Vibia Perpetua was a Roman noblewoman who converted to Christianity early in the 3rd century CE. Her refusal to worship a Roman god resulted in her arrest and, ultimately, her execution in 203 CE. Only 22, with a baby son, she kept a diary chronicling her last days in prison, a diary which represents the earliest writing from a Christian woman that we have today.

Christian Martyrdom in the Roman Empire

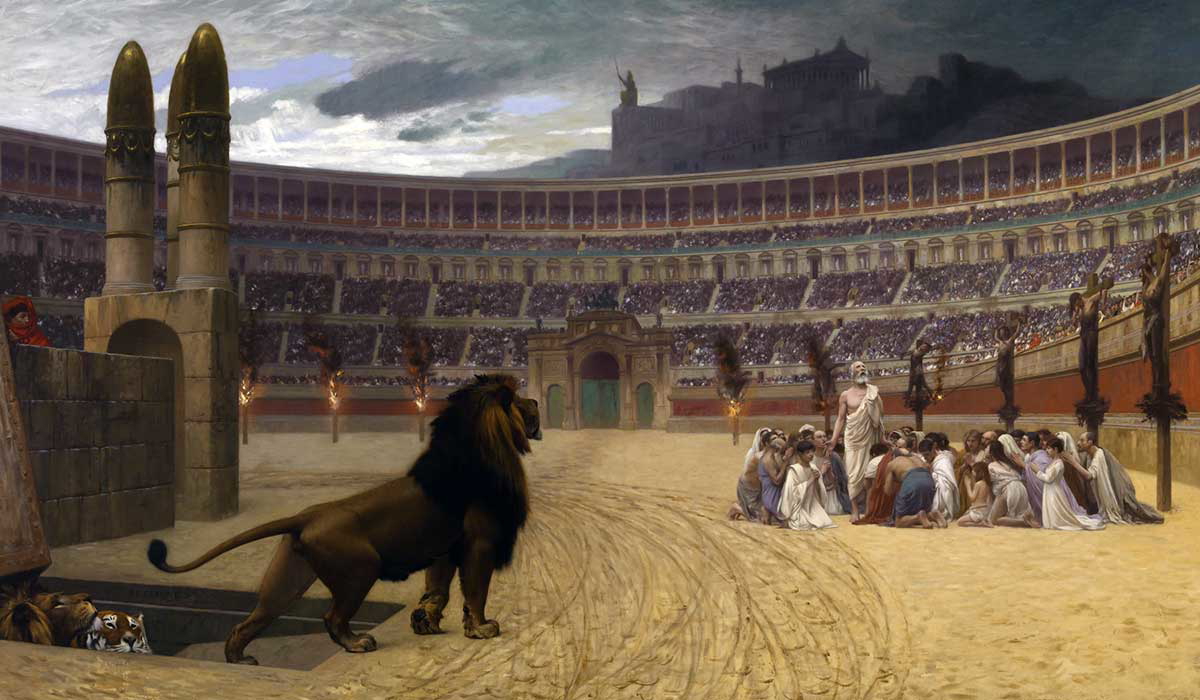

The Roman Empire’s persecution of Christians started only a couple of decades after Christ’s death and resurrection with the notorious Emperor Nero (37-68 CE), who reigned from 54 until his death. Famously but incorrectly thought to have fiddled while Rome burned in a devastating fire in 64, he blamed the conflagration on the Christians, although it was rumored that he himself started the blaze to make way for a series of buildings he wanted to establish on the land, including an elaborate palace for himself.

This event may well have kicked off the persecution of Christians, however, the Romans had begun to see them as a threat prior to Nero’s reign. The Romans were polytheists and probably would not have had a problem with Christ’s followers if they merely added Jesus to the Empire’s pantheon of gods and worshipped Roman deities (including the emperor) as well. But the Christians refused to do that. They worshiped the God of the scripture and no other. This failure to fit in made them a threat to the Roman Empire because, as dissidents, they were liable to cause trouble. Vibia Perpetua was viewed as one such dissident.

Who Was Vibia Perpetua?

