By the end of the Black War in 1832, Aboriginal men, women, and children in the Settled Districts had either been killed, imprisoned, or captured. The authorities were faced with a crucial question: what should be done with the survivors? They ultimately decided to deport them to Flinders Island, a large island in the Bass Strait, northeast of Tasmania, to a designated place called the Wybalenna Aboriginal Settlement. Wybalenna was eventually abandoned due to its poor health standards and the survivors were relocated to Oyster Cove, the second death trap in the history of Tasmanian “friendly” missions.

The Wybalenna Aboriginal Settlement

The Aboriginal men, women, and children captured during the Black Line and those who had “surrendered” to G.A. Robinson were dispatched to the Wybalenna Aboriginal Settlement on Flinders Island. In October 1835, Robinson himself took up the position of superintendent. Wybalenna represented the basis for assimilation programs across Australia.

As the settlement’s superintendent, Robinson had boys and girls removed from their parents and sent to the Orphan School in Hobart, where they were trained to lead a proper Christian life. Many resented Robinson for this, even with his staunch refusal to use physical violence in the settlement’s administration. Despite Robinson’s promises that Aboriginal people at Wybalenna would see their customs respected, adults were treated like children.

Every morning, they had to await inspection and women were expected to attend sewing classes in the afternoon. Every day, someone ensured that their houses were clean, their mattresses were regularly aired, and their clothes were washed. Wybalenna remains a unique experiment. Despite the settlement’s many flaws, Aboriginal people were “looked after” by an unprecedented number of officials and convicts. Sir George Arthur, the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (as Tasmania was known back then) appointed a surgeon, a catechist, a gardener, as well as four soldiers and a corporal to ensure law and order. Their families followed.

Arthur also appointed six male convicts to build huts and the most basic infrastructures, take care of the veggie gardens and tend the cattle and sheep. Aboriginal people also enjoyed a certain amount of freedom, within the confines of a white-oriented society.

Some Aboriginal families were even allowed to move to the bush outside the main settlement, where they built their huts, performed ceremonies, painted their bodies ochre, and hunted kangaroos and wallabies like their ancestors had done for centuries. However, the situation quickly deteriorated; 29 people died in 1837 alone of gastroenteritis and pneumonia. Among them, there were feared guerrilla leader Tongerlongter (1790-1837), the widow of another warrior, Montpelliata (1790-1836), and Kartiteyer, the son of Mannalargenna (1770-1835), the older leader in the group. These deaths were directly caused by the poor living conditions at Wybalenna, possibly by Escherichia coli bacteria. As people kept falling sick around them, many fled to the bush.

Who Were the Aboriginal Men and Women at Wybalenna?

123 people were initially stationed at Wybalenna. They were divided into three distinct groups led by seven chiefs and came from different clans and nations. The largest group was made of almost 50 people from the North West and South West nations. Truganini (1812-1876), perhaps the most well-known Aboriginal woman from Tasmania, was one of them. The second group comprised more than 30 men and women from the North East, North Midlands, and Ben Lomond nations. The third and smallest encompassed at least 20 members of the Big River and Oyster Bay nations.

Some of them, like Montpelliatta, Tongerlongter, and Mannalargenna, were feared guerrilla leaders who had led a staunch resistance in the Settled Districts beginning in the 1820s. Others maintained friendly but complex relations with Robinson.

Eumarrah (1798-1832), for instance, was reportedly one of Robinson’s most trusted confidants. It has been reported that Eumarrah repeatedly pressured Robinson to promise some guarantee that at Wybalenna his people could finally be independent. However, most of them eventually died on Flinders Island, homesick and depressed, after being given (sometimes willingly) an English name. Tongerlongter, for instance, was assigned the name of King William (he would, ironically, die on the same day as the monarch he was named after, William IV, Queen Victoria’s uncle, on June 20, 1837).

Australian historian Lyndall Ryan notes in her Tasmanian Aborigines that “by renaming some of the chiefs as kings and the young warriors after heroes in recent as well as ancient history, Robinson wanted the Aborigines to believe that their own authority structure was similar to that of the British.”

