The Desert Fathers appeared on the Christian historical scene in the third century CE. Saint Anthony is often considered the most notable among them, though he was not the first. The Desert Fathers were committed and dedicated believers who chose an ascetic lifestyle that would express their earnest beliefs. They decided not to associate with the mediocrity and compromise that entered Christianity when it became the Roman State religion. Other believers began to seek out these holy men to draw on their wisdom and many embraced the lifestyle the Desert Fathers chose.

Rise of the Desert Fathers

For the first couple of centuries of the common era, Christians were persecuted and often killed for their faith. There was no such thing as a nominal Christian. Being a Christian was a matter of life and death. As the number of Christians rapidly grew, despite the struggles they faced, change inevitably came.

In 313 CE, with the Edict of Milan, Emperor Constantine declared Christianity the state religion. The persecution of Christians was over. There was, however, a negative side to this change. Nominal Christianity sprang up. Instead of radical dedication to the principles of their faith, many who claimed to be Christians now compromised and made accommodations for lifestyles and actions Christians previously never engaged in. Mediocrity set in and many called themselves Christian for the benefits it held for their social standing.

Those who were Christian to the core and held to their principles wished to separate themselves from the worldly form of Christianity that became prevalent in cities. Unlike previous generations who at times fled to the desert to escape persecution, these believers withdrew to more remote areas such as the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria to escape compromised Christianity. In the deserts they could dedicate themselves to God and in seclusion, they could search for divine guidance and wisdom to guide their lives. These individuals would become hermits, preferring an ascetic lifestyle over the watered-down Christianity practiced in populated areas.

Ironically, many Christians from the city would come to the deserted places the Desert Fathers chose to reside in, in search of their wisdom and divine insight. Many were inspired by what they saw, and, in time, communities of desert-dwelling Christians developed that would rival the populations of some towns.