Vibia Perpetua was born in 181 in Carthage, North Africa, into a wealthy family. She married a man of equal standing and bore a son. While her mother and one of her brothers were Christians, her father and husband were not. At the time of her arrest, she was a catechumen, that is, a convert to Christianity who was receiving the instruction and discipline necessary for her to be baptized as a Christian. When told she must make sacrifices to a Roman god, she refused and was arrested along with her friend and servant, Felicity, who was eight months pregnant, Felicity’s husband, Revocatus, and two fellow Christians, Secundulus and Saturninus, the latter of whom was a priest from Rome.

Upon hearing of their arrest, another catechumen, Saturus, willingly turned himself in to the Roman authorities. Perpetua calls him “brother” in her diary. He may have been her biological brother, or she may have used the term to mean that he was her brother in Christ. Different sources say different things. Whatever the case, he chose to be imprisoned and sent to the arena, thereby indicating his closeness to Perpetua, to the others, and to God.

Montanism

Although not all scholars are in agreement, a good many of them believe that Perpetua and her fellow prisoners belonged to a Christian sect called Montanism that arose in the last half of the 2nd century. It was named after a former pagan priest named Montanus who hailed from Phrygia (modern-day central Turkey). He, along with two women, Priscilla and Maximilla, called their religious movement “the New Prophecy,” and proclaimed themselves as God’s prophets. Martyrdom represented one of their key doctrines along with speaking in tongues and uttering prophetic words. Some early Christian Fathers considered them heretics, partly because of their unusual practices and partly because they thought them guilty of Monarchianism, that is, the belief that God is one indivisible being, not a Trinity. Ultimately, the Church excommunicated Montanus.

The issue of martyrdom was particularly off-putting to the early Church Fathers as choosing it seemed tantamount to committing suicide, which the Church hotly condemned. No one should want to die, they noted, but when it came to the Montanists, it seemed like they went looking for reasons to be put to death. From the Montanist point of view, it looked like other Christians were keeping silent about their faith rather than witnessing boldly to others because of their fear of negative repercussions.