Their new, British names represented the first step in their much-hoped-for transition from Aboriginal to British culture. The truth is that Aboriginal men and women on Flinders Island were determined to retain their culture and their ancestral practices. They even developed a lingua franca, so that people from different clans could communicate among themselves and with the catechist assigned to Flinders Island, Robert Clark.

In 1839, another outbreak—influenza this time—killed eight people, in addition to the 29 who had died in 1837. Robinson left Wybalenna in April of that same year. Of the 123 Aboriginal men, women, and children on Flinders Island in October 1834, 59 of them had died.

From Wybalenna to Oyster Cove

The situation at Wybalenna continued to deteriorate after Robinson’s departure and the appointment of Scottish medical officer Dr Henry Jeanneret. In 1846, along with seven other men, Walter Arthur (1821-1861), son of Rolepa of the Ben Lomond Tribe from north-eastern Tasmania, drew up a petition to Queen Victoria to complain about Jeanneret’s brutal methods. The petition was received.

James Stephens, the under-secretary of state for the colonies, recommended that the Flinders Island Aboriginal people should be transferred to a new site, preferably in Van Diemen’s Land. Wybalenna was abandoned in 1847 and the survivors were promptly transferred to Oyster Cove. Many believed they were finally going home. The night of their arrival on October 18, 1847, they celebrated with dancing and ceremonies. What they didn’t know was that Oyster Cove was a former convict settlement that had been abandoned because the health conditions were too poor, even for convicts.

Oyster Cove was a death trap, even more so than Flinders Island. Interestingly, while the settlement on Flinders Island was known by the Aboriginal name of Wybalenna (which translates as “Black Man’s House”), the new establishment had only one name, the British one. It was located 35 miles south of Hobart and about 12 miles southwest of Kingston, on the ancestral lands of the Oyster Bay Nation, now entirely belonging to colonists.

The arrivals consisted of 14 men, 23 women, and 10 children. The group was initially satisfied with the station as they could row across to Bruny Island, the ancestral country of the Nuenonne Clan of the South East Nation, to collect shells and mutton-bird eggs, and they could rely on the D’Entrecasteaux Channel for shellfish. The settlement’s main section was located at the mouths of the Little Oyster Cove Creek and Oyster Cove Rivulet.

The second section, an area of little less than 700 hectares, was set apart for Aboriginal people to hunt wallabies, wombats, and possums. Once again, the children (5 boys and 5 girls) were promptly removed from their parents and sent to the Queen’s Orphan Asylum in Hobart. Authorities never considered opening a school at Oyster Cove and their removal deeply affected people at Oyster Cove.

At the end of 1854, seven years after their arrival, only 17 people of the original Oyster Cove community were still alive. In 1859, the number dropped to 14, five men and nine women. Among them were Truganini, William Lanney, Mary Ann Arthur, and her husband Walter George Arthur. Walter Arthur was particularly vocal in demanding better conditions for his people. Eventually, the new governor Sir Henry Fox Young granted him a 3-hectare block of land near Oyster Cove.

Here, Arthur, Mary Ann, Fanny (Mary Ann’s sister), and Tarenootairrer (Mary Ann’s mother, renamed Sarah by Robinson) built their cottage. They even hung a portrait of Queen Victoria in the living room. Lyndall Ryan observes that “like so many other Aboriginal men in his position, he appears to have developed a schizophrenic personality: sometimes he was a resistance leader demanding better conditions for his people; at other times he was a desperate conformist aching for the acceptance of white society. But he was never ‘good enough.’”

Tarenootairrer, an important elder in the Oyster Cove Community, died in 1858. Walter Arthur passed in 1861, as he was rowing back to Oyster Cove from Hobart. He probably fell overboard and his body was never found. William Lanney, the last “full-blood male,” died in 1869.