Paul of Thebes

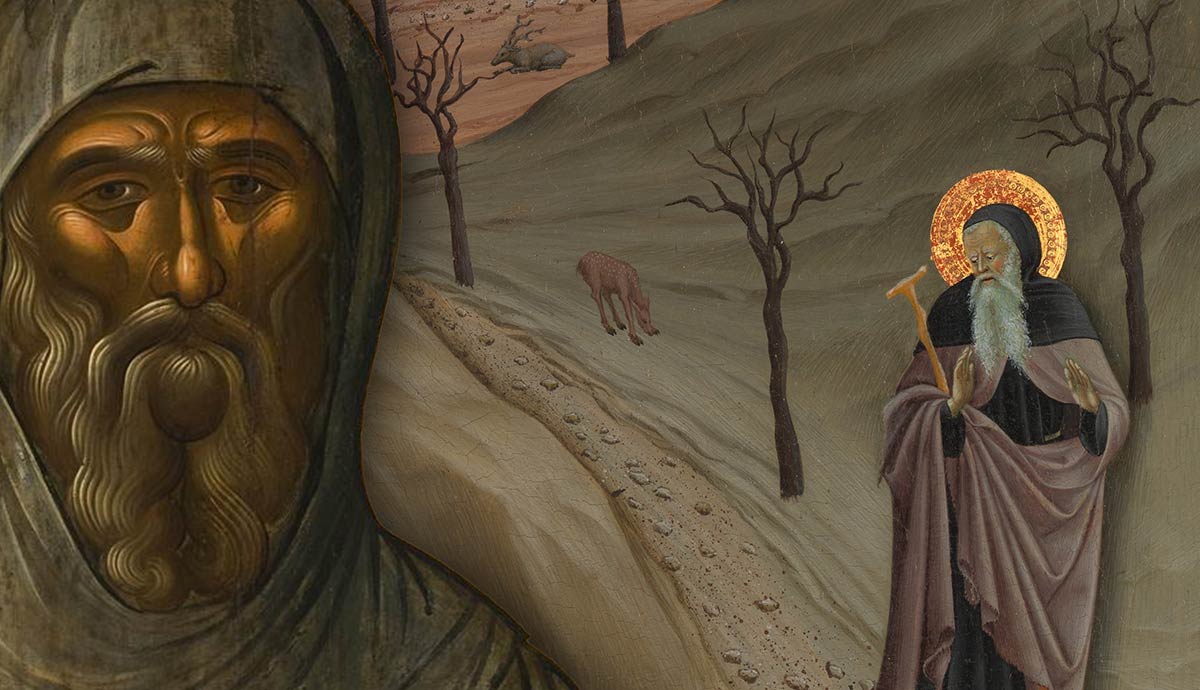

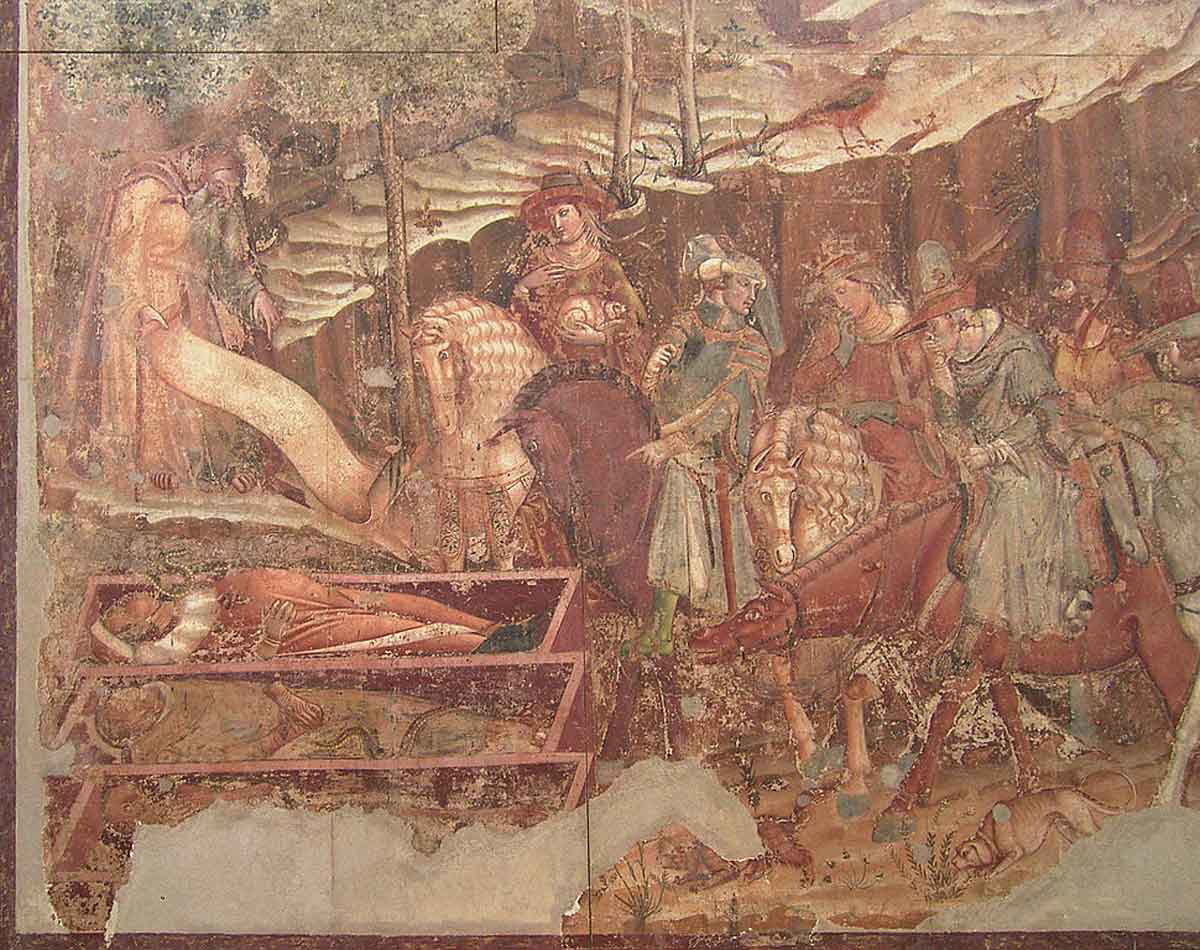

Though many consider Anthony the father of Monasticism, the impact Paul of Thebes had on Anthony is undeniable. Paul of Thebes, like many Christians of the 3rd century, had to flee persecution by the authorities of the day. His parents had passed away and his brother-in-law saw the opportunity to gain Paul’s inheritance by betraying the 16-year-old boy to the persecutors. At the time, Christians suffered persecution under the Roman emperor Decius. Paul fled to the desert around Thebes in Egypt and found a cave in the mountains where he could find shelter and hide. He soon came to consider the lifestyle he was forced into as a blessing.

