The start of the Viking Age is usually dated to the end of the 8th century when the Vikings attacked Lindisfarne and began raiding the British Isles. However, new archaeological evidence suggests that the start of the Viking Age should probably be pushed back 50-100 years. Viking boats discovered at Salme on the island of Saaremaa in Estonia suggest that the Vikings were actively raiding and settling the Baltics from the late 7th century.

Redefining Viking History in the Baltics

Our understanding of Viking history in the Baltics expanded significantly in the early 21st century when, in 2008, archaeologists discovered the remains of a ship at Salme on the island of Saaremaa. While they initially thought they had found a relic from World War II, it was later revealed as a Viking ship. Two years later, a second, larger ship was discovered just 100 feet away. Archaeologists believe there may be one more yet undiscovered ship in the vicinity.

The first ship was 11.5 meters (37.7 feet) long and two meters (6.5 feet) wide and contained the remains of six bodies. The second ship was 17 meters (55 feet) long and three meters (10 feet) wide and contained the remains of 33 bodies. The ships themselves were completely rotted. They were reconstructed from discoloration caused by the wood, plus 275 surviving iron rivets for the first ship, and more than 1,200 surviving nails and rivets for the second ship.

Archaeological remains and DNA analysis suggest that all 39 bodies were male and that they and the ships came from Sweden. Radiocarbon dating places ship construction sometime between 650-700 CE. Signs of repair, patching, and continuous use suggest that they may have been on the water for 50 years, finding their final resting place between 700-750 CE.

The remains also suggest that the ships used sails, pushing back the date for this technology, both among the Vikings and in the Baltic region. This would explain how these ships could navigate the 100 miles of open water between Sweden and Estonia. This find also suggests that the Vikings were using their superior ship technology to dominate their neighbors 50-100 years before they started raiding the British Isles. So, what was happening in Sweden at this time that would explain this early Viking activity in the Baltic?

The Ynglinga Saga: Mythical Kings of Sweden

The Christian Icelandic author Snorri Sturluson wrote his Ynglinga Saga in the 12th century CE. It is believed to be based on a 9th-century Skaldic poem called Ynglingatal, which Sturluson quotes frequently. The saga claims to tell the history of the earliest Swedish kings, but until recently, it was mostly thought to contain legend and myth.

