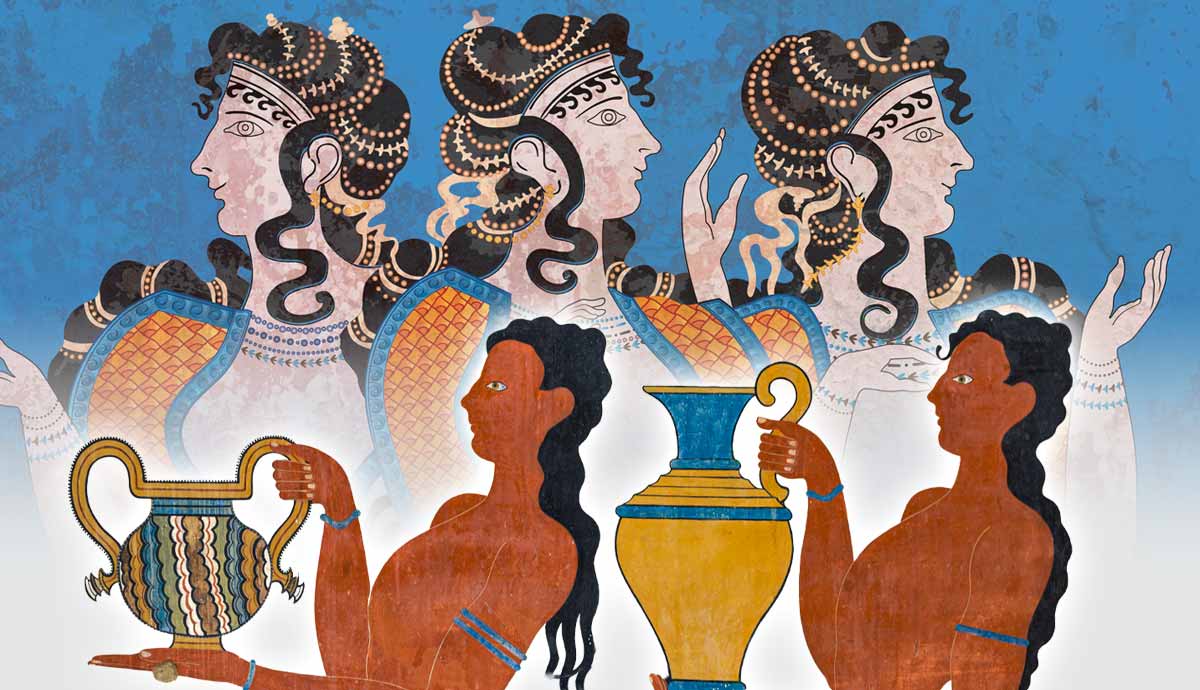

Throughout most of the Bronze Age, the Minoans ruled over ancient Crete and several other islands in the Aegean Sea. They also had colonies in Anatolia, the Levant, and perhaps even Libya. All the evidence shows that they were a rich, comfortable, and relatively advanced civilization. Yet, that all changed at some point during the Bronze Age. The Mycenaean Greeks overthrew the Minoans on Crete and put an end to their trading empire. But when their civilization and power network collapsed, what happened to the Minoan people?

How Did the Mighty Minoans Die?

In the 16th century BCE, the volcanic island of Thera erupted. This was one of the largest volcanic eruptions in all of human history. There was a prominent Minoan colony on that island, but it seems that few, if any, Minoans there actually died in the eruption. They evidently evacuated the island before it happened.

Nevertheless, this eruption completely destroyed this important, strategically placed colony and caused a tsunami which struck the north coast of Crete. While not crippling the Minoans, the archaeological evidence shows that they soon became far more concerned with fortifying their settlements and creating storage spaces than they had been prior to the eruption. At this same time, Late Minoan IB, the Minoan colony on Kythera just next to Greece, was destroyed. All of this evidence indicates that the Theran eruption led to a period of conflict between the Minoans and the Mycenaeans.

After this, at the end of Late Minoan IB stage (around 1470-1450 BCE), we see widespread destruction all over Crete. Virtually all the major power centers with their palace complexes were destroyed in what were clearly targeted attacks. Immediately after this, the language of the administrative tablets changed from Linear A (the script of the Minoans) to Linear B (the script of the Mycenaeans). Furthermore, Mycenaean material culture characterizes Crete after Late Minoan IB. This evidence strongly indicates—although not all scholars agree—that the Mycenaeans invaded and conquered Crete.

However, was this when the Minoans died? No, the Minoan civilization continued for centuries thereafter. Nevertheless, the Minoans were being slowly but surely absorbed by the Greeks who had come to dominate the island. The final phase of Minoan history is often given as Late Minoan III, which ended in c. 1075 BCE. After this, according to many modern sources, the Minoans died as a distinct ethnic group. However, archaeologists have noted something very interesting and important in the final part of Late Minoan III which—together with other evidence—refutes that conclusion.

