruk and Ur.

Uruk: “The First City”

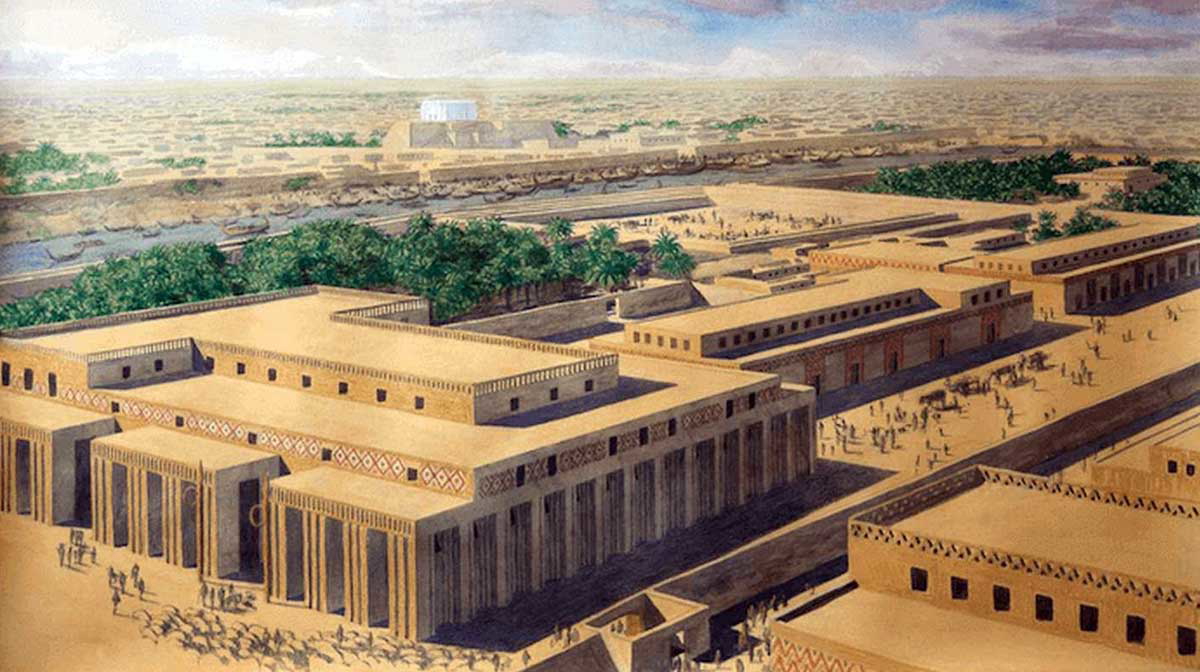

3200 BCE in the city of Uruk. All around are walls built with mud bricks, along with artisans, scribes and traders. This was the birth of “urban revolution,” a phrase used about the shift of rural “towns” to larger civic centers. It was the largest settlement in Mesopotamia of its time. The Early Uruk period of time began in 4000 BCE, after the Ubaid period where smaller communities were predominant.

One of the reason the Uruk became a city and successful is where it was located. The land in Southern Iraq at the time had been a marshland and now lent itself to agriculture. Like many settlements through history that sprung up from previously nomadic individuals or small societies the ability to grow food was essential.

Cities cannot survive without some form of government. With the formation of Uruk began the development of a civic system and economy. It is here that art thrived with carving on the wall first appearing here, a giant aqueduct which provided water for people and crops, and the pictographs which would become the precursor to cuneiform, the first written word.

Writing and Record-keeping in Uruk

Clay was abundant, cheap and durable. Soft clay could be marked with a stylus; drying or firing preserved the text. Once tablets became standard, layers of archives built up. Today there are many existing fragments that have been found in various archaeological sites that allow us to trace how the written word came to exist. At first the drawings, now known as pictographs, were relatively simple. They were based on objects or commodities and used in trade.

Over time, these tablet inscriptions became more complex: signs came to stand for actions and agents (not just goods), and the symbolic repertoire expanded. This expansion made it possible to record who did what, for whom, and with what product or resource. Thus, the record-keeping shifted from mere counting to detailed administration. It was from there that using sounds for words made it more than just a drawing of an object.

Uruk’s Canal and Ditch System

Uruk’s canal and ditch networks were important because they were the foundation for early urban life in southern Mesopotamia. The infrastructure reshaped settlement patterns across the Uruk lands. Today, surveys and palaeogeographical studies prove that the way the settlements were engineered used both landscaping and plots to support expansion in zones previously unfit for settlement. This connected the Euphrates River to support a larger growing population.

Managing the canals required sustained, coordinated effort. For Uruk this meant centralized planning, scheduling of canal maintenance and allocation of water, and institutions capable of marshaling people to work it. Canals also functioned as transportation routes. Boats moved goods and people more efficiently than overland routes, facilitating long-distance exchange during the expansion and helping export Uruk material culture and techniques across Mesopotamia.

While it isn’t confirmed, one reason that is speculated for the decline of Uruk is the shifting river. When the river shifted more towards the west, as rivers do move and change course over time, the irrigation canals dried up by 4th century CE.

How Temples in Uruk Fused Religion with Political Power

Before Uruk turned into a sprawling human settlement, temples already played an important role in everyday life and religion. The great temple complex of Eanna, Inanna’s shrine, and Anu, the sky-god’s domain, were places of worship as well as engines of authority, wealth, and political legitimacy.

These temples sat atop elevated platforms, visible across the land. One of the more famous ones is the White Temple on the Anu Ziggurat. This symbolized the power of the gods, they were above regular people, high up in the land and sky.

These temples were not just places of worship. They owned large areas of land, including fields and flocks, and ran workshops. Their storehouses kept grain, oil, and textiles. Priests and scribes kept careful records of offerings and rations, managed crafts, organized irrigation, and directed labor during busy seasons. By controlling these resources, temple leaders decided who received food, who had jobs, and who worked for others.

How Modern Excavations at Ur Deepened Our Understanding of the Past

Sir Leonard Woolley began excavating Ur in the 1920s, bringing the ancient city back into view after centuries buried in the sands. His work at the Royal Cemetery made headlines, but Ur’s story did not end there. Today, archaeologists use new technologies like satellite imaging, ground-penetrating radar, and digital 3D mapping to uncover more about the city and the people who lived there.

Archaeologists now look at Ur as part of a larger network of cities connected by rivers and canals. Using remote sensing, they have traced ancient waterways that once linked Ur to other settlements. This has changed how we understand trade, irrigation, and how people moved across southern Mesopotamia. Recent excavations have also found domestic areas that earlier digs missed. These discoveries include clay tablets, cooking hearths, and children’s burials, which help us learn about the daily lives of ordinary people, not just the elite.

New scientific methods, such as isotopic and residue analysis, provide information that written records do not. Researchers have found traces of imported materials like lapis from Afghanistan, copper from Oman, and cedar from Lebanon, showing that Ur was part of early long-distance trade.