The presidency is the much sought-after golden fleece of American politics, which very few attain. Even otherwise successful politicians like Henry Clay, Walter Mondale, and John McCain, have an air of failure linked to their names because they failed to become US president. Ironically, for a few of those who did make it, their rise to the presidency is the source of a reputation for failure. Here are five men whose presidencies may have been the low point of their careers.

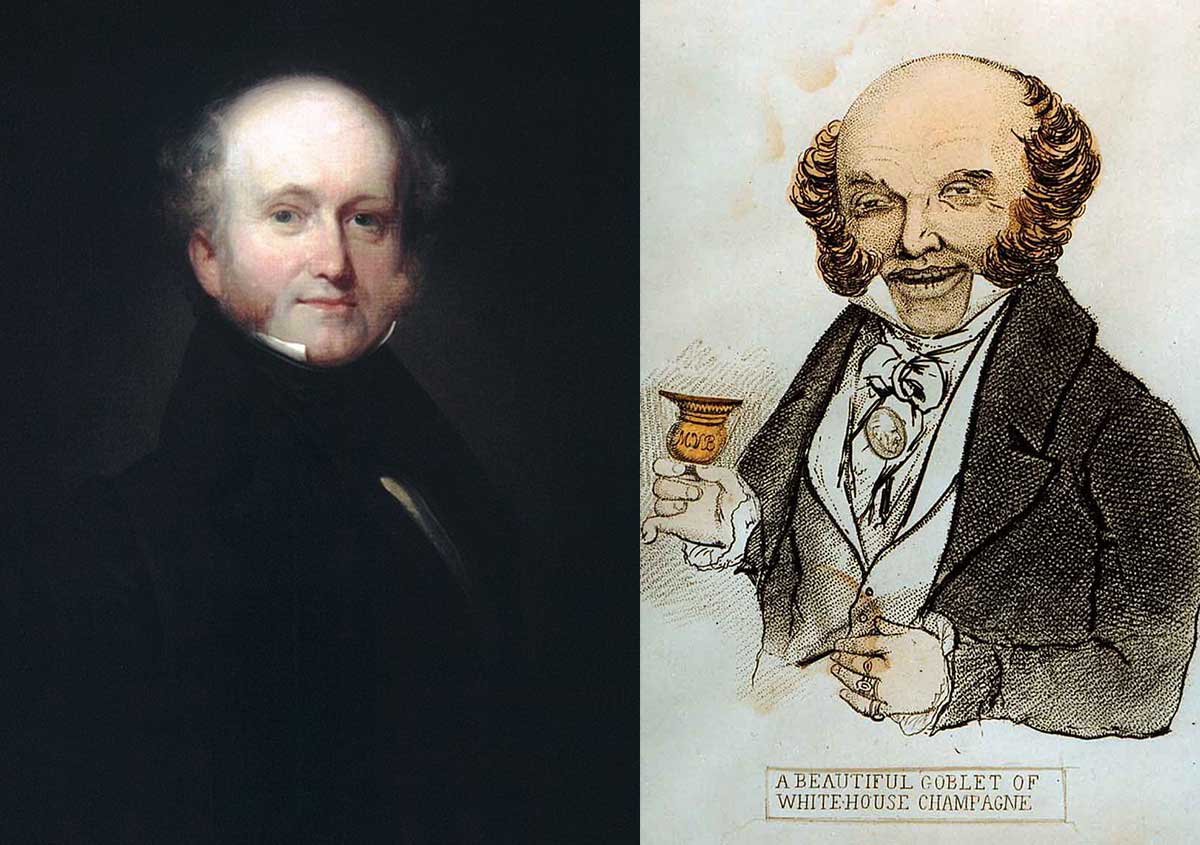

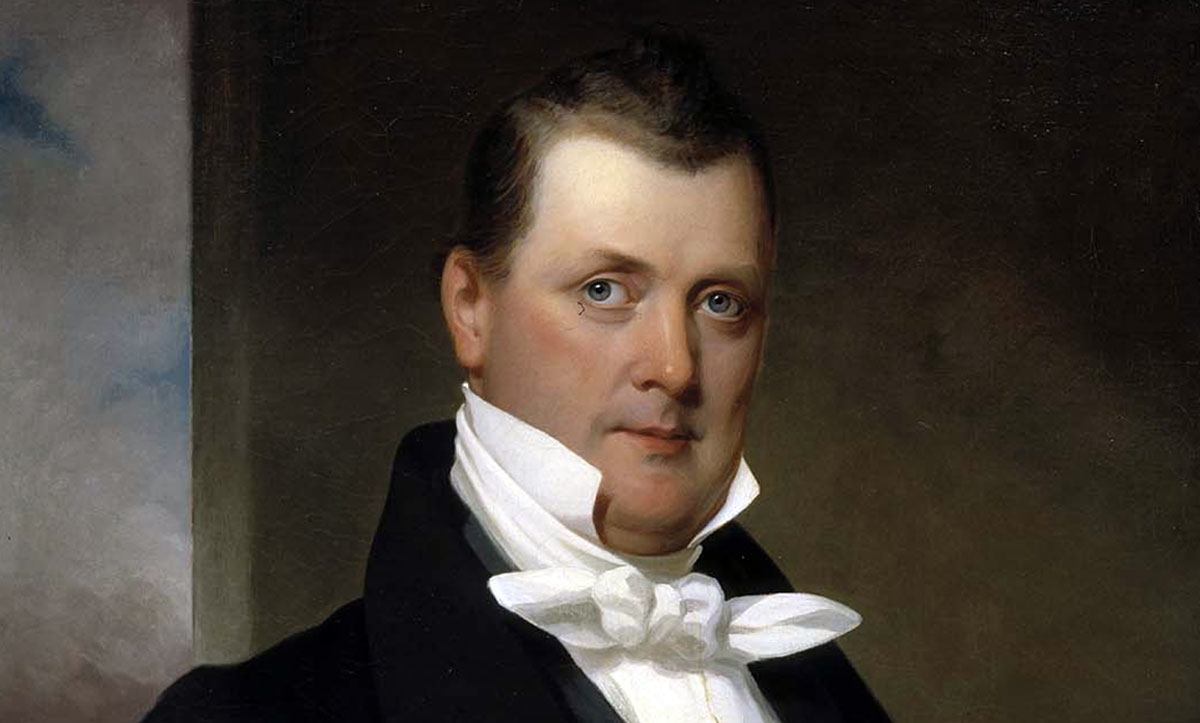

1. Martin Van Buren (1782-1862), President (1837-41)

Born in 1782 in upstate New York, Van Buren became a skilled and politically connected attorney in the early 19th century. Between 1808 and 1820, he scaled a series of New York political posts while building a base of support and maneuvering between factions.

Unlike many of the idealistic, elitist, founding fathers, Van Buren believed in taking politics straight to the people, campaigning openly, networking, and intriguing. In the early 19th century, the property qualifications for white men to vote were dropping, making politics a more populist business. The “Little Magician” as he became known used his knowledge of political alignments to become a power in New York State.

Starting in the 1820s Van Buren helped to bring party politics to the national stage as a senator. He became a leader of war hero Andrew Jackson’s faction, helping to organize it into the Democratic Party, now the oldest surviving political party in the world. With Van Buren’s organizational help, Jackson was elected to two terms as president on his image as a rough-and-tumble man of the people. During Jackson’s tenure (1829-37) Van Buren was a leading power behind the throne.

A father of modern politics and the Democratic party, Van Buren’s star began to fall when his own turn in the White House came in 1837. The financial Panic of 1837 hit just a few months into his term, casting a pall over his years in office.

Worse yet, by the 1840 campaign season, the opposition Whig party was using the Little Magician’s tricks against him. In the mold of the Jackson campaign, the Whigs portrayed their candidate, William Henry Harrison as a self-made frontiersman, and Van Buren as a big city fancy-boy, an image the latter could not shake. The populist Harrison campaign connected with voters and sent “Martin Van Ruin” packing after one term.

