Andrea Mantegna was one of the greatest and most influential artists of the Italian Renaissance. He was unjustly forgotten for several centuries after an unfavorable review from Giorgio Vasari. Today, however, his work is once again valued for its complex symbolism and manipulation of perspective. Read on to learn more about the great Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna and his works.

What Is Andrea Mantegna Best Known For?

Andrea Mantegna was one of the most outstanding masters of Renaissance Italian art. He was born into a carpenter’s family in the Venetian Republic in the early 1430s. At the age of eleven, he became an apprentice to painter Francesco Squarcione. Squarcione was an amateur archaeologist and collector of Greek and Roman antiquities. He allegedly taught Mantegna to manipulate perspective. Mantegna was considered Squarcione’s best student, but he later claimed the master exploited his talent and did not pay him enough.

By the age of 17, Mantegna became an independent artist and, for a decade, worked in his native Padua. As his popularity grew, he was appointed court painter in Mantua, then led by Ludovico III Gonzaga. There, generously financed by Gonzaga, Andrea Mantegna created his most famous and outstanding work.

The forerunner of the discipline of art history, Giorgio Vasari, included Mantegna in his collection of outstanding artists’ biographies yet described him mostly as a copyist of ancient sculptures. He noted that Mantegna’s style of work was more akin to cutting a stone than depicting a living body. Vasari believed that Mantegna’s work lacked liveliness. This attitude led to Mantegna’s partial excursion from art historical narratives for several centuries. The complexity of his symbols, compositions, and intellectual concepts received praise finally in the 20th century. Since that era, Andrea Mantegna has remained an undisputed Renaissance master.

What Technique and Mediums Did He Use?

Like many artists of his time, Mantegna worked extensively with tempera—a mixture of egg yolk and natural pigment. Tempera created a thin, glossy layer of paint that dried so quickly it was impossible to mix it into more complex tones to create a gradual transformation of tone. For that reason, light and shadow in tempera were applied in thin strokes of a small brush in a mosaic-like fashion. However, at the time of Mantegna’s activity, oil paint was already present in the art scene, and he created some of his works with it. Mantegna was also a talented engraver, although the scope of this work is much harder to define as he did not sign his prints in any way.

Mantegna’s figures and scenes had strong lines that gave them almost sculptural qualities, manipulating a sense of grandeur and emotional intensity. A close look at Mantegna’s oeuvre shows that all these aesthetic manipulations were intentional: he never played with his forms just for the sake of playing but rather used them to solve compositional and expressive challenges.

What Were Mantegna’s Most Famous Works?

For more than a decade, Andrea Mantegna worked in Padua, the Renaissance center for science and research, famous for its university. It was there that he learned the basic principles of his art and got familiar with theoretical and symbolic bases. Almost all of his works hide a deep symbolism beneath the painted surfaces or present visual essays on philosophical problems posed by his contemporaries. Like most artists of his time, Mantegna mostly created religious art on Christian subjects. However, he filled it with references to his contemporary era, cultural trends, and even philosophical debates.

1. Saint Jerome in the Wilderness

Saint Jerome is one of the earliest surviving works by Mantegna that gives us a glimpse into his creative process and evolution. He painted it in Padua, which explained the choice of the character. According to the church canon, Saint Jerome abandoned the earthly life of sin and pleasure and isolated himself in the desert, where he translated both the Old and the New Testament into Latin, making them more available to a wider public. Next to him lived a lion. The wild beast allegedly came to him with a thorn in its paw, and Jerome healed the wound. For Christian scholars, Jerome became the symbol of academic and religious devotion and intellect working hand in hand with faith.

2. Adoration of the Shepherds

Adoration of the Shepherds serves as a great illustration of Mantegna’s conceptual and theoretical depth. In the scene of shepherds greeting the newborn Savior, Mantegna included a strangely detailed landscape, with every flower or weed carefully defined. This was far from being simply an aesthetic choice or an exercise in decoration.

In Mantegna’s time, practicing arts and writing poetry on at least some level were prerequisites for any educated higher-class man. In the 15th century, it was debated that poetry was more suitable for depicting nature, as words had more aesthetic and emotional nuance than painting. Thus, Mantegna’s work expressed his opinion on the matter: detailed landscapes and plants expressed the versatility and complexity of painting as a medium.

Another interesting detail is the identity of the commissioner hidden in the painting. Borso d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara, was known for draining the swamps that surrounded his territory. As part of the drainage structures, he often left wicker fences in the area. Such a fence found a place in Mantegna’s painting and linked the work to its owner. It also demonstrated clear inspiration for the Dutch art of that era and might have been Mantegna’s reaction to the latest trend amongst art collectors.