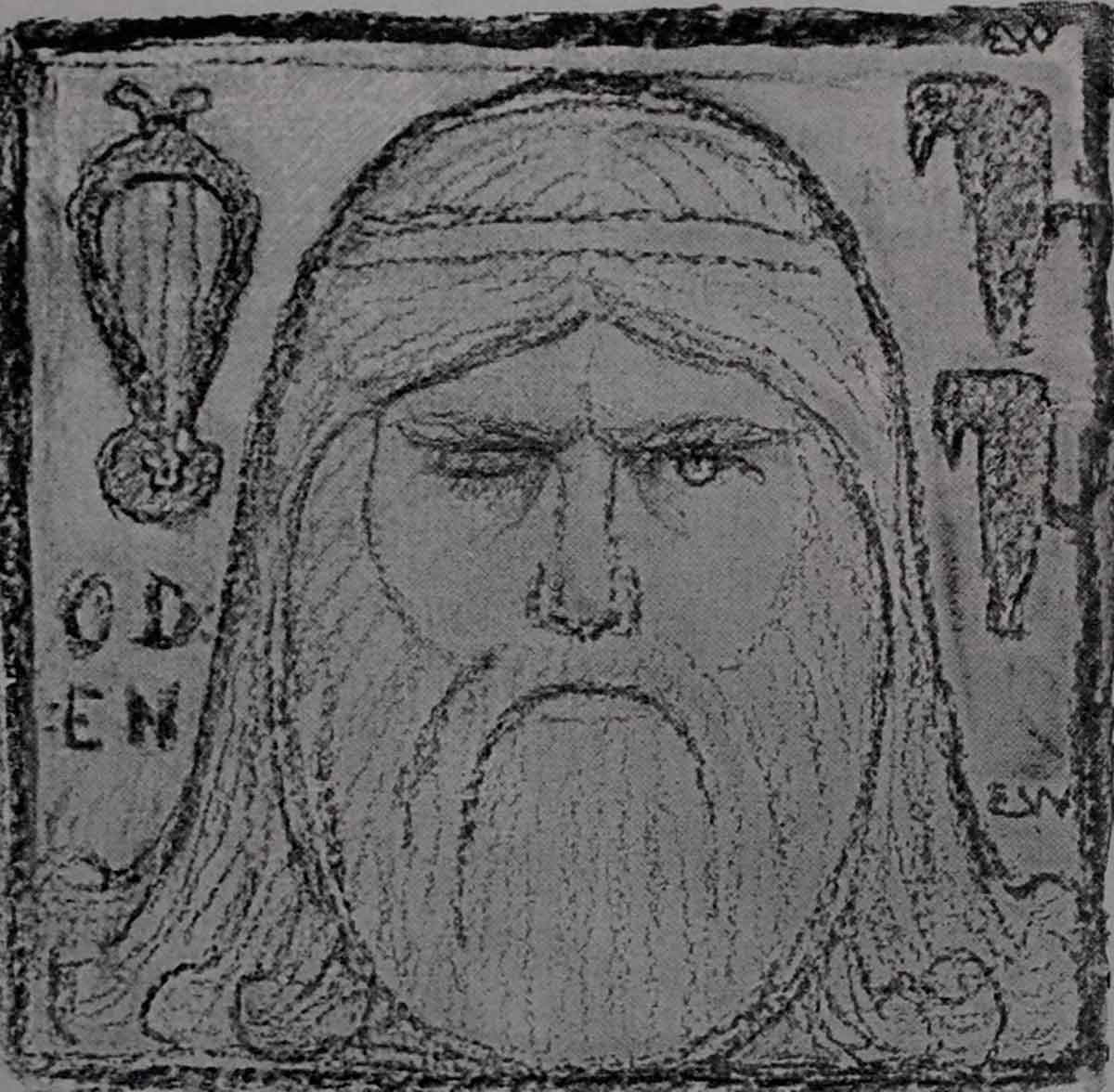

The work starts by retelling the story of the divine Aesir-Vanir War, with Odin and the other gods transformed into ancient rulers of a great land. Odin hears of the fertile lands in Scandinavia and leaves his capital, Asgard in Asaland, to create a new settlement in what would become known as Sweden, introducing the laws and customs of Asaland.

Odin was succeeded by Njord, a Vanir who went to live among the Aesir after the conclusion of the Aesir-Vanir War. After many years of prosperity, during which all the ancient ones died, bringing their age to an end, Njord also died and was succeeded by his son, Freyr. Also known as Yngvi, Freyr established Uppsala as the capital of his kingdom and started the Ynglinger Dynasty.

There follows a list of around 30 kings with unbelievably long reigns and incredulously heroic stories, including Ragnar Lodbrok and Bjorn Ironside. While both these figures probably existed, their place in the Ynglinga Saga’s list seems historically inaccurate, making them more legendary than historical in this context. Scholars have always assumed that the same was true for the other kings on the list until the reign of Erik the Victorious, a 10th-century ruler known to be historical.

King Ingvar Harra of Sweden

One of the early kings on the list is Ingvar Harra, who reportedly reigned several generations before Ragnar Lodbrok, probably near the start of the 8th century CE. According to the saga, he spent much of his time patrolling the shores of Sweden to protect them against Danish Vikings and Estonian pirates from the Baltic. He eventually made a treaty with the Danes to focus his resources on dealing with the Estonian threat.