Tertullian

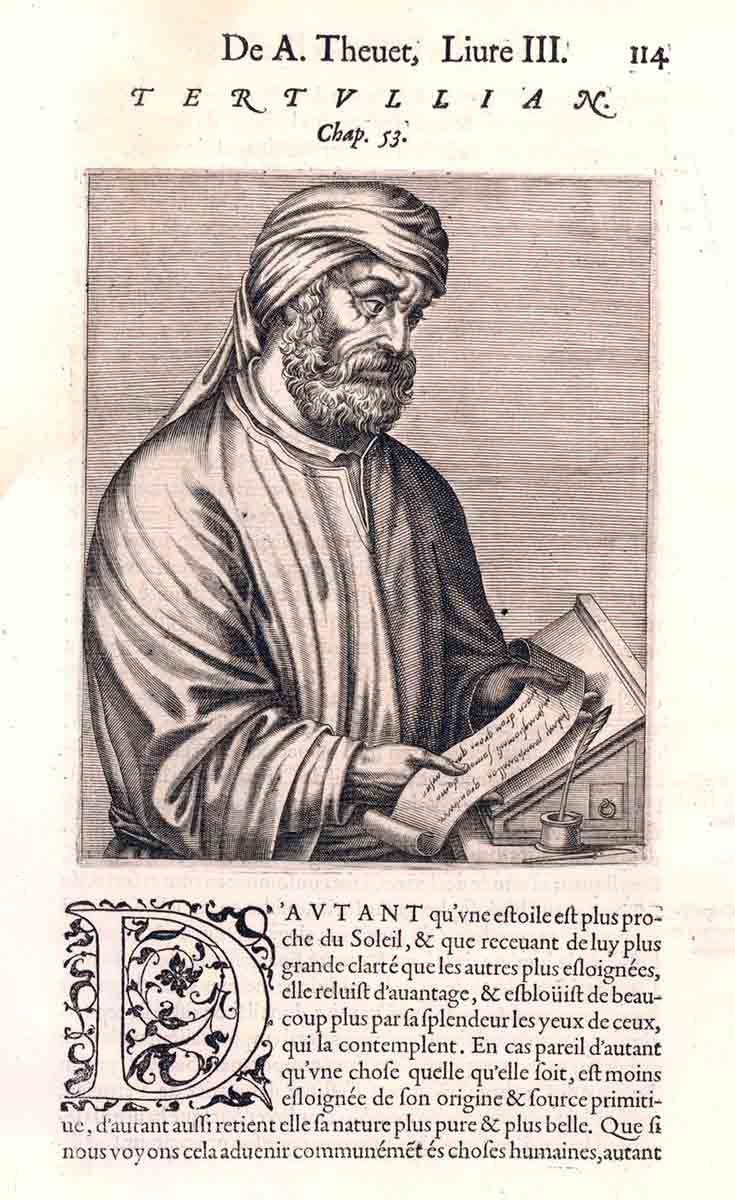

Tertullian, one of the leading Christian figures in Carthage, initially accepted, lauded, and defended the Montanists. Born around 145 CE to a Roman centurion, he lived a licentious lifestyle until becoming a Christian in about 185 CE. He was attracted to the Montanists because of their moral living and, according to some scholars, their stalwart martyrdom that he witnessed in the arena. Some scholars suggest that he grew disenchanted with the Montanists and founded his own church with followers referred to as Tertullianists. Others suggest it was just another Montanist church bearing his name.

Septimius Severus

Septimius Severus, emperor from 193 to 211, initially tolerated Christianity, supposedly because a Christian physician named Proculus healed him of an ailment. The man remained in the emperor’s household and was held in high regard.

However, things changed drastically at the onset of the 3rd century when Severus, in 202, decreed that no one was allowed to convert to Judaism or Christianity. Scholars can only speculate on what prompted this edict. Some suggest that Christianity was spreading so quickly that it threatened the Roman way of life. Forbidding converts to the religion would slow that pace down and, perhaps, halt it altogether. Others note that the Montanists prophesied that Christ was returning soon, and that signaled the demise of the Roman Empire. This, of course, did not go over well with the emperor, and it may have provided a reason for his sudden harsh stand against them.

Some scholars suggest that Severus’s attack on Christians arose from the fact that pagans despised them, accusing them of atheism, incest, and even cannibalism. In fact, it may have been Montanism itself that fueled their hatred, as some of the sect’s activities were similar to those of the sorcerers of the day.

Montanists insisted that they had a close relationship with the Lord and actually united with him as they entered into frenzied states of ecstasy when they called upon the Holy Spirit to give them word from God. They often spoke in tongues that sounded like mere babble to uninitiated observers. Sorcerers made the same claim about being close to the gods and behaved in a similarly bizarre manner while reciting incantations. Pagans blamed these “magicians” for their adversities, for natural disasters such as earthquakes, and for supposedly casting spells on people. To them, the Montanists seemed no different than these hated and feared sorcerers. This might have motivated Severus to deal with Christians harshly in an attempt to keep the peace.