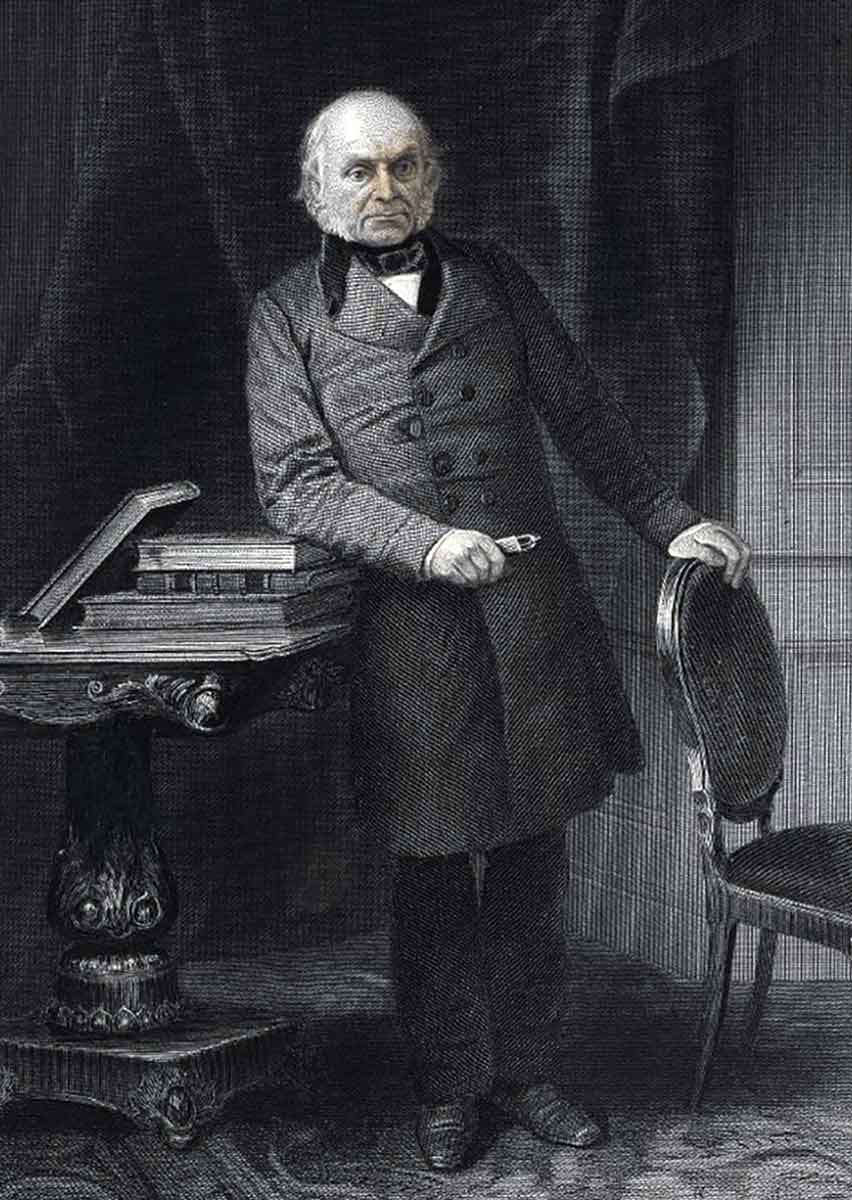

2. John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), President (1825-29)

If not for his presidency, John Quincy Adams might be counted as one of the most accomplished men of his age. The son of second President John Adams, Quincy carved out a life of service that started in his 20s. While his dad’s role got him started in government, the son did not rest on his family’s reputation. By the 1820s, he had arguably eclipsed his old man’s pre-presidential career.