One summer, he sailed to Estonia, to either attack or negotiate with the Estonians. When he arrived, they had assembled a great army to meet him. In the ensuing battle, Ingvar was killed, and his men were forced to retreat. According to the saga, Ingvar was buried in Estonia on the shores of Adalsysla in mainland Estonia.

But Snorri Sturluson also quotes a 9th-century poem about the death of Ingvar in Estonia that says that he was buried on an island in the heart of the Baltic where the sea sings songs of the sea giant Gymir to delight the Swedish ruler. The Historia Norwegiae, a history written in Latin by an anonymous monk in the 13th century, also says that Ingvar was buried on an island in the Baltic called Eysysla, an Old Norse name for the island of Saaremaa. Can the ships found on Saaremaa be linked back to Ingvar and his story?

Viking Warriors in Estonia

The 39 men found on the two ships at Salme have been identified as Viking warriors. Examination suggests that they were all men between 18 and 45 years old. Many showed signs of healed wounds, suggesting they were veterans of several battles. They also appear to have been a tough and imposing group. The average height of the men was five feet and ten inches, and a few of the bodies were over six feet tall. They would have towered over the 8th-century English, who were only around five feet and five inches tall on average.

DNA analysis also suggests that four of the men were brothers and had a close familial relation to another man on the boat, perhaps an uncle. It seems raiding was a family affair.

But while this may have been an impressive band of veteran warriors, their raid was unsuccessful, as these ships became their graves. It is worth noting that these ships predate the first known Viking ship burial from Scandinavia by around 100 years.