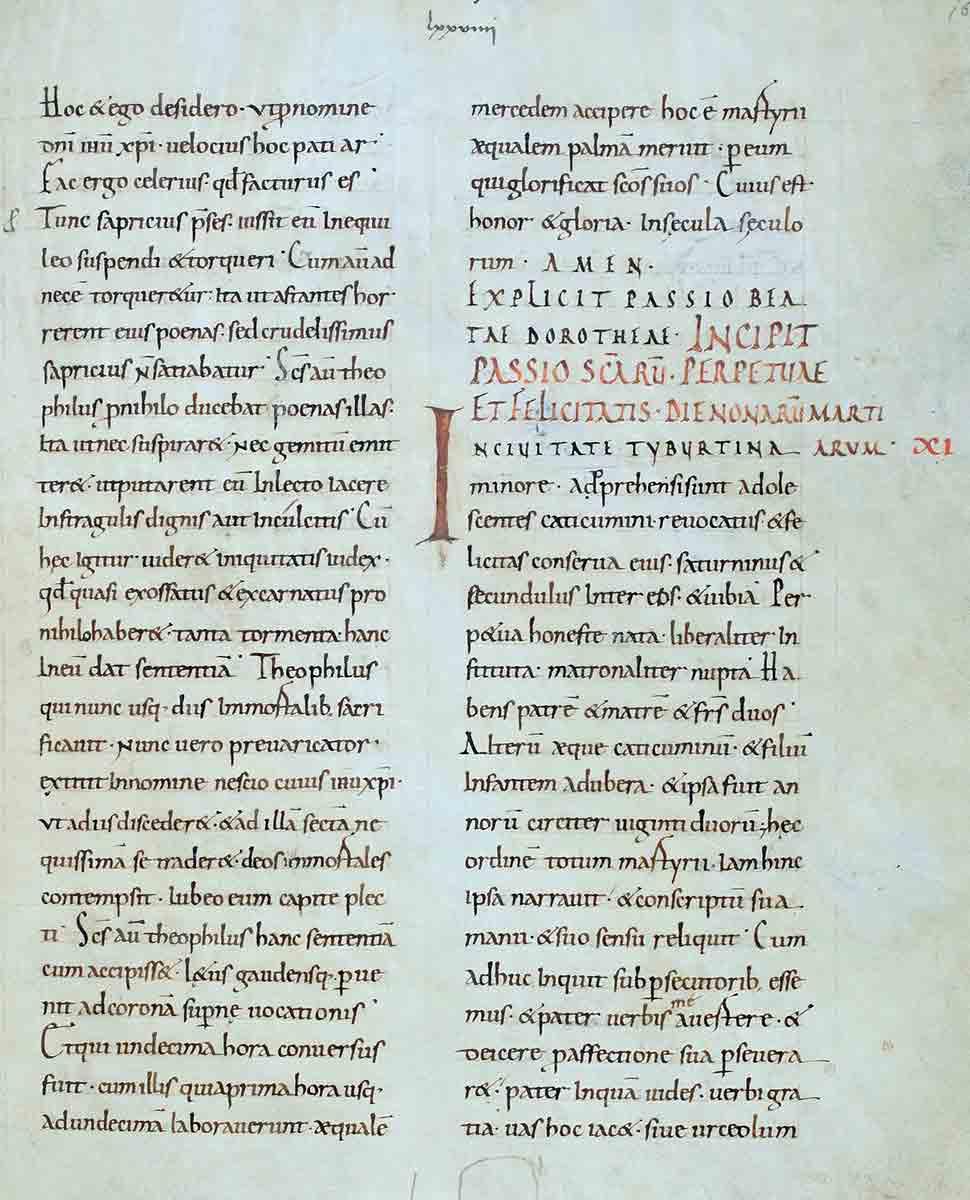

The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity

This, then, is the world in which Perpetua found herself. As an educated woman, she could read and write, and, while in prison, she kept a diary which today we know as The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity. At some point in time, an anonymous editor (possibly Tertullian) wrote an introduction for it and ended the manuscript with a description of Perpetua’s martyrdom. Scholars are almost unanimous in their belief that its central passage contains the woman’s words and no one else’s. In it, the martyr describes her discussions with her father as he begged her to denounce her beliefs. She wrote:

“While we were still with the persecutors, and my father, for the sake of his affection for me, was persisting in seeking to turn me away, and to cast me down from the faith.

‘Father,’ said I, ‘do you see, let us say, this vessel lying here to be a little pitcher, or something else?’

And he said, ‘I see it to be so.’

And I replied to him, ‘Can it be called by any other name than what it is?’

And he said, ‘No.’

‘Neither can I call myself anything else than what I am, a Christian.’”

Perpetua’s Visions in Prison

Saturus encouraged Perpetua to seek a vision from the Lord to determine whether she was to be martyred or if she would escape that fate. She described the vision that resulted, writing:

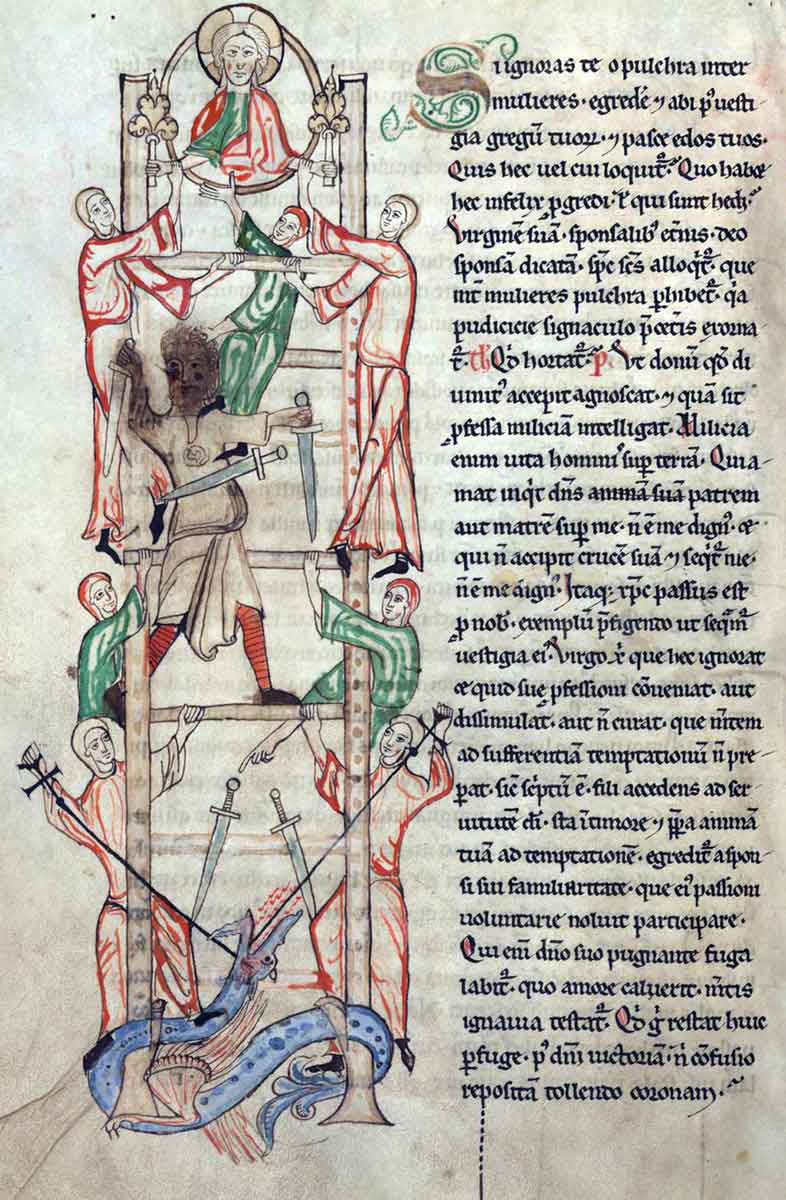

“I saw a golden ladder of marvellous height, reaching up even to heaven, and very narrow, so that persons could only ascend it one by one; and on the sides of the ladder was fixed every kind of iron weapon. There were there swords, lances, hooks, daggers; so that if any one went up carelessly, or not looking upwards, he would be torn to pieces and his flesh would cleave to the iron weapons. And under the ladder itself was crouching a dragon of wonderful size, who lay in wait for those who ascended, and frightened them from the ascent.

And Saturus went up first, who had subsequently delivered himself up freely on our account, not having been present at the time that we were taken prisoners. And he attained the top of the ladder, and turned towards me, and said to me, ‘Perpetua, I am waiting for you; but be careful that the dragon does not bite you.’ And I said, ‘In the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, he shall not hurt me.’ And from under the ladder itself, as if in fear of me, he slowly lifted up his head; and as I trod upon the first step, I trod upon his head.