Starting in the 1790s, the younger Adams served as minister (ambassador) to the Netherlands, and then Prussia. In 1809, President Madison appointed Adams as the first ever US minister to Russia. While still in Europe he was tasked to lead the US delegation in peace talks with Britain which ended the War of 1812.

In between diplomatic posts, he found time to serve as senator from Massachusetts. Finally, as secretary of state under James Monroe (1817-25) Adams crafted the Monroe Doctrine, a guideline to keep Europe out of Latin America, which would remain US policy for over a century.

This impressive rise was followed by an ill-starred presidency. Elected by the US House in 1824, with a minority of the popular vote, Adams was seen by opponents as having stolen the election from the popular Andrew Jackson.

Congress tried to block the new president’s ambitious program of infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, the tariff was an even more controversial issue, and Adams signed a tariff bill that only succeeded in angering the South. On a personal level, Adams could be difficult to work with and kept a running feud with his hot-tempered vice president, John Calhoun. Unsurprisingly, the 1828 election threw Adams out of office in favor of Jackson.

After his presidency, Adams was back in his element, now as a leading voice for the antislavery movement in Congress. Representative Adams helped to defeat the “gag rule” against debating slavery in the House of Representatives, and successfully argued the case of the Amistad mutineers in front of the Supreme Court, helping them regain their freedom. In contrast to Amistad, it is hard to picture anyone making a film of Adams’s four years in the White House.