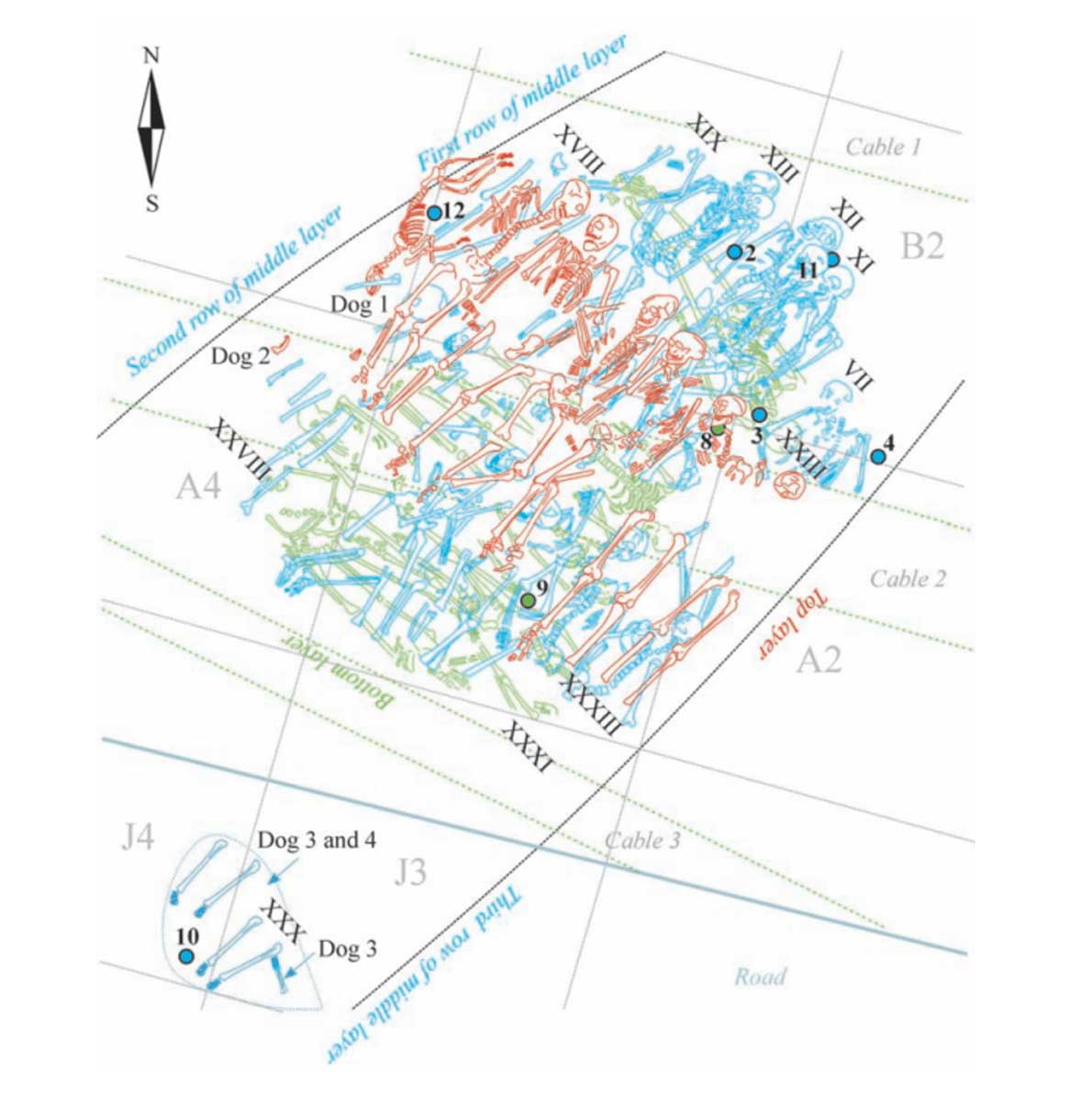

The largest of the two ships is a mass grave. The bodies of 33 warriors were neatly lined up in four layers and covered with a dome of shields, which acted as a shroud. The men were buried with grave goods, which may have been on their person when they died, but also seems to represent selection. They were buried with their weapons and personal items such as combs, but also gaming pieces. More than 100 gaming pieces were found among the bodies.