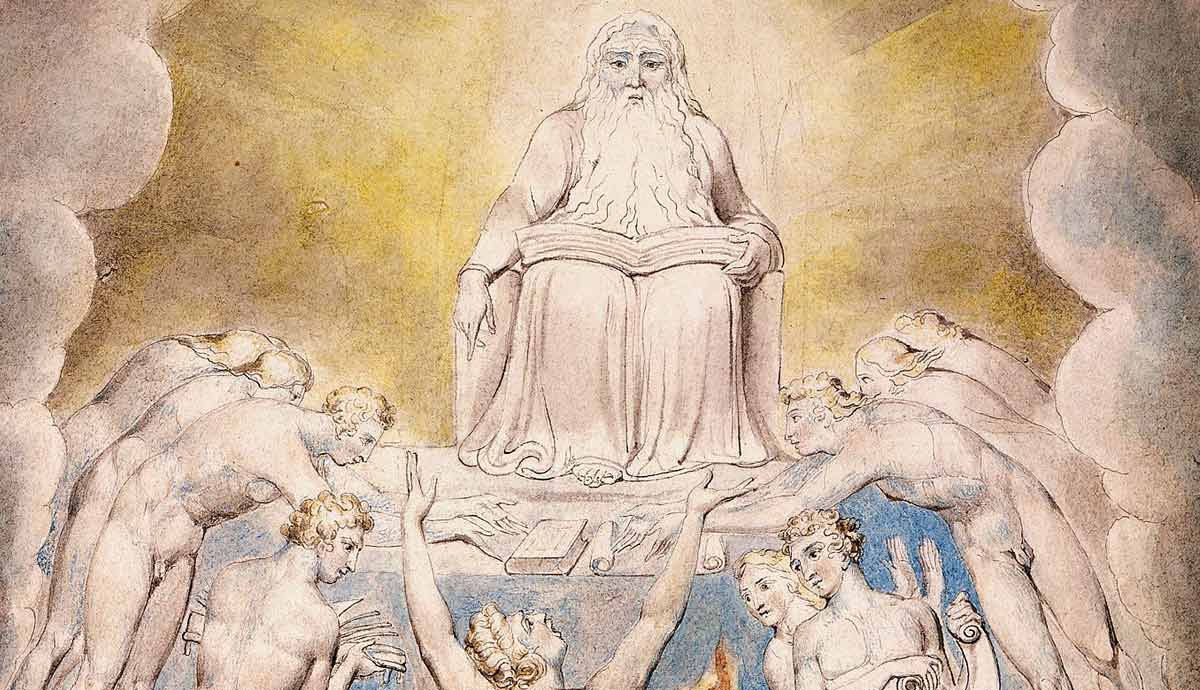

And I went up, and I saw an immense extent of garden, and in the midst of the garden a white-haired man sitting in the dress of a shepherd, of a large stature, milking sheep; and standing around were many thousand white-robed ones. And he raised his head, and looked upon me, and said to me, ‘Thou art welcome, daughter.’ And he called me, and from the cheese as he was milking he gave me as it were a little cake, and I received it with folded hands; and I ate it, and all who stood around said Amen. And at the sound of their voices I was awakened, still tasting a sweetness which I cannot describe. And I immediately related this to my brother, and we understood that it was to be a passion, and we ceased henceforth to have any hope in this world.”

Perpetua had two more visions while in prison. In one, she saw her brother, Dinocrates, who had died as a child. Believing him to be in purgatory, she had prayed for his salvation. In her dream, she saw him whole and, in her words, “translated from the place of punishment.”

In her final vision, Perpetua was led into an amphitheater where she did battle with an Egyptian warrior. She conquered him by rising in the air, kicking him, and stepping on his head, at which point a “man of great stature” presented her with a bough of golden apples. Perpetua understood this to mean that her fight was with the devil. The vision harkens back to Genesis, where God prophesied that “the seed of woman” would crush the serpent’s head (3:15). The verse refers specifically to Christ, who will defeat Satan once and for all at the end of time. Perpetua, knowing that she was “in Christ,” saw that she would defeat the devil, even in death, because death was nothing but the beginning of life in eternity with the Lord.

Saturus, too, had a vision that Perpetua recorded in her diary. In his vision, he saw himself, Perpetua, and others entering God’s presence in heaven. This confirmed to them that their deaths in the arena would be a victory for them and not a defeat.

Following this passage in Perpetua’s diary, the anonymous editor takes over and describes the death of the martyrs.