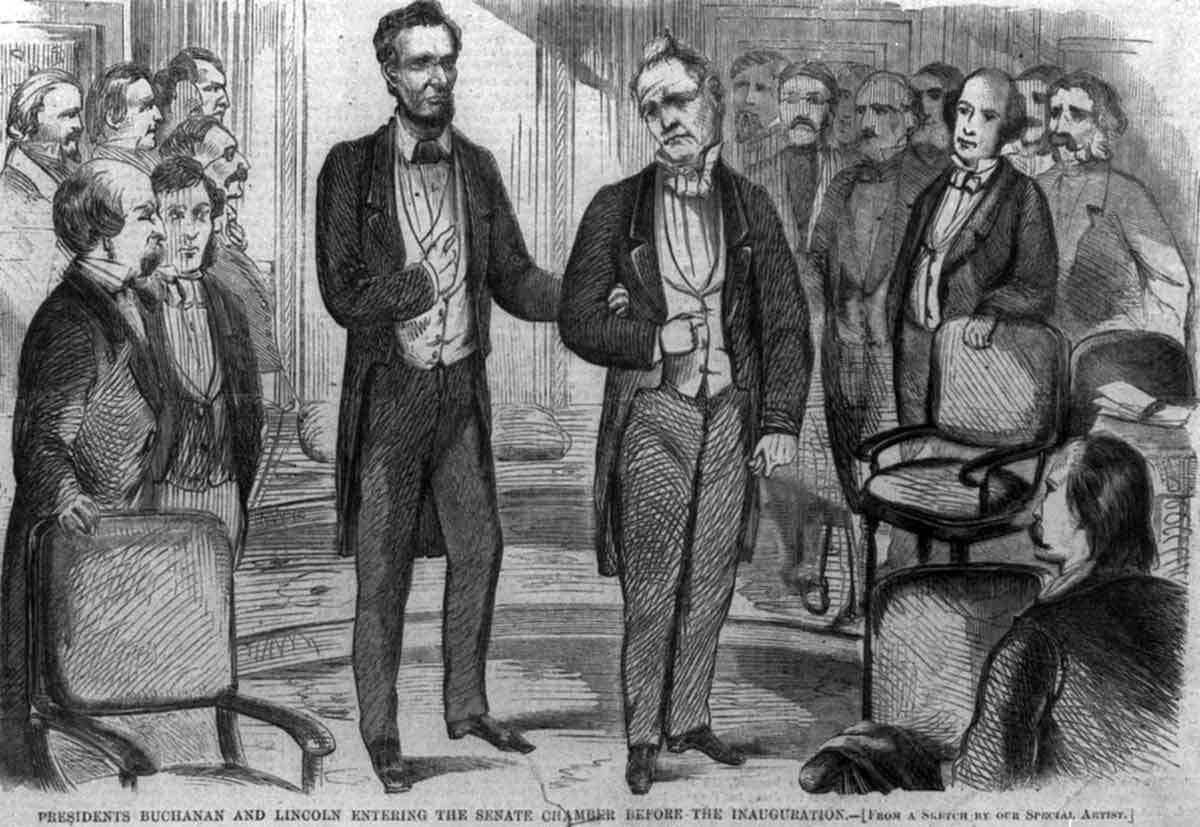

3. James Buchanan (1791-1868), President (1857-61)

Buchanan is often ranked last in surveys of presidential historians. As the president preceding Lincoln, he had a tough place in history, almost anyone would look mediocre next to the Great Emancipator. Judged on its own merits, however, Buchanan’s administration still looks like a failure.

As a young attorney in Pennsylvania, Buchanan built a record of success that fellow lawyer Abe Lincoln could only dream of. By the time he was 30 and entered national politics, he had already amassed over $250,000 (more than $5 million in 2024).

Rising first in the US House, then the Senate, Buchanan became a leading Democrat and a national figure, serving as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. As secretary of state under James Polk (1845-49), he successfully negotiated the Oregon Territory boundary with the UK. In the Pierce administration (1853-57) he was called to service again, as the US ambassador to Great Britain.

All the while, OPF (Old Public Functionary) as Buchanan called himself, was repeatedly angling for the top job of president. His turn finally came in 1856 when the Democrats gave him the nod, and he won that year’s election. Little good followed.

The Kansas territory was awash in violence as competing pro and anti-slavery mobs fought to dominate it before statehood. Rival territorial governments sprouted, and Buchanan favored the proslavery government, an unpopular move since it clearly did not have a mandate from Kansas voters.

Meanwhile, the economy tanked in the Panic of 1857, and the president did nothing about it. To top things off, Buchanan’s protégé, Congressman Daniel Sickles murdered a man in broad daylight on Pennsylvania Avenue.

When Lincoln was elected in 1860 and the South started leaving the nation, Buchanan did little—seeming inept to critics, or even partial towards the South. As Lincoln assumed office, the outgoing president told the newbie “If you are as happy, my dear sir, on entering this house as I am in leaving it … you are the happiest man in this country.”

4. William Howard Taft (1857-1930), President (1909-13)

Taft is often remembered as the fattest US President, weighing in the 300s. While this might be unfair to a man with his distinguished legal career, Taft did little during his presidency that stands out. Taft’s heft may have even saved him from being a forgotten president like Chester Arthur or Benjamin Harrison.

Born to a political Ohio family, Taft excelled in law from an early age, dreaming of sitting on the Supreme Court. In 1886, he married Helen “Nellie” Herron, an ambitious woman who wanted him to use his talents to pursue elected office. She became a driver of his political career, while he mostly just wanted to be a judge.

As an attorney, judge, and law professor, the young Republican came to the attention of President McKinley (1897-1901) who appointed him Governor of the Philippines in 1900. In turn, Taft’s friend Theodore Roosevelt (1901-09) made him Secretary of War. Taft excelled in these roles. By the 1908 election, Secretary Taft was Roosevelt’s right-hand-man and chosen successor. Taft, now the reluctant Republican nominee, easily beat Democrat William Jennings Bryan.

At the summit of power, Taft was not ambitious. He expanded some of Roosevelt’s policies against business trusts, but also became more conservative than his predecessor, reopening some public lands that T.R. had closed to commercial exploitation. Taft had moved away from the Roosevelt wing of the party.

As the election of 1912 neared, Teddy Roosevelt now came back as a fierce critic of his former aide. Attacking Taft from the left, he ran in the 1912 election for the Progressive Party, calling Taft a “fathead.” Taft called Roosevelt a “demagogue” and wept over the feud with his old mentor.