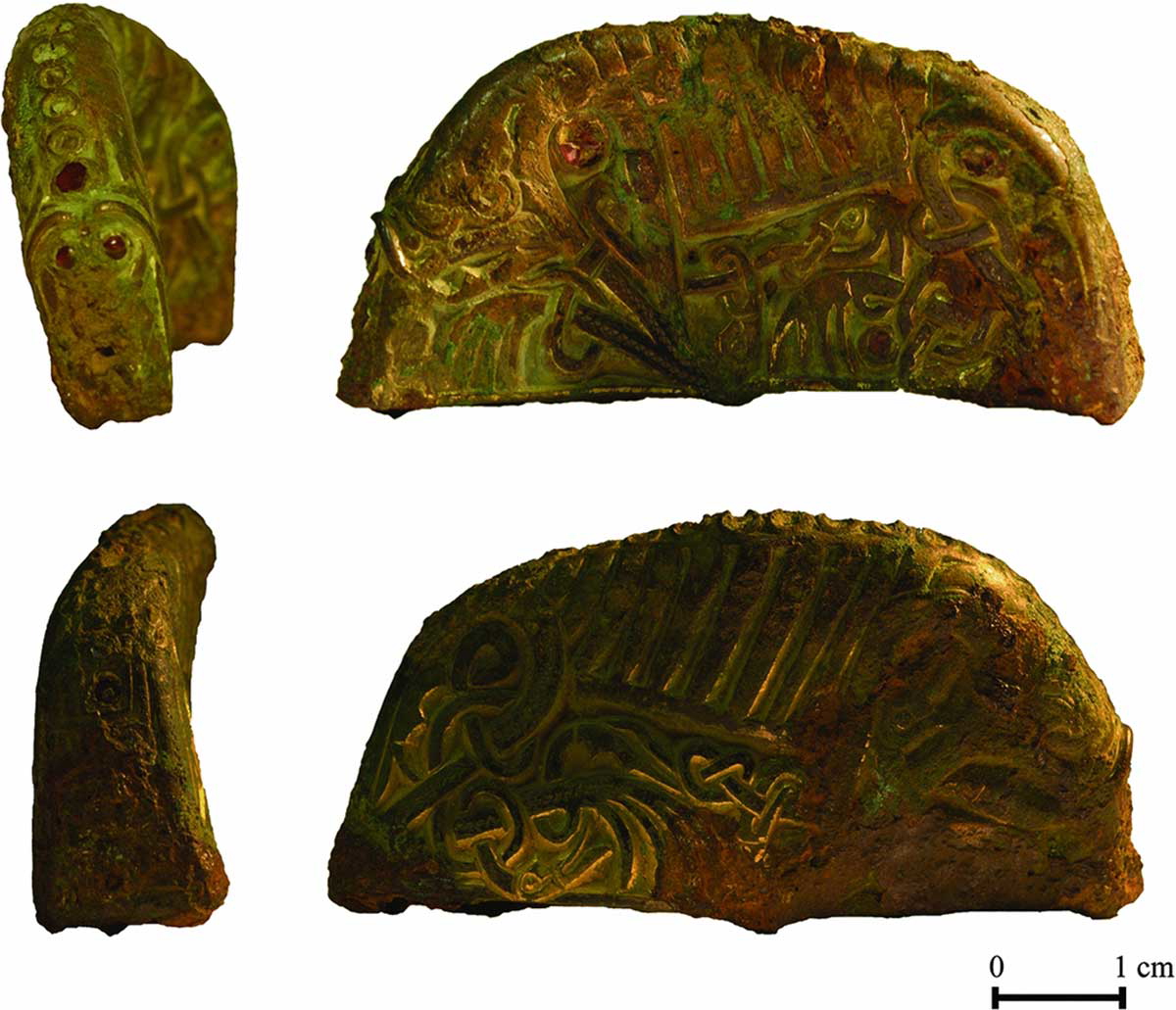

The bodies also seem to have been arranged according to a hierarchy, with the highest ranking on top as they have the best quality weapons and armor. At the very top was a man with the finest blade on the ship, which had a jeweled hilt. He also had a walrus ivory game piece, a king, placed in his mouth. This may have been meant to mark him out as the group’s leader.

The six bodies on the smaller ship tell a very different story. Rather than being organized and laid to rest with care, they were found seated individually or in pairs, slumped over, as if they just died wherever they sat. So, what happened to this party of warriors?

Ingvar and His Men?

These two ships clearly carried warriors from Sweden to Estonia, perhaps as part of a larger fleet. They were involved in a battle, as evidenced by numerous arrowheads found embedded in the ships, including three-pointed types used to set ships alight. At some point, they seem to have pulled the ships ashore on the island of Saaremaa, probably to form a defensive perimeter and make a last stand. Wounds identified on some of the bodies suggest that they died in hand-to-hand combat.

When the battle was over, there were 33 dead and six survivors. The survivors arranged for the burial of their comrades, and clearly considered a boat an appropriate resting place, rather than taking them out and burying them on land. This pushes back the date for Viking ship burials by about a century.

The survivors probably believed that their brave brothers had earned themselves a place in Valhalla, the afterlife for brave warriors who die in battle and that their ship would carry them into the afterlife. The survivors were not so lucky. As they waited to die of starvation and exposure, they knew that they would not be chosen for Valhalla. Over time, both ships were covered by sand and vegetation and forgotten only to be rediscovered more than 1,000 years later.

Could these ships have belonged to King Ingvar Harr and his men? Is the man on the top of the burial pile with the king gaming piece in his mouth Ingvar? Is this the island where legend says that the Swedish king was laid to rest in Estonia? There is insufficient surviving evidence to confirm any of these speculations, but the timeline fits. But even if this is not Ingvar and his men, these ships demonstrate that the Vikings were active in the Baltic at least 50-100 years before they started raiding the British Isles.