3. Presentation at The Temple

Presentation at The Temple was one of the most famous yet strange works by the Renaissance masters, where he once again demonstrated his unique and sometimes puzzling approach to painted compositions. Mantegna fit all characters—the Virgin Mary, infant Jesus, Saint Simeon, a priest, and a few passersby—into a tight marble frame. Still, the events are not contained in the frame, as infant Jesus’s feet and his mother’s elbow reach over it. All figures are zoomed in and loom almost uncomfortably close to the viewer. This compositional decision immersed the audience into the unfolding events, forcing them to take part in the scene under the watchful eye of Saint Simeon. The saint seems grim, as if he already knows the fate of the child next to him.

The two figures without halos shown in the background most likely represented Mantegna and his wife Nicolosia, the daughter of Jacopo Bellini, one of the founding fathers of the Renaissance painting style. Unlike most other works by the artist, this particular panel was not for sale and was intended for the artist’s home. Possibly, Mantegna painted it after the birth of his first son.

4. Saint Sebastian

Andrea Mantegna painted several similar images of Saint Sebastian during his career. This character was not just his personal preference: according to the Italian tradition of the time, Sebastian was the saint who protected cities and households from plague. The disease was equated to arrows piercing Sebastian without causing him any harm. Similarly, his image was supposed to ward off the tragedy. Mantegna lived through several episodes of plague epidemics during his time and even contracted the disease once, making a difficult recovery.

Two paintings from the Saint Sebastian series had elaborate architectural elements and cityscapes in their backgrounds. Mantegna deliberately painted the figure from a low perspective to make the figure of the saint and the scene appear more impressive and dramatic. Curiously, one of Sebastian’s executors on the painting has the face of Mantegna himself.

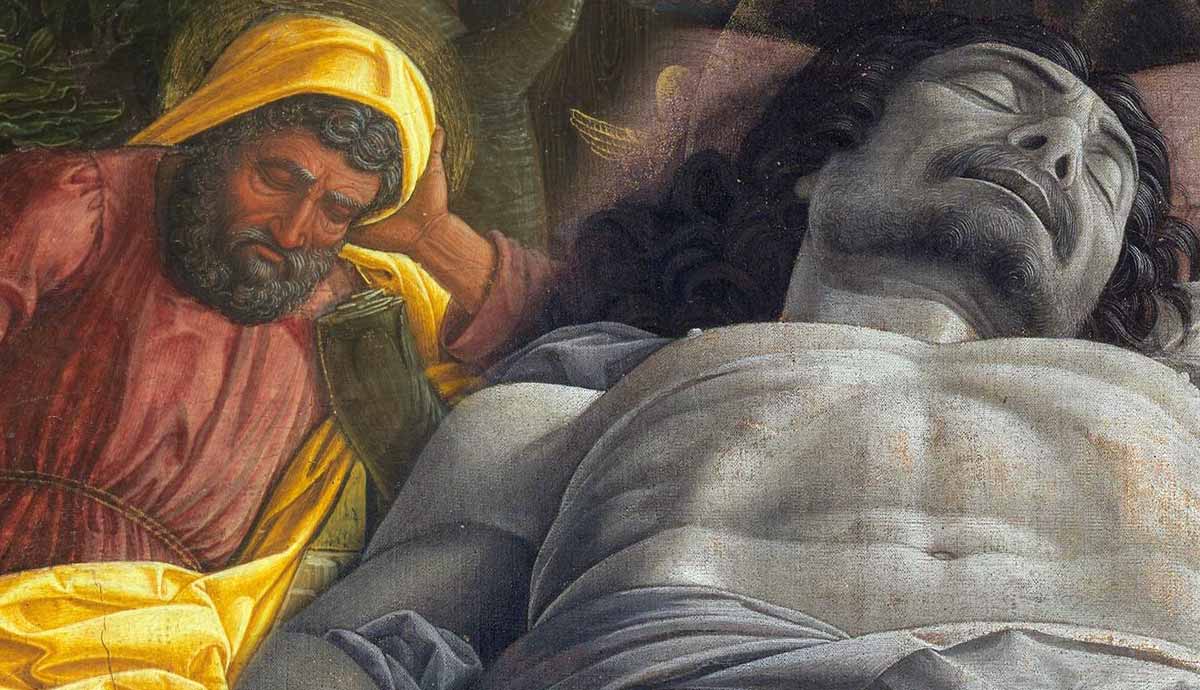

5. Lamentation of Christ: Andrea Mantegna’s Most Famous Work

Lamentation of Christ demonstrated his remarkable and almost provocative approach to perspective and composition. The dead body of Jesus Christ, just removed from the cross, is positioned with his feet towards the viewer as if they are standing next to the figure. Still, the feet do not take up the space required by the usual application of perspective. Instead, Mantegna shortened the Savior’s body in a way that created the illusion of space and depth without distorting the figure into a caricature.

The exact date of the painting’s creation remains unclear, as it was discovered in the artist’s studio only after he died. He painted it specifically for the decoration of his tomb. However, Mantegna’s sons sold the painting to pay their debts, and now it is part of the Pinacoteca di Brera collection in Milan.