Neither man won that brutal election, as progressive Democrat Woodrow Wilson swooped in for victory. Sandwiched in between the activist presidencies of Roosevelt and Wilson, Taft’s administration seems like a footnote in history.

Taft was not a lucky president either: First Lady Nellie had a stroke early in the administration, taking time to recover. Chief aide Archibald Butt died on the Titanic, while Vice President James Sherman died just days before the election of 1912.

The post-presidency was a notable improvement, as Taft settled into a more pleasant role teaching law at Yale. In 1921, Taft’s lifelong dream came true, as he was appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by President Harding.

5. Herbert Hoover (1874-1964), President (1929-33)

A plucky orphan with a love of geology, Hoover graduated from Stanford University in 1895. By the time he was 40, the geologist whiz kid had made his name and fortune inspecting and supervising mines all over the world, accompanied by his wife Lou, a geologist in her own right.

The start of World War I in 1914 moved Hoover into public service. That year, the State Department tapped him to use his organizational skills to get over 100,000 stranded Americans out of Europe. Upon America’s entry into the war (1917), he was put in charge of the US Food Administration and became an economic advisor to President Wilson. After the war ended, Hoover headed relief efforts to feed the tens of millions starving in war-ravaged Europe and Asia.

A storm of publicity now hovered around Hoover, including presidential buzz. Despite his service in the Democratic Wilson administration, Hoover was a Republican and was given the job of commerce secretary under Presidents Harding (1921-23) and Coolidge (1923-29)

A dynamic force in conservative administrations, Hoover was constantly suggesting improvements, to his boss’s chagrin. Coolidge said of Hoover “That man has offered me unsolicited advice for six years, all of it bad.” Much of the country disagreed, and elected Hoover president in 1928.