For many years Paul was sustained by the fruit of a palm tree and a freshwater spring in the vicinity. Later, a raven provided Paul with bread daily. He dedicated his life to prayer and penitence, remaining true to his faith despite his circumstances. Jerome described Paul of Thebes as the first Christian hermit. Paul reportedly lived to be 113 years old, residing in the desert for almost 100 years. In the last year of his life Paul and Anthony’s paths crossed, and Anthony laid Paul to rest after his death.

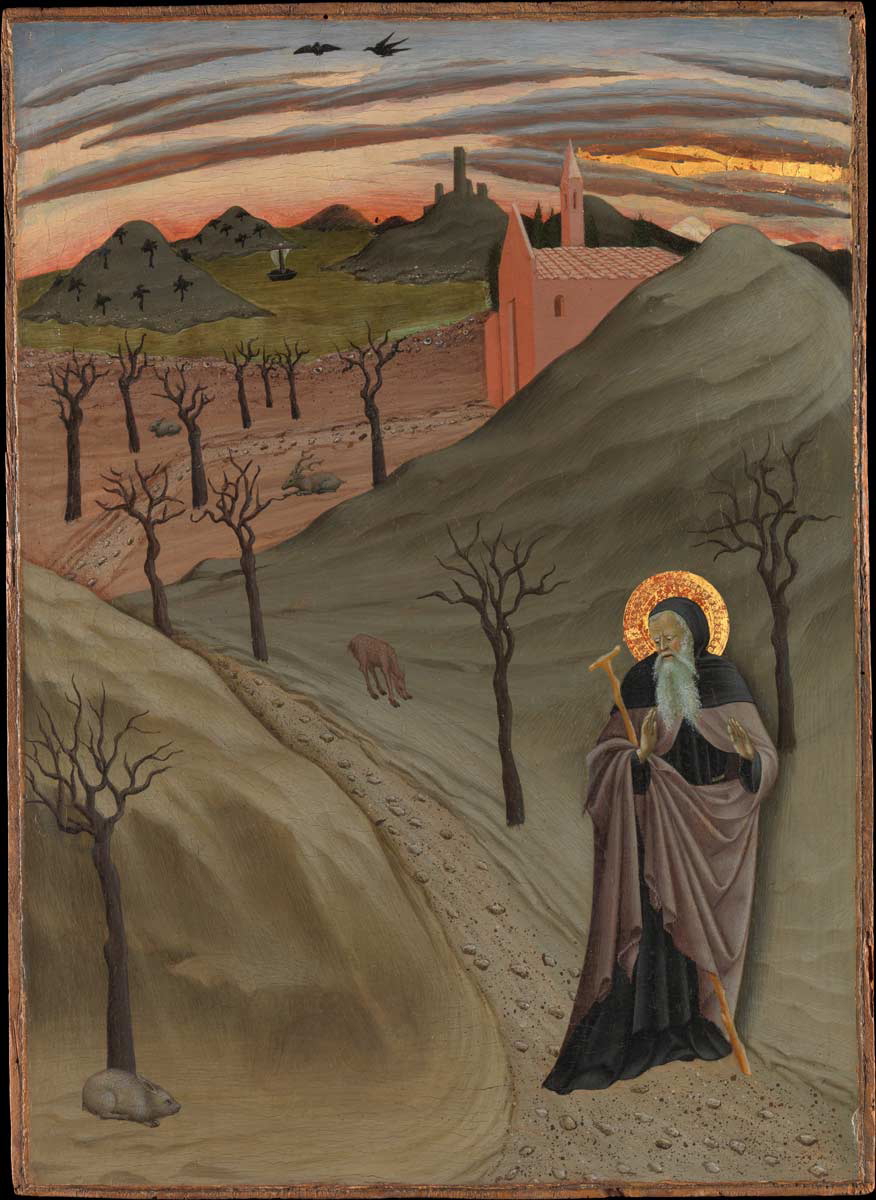

Anthony of Egypt

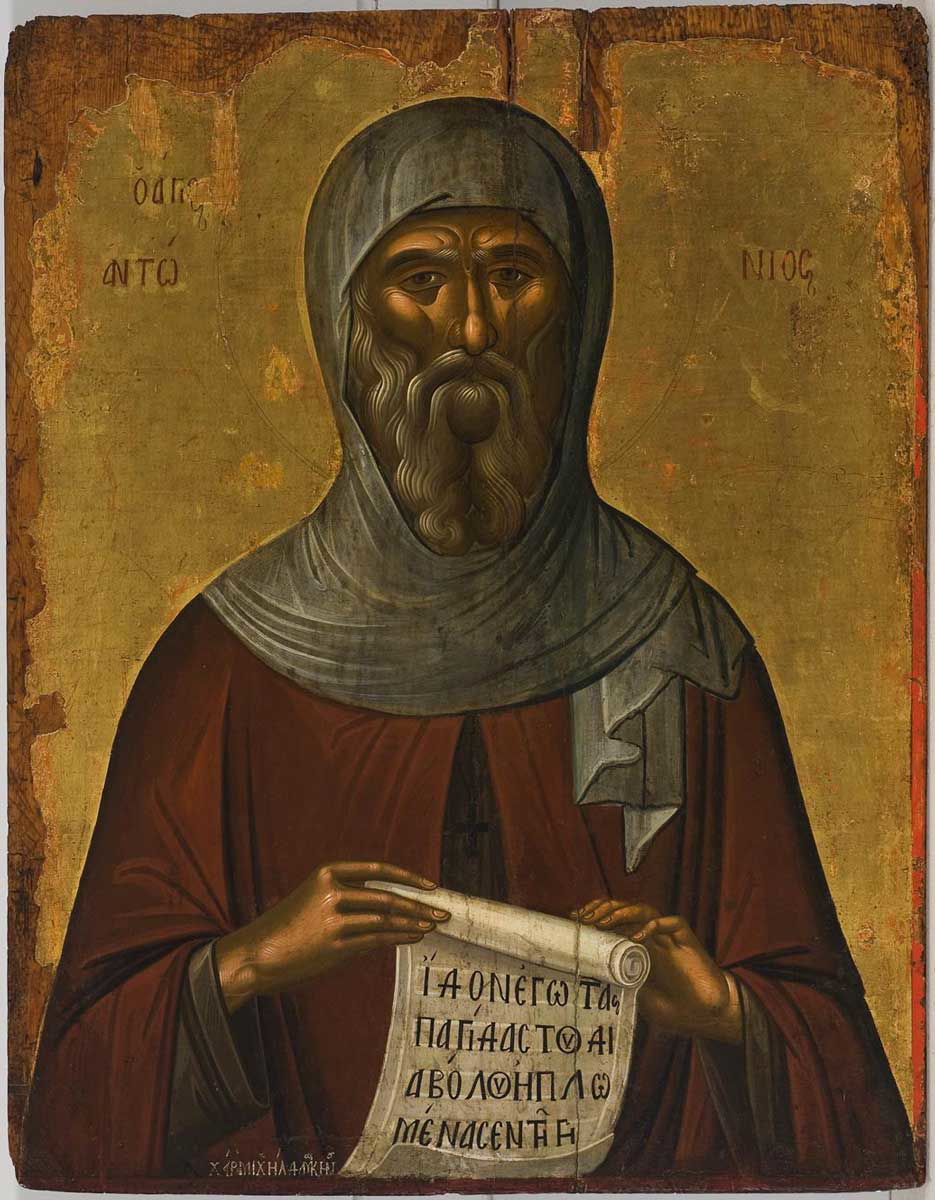

Anthony’s path to the desert was different from that of Paul, though they shared many similar life experiences. Anthony was born to a well-to-do Christian family in Coma, Egypt in 251 CE. When he was about 20 years of age, he inherited considerable wealth when his parents passed away. One of his responsibilities was to take care of his sister. Anthony was always looking for the best way to live his life to the glory of God.