The Last Survivor of Oyster Cove

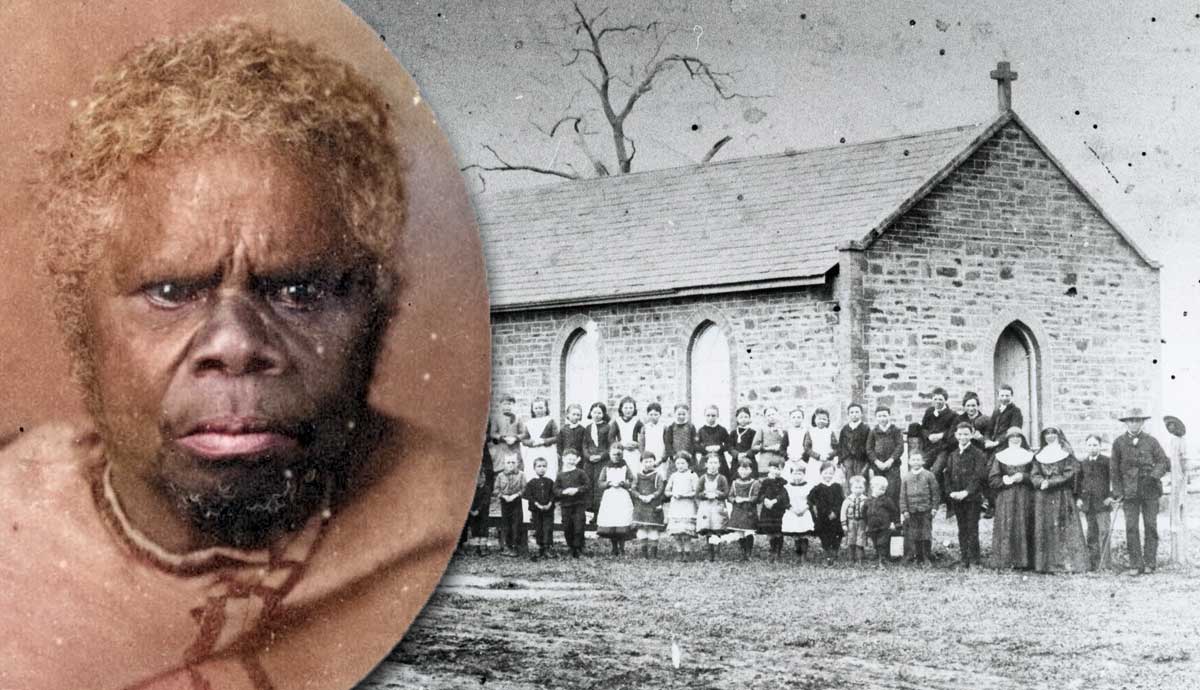

After Lanney’s death, only two women remained at Oyster Cove: Truganini and Mary Ann. Mary Ann died in July 1871, ten years after her husband. For decades, Truganini has been hailed as the “last Aboriginal Tasmanian”, and her death in 1876 was announced as the “death of the last full-blood Tasmanian.” While she was far from the last person of Aboriginal Tasmanian ancestry, she was the last survivor of the so-called Oyster Cove mob.

A member of the Nuenonne Clan of the South East Nation, the Traditional Custodians of Bruny Island, she was born at Recherche Bay in 1812, the daughter of Mangerner, chief of the Lyluequonny clan. The site where the Oyster Cove buildings were established was sacred to the Nuenonne. Truganini lived at Oyster Cove until the winter of 1874 when the mission was heavily flooded.

From 1874 until her death in 1876, she resided in Hobart, in the house of Mrs Dandrige, the wife of the former superintendent at Oyster Cove. She died there, surrounded by her faithful dogs. Oyster Cove closed down in 1874. Little more than 100 years later, in 1981, the government officially proclaimed 30 hectares of Oyster Cove a historic site. In 1984, the Tasmanian Aboriginal community reclaimed it as putalina and the Tasmanian government returned it to them in 1995. Since 1999, it has been an Indigenous Protected Area, managed by the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Rangers.

On December 19, 2013, under the Aboriginal and Dual Naming Policy, six places in Tasmania were assigned Aboriginal and dual names, including Kunanyi / Mount Wellington. As of February 2023, 44 Aboriginal and dual names have been assigned to lakes, bays, rivers, and islands across the island. Tasmania is itself referred to as lutruwita/Tasmania in honor of its Traditional Custodians.