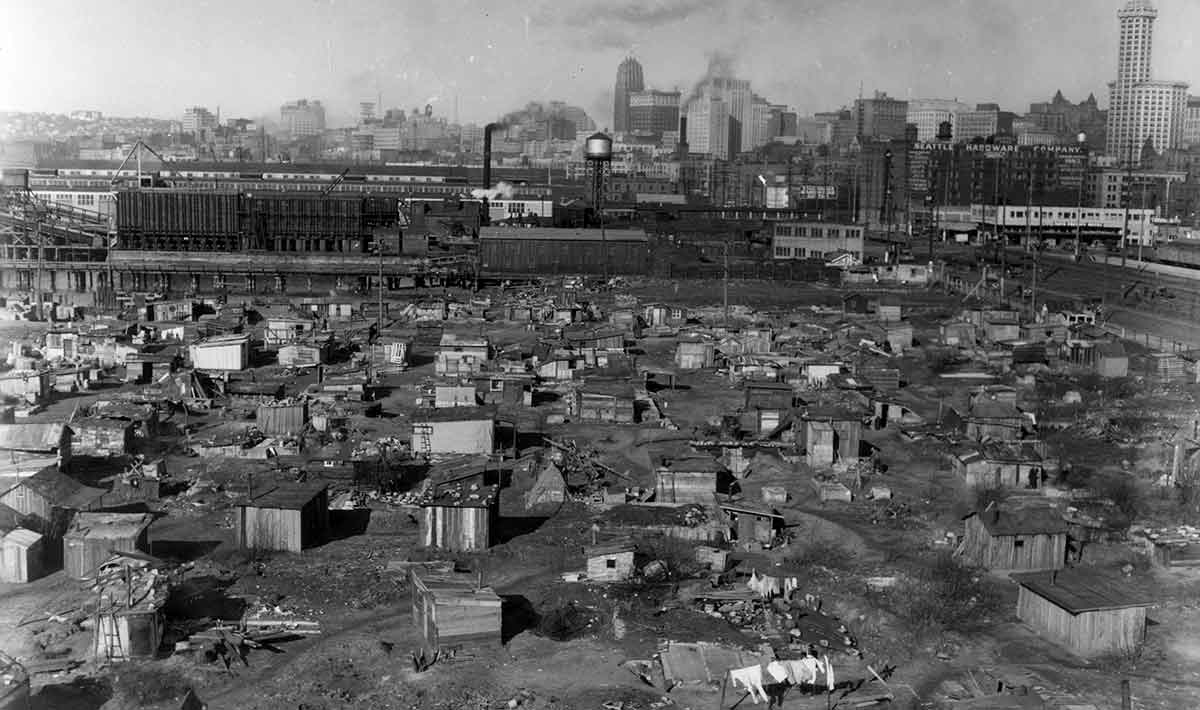

The stock market crash in October 1929 determined Hoover’s presidential legacy, as the US led the world into the Great Depression. Hoover’s philosophy of volunteerism and limited federal intervention was not enough for many who wanted immediate relief. His tariff hike in 1930, only hurt trade, deepening the Depression.

Ironically, the man who fed millions around the world was now seen as indifferent to his own people’s suffering. Shantytowns were “Hoovervilles,” and newspapers were dubbed “Hoover blankets.” Hoover lost the 1932 election to Franklin Roosevelt in a landslide.

A washed-up ex-president before 60, Hoover nevertheless remained active in his three remaining decades. The Roosevelt and Truman administrations recognized his usefulness and asked the old logistics pro to head relief efforts for World War II-related famine. In the ‘40s and ‘50s, Hoover was also tapped to help reorganize the executive branch. By the time of his death in 1964, the once-hated president had regained much respect as an elder statesman and humanitarian.

Bibliography:

The American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers. “Awards and Scholarships: Herbert Clark Hoover (SME)”. Accessed December 2, 2024.

https://aimehq.org/what-we-do/awards/aime-william-lawrence-saunders-gold-medal/herbert-clark-hoover

Burns, James M. and Dunn, Susan. The Three Roosevelts. New York: Grove Press (2001)

C-SPAN, Presidential Historians Survey 2017. Accessed December 2, 2024.

https://www.c-span.org/presidentsurvey2017

Baker, Jean H. Essential Civil War Curriculum. “James Buchanan.” Accessed December 5, 2024.

https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/james-buchanan.html

History.com “Hoovervilles” Updated: October 4, 2022. Accessed December 3, 2024.

https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression/hoovervilles

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Herbert Hoover.” Accessed December 03, 2024. https://millercenter.org/president/hoover.

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “James Buchanan.” Accessed December 03, 2024. https://millercenter.org/president/buchanan.

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “John Quincy Adams.” Accessed December 03, 2024. https://millercenter.org/president/jqadams

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Martin Van Buren.” Accessed December 03, 2024. https://millercenter.org/president/vanburen.

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “William Taft.” Accessed December 10, 2024. https://millercenter.org/president/taft.

National Archives: Herber Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. “Lou Henry Hoover: Early Life.” Accessed, November 28, 2024.

https://hoover.archives.gov/exhibits/lou-henry-hoover

National Park Service: William Howard Taft National Historic Site. Accessed December 4, 2024.

https://npshistory.com/publications/wiho

President James Buchanan: 15th President of the United States Under the Constitution of 1787: March

https://www.jamesbuchanan.org

Silbey, Joel H. Martin Van Buren and the Emergence of American Popular Politics. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. 2002

Swanberg, W.A. Sickles the Incredible. Gettysburg: Stan Clark Military Books (1984)

U.S Department of Commerce, Commerce Research Library. “Secretary of Commerce, Undersecretary of Everything Else: Herbert Hoover as Department of Commerce Secretary, 1921-28.” Accessed November 30, 2024.

https://library.doc.gov/digital-exhibits/hoover-digital-exhibit

The White House. “Herbert Hoover: The 31st President of the United States.” Accessed November 29, 2024.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/herbert-hoover/

The White House Historical Association “Helen Taft.” Accessed December 3, 2024.

https://www.whitehousehistory.org/bios/helen-taft