One day, the words of Matthew 19:21 impressed on Anthony in a life-changing way:

“Jesus said to him, ‘If you would be perfect, go, sell what you possess and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.’”

Anthony promptly sold what he owned and gave the proceeds to the poor. He left his sister with a community of consecrated virgins, similar to what later would be called a convent. This way, Anthony met his commitment to his family in a way that allowed him to engage on his journey into asceticism.

Initially, Anthony resided in a hut on the outskirts of his hometown under the tutelage of an elder who acted as his spiritual guide. Once he felt comfortable to continue his journey on his own, he left the hut and moved farther away, making an empty grave his home to remind him of his mortality.

During the two decades he lived there, Anthony experienced many attacks from demons appearing as wild beasts such as leopards, lions, bears, scorpions, and wolves set on harming him. God protected Anthony through these onslaughts which made Anthony stronger in faith and wisdom.

Anthony withdrew farther still, seeking solitude, but others sought him out to learn from him and follow his teachings. He became a notable teacher and resided in the desert for many decades. At the age of about 90, Anthony wondered if he was the person who lived the most ascetic life. By divine revelation, he found out about Paul of Thebes and decided to find a hermit.

According to Jerome, Paul and Anthony met and shared a meal of bread together which a raven provided. The two hermits shared much in common and they prayed and spoke together for the time they had. Paul passed away soon after their meeting, in Anthony’s presence.

Legend holds that Anthony buried Paul with the assistance of two lions who dug the grave. The providence of Anthony’s presence at Paul’s death symbolizes the continuity of the ascetic tradition. Anthony popularized ascetic living and founded several ascetic communities. For this reason, scholars rightly consider him the father of monasticism.

Anthony had a great influence on cenobitism or communal monasticism. His disciple, Pachomius, contributed to formalizing communal monastic life and learned much from his mentor on the subject. He set rules in place to guide the functioning of communal monasteries, which included communal worship, shared work such as farming or manual labor, and strict routines that demanded much discipline.

Other Desert Fathers

Macarius the Great, also known as Macarius of Egypt, contributed to the tradition by teaching inner purity, the struggle against demonic temptations, and continuous prayer—practices that would become central to later Christian mysticism.

Evagrius Ponticus, who studied under Basil and Gregory Nazianzus, wrote much on spiritual living after joining the ranks of the Desert Fathers. He developed the idea of the “Eight Evil Thoughts,” which represented things monks and ascetics had to overcome. These were gluttony, lust, greed, sadness, anger, acedia (spiritual laziness), vainglory, and pride.

Arsenius the Great had the honor and prestige of being a tutor to emperors. Yet, he set aside the prestigious life to embrace that of a hermit living in the desert. He became known for his wisdom and was revered among the Desert Fathers for his strict ascetic practices.

Moses the Black, also known as Moses the Ethiopian, transformed from robber to Desert Father after a powerful testimony of repentance and transformation. He became a leader in his monastic community.

There were many other Desert Fathers who each contributed to monastic living and wisdom in a significant way. A collection of their wisdom was compiled in the Apophthegmata Patrum, or “Sayings of the Desert Fathers” and served as a testimony to their lifestyle of commitment to God. These sayings are timeless nuggets of insight into spiritual matters that demonstrate the contribution the Desert Fathers made to Christianity.

Desert Mothers

It was not only men who sought spiritual enlightenment through asceticism. There were also Desert Mothers who lived at the same time as the Desert Fathers and they had no less disciplined lifestyles than their male counterparts. These communities of Desert Mothers had the same goals as that of the Desert Fathers, though much less has been recorded about them.

Some of the most notable Desert Mothers were Syncletica of Alexandria, Sarah of the Desert, Theodora of Alexandria, Melania the Elder, Melania the Younger, and Olympias the Younger. Their dedication and commitment were in every way equal to that of their male counterparts.

The Desert Fathers (and Mothers) serve as examples to contemporary Christians of dedication and commitment to holy living. Their wisdom has unfortunately gone largely unread in modern times and is undervalued, though it is as valuable today as it has been in any era since it was written.