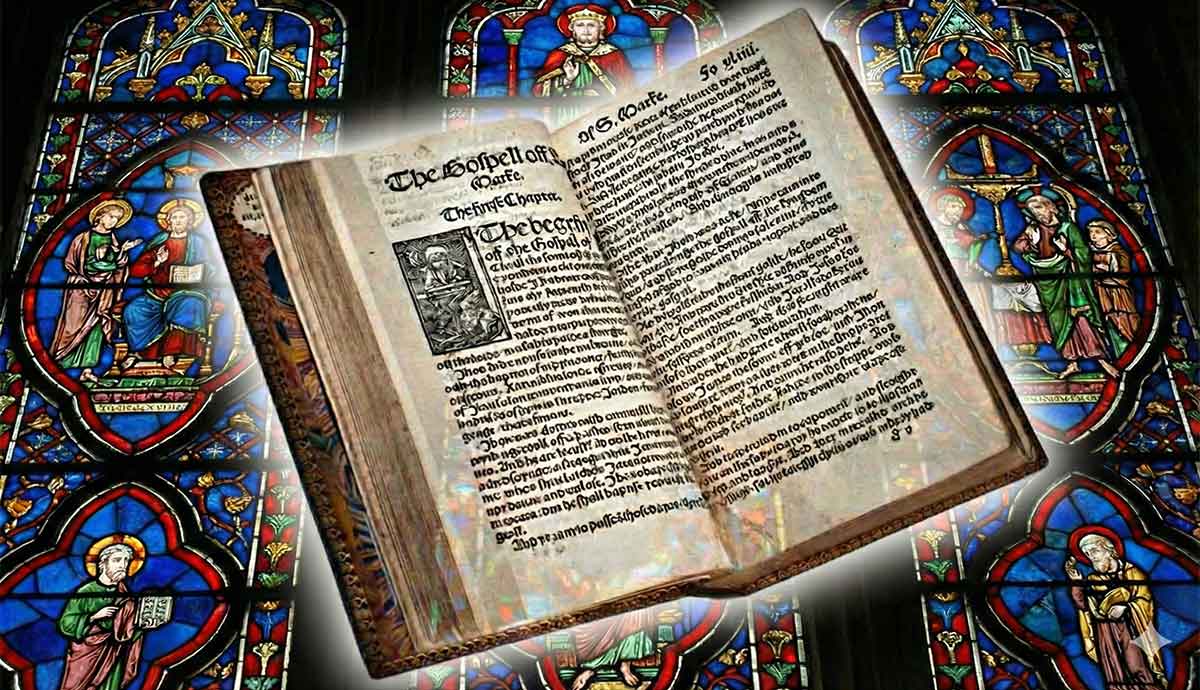

Today, we take verses in the Bible for granted but they are a relatively new phenomenon in the history of the Bible, whether the Hebrew or the Christian version. For centuries there were no chapter or verse divisions in the Bible. Thanks to Robert (Stephanus) Estienne, the Bible has verse divisions that make referencing specific sections of scripture much easier. Scholars today have access to older manuscripts that do not contain some of the verses that Estienne numbered. Translators of newer versions of the Bible had to deal with the resulting discrepancies.

The History of Verses

Scribes who wrote the ancient manuscripts of the Bible in Greek and Latin used scriptio continua and capitalis quadrata. These terms refer to continuous text with no spaces between words, sentences, or paragraphs, and text in capital square letters. The reader had to determine where the separation between words is, where sentences ended, and which sections of text made sense as a unit. Understandably, it was not easy to read and make sense of a document written that way.

In the 5th century, Jerome, a Church Father, started dividing parts of the Bible into units he called pericopes. These pericopes were usually material that made sense as a unit, such as parables, miracles, or stories from the gospels. It was not until the 12th century that chapter divisions similar to what we know today saw the light. Many scholars credit Stephen Langton, a professor at the University of Paris, for the chapter divisions, but other editors and scribes most likely contributed to the work. These divisions were necessary to make referencing passages easier in the educational environment. The result was the Paris Bibles with standardized chapter divisions in a single volume that contained the Old and New Testaments.

The first English Bible to follow the chapter divisions of Langton was the Wycliffe Bible, published in 1382. The chapter divisions made referencing much easier but were still insufficient in an academic environment where progressively more detailed and in-depth research occurred. 66 years later, in 1448, Isaac Nathan ben Kalonymus further divided the Tanak, or Hebrew Old Testament, into verses. It was part of his compilation of the first Hebrew concordance named Meïr Netib. Nathan was a French Jew and philosopher. The verse divisions made it possible to list the location of a word with much more specificity than was possible before.