Martyred in the Arena in Carthage

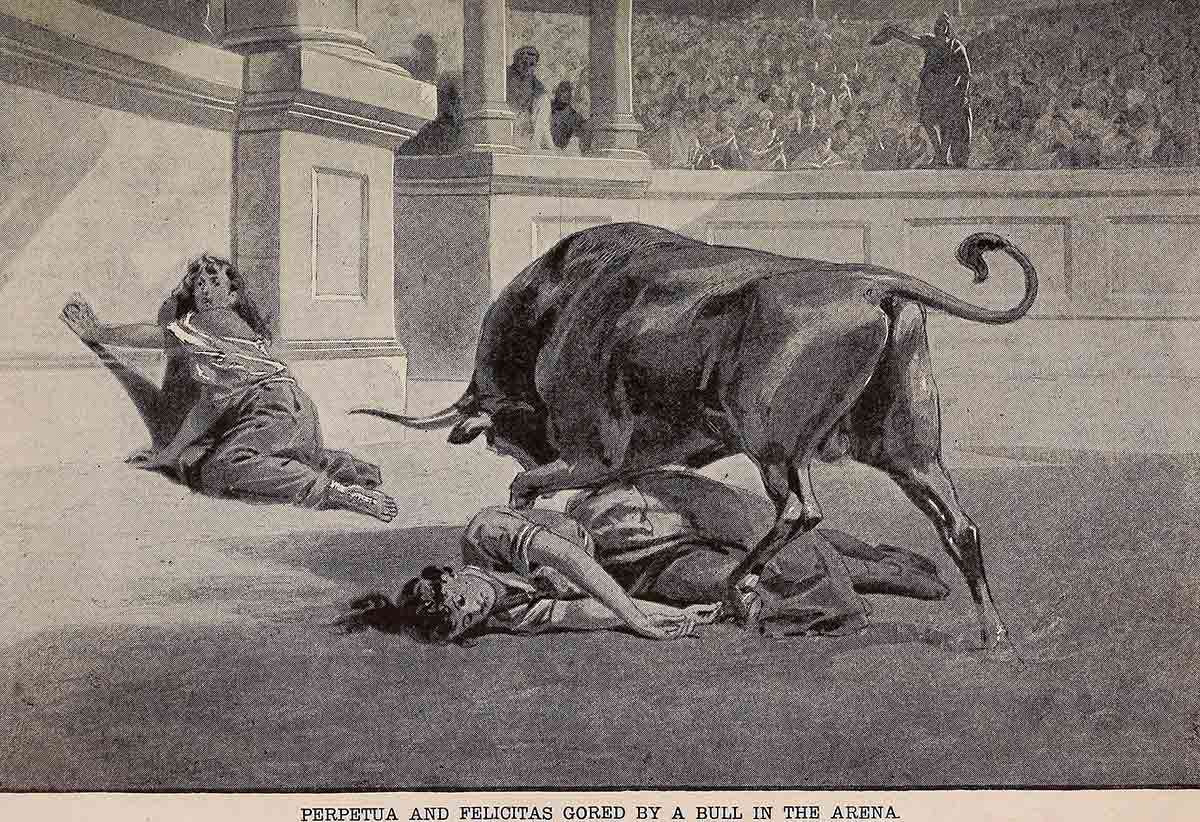

Felicity gave birth to a daughter in prison. This was said to give her great joy because the Romans did not execute pregnant women, and she wanted to die with her friends. The editor noted that they all entered the arena with joy, not fear, on their faces. Felicity and Perpetua faced an enraged heifer; the sex of the animal was chosen to match the sex of the martyrs. The animal wounded Perpetua, but it did not kill her.

A gladiator was ordered to execute her with his sword. However, he was young and inexperienced and, in the end, Perpetua took his hand and guided it to her throat so that he could kill her cleanly. Of the men, Secundulus died in prison and was spared the ordeal of the arena. Satarininus and Revocatus faced a leopard and a bear and died. Saturus fought a leopard that bit him. He survived that, but his life ended when a gladiator slit his throat.

Conclusion

The Passion of the Saints Perpetua and Felicity is significant on several levels. For the Christians of that day, as well as Christians down through the centuries who have faced persecution and martyrdom, it has been both an encouragement and a comfort as they attempt to imitate the martyrs in their faith and in their courage.

Perpetua’s story represents an example of a woman who did not bow to the men in her life, but chose her own path in a society in which women had little power and no public voice. The Montanist sect elevated the status of women, recognizing their gifts and placing them in leadership positions, reflecting the Biblical statement that “there is no male or female; all are one in Christ” (Galatians 3:28).

For scholars, the diary gives them a glimpse of what life was like for Christians under the rule of the Roman Empire in the early years of the 3rd century. It was a time when being a Christian was neither safe nor easy, as the martyrdom of Vibia Perpetua reveals.