The Vikings in the Baltic

While the Salme ships point to the start of Viking activity in the Baltic, it is only the beginning of a long story. From the 8th century, it is possible to see significant Viking influence in the Baltic, with Viking culture influencing local jewelry, weapons, ships, and settlements. Often, archaeological finds in Estonia are identified as imports from the Viking world, but they were equally likely to have been made locally in response to Viking cultural influence.

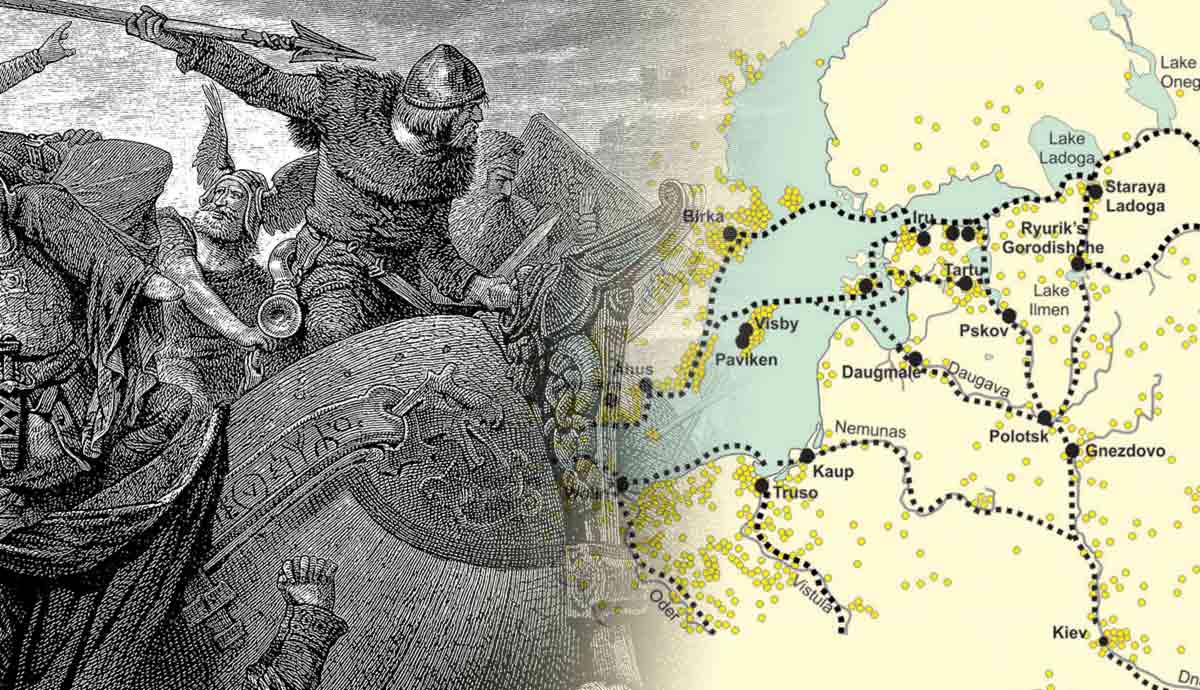

Viking activity in the Baltic was driven by Austrvegr, which means the “eastern way,” with the Baltic Sea becoming a key trading route. The Swedish Vikings traveled to Novgorod and Kyiv in the Russia-Ukraine region, kingdoms reportedly founded by Swedish Vikings, Constantinople in the Byzantine Empire where Swedes often served in the Varangian Guard, and even Baghdad in the Arab world. Many Arab dirham coins made their way back to Sweden.

By the 10th century, Estonia seems to have become part of the Viking world. Many stories mention Viking activity in the region. For example, in the story of the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason, in the late 10th century he was kidnapped and enslaved by Vikings from Estonia, until he was spotted at an Estonian slave market, freed, and taken to Novgorod. Njals Saga reports a battle between Estonians and Icelandic Vikings off the coast of Saaremaa in the Baltic in 972 CE.