It took more than a century for New Testament verse divisions to become widely accepted. An attempt by Santes Pagnino, an Italian Dominican biblical scholar, never gained traction, likely because the verses were too long. A Parisian printer, Robert (Stephanus) Estienne, produced a numbered edition of the Greek New Testament in 1551. The same numbering is reflected in a French edition dated 1553. In 1555, a Vulgate version of the Bible was the first to integrate verses into the text. Estienne’s system is what most contemporary Bibles contain. Two years later, in 1557, the first English Bible with verse divisions saw the light when William Whittingham published his translation. The Geneva Bible of 1560 was the first to use chapters and verses in the text.

Differences in Verse Divisions

The division of the Bible into verses preceded the King James Version. This version remains popular among many Christians although it is not as easy to read as newer translations. The first King James Version of the Bible saw the light in 1611. Today, many Christians hold to the “King James only” view, believing it was the best and most accurate translation of the Bible. That is factually correct.

Since the 17th century, many older manuscripts have been discovered that omit several verses and passages that the Textus Receptus includes. It follows that differences in manuscripts used in translation may result in differences in verses, which we see in several Bibles today. The New International Version and English Standard Version are some of the most popular and commonly used translations of the newer versions. Translators of these versions were aware of the differences and dealt with them in several ways to address concerns and educate readers on the reasons behind the discrepancies.

The longer ending of Mark

Early manuscripts of the Gospel of Mark, such as the Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus, do not include Mark 16:9-20. Translations that used these or similar manuscripts as a source use footnotes, brackets, or both, to address the issues that arise. The Revised Standard Version (RSV), New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), New American Standard Bible (NASB), Holman Christian Standard Bible HCSB), and English Standard Version (ESV) have Mark 16:9-20 added in brackets and provide a footnote mentioning that these verses do not appear in older manuscripts. The New International Version and New English Translation do not have the text in brackets but provide a footnote explaining the dubious text.

The Woman Caught in Adultery

In the King James Version of the Bible, John 7:53-8:11 relates the story of a woman caught in adultery. Jesus famously said: “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.” Newer translations based on older manuscripts that do not contain this narrative still include it in their versions of the Bible using brackets, footnotes, or both to indicate its absence from the sources they used. Should they have left such narratives out of the text, it would exacerbate the problem with verse referencing between Bible versions.

The Johannine Comma

The King James Version includes several other verses that translations from older texts do not have. The Comma Johanneum, or Johannine Comma, is a prime example. The term refers to the added text to 1 John 5:7-8 that, in the King James Version, reads: “For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one.” the English Standard Version renders it: “For there are three that testify: the Spirit and the water and the blood; and these three agree.”

Single Verse Differences

Some differences impact only single verses in different translations. Let’s look at a couple of examples.

In the King James Version, Acts 8:37 reads: “And Philip said, If thou believest with all thine heart, thou mayest. And he answered and said, I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God.” The International Standard Version, English Standard Version, and New International Version omit this verse. The jumps from verses 36-38 align with the correlating verse numbering in other translations. The English Standard Version has a footnote: “Some manuscripts add all or most of verse 37” and then lists the verse. Because the verse listed is not in the source manuscript, they revert to later manuscripts that list it.

We find a similar situation in Matthew 17:21. The King James reads: “But this kind does not come out except by prayer and fasting.” The New International Version (NIV), the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), and the English Standard Version omitted the verse. The International Standard Version (ISV) lists this verse, although it omitted Acts 8:37 in the previous example. Sometimes, the weight assigned to sources influences the inclusion or omission of verses. Though the NIV, NRSV, and ISV use the Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus, and Codex Alexandrinus as sources, the ISV seems to give more credence to the Alexandrinus by including the verse not listed in the other two sources.

The New King James Version is, like its predecessor, based on the Textus Receptus. To acknowledge the omission of verses not found in the older manuscripts, it lists these verses in cursive. Similarly, the ASV, translated from the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus, does not omit verses that the Textus Receptus includes. It lists those verses in cursive, acknowledging their later addition. Cursive text is a way to highlight the differences between sources and retail the verse correlation between translations.

There are many more examples that could be used, but the basic reasoning behind the differences in verse remain essentially the same: the source manuscripts differ.

Verses in the Bible: In Conclusion

Verses in the Bible came about during the 1400s thanks to Rabbi Nathan as far as the Old Testament is concerned, and in the 1500s in the New Testament due to the work of Robert (Stephanus) Estienne. The discovery of older manuscripts that do not list some passages or verses included in the Textus Receptus caused later translations to use brackets, footnotes, or both to address the discrepancies between versions. The New King James and American Standard Versions of the Bible use cursive text to denote verses that appear in the Textus Receptus but that older text sources do not have.