The Minoan Refugee Settlement

During Late Minoan IIIB and C, most of the Minoan cities across eastern Crete were abandoned. This represents the era in which most of the Minoans either died or were absorbed by the Greeks. What happened after this? In these two phases of Minoan history, archaeologists have found evidence for extensive Minoan activity in the region of Praisos, which is in the easternmost part of Crete.

One of the most striking finds is a large settlement. The walls of this settlement were built in the style of the Minoans, and we also find Minoan tombs in the area. This large settlement dates to Late Minoan IIIC, with other, more minor evidence of Minoan activity in the preceding Late Minoan IIIB. Therefore, it appears that the Minoans arrived here in the 14th century BCE, but only properly built up the settlement after 1200 BCE. Interestingly, this has been described by some archaeologists as a “refugee settlement.”

The Subminoan Period

Despite the idea that Minoan history ended around 1100 BCE, archaeological evidence indicates that the Minoans had not yet died as a distinct ethnic group by that point. In reality, Late Minoan III was directly followed by the Subminoan period. The connection between these two periods is so close that some archaeologists believe that they actually overlapped, with Subminoan I forming part of Late Minoan IIIC. In any case, Subminoan II definitely came later. Some scholars believe that this continued until as late as c. 970 BCE.

This suggests that the Minoans continued to exist as a distinct ethnic group until as late as the 10th century BCE. On the other hand, we have to be cautious about treating pottery styles as synonymous with ethnic groups. Nevertheless, as we look further forward in history, there is evidence which appears to validate this understanding of the nature of Subminoan pottery.

An Enduring Community

After the end of the Subminoan period, the Minoans had indeed mostly died off as a distinct ethnic group—at least as far as a distinct material culture is concerned. However, this does not mean that all traces of them disappeared. Even long after the Bronze Age collapse, there is evidence of a distinct group on Crete which can be identified as the descendants of the Minoans.

At the apparent Minoan refugee settlement near Praisos, there is evidence for continued habitation until c. 900 BCE. This is after the end of the Subminoan period, yet as we saw, the settlement was clearly established and inhabited by Minoan survivors. Therefore, this indicates that a distinct Minoan material culture disappeared after c. 970 BCE, even though at least one distinct community of Minoans remained in existence until the end of that century. Not long after this, we find evidence for interesting activity at Praisos.

The Eteocretans of Praisos

Three fascinating inscriptions have been found at Praisos. The earliest dates to the late 7th or the early 6th century BCE. The second dates to about the 4th century BCE, while the third dates to the following century. Another relevant inscription was found at Dreros, some distance from Praisos, but also on the eastern part of Crete. What do all these inscriptions have in common?

Although written using the Greek alphabet, they were written in a non-Greek language. In fact, they were written in a language which does not seem to be related to any other known tongue. Many scholars believe this to be the same language that was used by the Minoans, which is equally undeciphered. Most of the Minoans had died by this point. Yet, this would indicate that there continued to exist a community, or communities, in eastern Crete that spoke a distinct language, quite possibly the language of the Minoans.

Further supporting evidence for this is the fact that ancient written sources strongly suggest that the speakers of this language were known as the Eteocretans. For example, Homer’s Odyssey, written in the 7th century BCE, refers to the Eteocretans as one of the groups inhabiting Crete. Strabo, in the 1st century BCE, also mentioned them. Strabo included the significant detail that the Eteocretans were particularly associated with the region of Praisos on Crete. Furthermore, he made a point of describing them as the native inhabitants of the island.

This being so, they were evidently not Greek. Since they were said to have lived at Praisos, this leads to the obvious conclusion that the non-Greek inscriptions in that very area were written by the Eteocretans. What does this mean for the Minoans? Put simply, this evidence indicates that some Minoans actually survived as a distinct language-speaking group in eastern Crete long after the Bronze Age, after most of the Minoans had died.

What Happened to the Minoans After the Fall of the Civilization?

So, what happened to the Minoans after the fall of their civilization? While they were conquered by the Mycenaeans and their settlements disrupted, they did not completely die off, and nor were they completely absorbed into the new dominant Greek society. Archaeological evidence suggests that a distinct Minoan community survived near Praisos on the eastern part of Crete until as late as the 10th century BCE. The “refugee settlement” in that area was abandoned in c. 900 BCE, but even then, written evidence suggests that the descendants of the Minoans preserved their language and, by necessity, a distinct identity. They had become the Eteocretans, where the Greeks remembered them as Crete’s original inhabitants.